|

|||||||||

|

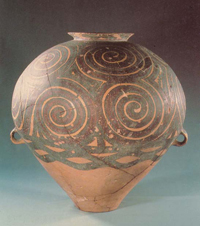

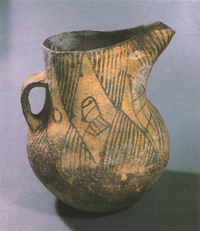

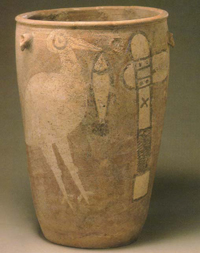

ARTICLESGenitalia, Totems and Painted Pottery: New Ceramic Discoveries in Gansu and Surrounding Areas Fig.1 Bottle of caitao ware with human-headed opening from collection of the Gansu Provincial Museum. From: Connoisseurs and Collectors (Shoucangjia), 2007:1, p.4, fig.4. While the north-west is seen today as an ethnic mix, it is also regarded by archaeologists as one of the homelands of Chinese neolithic culture. Both the Yellow and Yangtze rivers have their source in Qinghai. In the 1920s, the Swedish archaeologist Johan Gunar Andersson (1874-1960) documented some of the Chinese earliest neolithic culture sites there, after having unearthed the dominant Yangshao culture of the Central Plains region. Elements from Qinghai neolithic culture appear through the various genres of painted pottery (caitao) that have been found in eastern China. (Fig.2) The oldest Chinese worked copper was found to the west of Qinghai Lake and the Qin state, whose ruler unified China and declared himself Qin Shihuang in 221BCE, is believed to have been founded by proto-Tibetan Qiang peoples from Gansu.  Fig.2 Painted pottery bowl with 'human-faced fish' (renminyu) motif, Yangshao culture, unearthed in Banpo, Xi'an, Shaanxi Province, 1955. Height: 16.5 cm. Collection of the China National Museum.  Fig.3 Painted pottery weng pot with spiral pattern, Majiayao culture, unearthed in Yongdeng, Gansu province, 1974. Diameter at mouth: 19.7 cm. Collection of the Gansu Cultural Relics and Archaeology Institute.  Fig.4 Painted pottery connected jars Majiayao culture, unearthed in Minhe, Qinghai province, 1974. Height: 7.4 cm, Length: 25 cm Collection of the Qinghai Cultural Relics and Archaeology Institute. The most beautiful artefacts documenting the creativity of the neolithic inhabitants of China's north-west is provided by the painted pottery of the region. (Fig.3) Not only is the range of designs quite dazzling, but the wealth of shapes that were part of the (caitao) indicates a concern for functionality on the part of the early ceramicists who created these wares. (Fig.4) In Chinese archaeology the interpretation of ancient art motifs is particularly problematic. For archaeologists and art historians it is difficult enough to interpret art motifs on bronzes and in tomb paintings, but with prehistoric art the problems are greater as there is no ancient Chinese lexicon upon which they can draw. Recent discoveries of neolithic pottery in Gansu and adjacent areas have thrown a new light on an ongoing debate concerning the origins and significance of the designs that appear on Chinese neolithic painted pottery. These discoveries include: a 4,500 year old elephant-shaped pot found in Guanghe county, Gansu; a 4,000 year old pot with an illustration of an ostrich; a 3,500 year old pot said to be decorated with illustrations of male and female genitalia; and a 3,000 year old pot decorated with an image of grazing horses discovered in Minqin county. With the exception of the genitalia motifs they are all the first examples found to date of their type of decoration. These pottery finds were complemented by the discovery in Gansu of ceramic ballistas attesting to a hunting lifestyle. Novel animal motifsThe unearthing of the unique elephant-shaped pot was first reported in September 2004. It is significant because it shows that the bronze elephant-shaped zun vessels of the Shang and Western Zhou dynasties had ceramic forebears. The pot was found by farmers and is now stored in the Lanzhou Museum in Gansu. The red pottery pot, standing 9.5cm in height and measuring 8.5cm in diameter, has an elongated mouth and a proboscis like that of an elephant. There is no trunk. Wang Haidong, vice-chairman of the Gansu Provincial Painted Pottery Research Institute, said that previous archaeological discoveries have shown that patterns and shapes of pottery ware have much to do with the living environment of human beings, and so the discovery shows that elephants may have lived in Gansu area more than 4,000 years ago. Wang called the pot 'material evidence' not only for the study of ancient Chinese pottery culture, but also for the ancient ecological environment in the Gansu region. Apart from its unique elephant shape, the pot also has a wide, flat handle, surmounted by the image of a human face with clear-cut eyes, nose and mouth. In September 2004, Wang Haidong announced the discovery of the 3,000-year-old pot with a design showing a scene of horse-pasturing in Minqin county. The painted design shows a man herding eight horses. Some of the horses are bucking, some stand quietly; some have tails and some do not. All of the horses have large flanks, slender waists and thin legs. Surrounded by the eight horses, a broad-shouldered, slender-waisted man wears a long gown. The pot is 22cm high and 24cm in diameter. Its complex illustrations include alternating black and red broken lines. The most eye-catching of these pictures is the image of the man and the horses. According to Wang, this is the first example of ancient painted pottery depicting horse-pasturing discovered in China, providing clear confirmation that horses were domesticated in China as long as 3,000 years ago. Previously, only ancient painted pottery with images of donkeys, sheep, dogs and pigs had been found. The images of horses and the line-work of the painting are similar to those from the Tang dynasty (618-907). According to Wang, this indicates that the techniques for drawing horses used in the Tang could have been borrowed from ancient pottery painting. Even more remarkable was the early announcement by Wang in March 2004 that an ancient caitao pot with an ostrich design painted on the body, the first of its kind ever discovered in China, has been unearthed in Linyao city, Gansu. The pot stands 28cm in height and was discovered by local farmers. It has a pair of asymmetrical handles at the neck and the body, respectively. At the lower part of the pot are ten ostriches of different shapes and in various poses. Some are jumping and others are running. Some have two feet, while some have only one. Wang Haidong said this painted pottery piece dated back about 3,200 years and belongs to the Majiayao cultural type (c.3300 BCE-2050 BCE). Again, according to Wang, it is the first example of an ostrich design on a caitao vessel found in China and this suggests that 'it is possible that ostriches may have lived in the Gansu region about 3,000 years ago, providing an important clue for research on the ecological environment at that time'. Actually, it is more likely that this avian motif was introduced to China from Iran or Western Asia. Pottery East and West Fig.5 Painted pottery jug with spout, Hejing-Luntai system, unearthed in Luntai, Xinjiang. Height: 21.1 cm. Collection of the Xinjiang Cultural Relics and Archaeology Institute. Neolithic painted pottery (caitao) is associated with a number of archaeological cultures of China's north-west, specifically those distributed along the upper and central reaches of the Yellow River. However, types of painted pottery or pottery with painted decoration not technically classified as painted pottery have been discovered to the west in Xinjiang (Fig.5), south into Sichuan, as far north-west as Liaoning and among China's coastal archaeological cultures.  Fig.6 Painted pottery urn with images of stork, fish and stone axe, Yangshao culture, unearthed in Linru, Henan province, 1978. Collection of the Henan Museum. One of the earliest Chinese neolithic cultures to be identified and named archaeologically, Yangshao culture, is distinctive and readily recognisable because of its painted pottery that has become a signifier of the Chinese neolithic. (Fig.6) The culture takes its name from Yangshao village in Minchi county, Henan province, where the site was excavated and identified in 1921 by Johan Gunar Andersson. Later, in the northwest, Andersson found similar painted pottery. Today, Yangshao culture remains a distinctive archaeological culture, but the painted pottery found by Andersson in Henan is now classified as Miaodigou II culture ware. China's neolithic 'colour painted pottery' demonstrates remarkable design affinities with the pottery produced by neolithic cultures in such scattered locations as the Balkans and the Andes. Although for three decades following Andersson's discoveries most neolithic discoveries in northern China were classified as belonging to either the Yangshao or Longshan cultures, the picture today is extremely complex, with a plethora of cultures mirroring the dizzying number of identified neolithic sites. However, from the confusion of this classification, which often obscures more than it reveals, a number of major mid-late neolithic cultures of northern and central China associated with painted pottery have been identified. In the following highly simplified table, adapted from Simon Kwan's Chinese Neolithic Pottery, we can see that the main types are:

Fig.7 Painted pottery jar depicting relief carved female figure (detail), Machang culture, unearthed in Liuwan, Ledu, Qinghai Province. Height: 33.4 cm. Collection of the China National Museum The most common motif found on caitao wares is genitalia, with particular attention paid to the accurate depiction of female genitalia. (Fig.7) In March 2005, it was announced that a 4,500-year-old pot with patterns of genitalia was discovered in Lintao, Gansu province. Archaeologists identified it as belonging to the Banshan type of Majiayao culture and pointed out that this pot is the first Banshan type work to be found with patterns of both male and female genitalia. The discovery was described as being 'of great value for the study of fertility cults [shengzhiqi chongbai, literally 'genitalia worship'] in ancient China'. Neolithic sex is a topic much discussed over recent years, though often in a manner that is still stamped with the views of Lewis Henry Morgan and ideas contained in The Golden Bough. The identification of 'totems' is another obsession of Chinese prehistoric art historians.More interesting analytical work on primitive art in China focuses on the perception of patterns on painted pottery. With a nod towards reception theory and work on optical illusions and perception, scholars suggest that we should be looking at the non-painted shapes that appear in relief on painted pottery rather than concentrating solely on the painted motifs. The sequencing of motifs, rather than motifs taken in isolation, is also regarded by such scholars as being of greater significance. In other words, what is not depicted is of more importance than what is. (Figs 8 & 9)  Fig.8 Painted pottery jar with frog pattern from collection of the Gansu Provincial Museum. From: Connoisseurs and Collectors (Shoucangjia), 2007:1, p.9, fig.15. At the Second International Conference on Tibetan Archaeology and Arts (ICTAA II) held in Beijing in early September 2004, Wang Renxiang of the Institute of Archaeology of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences presented a new theory applying this view of painted pottery to prehistoric Tibetan pottery and its technique of reverse relief decoration. He used this theory to show the relationship between some types of pottery found in Tibet and their affinities with decorated pottery distributed over east and south-east Asia in the neolithic period.  Fig.9 Painted pottery bowl with spiral patterns from collection of the Gansu Provincial Museum. From: Connoisseurs and Collectors (Shoucangjia), 2007:1, p.6, fig.11. Returning to painted pottery, the new discoveries seem to indicate that even more interesting and exciting finds lie ahead. Perhaps Wang Donghai is correct, and the ostrich did once roam Gansu. In September 2004, Wang also announced the discovery of four ceramic balls, believed to be weapons of ancient hunters some 3,000 years ago, in Guanghe county. These weapons remind us of the bolos used for hunting rhea on the Argentinian pampas, and may after all lead us to discover that ostriches did in fact lead neolithic north-westerners on a chase. [BGD, © Bruce Gordon Doar] References:Kwan, Simon, B. Doar tr., Chinese Neolithic Pottery, Hong Kong: Muwen Tang Fine Arts Publication Ltd., 2005. Liu Bo, Qinghai caitao wenshi (Designs on painted pottery from Qinghai), Xining: Qinghai Renmin Chubanshe, 1989. Wang Guodong, 'Shilun Zhongguo shiqian caitaode qiyuan' (A discussion of the origins of prehistoric Chinese painted pottery), Kaogu yu Wenwu, 2005:2, pp.37-42. . |