|

|||||||||

|

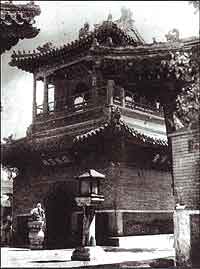

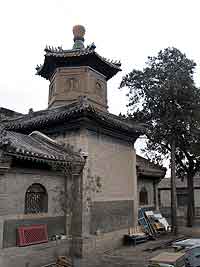

ARTICLESRestorations: Olympic Torch Or Rural Touch? Fig. 1 Niujie Mosque, entrance to the main prayer hall. The roof of the hall was built in three different periods. This, the outermost roof, is the latest addition, built in the Kangxi reign (late-seventeenth century) in imitation of the largest section of roof built in the Ming dynasty. As Beijing prepares to host the 2008 Olympic Games, it seems as though virtually every heritage building in the city is under scaffolding. The mania for renovation has also extended to the two mosques in the Beijing metropolitan area that survived the first three decades of Maoist urban development with their main prayer halls intact. These are the mosques at Niujie and Dongsi, which have together received the lion's share of municipal funds earmarked for the renovation of Islamic buildings. (Figs 1 & 2) The prayer halls of both mosques display what is typical of mid-Qing imperial architecture; this "classic" look has been enhanced in recent years by a series of restorations culminating in the recent pre-Olympics refurbishment. ![Fig. 2 Dongsi Mosque, entrance to the main prayer hall. [AHG]](005/_pix/chn5refurbDongsiDian.jpg) Fig. 2 Dongsi Mosque, entrance to the main prayer hall. [AHG] One has to travel outside the metropolitan area of Beijing municipality to find well-preserved examples of Chinese mosques in architectural styles other than that of the mid-Qing period. This is partly because Maoist era iconoclasm was less uniform in rural areas, but also because the post-Maoist effort to "restore" the old has had less predictable effects on buildings in the outlying areas of Beijing than it has had on those in the old city district that come under the heritage management of the Beijing Cultural Relics Bureau. ![Fig. 3 Xiguanshi Mosque, wooden window screen with carved swastika design. [AHG]](005/_pix/chn5mosquexishi21.jpg) Fig. 3 Xiguanshi Mosque, wooden window screen with carved swastika design. [AHG] The Niujie and Dongsi mosques are both listed as key heritage sites, and the imams at those mosques received their education at the main Islamic school run by the central government. When renovating any old building, decisions are made as to which authentic aspects of the building are to be restored, and which of the later additions are to be removed. As a result of the close relationship between the Niujie and Dongsi mosques and the central government, those features that have been deemed to be authentic reflect the central tradition of Beijing's architectural heritage, as defined by Qing-era dynastic imperial palaces and temples. By contrast, aspects of the mosque that reflect architectural fashions of the Republican period, for example, are removed. This article reviews the recent renovation work at the Niujie and Dongsi mosques and takes a brief tour through the mosque in Xiguanshi village, an example of a well-preserved heritage building in Beijing municipality outside the old imperial centre. (Fig. 3) NIUJIE MOSQUE Fig. 4 Niujie Mosque, interior of the main prayer hall. The latest renovation has attempted to restore the Kangxi layer of the mosque's architectural history, evident here in the decorative patterns used on the pillars and beams of the building. [AHG] Niujie Mosque, listed as a key national-level heritage site, reopened in October 2005 for the Eid festival, which celebrates the end of the fasting month of Ramadan. A renovation program that has been carried out in stages over several years is now nearing completion. This program has attempted to restore the buildings around the main courtyard to the state they were in following the last full-scale restoration in 1696, and has also involved the reconstruction of buildings in and around the back courtyard that were built in 1902. When completed, the program will have cost an estimated RMB28 million.  Fig. 5 Niujie Mosque, section of ceiling panels at the front of the prayer hall. A similar pattern is found on the ceilings of many imperial buildings in Beijing. [AHG]  Fig. 6 Niujie Mosque, southern flank of the main prayer hall. This mosque has been renovated and rebuilt on a regular basis over the last millennium, and displays architectural styles of many different periods. This sequence of archways was built in 1496 as part of the main renovation of the Ming dynasty. The low ceiling over a large floor area is the result of the roof being formed from separate pitched sections built at different periods of time. Large mosques in north China tend to have been built in stages, starting with a small hall and western-facing prayer niche, which is then expanded by attaching new, successive roof sections to the back wall of the established prayer hall. [AHG] Thanks to the existence of a brief gazetteer related to the mosque written in the Kangxi reign of the Qing dynasty (late-17th century), the architectural history of Niujie Mosque is better documented than that of any other mosque in the country. This gazetteer reveals that the mosque was built, renovated, extended or rebuilt by every political regime that has ruled Beijing since the Liao dynasty (907-1125). This tradition was subsequently observed by both the pre-Nationalist Republicans and the Japanese. The decision to restore the mosque based on its appearance during the Kangxi period is understandable, as this is the period when the decorative style of Beijing's major imperial buildings came to be defined. The Kangxi style, or perhaps the Kang-Yong-Qian style, of the high Qing is most obvious in the interior of the main prayer hall. (Fig. 4) The ceiling at the front of the hall is decorated with square panels, on each of which is painted a circular design in red, yellow, turquoise and blue around one of the Names of God, written in Arabic script. (Figs 5 & 6) The same pattern decorates the ceilings in the main halls of the Forbidden City, where imperial dragons, rather than the Names of God, feature in the centre of each panel. A comparison of photographs of the Niujie panels taken in the 1990s and in 2006 shows that they have been carefully touched up, although the latest paint job only restores the Arabic calligraphy to the compromised condition of an earlier, less delicate renovation. The mosque does, however, contain architectural features that are not purely Sinitic. The low-hung ceiling over a vast floor space, divided by rows of pillars, is found in a number of mosques in northern China that have been steadily expanded over the centuries by the modular addition of new sections of roof. (Fig. 6) The roof of Niujie Mosque is made up of four self-supporting roof structures adjoined at the sides, rather than one soaring, beamed canopy, of the sort found in the main halls of the Forbidden City. The three different sections of the roof, originally built in the Liao, Ming and Qing periods can be clearly distinguished from the vantage point of the small but charming pathways to the front of the prayer hall. (Figs 7 & 8) Built into the front wall of the hall, looking onto the centre of the courtyard is a small, six-sided pavilion whose three outer sides have window openings covered by carved calligraphic screens. (Fig. 9) From the inside of the prayer hall, this pavilion serves as the niche indicating the direction of prayer. The inside of the pavilion's roof is decorated with an arabesque and six circular calligraphic motives that somehow escaped being re-touched in the 1980s. (Figs 10 & 11) ![Fig. 8 Northern side of the front courtyard. [AHG]](005/_pix/Niujie9.jpg) Fig. 8 Northern side of the front courtyard. [AHG] ![Fig. 7 Niujie Mosque, southern side of the front courtyard. [AHG]](005/_pix/Niujie11.jpg) Fig. 7 Niujie Mosque, southern side of the front courtyard. [AHG]  Fig. 9 The oldest section of the Niujie Mosque, a six-sided pavilion at the front of the main prayer hall first built in the Liao dynasty. The inside of this pavilion serves as the niche indicating the direction of prayer (mihrab). [AHG] ![Fig. 10 Inside roof of the pavilion. [AHG]](005/_pix/Niujie5.jpg) Fig. 10 Inside roof of the pavilion. [AHG] ![Fig. 11 Close-up of circular pattern from the inside roof of the pavilion. [AHG]](005/_pix/Niujie4.jpg) Fig. 11 Close-up of circular pattern from the inside roof of the pavilion. [AHG] DONGSI MOSQUEWork has now finished on a RMB13 million renovation of the Dongsi Mosque, listed as a municipal-level key heritage site. (Fig. 12) This money has been spent on re-painting, on a double-storey dormitory building that replaces the mosque school that once stood to the south of the current site, and on a new muezzin's tower. The dormitory building will prove useful if the museum and library it is intended to house proceed as promised. (Fig. 13) The story of the new muezzin's tower, on the other hand, takes some explaining. A brass, knob-shaped relic, 80cm high and weighing over fifty kilograms, has been stored at the Dongsi Mosque for over a century. (Fig. 14) No one seems to know where it came from before that, although cast on the knob is the date of its production: the 22nd year of the Chenghua reign of the Ming dynasty (1486). With the help of specialists from the Research Centre for Traditional Architecture of the Beijing City Cultural Relics Office, the knob was identified as the crown of a Ming dynasty muezzin's tower. The reconstruction of such a tower was added to the Olympics renovation brief for the Dongsi Mosque, and a design was drawn up, largely based on the knob-less muezzin's tower at Niujie Mosque. The original version of the Niujie tower was built in the Ming dynasty, however it was subject to major renovations in recent decades, and it is difficult to say what exactly remains of the original tower.  Fig. 13 A new building at Dongsi Mosque to be used as a museum and library of Islamic texts, and as a dormitory for resident students. The Dongsi Mosque houses the largest collection of Arabic and Persian manuscripts and old printed Islamic texts in Beijing. [AHG] ![Fig. 12 Dongsi Mosque, interior of main prayer hall. [AHG]](005/_pix/DongsiIMG_2094.jpg) Fig. 12 Dongsi Mosque, interior of main prayer hall. [AHG] The Ming-dynasty muezzin's tower has now been completed, although the muezzin has continued to give the call to prayer from the courtyard in front of the prayer hall rather than mount the new structure. (Fig. 15) As one would expect, the Dongsi tower looks much like the Niujie tower, but with an additional knob placed on top. From an aesthetic point of view, the money was not well spent: both this tower and the Niujie tower on which it was based are no more than reduced versions of the muezzin's tower that existed at Niujie during the Republican period. The current tower at Niujie does not have the same proportions as it did in the Republican period, let alone the Ming dynasty. (Figs 16, 17 & 18) Mosques in China rebuilt since the Cultural Revolution tend to be reduced interpretations of their originals, as is evident from a study of Republican-era photographs. In particular, their roofs have lost the magnanimous sweep typical of mid-Qing imperial buildings. This puzzling tower-building project at Dongsi Mosque is a reflection of the top-down, modular approach of the mosque management committees that are most closely tied to the Beijing government. ![Fig. 14 The brass knob that inspired the Mosque's management committee to commission the building of a new Ming-style muezzin's tower. [AHG]](005/_pix/chn5mosqueDongsiKnob.jpg) Fig. 14 The brass knob that inspired the Mosque's management committee to commission the building of a new Ming-style muezzin's tower. [AHG] ![Fig. 15 Outer courtyard of the Dongsi Mosque, with a view of the newly-installed knob atop the muezzin's tower. [AHG]](005/_pix/DongsiFrontCourtyard.jpg) Fig. 15 Outer courtyard of the Dongsi Mosque, with a view of the newly-installed knob atop the muezzin's tower. [AHG]  Fig. 16 The new muezzin's tower, Dongsi Mosque. [AHG]  Fig. 17 The muezzin's tower of Niujie Mosque, which was the main point of reference in designing the new Dongsi tower. The most obvious difference between this tower and the Dongsi tower is the presence of a stone chicken on the top of the roof, rather than a brass knob. [AHG] BEYOND THE OLD CITY WALLSThe diversity of architectural styles that existed amongst the mosques of Beijing prior to the Cultural Revolution has now disappeared. Much of that diversity was a product of the Republican period (1911-1949), when Muslims were relatively wealthy and many held prominent positions in Beijing society. Little effort has been made to restore this particular layer of the capital's cultural heritage, as can be seen in the "before" and "after" images of Andingmen Mosque, which is just north of the site of the old city wall. (Figs 19 & 20)  Fig. 18 The muezzin's tower at Niujie Mosque in the Republican period. The proportions of this building are more generous than the reconstructed muezzin's tower. It was the reconstructed tower that provided the blueprint for the new muezzin's tower at Dongsi Mosque.  Fig. 19 Andingmen Mosque, 1939.  Fig. 20 Andingmen Mosque, 1990. The best evidence of what mosques in the Beijing municipality looked like prior to the Cultural Revolution is found in some of the Muslim villages outside the metropolitan area. Here, there is less pressure to vacate land to make way for productive enterprises, and the closer involvement of the village community in managing the affairs of the mosque means that renovations occur more regularly and on a smaller scale. As an example, the mosque at Xueying Village, thirty kilometres to the south of Beijing, features century-old architrave paintings that are in excellent condition, rare examples of late-Qing paintings of Islamic iconographic objects. (Fig. 21) Another village with an impressive old mosque is Xiguanshi (West Market), near the western border of Beijing municipality with Hebei province. The front door and prayer hall of Xiguanshi Mosque survived the Cultural Revolution, (Figs 22 & 23) while other buildings owned by the mosque, such as the rows of sleeping quarters to the north and south of the main courtyard and a number of buildings to the east, were dismantled. The front section of the prayer hall and the muezzin's tower that rises directly above it are estimated to be five hundred years old. Their age is evident in the stone archways that surround the prayer niche, and in the multi-stage design of the roof. (Fig. 24) The survival of this prayer hall in such good condition may have had something to do with the remarkable brawn of the village's male residents, who all claim to have mastered at least one life-threatening kungfu move. This rich martial heritage is explained by the fact that Xiguanshi village was home to two of the eight biaoju of the Qing dynasty, which were imperially-commissioned companies of bodyguards employed to ensure the safe delivery of goods and money shipped throughout the Qing empire. A museum has been built in Xiguanshi to showcase the special history of the village. The exhibition reveals that Xiguanshi was the first overnight stopping-point of the imperial party that fled from Beijing to Xi'an (the so-called "Progress to the West" xi xun ) at the beginning of the twentieth century as the court escaped the Eight-Power Allied Forces during the Boxer Rebellion. Both the Empress Dowager Cixi and the Guangxu Emperor marked their visit by writing encomia for the village. Empty display cases for these and a list of other items of interest relating to the history of the mosque are a feature of the museum. The absent objects are believed to be in the safekeeping of the village party committee. [AHG]  Fig. 21 Architrave painting from the late-Qing dynasty, Xueying Mosque. [From Tong Tao, ed., Yisilanjiao yu Beijing] ReferencesHui Zongzheng, ed., Niujie qingzhensi, Beijing Niujie qingzhensi chuangjian yiqian nian jinian (Niujie Mosque: In commemoration of the thousand-year anniversary of Niujie Mosque, Beijing), Beijing: Jinri Zhongguo Chubanshe, 1996. Tong Tao, ed., Yisilanjiao yu Beijing qingzhensi wenhua (The Islamic religion and the mosque culture of Beijing), Beijing: Zhongyang Minzu Daxue Chubanshe, 2003. Zhao Shiying, Beijing Niujie zhishu, gang zhi (A gazetteer of Niujie, Beijing: a concise gazetteer), Beijing: Beijing Chubanshe, 1991 (compiled during the Kangxi reign, Qing dynasty).  Fig. 22 Front door into the courtyard of the Xiguanshi Mosque. [AHG]  Fig. 23 Xiguanshi Mosque, showing the oldest, western section of the building including the muezzin's tower. [AHG]  Fig. 24 Interior of Xiguanshi Mosque, showing the stone archways at the front of the prayer hall. [AHG] |