|

|||||||||

|

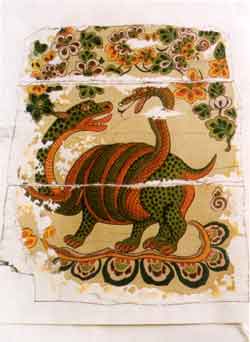

ARTICLESNEW DISCOVERIES IN QINGHAI Fig. 1 Tang dynasty painting on Red Bird on coffin panel unearthed from Dulan, Qinghai province The Yellow River rises in Qinghai, yet the cultural stamp of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau rests firmly on the history of Amdo, as Qinghai is known in Tibetan. Qinghai is not only home to unique northern neolithic cultures characterised by painted pottery that features inventive designs, but possibly to some of the earliest areas in which copper was worked. This area is sometimes described as having a distinctive Qiang (some say proto-Tibetan) ethnic underlay, and it has figured as a long-standing area of ethnic interchange and conflict down to modern times. Today Qinghai has sizeable Han, Tibetan, Mongol, Hui and Salar populations, to name only the largest ethnic groups, and many of Qinghai's toponyms, e.g., Minhe (lit., "ethnic harmony"), Xunhua (lit., "pacification and acculturation") and Gonghe (lit., "common accord"), record historical compacts, treaties and accords aimed at resolving conflict. This ongoing history of ethnic conflict is highlighted vividly in an article in the 26 March 2004 issue of China Cultural Relics News by veteran archaeologist Zhao Xin, who, recalling his visit in 1958 to Qinghai to examine the mummy of a Mongol warrior who died on the battlefield during the Yuan dynasty, noted that ethnic tensions were running high during his trip because of an ongoing Tibetan uprising in Xining, one of the repercussions of events in Lhasa that climaxed in the flight of the Dalai Lama to India.  Fig. 2 Tang dynasty painting of Xuanwu guardian beast on coffin panel unearthed from Dulan, Qinghai province Ethnic conflict and blending have long characterised Qinghai's history. By the 1990s it was abundantly clear to Xu Xinguo, head of the Qinghai Provincial Cultural Relics and Archaeology Institute, that the fabulous silk textiles (see Fig. 3), some of them 1,500 years old, which he was discovering in tombs in Qinghai's Dulan county were evidence of far-flung and diverse ethnic resonances. The presence of distinctive Central Asian, Persian and Chinese silks dating from a time contemporary with the Tang dynasty when the Dulan area was the centre of a mixed Tubo (Tibetan) and Tuyuhun (Murong Xianbei) polity began to attract international attention, and it became clear to scholars that his discoveries called for rewriting chapters in the history of Sino-Western trade and interaction. To date, 350 examples of silk fabrics have been unearthed in Qinghai and these have been identified by Xu Xinguo and Zhao Feng of the Hangzhou China Silk Museum as belonging to 130 categories - 112 types produced in "China" and 18 from Central and Western Asia, although this classification is complicated by our lack of knowledge today of the location of silk workshops of the time and the ethnicity of the artisans working at those workshops. Discoveries by Xu Xinguo over the past few years have revealed some of the most culturally complex finds to date, and these have made it abundantly clear that Xu Xinguo was correct and the Silk Road did indeed pass through Qinghai during the Tang period. Recent discoveries include unusual silver sculptural pieces,possibly of Sogdian provenance or inspiration, and of Byzantine coins. These underscore the point that significant trading routes ran through Qinghai, qualifying the corridor stretching from Xining to Golmud along the southern perimeters of both Kokonur (Qinghai Lake) and the Qaidam Basin as a Silk Road artery of significance. Dulan county was a hub of communications extending in different directions to Sichuan, Tibet and Central Asia, and along the Hexi Corridor to China in the Southern and Northern Dynasties and Sui-Tang period. In 2002 Xu Xinguo's discovery of painted coffin panels, the first known paintings of the Tubo-Tuyuhun period, during the excavation of two robbed tombs at Guolimu on the southern shore of Bayin Lake located 30 km east of Delingha city only serves to reinforce the picture of ethnic complexity that has emerged from Qinghai, making it clear that the Dulan area was a major centre during the pre-Tang and Tang periods. He outlined these most recent discoveries in the March 2004 issue of Cultural Relics World, arguing that these finds confirm his long-held belief that the Dulan area and its surrounds was the centre of a Tubo-Tuyuhun royal polity and that many of the graves discovered to date are those of the royal aristocracy that once dominated the area. In August 2002 the Qinghai Provincial Cultural Relics and Archaeology Institute and Haixi Prefectural Ethnology Museum jointly excavated the two tombs at Guolimu which are rectangular vertical pit graves with passageways leading to the tombs. One was a larger grave containing a wooden coffin enclosure or "outer coffin", called a guo in Chinese; the other was simply a pit sealed with a cypress board. The larger was a joint burial of a male and female couple, while the earth pit tomb held a single secondary burial. The secondary burial is distinctive because the scattered bones of the deceased were placed in a small coffin which was placed in turn inside a larger coffin. The discovery of a lacquer sword scabbard indicates that the tomb occupant had been a warrior. Both graves contain evidence of animal sacrifice. To either side of the buried couple, the complete skeletons of a horse and a camel were discovered. On the cypress board sealing the secondary burial were the scattered bones of a sheep. Animal sacrifice had a special significance in the Bön religion of the Tubo, still practised and indeed growing in Tibet, Qinghai and other parts of western China, because it was believed animals served as spiritual guides and companions of the deceased undertaking their ascent through the red mountains of the west to paradise. The joint burial also contained a large quantity of silks – brocades, gossamer silks, damasks, thin satin and silk gauze fabrics, as well as a wooden bowl, a bird carved from wood, and a wooden saddle; the secondary burial contained fragments of silk fabrics, a wooden bird, a wooden saddle and the lacquer scabbard.  Fig. 3 Tang dynasty fine silk (ling) with persimmon pattern against yellow ground unearthed in Dulan, Qinghai province The panels of the three coffins in the two tombs at Guolimu were painted with illustrations. The end panels of the coffins depicted images of the Four Divine Beasts (sishen). The four beasts - Blue Dragon, White Tiger, Red Bird (see Fig. 1) and Black Xuanwu (a composite creature comprising an intertwined snake and turtle, see Fig. 2) – were protective deities aligned to each of the four cardinal points, and used to decorate Chinese coffins and tombs from the Warring States period onwards. The side panels of the coffins feature paintings that draw on the array of significant scenes from the lives of the deceased that delineate social station and which provide a familiar repertoire of iconography in Chinese tombs. In these scenes of hunting, banquets, receptions, tributary missions and commercial activities graves centred around the yurt of the male and female occupants of one tomb, Xu Xinguo argues that the central figures are a tsan-pu (Tubo-Tibetan king) and tsan-meng (his queen consort). These topics and themes can also be found in some of the murals and carved stone illustrations that decorate Chinese tombs from the Han dynasty onwards. Clearly Chinese cultural notions of kingship and aristocratic social interaction were emulated far from the Central Plains region but the eclectic mode of burial adhered to at these two tombs indicates religious complexity. Throughout northern Chinese history an underlying cultural continuity and ethnic stability are often subjected to overlays of ethnically diverse mobile polities that legitimise their power through an iconography necessarily drawn from all strata, ethnic or otherwise, on which their power rests. The Four Divine Beasts were fashionable as tomb illustrations in the Tang dynasty. Although intended to quell malign influences emanating from the four cardinal directions to which they were aligned, the beasts on the Guolimu panels appear only on the panels at the head and foot of the coffins. The beasts are enclosed within floral borders, comprising honeysuckle, lotus blossom and vaporous cloud motifs, distinguishing them from other Tang dynasty representations of these tomb guardians. Xu Xinguo attributes this mode of framing the beasts to "influences from art further west", and the hunting scene that appears as a detail on one of the panels is also suggestive of Sasanian and Sogdian art, although the vegetation in that scene bears the hallmarks of a Central Plains style. However, the illustrations of these panels prepared by Xu Xinguo that appear in Cultural Relics World (two of which are reproduced here) convey none of the raw vibrancy and colour of the original works, slides of which he presented at a conference on Tibetan art and archaeology in late 2004 in Beijing. The Guolimu panels also include a fragment of the only known illustration of a Tubo commercial caravan. Located at the centre of the left coffin panel, the painting of a laden camel and merchants makes it clear that Dulan's Tubo-Tuyuhun polity relied on mercantile activity. The scale of these activities can perhaps be glimpsed in the historical record, and Xu Xinguo cites a reference in "Records of the Tuyuhun" in Official History of the Northern Zhou (Zhou shu) to a caravan comprising 600 camels and 240 Central Asian merchants that set out from Liangzhou, to the east of Dulan along the Hexi Corridor.  Fig. 4 Tang dynasty fine silk (ling) with floral pattern against purple ground unearthed in Dulan, Qinghai province A banqueting scene occupies the centre of another panel. The host and hostess are making a toast, and the wine in question Xu Xinguo posits to be the Tibetan single-fermentation wine with a low alcoholic content called stsang or rtsang (later known as chang), rather than the double-fermentation wine called arag (clearly of Turkic-Mongol origin or introduction) that appears only in Tibetan records of the 12th and 13th century. He further hypothesizes that this toast marks the conclusion of a treaty or accord. Xu Xinguo has been convinced for nearly two decades that several of the tombs found in the Dulan are royal tombs, both because of their dimensions (the tumulus covering tomb M1 in Reshui, Dulan is today 12m in height) and the discovery of an ancient Tibetan slip interpreted to include the word "king" at one of the tombs. He is also convinced that the actual tomb chamber lies under the tumulus and that the spectacular discoveries on the top of the tomb were only a shrine. Textual records also suggest that a major capital city of the Tubo-Tuyuhun state was located in the Dulan area, perhaps towards Qinghai Lake or on the edges of the Qaidam Depression, but there are several contending sites and no major excavation has been conducted. It is generally assumed by Chinese archaeologists that tomb murals and illustrations reflect accurately the daily lives of the tomb occupants. This literal reading of imagery may preclude the idealistic intention of the mortuary artists. Xu Xinguo identifies the tomb occupants – the central figures in the scenes on the Guolimu panels – as Tubo royalty. He bases his interpretation on an iconographic comparison with the cliff carving of an early Tubo period illustration of Princess Wencheng, Chinese consort of the Tibetan king Srongtsan Gampo, paying her respects to Sakyamuni Buddha. The carved image is found in Leba Gorge in Yushu (Tibetan: Üshug), Qinghai province. The gestures, arrangement of figures and mode of indicating respect parallel these elements in the Guolimu panel. The high conical hat worn by the tomb occupant in the toasting scene is similar to that worn by Srongtsan Gampo in the Leba gorge rock carving. Cattle were venerated by practitioners of the Bön religion, often loosely characterised as "shamanism". In Tubo stone carvings found in Qinghai, wild oxen, yaks and Chinese huangniu (lit., "yellow oxen") can be clearly discerned. Within Bön the white yak is identified with spirits of mountains and the earth, while the black and white yak, of the type being sacrificed to the side of the toasting scene in the Guolimu panel, signifies the interaction of the natural and human worlds. Large quantities of oxen were sacrificed to seal treaties concluded between Tang and Tubo rulers. The yak in the Guolimu panel is being killed by an archer firing an arrow directly into the jugular vein of the animal. The man wears a high conical hat, an elaborate cloak and lower over-garments, and knee-length black leather boots. According to the modern Tibetan scholar Gedun Chepal, the dress of the Tubo kings and their officials was adopted from Iran, and these paintings would confirm that hypothesis, according to Xu Xinguo. The latest archaeological finds indicate that the ancient Silk Road's Qinghai section may have been one of the busiest caravan routes used by merchants travelling between China and the Middle East. Xu Xinguo, head of the Qinghai Provincial Cultural Relics and Archaeology Institute, said that some 1,500 years ago, the Qinghai-section running west past the present-day Xining city and the Qaidam Basin to the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region may have been more prosperous than the well-known route through Xi'an and the Gansu corridor to Xinjiang. According to Xu, many priceless archaeological discoveries including two ancient Roman gold coins, scores of Sogdian silverware artefacts and more than 350 silk items falling into 130 categories have been unearthed from tombs along the Qinghai section (see Figs. 3 and 4). As the excavation sites outnumber those discovered along the Gansu Corridor section of the Silk Road and span a longer period of time, Xu maintains that the Qinghai section" was not just an auxiliary route, as most people had thought, taken by merchants only after the Gansu Corridor section was blocked by war. Lin Meicun, an archaeologist from Peking University, said that the latest discovery of a Byzantine gold coin in Dulan county provides more convincing evidence of past prosperity. After having inspected the cultural relics unearthed from the Tubo tombs in Dulan, Lin now believes that Qinghai began to prosper around the time of the Southern and Northern Dynasties (386-589) and entered its heyday in the Tang dynasty (618-907). Apart from the silk fabrics unearthed in Dulan, many lacquer, gold and silk wares of the Han dynasty (206 BCE -220 CE) as well as Persian silver coins have been excavated, indicating the then brisk trade contacts. The antiquity of the Silk Road, currently touted by some Chinese advocates as a nominee for listing as a UNESCO World Heritage site, was underscored by the discovery in mid-2004 of the skeletons of "three Europeans" dated to 1,900 years ago in Zhongchuan, a town in Qinghai's Minhe Hui-Tu Autonomous County. Wang Minghui, a palaeo-anthropologist from the Institute of Archaeology under CASS made the identification. The skeletons were found in two of nine tombs of the Han dynasty being excavated in Zhongchuan. Ren Xiaoyan, deputy-director of the provincial archaeological institute, makes it clear that the burial style shows that the "three Europeans" of indeterminate provenance were assimilated to a Han lifestyle, and the tombs contain no evidence of more precise origins. Xu Xinguo has long worked for the protection of the Dulan site. In January 2005 the construction of the Dulan Tubo-Tuyuhun Cultural Conservation Centre (Dulan Tubo Tuyuhun Wenhua Baohu Zhongxin) was completed. With a floor space of 10,000 sq m, the ersatz Tibetan-style building will function as a site museum under the auspices of the Qinghai Provincial Cultural Relics and Archaeology Institute. |