|

||||||||||

|

ARTICLESA Bible for BeijingPierre Fuller

This essay originally appeared on 29 January 2009 in The China Beat. Pierre Fuller is a Doctoral Candidate in History at the University of California, Irvine. His dissertation concerns charity networks and local relief of the Great North China Famine of 1920-21. Our thanks to Jeffrey N. Wasserstrom for his recommending this article to us, and to both Pierre and Jeffrey for their kind permission to reproduce it here.—The Editor A few weeks ago my mother learned at her Greenwich, Connecticut, church that, beyond church grounds, Bibles cannot be purchased in the People's Republic. Her informant was a man from the Bible Society of Singapore who gave an evening talk on the state of Christianity in China at my parents' mainstream Protestant parish. My mother soon asked her son in Beijing, me, about this fact over the phone and I couldn't say either way: a Chinese-language Bible was not something I'd been actively looking for yet I could have sworn I'd spotted one in a shop a while back when living in China's Northwest. Then again, that was a long decade ago. I am clearly no expert on the subject. Then on a recent morning in a basement bookstore in the National Library in Beijing a volume with a black binding and gold lettering caught my eye. I pulled it off the shelf. In no shape to identify the Chinese word for 'Genesis' or for 'Psalms', I checked the volume's opening passage: 'Shen shuo: “Yao you guang”, jiu you le guang' 神说:要有光,就有了光 it read. God said: 'Let there be light', and there was light. I was holding a Bible. I took the book to the counter—its look was so plainly familiar it could have had the stamp of the Gideons on its cover—and without so much as a glance at my selection the cashier, while barking into a phone, rang it up. At fifty percent off, I thought, they're practically giving these away—and in the very belly of the National Library of the People's Republic of China, no less (a bookshop, it must be said, that was hardly as glamorous as its location might suggest, a labyrinthine afterthought with an uninspired selection). So much for my mother's stateside informant.

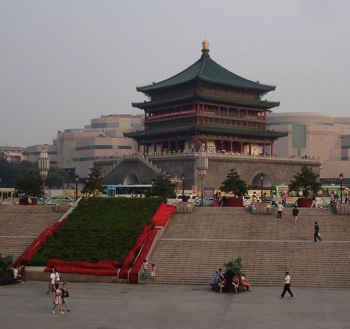

Returning to my research chores at the microfilm room upstairs I was reminded of a feature story I did for a Japanese daily a while back on the growing popularity of Christmas in China, specifically a very commercial version of it that I observed sprouting in 1990's Xi'an, the ancient capital. (One thing I was told by a church official then is that proselytizing in the PRC is legally limited to church grounds, but that hadn't stopped the draw of crowds at one downtown Xi'an church on Christmas Eve 1999 from requiring crowd control as bodies spilled out of the doors during the service. Mostly curious students, I was told.) Walking the city for material back then I came across a dramatic scene at a small church on the avenue running north from the city Bell Tower. A gaggle of old women were wailing at the steps of their church. At first I thought it might be a funeral; I quickly learned it was the funeral of the church building itself, a plastered structure suggesting 1980's construction. The building was condemned, the grounds beneath claimed for development, while the authorities promised to rebuild one for the parish in the outskirts of town. This meant a long commute to Sunday services and the women were adamantly opposed it. As for me, the foreigner with the notepad, I'd been sent by God himself, a teary-eyed woman announced, to let this be known to the world. The crowd around agreed. Overwhelmed, I escaped before any miracles could be expected of me. A year later an underground film project brought me to rural Liaoning Province in the Northeast where we were invited to informally film an animated Christian service at a towering village church, its choir decked in white and red vestments as they sang before a congregation of several hundred. I recall our hosts sporting T-shirts emblazoned with 'Jesus Saves' in red characters all that afternoon as they cooked us produce pulled, no doubt, from the neighboring fields. I couldn't have imagined a more idyllic atmosphere. But more significant was what occurred several days later in downtown Shenyang when the temptation to interview a ninety-year-old man occupying his daily sidewalk perch at our apartment building's side gate was too hard to resist. Naturally, our crew of three, Sony VX-1000 and boom mic in hand, attracted a crowd—and, soon enough, police, who escorted us back to our apartment to figure out what these foreigners (and one Chinese) were up to. We'd just been in the surrounding countryside filming quaint rural scenes but also the homes of residents, some very poor. That meant there were videotapes all over the house. But the authorities didn't even ask about that possibility. Some six hours at the precinct followed, many cigarettes passed around. The end decision was that we were to return with the offending tape (yes, we were allowed to take it home with us) the following business day. We did so, and sitting in a room with a plainclothes officer we ran through the content on a TV: the church service wasn't deemed objectionable; the humble interior of a 'peasant' abode? That had to go. I could understand the logic. Why not broadcast a thriving congregation? But a reminder of the rural majority languishing in poverty? That's no good. So we erased it right then and there and returned to our stockpile of other footage, our equipment intact, our visas unchanged. I would've thought the fist would've come down harder on us. Had we received special treatment because we were foreigners? Doubtless. But then we'd also been picked up precisely because we were white guys attracting a crowd to the otherwise innocuous interview of an old pensioner. And confiscating the equipment of these touring amateurs would hardly have warranted a call to Human Rights Watch. Someone could've made a few thousand bucks off our camera, easy. (A good thing no one thought of it, it was borrowed equipment.) Looking back, the plight of that Xi'an parish deserved to be told, but I didn't have it in me to write it then. Today, it strikes me as a scene straight out of Michael Meyer's newly published Last Days of Old Beijing, a moving account of the tragic face-lift and social dislocation of China's capital. As in much of Meyer's Beijing, the destructive forces on that ill-fated Xi'an church were a combination of cancerous developers given carte blanche to ruin and raze along with a cruel system of little warning to those affected, and no appeals. That plaster house of God could have been a much-needed clinic or neighborhood senior social parlor before the profits, 'prestige' and conveniences of 'development' tore it down. But I was hard-pressed to see Christianity in the equation. As for my new Chinese Bible, it'd be a challenge for me to get through it, so maybe I'll pass it on to a curious friend. Which brings me back to the Bible Society and its talk-China tour: It's easy to get sloppy when you're preaching to the choir. But if tracking Bibles is your business, at least get the facts straight. |