FEATURES

The China Critic - 1939 | China Heritage Quarterly

The China Critic: a Chronology

William Sima

Australian Centre on China in the World

William Sima, whose research into the history and contents of The China Critic led to this combined issue of China Heritage Quarterly, has created a Chronology of the weekly. It follows the progress of The Critic from its first appearance in May 1928 through the highs and lows of the 'Nanjing Decade', and then through its various wartime permutations.

Will's Chronology, which is arranged by year below, accounts for the changing fate, and the friable editorial stance, of The Critic. It also provides numerous links to the articles under discussion allowing for them to be appreciated in an historical context.—The Editor

1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | 1936 | 1937 | 1938 | 1939 | 1940 | 1945

1939

9 February

Fig.1 A China Press advertisement for the popular 'Charlie Chan' comic strip, 16 February

George Kao 高克毅, who would achieve fame in later life as a translator and promoter of Chinese classics in the English-speaking world, contributes 'China Relief' this week: 'a new term I am trying to introduce—"China Relief", more or less like "comedy relief", in the realm of literature an the arts.' Kao explains 'China Relief' as being a feature in Western literature and the arts, from De Quincey's writing on opium addiction, to Somerset Maugham's On a Chinese Screen and the recent Hollywood films like Shanghai Express and The China Clipper, where the presence of the term 'China' or 'Chinese' serves to lend works a certain mystique:

I must say I am by no means well informed on the subject, nor could I lay any claim to its discovery, else I should be producing a dissertation on 'Orientalism in Western Literature,' or some such august title. But an hour or two of browsing everyday and a weekly movie leave me with the impression that there Americans are today probably the most adept in the use of 'China relief'—as I have come to term it—as a kind of technique to achieve rhetorical, literary or dramatic effect.

30 March

The Editorial 'Seven Deadly Sins' this week commentsupon Resurgam, a recently published collection of essays by Madame Chiang Kai-shek, in which she proposed seven evils which continue to retard China's growth: self-seeking, face, cliquism, defeatism, inaccuracy, lack of self-discipline and evasion of responsibility. The writer of this editorial agrees with what Madame Chiang identifies as being the source of these 'sins':

She sees them for exactly what they are, namely, as an outgrowth of the period of corruption through which China passed as a result of the many decades of Manchu rule, and not as fundamental characteristic of the race which are ineradicable and impossible to change.

The writer compares Resurgamwith Lin Yutang's My Country and My People, which also contained criticism of the 'Chinese character.' While Lin's representation of Chinese weakness received criticism from 'a certain sensitive and less self-honest section of the public in China', the writer hopes that Madame Chiang's 'taking up the cause' will lead to real improvement in the Chinese character:

[that] Madame Chiang herself is taking up the cause and is preparing to actually initiate action to eradicate these evil sores from Chinese life should more than compensate any misgivings Dr. Lin may have had in the past with regard to his ideas of a rejuvenated China ever taking shape.'

27 April

The editorial 'Spiritual Mobilization' describes the official inauguration of this new movement:

An impressive ceremony was witnessed in Chungking on April 17 when Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek launched the 'Spiritual Mobilization Movement' by taking his oath to observe the 'citizen's commandments' reads this week's headline editorial.

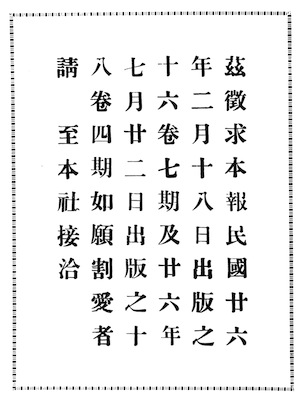

Fig.2 The China Critic requests readers to submit missing back issues, 27 April 27

Also in this issue, 'The Flag Incident' reports on a 'series of regrettable incidents in the French Concession', in which French police ordered the lowering of Chinese flags within the precincts of the concession. The flags had been raised by 'patriotic citizens' to commemorate the launch of Chiang's Spiritual Mobilization:

There is a close identity of interests between China and France in the present conflict and it would be most regrettable if such incidents as recently occurred should be allowed to mar the close co-operation which so happily exists between the two countries.

C.T. Wang 王正廷, in his special article 'Why China Will Win the War' (originally printed in a Chinese newspaper and translated by H.N. Ning), proposes four historical precedents in which underdogs have emerged victorious in war—The American War of Independence, the defeat of Napoleon, the American Civil War and the defeat of Germany in the Great War—as reasons why China will defeat Japan. Aside from China's vastly larger population and endowment of natural resources, Wang considers'The Chinese National Spirit' to be an important factor:

Though the people have suffered enormous losses: their families broken up, their houses destroyed, they have never denounced their government … China is fighting not only her own battle, but that of all those countries interested in the Far East. Lord Strabolgi said, 'The Chinese are fighting our battles.' This is a true statement, and if the whole of the Chinese people remain united and support Generalissimo Chiang, the victory will without doubt be China's!

11 May

In 'Pearl Buck's First Nobel Effort', George Kao reviews The Patriot, the first novel released by Buck since claiming the Nobel Prize for Literature the previous year. He writes that the novel will likely receive a better reception in China that in the US: 'it is impossible for a Chinese reader not to catch the author's many details of description and character sketch'; 'the American reader quite naturally will look for satisfaction in Mrs. Buck's chief characters, and here many have expressed mild discontent.' But Kao believes Buck's attention to setting rather than character is where this novel's strength lies:

Reading 'The Patriot' is like reading for the first time some famous novel the movie version of which you have already seen… . Since Mrs. Buck's novel is living and pulsating China, lifted with thin fictionalized disguise out of current history, we would tend to look for any possible real-life persons after whom the author may have modeled her characters.

8 June

The editorial 'The Anti-British Movement' reports on recent Japanese attempts to incite anti-British sentiment in China, mentioning statements made in Japanese-controlled media and recent Japanese encouragement of worker's strikes, and anti-British activities in various cities across the country. 'The reason for the Japanese attitude is a simple one', contends the writer: 'Japan has definite ambitions in certain regions of China, where British interests dominate. Japan can only fulfil these ambitions by driving the British out.'

Despite Japan's efforts, this writer notes that Chinese sentiment in Shanghai, both within the foreign settlements and in areas under National government administration, 'is decidedly friendly towards Great Britain'. He cites the decision of 'public bodies in Shanghai' not to mark the 30 May memorial day (commemorating the 1925 massacre of Chinese workers by British-led troops in Shanghai) as an 'indication of the pro-British feeling of the population.'

29 June

'Geneva's Bibliotheque Sino-Internationale', a contributed article that appears to have been written by a representative of the Sino-International Library in Geneva, provides a brief history of this library since its founding in 1933, a summary of those who were involved with its establishment and its current activities:

The institute does not limit its activity, great as it may be, to the cultural domain. It constitutes also the most important centre of propaganda for China in Europe. It was already to in times of peace, for it had made itself the centre of social gatherings, where Chinese and distinguished Westerners, formed and kept up friendly relations and where, thanks to such personal contact, cultured Occidentals were enabled to realized what the Chinese really were and what they want.

With so much discussion in The China Critic this year of the need for effective propaganda overseas, the writer of this article lauds the efforts of the Library in promoting China's interests in Europe:

By sending regular 'communiqués' to the foreign press it renders Japanese defamations ineffectual, informs the public regarding the progress of our heroic fight as well as the atrocities committed by our enemies. The most distinguished Chinese patriots, including M. Wellington Koo [顧維鈞], our ambassador at Paris, have proclaimed aloud the usefulness of its activity.

20 July

This week's issue contains two articles that consider the differences between the Chinese and the Japanese. T.D. Gen's 耿廷楨 'A Glimpse of the Japanese Mind' comes with an editorial disclaimer that says that although it 'deals with the Japanese view before the outbreak of the present war, [it] may serve to reveal the fundamental attitude of the Japanese toward China.' Gen recounts his attendance at an event organized by the Nippon Cultural Federation (held sometime before the war, though no precise date is given), and includes questions that were asked at a press conference after the event.

In another essay an unnamed 'Reflector', who reveals that he is a Westerner, describes 'Mental Differences Between Chinese and Japanese':

What strikes the eye of the Westerner, however, are the basic differences both physical and mental between the two now opposing sides, which, although they both belong to the yellow race, are more marked than any two variations of the white race, the Englishman and the Spaniard, for example, or the square-headed German or the olive-tinted Italian.

This writer goes on to argue how such differences manifest in social and political life: 'Nipponese teamwork' and 'Chinese individualism' are seen as being a decisive feature of the current conflict; 'the Chinese faculty for ingenuity' was responsible for the inventions of printing and gunpowder, while the Japanese proclivity for imitation allowed them to '[select] the best the world had to offer' in military technology and organization, giving the Japanese empire, or Dai Nippon, 'an advantage over the Chinese in warfare right from the start.'

17 August

The Editorial 'Anti-Foreignism Spreads' describes developments in Japan's anti-British campaign since the article of 8 June: 'While at first the anti-foreign campaign was directed solely against the British, on the excuse that Great Britain was "aiding Chiang Kai-shek", it is now being directed against the Western powers more generally.' The writer makes it clear that this Japanese campaign intends only to remove other foreign powers as they establish a 'new order' of 'monopolistic control' over China, and to '[divert] attention from the desperate plight of their armies', now bogged down in a costly war. While noting that 'there seems little inclination on the part of the Chinese population as a whole' to support the Japanese, he forecasts that this movement might eventually spell the end of foreign presence in China:

Nothing is more likely to stimulate the anti-foreign campaign so much as the knowledge that the western nations can be bullied by Japan… . Whatever happens, it is clear that the foreign powers will stand or fall together in the Far East. Indeed, neither the United States nor France, nor, for that matter, Germany or Italy, can afford to stand aloof from Great Britain as she confronts Japan today… . There are only two alternatives facing the foreign powers today, either to take united action to enforce respect for their treaty rights or to be prepared to see them trampled underfoot and completely wiped out by Japan.

14 September

Eleven days after Britain and France declare war on Germany, the Editorial 'September 18' acknowledges that Europe 'is today locked in a deadly war, that is likely to spread like a conflagration and envelop the entire world'. It also criticizes Europe for having neglected China's plight for the last eight years. The author is especially critical of the British Foreign Secretary, Sir John Simon, one of the leading advocates of appeasement whose 'indifference to the fate of that remote Chinese province [Manchuria] is costing Great Britain today millions of pounds sterling for the provision of arms, munitions and all the necessities for the conduct of a modern war.' For those at The China Critic, the start of the war is old news:

Where it will lead, no one knows. When and where it will end, is even less predictable. But one thing we can say for certain and, that is, that it started neither on September 1, 1939, when Germany invaded Poland, nor two days later when Great Britain and France declared war on Germany, but on September 18, 1931, when Japan first embarked on a course of international lawlessness and brigandage, since when the world has ceased to live in peace.

19 October

'According to Mr. Ku Hung-ming [辜鴻銘], the characteristic of the Chinese character and Chinese civilization are three in number: depth (沈潛), broadness (遠見) and simplicity (諄[淳]樸 )', writes Y.S. Chao 周蓉生 in 'A Religion of Good Citizenship'. This essay explains the Confucian principals of Ku Hung-ming, a Malaysian scholar of the late Qing who advocated the preservation of the monarchy, and proposes that they are still relevant for China today.

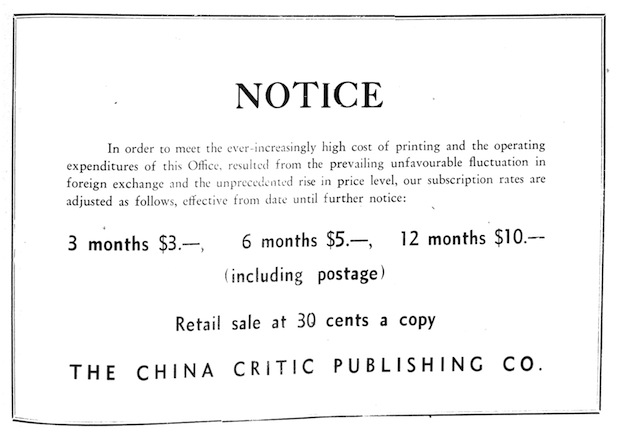

Fig.3 The China Critic is forced to increase subscription rates, 16 November

�

14 December

In 'The Jewish "Arbitration Court" in Shanghai', Joffre Y. Lu 盧峻 reports on the establishment of a court to settle disputes among the eighteen thousand Jewish refugees that have recently arrived in the city. Operating under the auspices of a benevolent society, the 'Committee for the Assistance of European Jewish Refugees in Shanghai', this court has handled over than 140 cases in the two months since it began. Detailing discrepancies between the operations of this new court and existing arbitration practices in Chinese law, Lu argues that the existence of the court constitutes the latest affront to Chinese territorial integrity:

Judging from the above facts no one will possibly deny that it is, in nature, a permanent judicial tribunal—an institution of public character. Its mere existence constitutes and encroachment on the integrity of the Chinese judicial system: its functioning amounts to the exercise of non-existent extra-territorial rights.

21 December

The Editorial 'Character Building' reports on the establishment of a National Cultural College in the wartime capital Chongqing, 'an outgrowth of the cultural reconstruction movement, which is being promoted by General Chiang Kai-shek to encourage the development of spiritual qualities among the people', with an emphasis on 'character building rather than mere book knowledge.' While the campus is still under construction, the writer discusses the likely content and emphasis of the school curriculum, particularly in relation toMr. Chang Chuan-li, the proposed president of the College who'is understood to have national socialist leanings':

The Chinese character differs far from the German-Japanese type, which easily submits to such regimentation. The Chinese are first and foremost individualists—too much so, at times, for the good of the nation. Training in co-operation and discipline will be all to the good. The Nazi emphasis on physical fitness could be well copied with advantage. There is very little danger of German National Socialism ever taking root in China, just as Russian Communism is an impossibility here.

In this same issue Lincoln J.C. Cheng 陳鎮球 contributes 'Time For the United States to Act', a discussion of American foreign policy since the 'Open Door' policy of 1899, and recent pressures within the US administration to become more decisively involved in the war.

1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | 1936 | 1937 | 1938 | 1939 | 1940 | 1945

|