|

||||||||||

|

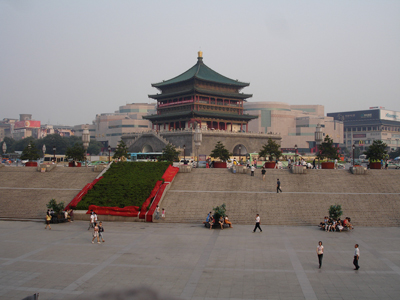

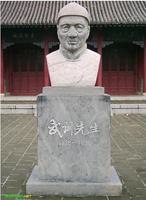

ARTICLESThe Han SupremacistSang Ye interviews Zhai Quan'anTranslated by Geremie R. BarméWe include this chapter from The Rings of Beijing: China's Global Aura by Sang Ye and Geremie R. Barmé by way of expanding our discussion of Critical Han Studies, featured in New Scholarship in the September 2009 Issue No. 19. While this oral history interview is at a considerable remove from the measured tone of Critical Han Studies, its nonetheless offers a contemporary vernacular intervention on the subject. Zhai Quan'an is a 42-year-old man from Xi'an, the provincial capital of Shaanxi. He is an unemployed worker and self-styled avant-garde thinker. After encountering him outside Beijing Normal University, Sang Ye arranged to interview him on the eve of the August 2008 Beijing Olympics for our book The Rings of Beijing. Although Zhai is convinced that his activities as a promoter of 'Han culture' and compulsory education had brought him into conflict with the authorities, it should be noted that the process of 'cleaning up the capital' (jinghua shoudu 净化首都), that is, ridding the city of the indigent, floating population began before he began his quest to revive the supposedly flagging fortunes of China's native culture. In Zhai's view the vital essence of China has been depleted from the time of the Tang dynasty over one thousand years ago. Intriguingly, he appears to be unaware that many elements of the Tang achievement were related to cultures and peoples originating far from the narrow area known as the Central Plains (Zhongyuan 中原). Nonetheless, his encounters with China's 'harmonious society', his clashes with the police and experiences with extra-judicial incarceration (the 'black jails'), not to mention a mental hospital, are deeply disturbing. With an eye on China's historical past, and mindful of the reputation of the Qing-dynasty beggar Wu Xun, Zhai Quan'an is perhaps thinking of his own place in history. I would like to thank Linda Jaivin for her careful reading of the original and draft translation and her numerous helpful (and elegant) suggestions.—The Editor I'm a member of the vanguard of advocates for compulsory education and the promotion of Han culture. I'm also a beggar from the provinces who has infiltrated the capital. If I was just a beggar, the police would relax. At most I'd be a blot on the landscape, and they're not too energetic when it comes to looking after the city's image. But the police aren't stupid. They can tell immediately that I'm a beggar with a difference. They see that I'm unhappy about the state of compulsory education; I talk about it wherever I go. They also know that I'm an active promoter of Han culture, a flag-waving, slogan-chanting avant-garde. People who are ahead of their time can be pretty annoying. They'd prefer to 'harmonise' us out of existence.[1] They can't afford to wait around until lots of people have rallied to my cause. By then it would be far too inconvenient to take me out. It's easier for them to claim that they're just 'ridding the city of beggars'. That's the pretext they've used to detain me many times already.  Fig. 1 ‘Backbone of the Nation’, decorative wall at the Great Goose Pagoda 大雁塔, Xi’an, Shaanxi province. Photo: GRB. I do what I do because of the situation in China today. Like it says in the national anthem, 'The Chinese nation is facing its greatest peril',[2] though perhaps you could say that the Chinese nation is confronted with its greatest peril once again. That's why I put these signs on my bike that read 'Han people! Your mother is dangerously ill! Return home immediately!' and why I write on my clothes, 'Take action to enforce the implementation of the Compulsory Education Law'. That's what I'm calling for, and it's precisely these issues that are our most pressing task today because our country and our people are in grave danger. The people of China today have no culture. There are countless reasons for this, but the most fundamental is the loss of Han culture. The majestic Han culture that nurtured our people in the past has been consigned to oblivion; it no longer exists. This is the root cause of all our problems. The Han culture I'm talking about is not just about the Chinese script (Han zi 汉字) or language (Han yu 汉语). It is the culture that was decocted and refined for a long time before finding form and spirit in the Han dynasty [206BCE–220CE] and by all rights ought to have been transmitted down through to the present day. During the Han Dynasty, China and the Chinese people were a global power. Foreigners came from all directions to pay homage to the Han; the whole world courted us for our learning. We had 'hard power': 'whoever encroached upon the powerful Han would be annihilated'.[3] If people didn't submit we'd wipe them out. We also had even more persuasive and influential 'soft power'. In those days the Huihui of the Western Regions[4]—the place that today is the home base of terrorism—had no choice but to accept our value system. Even White People—accustomed then as now to lording it over others—were assimilated into obedience. That's a concrete expression of Han greatness. Around 30BCE, the Great Han attacked Kangju 康居[5] and inflicted a massive defeat on the king, or Shanyu, of the Huihui, along with over 100,000 Roman soldiers he'd hired to make trouble for us. After killing the king, the outstanding Han general Chen Tang 陈汤 resettled the Roman prisoners of war and others who had surrendered in the Hexi Corridor [in modern-day Gansu province]. After years of spent tilling the soil out there undergoing labour reform these people became known as the Lushui Barbarians (Lushui Hu 卢水胡) and they're still living there. Isn't that an example [of the power of Han]?  Fig. 2 The Great Goose Pagoda and rebuilt ‘Tang-style’ museum buildings. Photo: GRB. The Tang dynasty [618-907CE] wasn't too shabby either. But nothing has had the same luster since. Over time, the essence of the Han has dissipated; our very marrow has become progressively weaker, and we've concerned ourselves more and more with mere appearances. In the process of fixating on superficial things we've lost our essential dignity. That's why sometimes we find ourselves either in a murderous frenzy ourselves or are the victims of it. Whether killing or being killed, neither the Chinese nation nor people can make sense of how we've come to such a sorry state. We just muddle along. After getting by in this fashion for over a thousand years, we find nothing left of Han culture in China at all. And the main ethnic group within China—the Han—have degenerated so far that we don't even know what morality, humanity or righteousness are any more. Laozi 老子 was the first teacher in Chinese history; there were no others before him. He was even the mentor of Confucius. The very concept of 'teacher' (老师 laoshi) is built on the foundations he laid down as the father of Han culture. We Han have our own Bible: it is Laozi's Daode Jing 道德经. As it says, '…when the Way is lost Virtue remains; when Virtue declines there is Benevolence; when Benevolence disappears there is Righteousness, after that all that survives is Ritual Propriety. With the decline of Ritual what remains is but a weak sense of Loyalty and Sincerity and hence strife is born.' Herein lies the basic meaning and significance of dao 道, or the Way. The Daode Jing predicts the kind of decline a nation and a people will experience after the Way is lost. Why is it that the Japanese and Koreans were not fearful of Western culture during their process of modernization whilst it absolutely terrifies us? It's because these little countries imported Han culture when we still had the Way, and indeed, Virtue, and maintained its essence. So, although they are small, they are very strong and confident. As for us, we've been on a downward trajectory ever since we lost the Way, Virtue, Benevolence, Righteousness and Ritual as well. We have declined so far that we have hit rock bottom, to the extent that our 'rituals have collapsed and our [courtly] music is defunct' (li beng yue huai 礼崩乐坏). We've fallen into a filthy ditch, reduced to weak-willed and feeble carcasses without the strength to tie up a chicken. We are spineless and utterly without armour. Our defenses could be breached with a toothpick. No wonder we're frightened of everyone. You heard about that female professor they call Yu Dan 于丹, you know the one whose appeared out of nowhere? She's always on television talking about Confucius, but her version of Confucianism is limited to ritual; it boils down to social order and harmony. It's just the sort of crap that old women with too much time on their hands like to come up with. Because Yu Dan's a professor at Beijing Normal University, I've been coming here every day to wait for her at the campus gate. I'm determined to debate her on her own turf and use the opportunity to promote Han culture. I'm talking about the essence of the culture, she's on about the fringes, and even there she gets it wrong. The way she talks about Confucius' Analects 论语, it's as though they are but footnotes to her own ideas. And she's just a footnote to the [present political dogma of the] harmonious society. She's even more wretched than a beggar.  Fig. 3 Central Xi’an. Photo: GRB. Once you've lost the Way, Virtue, Benevolence and Righteousness you have no choice but to emphasize Ritual. What I mean by that is that once the Loyalty the people have towards the state has been so diluted that it's completely flavourless, and the state has lost all trust in the people, then you have no choice but to talk about Ritual. Ritual is the last line of defence. When there is no social order or real harmony then the authorities talk about ritual because they don't have anything left in their arsenal. There's no way that Professor Yu Dan doesn't know that; she can't pretend she doesn't understand that this is the essence of Ritual, though she dresses it up differently in her lectures. I'm being kind when I say she's even more lowly than a beggar. The English and French translation of Putonghua 普通话 is 'mandarin'. Mandarin is the phonetic transcription of 'Man Daren' (满大人, 'Manchu official'). The Putonghua ['Standard Chinese'] of today was the official language of the Manchu bureaucracy during the Qing dynasty. This begs the question: is Putonghua really the 'Chinese language' (Hanyu), the language [yu] of the Han Chinese [Han]? I can tell you unequivocally that it is not. The real language of the Han Chinese is my native dialect, the language of Xi'an 西安. True Chinese is the language spoken in the Han and Tang dynasties in their capital Chang'an 长安 [present-day Xi'an]. Chang'an speech was not only the dominant language of China, it was the dominant language of the world as well: whether it was the Huihui of the Western Regions or the Jap Devils sent as ambassadors to the Tang court, if they came to get the Buddhist scriptures from us they had to speak the language of Chang'an. Many lines in Yuefu 乐府[6] or Tang poems don't sound right if you recite them in modern Standard Chinese; they don't rhyme. But if you read them in the language of Chang'an, the rhyme scheme works perfectly. Chang'an dialect is true Chinese: the proof is in the poetry. Our Han culture assimilated Japan-Korea-Vietnam-Singapore-Malaya-and-Thailand. To put it a bit more politely, we influenced these small places that eventually came into being as nations in their own right. But we ourselves were enslaved by the Mandarins; we ended up speaking slippery and insincere Mandarin. Even worse, we abandoned Chang'an, a perfectly decent capital. It is a national tragedy that our ancestors thought they could ensure long-lasting peace and stability by building their capital cities in Nanjing and Beijing. Han culture is extremely complex, and its content can't be encapsulated in a mere sentence or two. To put it in the simplest terms, Han culture expresses itself in two very distinct ways: The first is magnanimity and a tolerance of diversity. It is not fearful of the incursions of other cultures. It has a strong stomach capable of digesting you, sucking out the nourishment and shitting out the dross. We display magnanimity and tolerance because we have grasped the Way. It's not a manifestation of that kind of Benevolence that comes from having lost the Way, because once you've lost the Way, Benevolence is but evidence of helplessness. When people talk about instituting a government of benevolence (renzheng 仁政) they're just pretending they don't know how bad things are. The second essence of Han culture is having the guts to annihilate those who offend the Mighty Han. If some bastard really interferes in our business, we'll wipe them out no matter how far away they might be. This spirit of daring to struggle and daring to succeed is possible when the Way is with us. As long as we abide by the Way it doesn't matter if say we don't have Virtue, or Benevolence. We'll attack you and there's nothing you can do about it. If the Way is with us, the Great Righteousness is on our side. Our Ritual Propriety is outward looking; if I attack you it's for the sake of maintaining good world order.  Fig. 4 Statue of Yang Guifei 杨贵妃 at Huaqing Pool 华清池 outside Xi’an. Photo: GRB. Ha! Putting it like that makes it sound similar to the behaviour of American Imperialism, doesn't it?! But the core values of Han culture are different from those of the West. American Imperialism is by its very nature bad; it is an Evil Tyrant bereft of the Way, Virtue, Humanity and Righteousness. It's only because we've lost the Way that they got their chance and have become such a strong power. Following the Han and Tang dynasties, these two outstanding manifestations of Han culture faded away. Apart from being invaded by others, ending up as the slaves of the Mongol-Yuan dynasty and the Manchu-Qing dynasty, we spent the rest of the time fencing ourselves in and killing each other. We muddled along in constant fear. When we couldn't get away with that any more, we made revolution. Before the revolution we were poor, ignorant and weak and that's why we made revolution. But following the success of the revolution we freed ourselves (fanshen 翻身) only to find we were still poor, ignorant and weak. In the end all the promises made by emperors, presidents and chairmen have proved to be 'phony, bombastic and vacuous' (jia da kong 假大空). This is why I needed to take action and become a promoter of compulsory education and Han culture. I bought this broken-down old bike for 38 yuan, tied a couple of little flags with slogans on them to the bike and built myself a donation box. There was so much I wanted to say that I wrote slogans on my own clothing as well. I'm doing everything in my power to wake up society from its slumbers. I set out from Xi'an with 400 yuan in my pocket. My route took me via Weinan and Huayin before I entered Henan province from Tongguan. I didn't beg when I was travelling through Luoyang, Zhengzhou and Xinxiang, only after getting to Hebei province and [the provincial capital] Shijiazhuang. By then I only had 30 yuan left, definitely not enough to see me through to Beijing. I started begging for food. In Baoding I met a teacher by the name of Zhang who donated 110 yuan and took me to a bookstore to buy me a copy of the Compulsory Education Law.[7] The righteous support of Teacher Zhang misled me into thinking that it wouldn't be that hard for me to support my propaganda work through begging. I never thought that his donation of 110 yuan was the most I'd ever get in one go. No one's broken that record to date. I arrived in Beijing on the eve of Chinese New Year [in 2008]. It was late at night and I stood in front of Tiananmen thinking of the hunger and cold I'd endured on my 2500 kilometre trek. I was uplifted by the realization that I'd actually survived the most difficult phase of my journey. Now, I thought to myself, I can finally set to work. Of course, I was wrong again. Since arriving in Beijing, things have got harder and harder. My best days are behind me. Back in Xi'an I was unemployed and living on social security. After high school I worked in a textile print factory while doing a university course at night. Even after I got my degree, I remained at the factory. In 1997, the factory went through a merger and I was made redundant. They gave me a 7000-yuan pay-out. I made a new career for myself in construction, but following a lawsuit related to a demolition job, I went bankrupt. After that I worked as a car park attendant, but the wages were low and the hours long, so after a while I quit that and opened a small shop. Taxes were so high you had to cook the books to make a profit, but I'm not into that sort of monkey business so it didn't work out and I was forced to close the shop in 2007. By then I'd lost confidence in myself and my health wasn't very good either. After surviving on social security for a while I decided to take my 400 yuan and set out on my mission to promote compulsory education and Han culture. I felt that my life had no meaning otherwise. I needed a change; I had to take action. I thought I should take some responsibility and do something meaningful for the country and our people. Having reached a dead end in my life, I found a mission as a member of the advance guard, riding my bike and promoting my causes.  Fig. 5 Poster for a song-and-dance version of ‘The Song of Everlasting Regret’ (Changhen ge 长恨歌) the classical poem by the Tang writer Bo Juyi 白居易. Photo: GRB. If you want to promote Han culture you have to be concerned about compulsory education. Shortly before I set out from Xi'an a teacher at the No. 2 Middle School in Qinyuan County, Shanxi province took some students jogging on the highway and they were hit by a large truck carrying coal. Twenty-one students died and more than thirty were injured. The accident happened because the driver was sleepy, but the teacher should take some responsibility too. He shouldn't have to take his class out on the highway. Yet where else could they exercise? There are primary and high schools throughout the country that have no sports fields, not even the most rudimentary of yards. It's been like this for years and no one's done anything about it. Even worse, those schools are far from fulfilling the standards for free education set out in the Compulsory Education Law. Only something like 70% of children in China attend the first years of high school. That figure is far too low, and the statistics are skewed upwards because they include figures from urban areas. In the countryside the figure is under 50%. That means that over half the kids in China's countryside have never been inside a high school. Their schooling ends when they finish their sixth year of primary school, if they even get that far. According to law they are entitled to free education, but it simply doesn't happen. The Compulsory Education Law was promulgated over twenty years ago. It clearly stipulates that, 'The state shall institute a system of nine-year compulsory education: 'Compulsory free education is a unified national policy pertaining to all children and youth of the appropriate age. Young people must receive an education: this is a public enterprise for which the state must be responsible. Compulsory free education means education free of fees of all sorts'.[8] But the reality is very different. For over two decades the state has failed in its duty of care and its undertakings: they've given us a promissory note. In reality only Jiangsu province has compulsory education; other provinces have only achieved it in some localities. Of course, local governments that don't provide free compulsory education are breaking the law. But no one is standing up to protest. Over these past twenty years no one has ever taken them to court for failing to carry out the Compulsory Education Law. No one has demanded that the government honour the promise that they have made to the people. China is going against the international trend. Over 170 countries worldwide provide their children with twelve years compulsory education. But China, a member of the UN Security Council, fails to do so. China only specifies nine years of compulsory education, and even that goal has not been realized nationwide. Access to education is a basic human right; the state has a responsibility to provide schooling. The lack of education blocks the advancement of common people up the social ladder and perpetuates the inheritance of poverty, ignorance and weakness. As a result the poor lose hope. Our nation and people are confronted with a grave danger from which there is no escape, and no way forward either. Another crucial issue is what is happening with the compulsory education that is available—and the related problem of the limited resources for vocational training and higher education. In order to guarantee an equitable distribution of resources, there has to be a system of examinations. But the examination system for access to higher education that's currently in place concentrates the focus of all education on passing these exams. Kids in middle school[9] have to pass exams to get into high school. If you don't make it into a decent high school, then forget about leaping over the next obstacle and getting into university. So teachers must start training students for the senior high school exams from the moment they enter middle school; the exams become the main focus of education. Compulsory education thus becomes a form of 'exam education', a new kind of tutoring school that mirrors the system of the old days.[10] Because of this, the system has created a modern version of the imperial exam (keju 科举). As for the provision in the law about schools not charging academic or other fees, that's yet another empty promise. You can't even find a school that doesn't charge fees. So they can't charge for tuition—if you don't hand over 'sponsorship fees', 'materials fees', 'fees for extracurricular activities' and all the rest you can't even get in the door. Charging fees—for all manner of ridiculous things—and focusing education on the passing of exams: that's the reality of compulsory free education today, compulsory free education with Chinese characteristics. People here in the capital treat me with suspicion. That's despite the fact that I've got this plaque around my neck with the Compulsory Education Law and my ID and regardless of the placards on my bike advocating compulsory education and the promotion of Han culture. Some people stand and stare, some shoo me away and others look straight through me. Others say that I must have water on the brain, and there are even those who want to beat me up. My impression is that the majority of young people in Beijing are desensitized, as though for 'middle class' or 'rich people' like themselves compulsory free education means nothing. The older people are even more wary: they say these days even the beggars have new techniques. They say I'm a grifter. Some things people say are pretty funny. One person remarked that I'm begging to get enough money to buy cabbage but worry about the trade in crack (nazhe mai baicaide qian caoxin mai baifende shi 拿着买白菜的钱操心卖白粉的事). Is universal education really irrelevant to the middle class and the rich? They've forgotten that 'The ashes in the pit were not yet cold when rebellion rose in the east;/ Liu Bang and Xiang Yu were hardly men of letters.'[11] They've forgotten that after he achieved power the uneducated [Emperor] Liu Bang 刘邦 ordered the people to study as a means of achieving long lasting peace and stability. He told them that if you want to advance yourself, you have to study. But then again, maybe it's not a matter of forgetting all this: maybe these people never understood Han culture in the first place. Since I've been in Beijing, I've received donations totaling over 1000 yuan. A reporter interviewed me not long ago and asked how much I'd collected in all. He wrote me up in his paper as being this guy who'd collected over 1000 yuan by working the streets, but he said that I hadn't spent a cent of it on compulsory education itself. It had all gone into my own pocket for my living expenses. The same journalist checked with a legal firm and they told him that donations for causes such as compulsory education should be made through [registered] charities or via the educational authorities. It's fraudulent to collect money for a cause and not put it through the appropriate channels. So I really can't deny that I'm a beggar. I'm begging out of financial difficulty. If I don't say that I could get in trouble with the law. I'd have to admit my guilt and accept the consequences.  Fig. 6 Former Party General Secretary Jiang Zemin encouraging the use of cultural heritage for patriotic purposes. Poster from Famen Temple 法门寺, west of Xi’an. Photo: GRB. I conduct most of my propaganda work at the Ministry of Education and various universities. None of them will let me through the front door, so I have to work the gates. Public Security has detained me five times. They've handcuffed me and, once, they even threw me into a mental asylum. The first time I was detained was in the vicinity of the Ministry of Education. The police stopped me on the road before I even made it to the entrance. They ordered me to accompany them to the police station. I refused, saying I hadn't broken any laws, why did I have to go with them? They called for backup and dragged me off to the station. After taking my photo, they ignored me for a few hours before suddenly leading me into a room to make a statement. I was just explaining myself to the policeman who was recording my statement when another particularly fierce one came into the room. He pointed at me and started shouting, 'That's rubbish, you cheat! You're just pretending to promote education and culture in order to scam money!' I gave him tit for tat: 'You're twisting the facts. You're the cheat!' He jerked my arms behind my back and handcuffed me. I was left there for about half an hour before a more senior officer came in. He ordered them to take the cuffs off and instructed me to sign the statement I'd given and put down a fingerprint. Then they let me go. After that they changed tactics. When they took me in the next time I wasn't accused of a scam. First they tore up my placards, then broke my flags, then confiscated the clothes on which I'd written my slogans and finally they said that since I was a beggar they'd send me to the reception centre for beggars and let them look after me. Those centres are there to help the indigent; they have no right to restrict your personal freedom. I rested up a bit and then discharged myself. Once again the [police] changed their modus operandi. The next time they took me to the centre they said that I wasn't right in the head and got them to send me to a mental hospital. I was in there for forty-two days until my brother came to get me out. I was medicated the whole time. I was surrounded by screaming patients; it nearly drove me crazy myself. By the time I got out I was very weak and my stomach had shrunk. I stayed in bed in a hostel recuperating for a whole month. I tried suing the mental hospital for illegal detention but no court would accept the case, nor could I find a lawyer willing to take it on. There is no future for China unless we institute compulsory free education. The failure of our education system equals the failure of the Chinese people. The reason that our education system is in this state is due to the eradication of Han culture. We are directionless; we don't even recognize the foundations [of our culture]. Such a failed education system is an obstacle to the enrichment of Han culture. Since I've thrown myself into this cause I have no choice but to pursue my dream. Although I suffer the derision of the ignorant and the attacks of the powers that be, I have no choice. Fortunately for an avant-garde like me, there are others who have gone before me. There was Wu Xun 武训 at least.[12] People took advantage of him because he was illiterate so he decided to beg for money to set up schools. After working for decades he finally had enough money to establish three schools. Of course, Wu Xun only set up schools, and because of that he didn't come into direct conflict with the culture of the Manchus; they praised him and honoured him with commemorative archways and wrote up his life story in the history books.  Fig. 7 Commemorative bust of Wu Xun. My situation is certainly different; I want to promote compulsory education as well as Han culture. By putting the two things together it would seem as if I'm not interested in building schools so much as tearing down the temple—as if the creation of schools was just a cover for my true goal. But in that case I need to mention another precedent—that of Mao Zedong. In the interview he gave to Edgar Snow in Yan'an [in 1936] he said that the reason that a farmer's son like him could get a tertiary education was because of the policies [in the early Republic] that supported free education for students at teachers colleges. But after Mao overturned the system by which the Chinese were kept poor, ignorant and weak, and his announcement in Beijing that 'henceforth the Chinese people have stood up', he failed to fulfil his responsibility to introduce universal compulsory education. He can never be washed clean of this shame. But for all that, he's also left us with a heritage: he led us in singing the 'Internationale' which includes the line, 'There are no supreme saviours/ Neither God, nor Caesar, nor tribune./ Producers engaged in production, let us save ourselves.'[13] I don't know whether Wu Xun believed in gods or spirits, but I do know he had faith in the emperor. What I believe is that [as it says in the 'Internationale] 'if we are to create happiness for humankind, we need to rely on ourselves.' So it's no surprise that I've encountered so many difficulties. I'm more radical than Wu Xun. To revive Han culture we don't need to tear down the temples. My enemies are everyone's enemies. They are the enemies that our nation and our people all face: poverty, ignorance and weakness, as well as all that is 'phony, bombastic and vacuous'. Notes:[1] 'To harmonise' or hexie 和谐 is used as a verb to indicate the suppression, censorship or elision of unsettling, untoward or uncomfortable ideas, people, expressions and actions in contemporary China. The term has gained this new meaning, and usage, as a result of the 'harmonious society' promoted by the Party-state led by Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao. [2] The original reads, Zhonghua minzu daole zui weixiande shihou 中华民族到了最危险的时候. The Chinese national anthem is the wartime song 'March of the Volunteers' (Yiyongjun jinxingqu 义勇军进行曲), written by Tian Han 田汉 with music by Nie Er 聂耳. [3] fan qiang Han zhe sui yuan bi zhu 犯强汉者虽远必诛, the original being 明犯强汉者,虽远必诛. This is a well-known line from the biography of Chen Tang, a general in the Western Han (see below). It comes from a memorial Chen wrote to the Han emperor. [4] A generic term dating from the Tang period for peoples from Islamic countries, as well as for Islam itself. Zhai's use is anachronistic, not to mention pejorative. [5] A powerful kingdom around the area known as Sogdiana northwest of modern-day India. [6] 乐府, literally 'Music Bureau', is a generic term for ballads that were recorded and codified as Music-Bureau (Yuefu) Poems from the Han dynasty. Early yuefu include sacrificial music, songs of the nobility as well as narrative folksongs. [7] The original law became effective on 1 July 1986 and was replaced by a new law promulgated in 2006. For details, see http://www.gov.cn/flfg/2006-06/30/content_323302.htm. [8] Here Zhai is quoting the Second Article in the 2008 law: 义务教育是国家统一实施的所有适龄儿童、少年必须接受的教育,是国家必须予以保障的公益性事业。实施义务教育,不收学费、杂费. [9] The equivalent of years seven to nine, or junior high school in the US system.

[10] 县学乡塾. Traditionally, children were trained at local schools in the Confucian classics for the sake of passing local, provincial and then the highest-level imperial exams. [11] In Chinese, keng hui wei leng shandong luan, Liu Xiang yuanlai bu du shu 坑灰未冷山东乱, 刘项原来不读书. This is a line from the eighth-century Tang poet Zhang Jie 章碣 about how the uneducated can lead rebellions. Mao Zedong quoted Zhang's poem a number of times in his political career. [12] Wu Xun (1838-96) was a late-Qing era beggar who collected money and built schools for the dispossessed. Celebrated in both the late-Qing and Republican eras he was denounced in the early years of the People's Republic along with a bio-pic starring Zhao Dan 赵旦 entitled Life of Wu Xun (Wu Xun zhuan 武训传) during the socialization of the education system. His reputation was partially restored in the mid 1980s although the film about his life is still not widely available. [13] From the French original, 'Il n'est pas de sauveurs suprêmes/ Ni Dieu, ni César, ni tribun/ Producteurs, sauvons-nous nous-mêmes.' |