|

ARTICLES

The Intelligence, Blood and Sweat of the Labouring Masses | China Heritage Quarterly

The Intelligence, Blood and Sweat of the Labouring Masses:

The Palace Museum in the Cultural Revolution

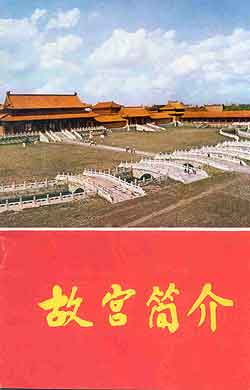

Fig. 1 Cover of pamphlet prepared as a 'handbook' of the Palace Museum on the occasion of its reopening after the Cultural Revolution. The Calligraphy is by Guo Moruo.

Although Zhou Enlai announced the formal beginning of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution on 1 May 1966 at a massive rally to celebrate International Workers Day in Tian'anmen, it was not until 16 May that the Politburo established the Cultural Revolution Group, comprising Jiang Qing and other radicals. Although there is a general belief that the Palace Museum (Fig. 1) escaped the depredations of the Cultural Revolution, thanks to protection extended by Premier Zhou Enlai, this is not entirely true.

In June 1966, a group of radical youth wrote slogans calling for the overthrow of the Forbidden City on its walls, and in late June, the Central Cultural Revolution Group, headed by Jiang Qing, sent a work team into the Palace Museum to assess the 'revolutionary consciousness' of the museum's staff. With the spark of the Cultural Revolution brought within the museum's walls, the southern 'Outer Court' was subject to contrived and controlled damage, as well as the staging of dramatic and intimidating enactments and tableaux. In addition, 'a rectification of names' was carried out, with plaques removed from many of the main palace buildings by museum workers filled with revolutionary zeal.

The Outer Court was the ceremonial quarter of the imperial palace containing the 'Three Front Halls'—Taihe Dian, Zhonghe Dian, and, Baohe Dian. Taihe Dian was the imperial 'coronation hall', as well as the setting for imperial celebrations of the New Year, royal birthdays and 'state receptions.' When emperors made their passage to Taihe Dian to oversee state ceremonies, they would rest in Zhonghe Dian. As a consequence, Zhonghe Dian was renamed by Cultural Revolution zealots the 'People's Restroom' (Renmin Xiuxishi), its throne was torn out and at the centre of the room ten chairs were placed around a long table on which several newspapers were placed. In this institutional reading room, 'revolutionary' museum workers could now attempt to fathom the latest directives emanating from across the walls to the west in Zhongnan Hai.

On 18 August 1966, during what is known as 'Red August' (hong bayue), Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, Lin Biao and other leaders presided over an enormous demonstration of support for the Cultural Revolution in Tian'anmen Square. The event had been orchestrated by Jiang Qing and the Cultural Revolution Group. On this day, the 'Red Guards' first made their appearance, and they pledged to pillage ancient monuments and cultural relics in Beijing as part of the movement to destroy the 'Four Olds', defined as 'old ideology, old thought, old habits and old customs.' Although sources disagree on the dates and details, it would seem that, on that same day, Zhou Enlai learned that some Red Guards were preparing to enter the Forbidden City to destroy the 'Four Olds', so he called an urgent meeting that night and issued a directive through the Ministry of Culture immediately closing the Palace Museum. The Beijing Garrison Command was also ordered to send troops to take up defensive positions around the perimeter of the Forbidden City. When the Red Guards returned on the following day they found the palace gates firmly closed by museum staff, so they erected a plaque on the outside of Shenwu Gate that read 'Xuelei Gong' (Palace of Blood and Tears). To the gate's outer walls they affixed the slogans 'Huoshao Zijincheng' (Burn the Forbidden City to the ground) and 'Zalan Gugong' (Trample the Gugong), evoking the language used in Chinese writings to describe the razing of the Yuanming Yuan by the Anglo-French Expeditionary Force a century earlier.

Fig. 2 Seated landlord from the sculptural series Shouzu yuan (Rent collection courtyard)

In April 1967, a group of the Rebel Faction (Zaofanpai) of Red Guards from Tianjin planned to drive a truck through the gates of the Forbidden City, but they were thwarted by garrison troops, according to one report, which may explain why, in May 1967, an entire battalion from the Beijing Garrison Command took up residence in the Forbidden City. In 1968, some People's Liberation Army (PLA) forces and the Mao Zedong Workers' Propaganda Team entered the museum and set about establishing a revolutionary committee to form the new management of the museum. In August 1969, many museum staffers were sent to the Ministry of Culture's May 7th Cadre School in Hebei province, leaving only 200 workers resident in the museum.

The ascendancy of the PLA and the Cultural Revolution Group throughout the Cultural Revolution has led to constant charges in later years that leaders from these groups took items from the Palace Museum. Mentioned frequently in reminiscences, the reliability of which cannot be checked readily, are the PLA leaders Li Zuopeng, Wu Faxian and Qiu Huizuo (although Lin Biao and his next of kin are not named), as well as all 'Gang of Four' members, with the exception of Jiang Qing. Li Zuopeng, political commissar of the PLA's navy, figures prominently in oral histories and he is said to have removed truckloads of precious artefacts, including the Song dynasty masterpiece Qingming shanghe tu. These unofficial reports state that although Zhang Chunqiao and Kang Sheng returned the cultural relics they 'borrowed', Qingming shanghe tu and the other treasures purloined by Li Zuopeng were only recovered from his home after his arrest in 1976.

Fig. 3 Detail of figures from Shouzu yuan (Rent collection courtyard)

For the workers in the Palace Museum the Cultural Revolution came to an end in September 1970, when Zhou Enlai visited the museum late one night and told the assembled staff that the museum had to be prepared for re-opening within a year. This order was issued in anticipation of a possible visit to China by President Richard Nixon, although no-one working in the museum was told this. The Palace Museum formally reopened on 5 July 1971, but it continued to be run by the revolutionary committee until January 1973 and it was not until 1979 that its scholarly journal resumed publication.

Fig. 4 Detail of figure from Shouzu yuan (Rent collection courtyard)

Only once between18 August 1966 and 5 July 1971 was any part of the Palace Museum opened to the public. On 2 December 1966, Fengxian Hall, which now houses the museum's clock collection, staged an exhibition of reproductions of the clay sculptural series Shouzu yuan (Rent collection courtyard) (Figs. 2, 3 and 4).

The original work, then said to have been produced by an anonymous group of 'proletarian' sculptors from the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts, comprised 114 figures. It graphically depicted the exploitation of rural serfs compelled to deliver grain and rent to an exacting and cruel landlord, Liu Wencai, through a sequence of tableaux culminating in a scene of peasant defiance. On completion, the clay sculptures were displayed on 1 October 1965, as an exemplary model for 'class education' in a rural courtyard in Dayi county, Sichuan. The sculptures were described variously in the media as 'a revolution in the history of sculpture,' 'an atom bomb' and 'a new beginning in the history of art.'

In March 1966, before the outbreak of the Cultural Revolution, the originals were brought to Beijing for display in the China Museum of Fine Arts. The exhibition proved so popular over its first few months that it was decided that the pieces be copied and displayed in the Palace Museum's more spacious Fengxian Hall. The copies were produced by teachers and students from the Central Academy of Fine Arts and the Central Academy of Arts and Crafts, working under the supervision of the original designers from Sichuan. From September 1966 onwards, the team worked to complete the project in Fengxian Hall itself. On 2 December 1966, the completed work, with five extra figures, was exhibited in Cultural Revolution Beijing, but only for a single day. [BGD]

References:

www.morningsun.org/stages/rent_courtyard_intro.html

Rent Collection Courtyard: Sculptures of Oppression and Revolt, Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1968.

|