|

||||||||||

|

ARTICLESDimensions of Fidelity in Translation with Special Reference to ChineseYuen Ren Chao 趙元任

|

| Original | СПУТНИК |

| Graphological Translation | CHYTHNK |

| Transliteration | SPUTNIK [4] |

Another example is in the name of the

honor society in oriental languages at the University of California.

Because Chinese and Japanese are the major languages of the Orient,

its name in Greek letters is 'Phi Theta,' that is, 中日. Trivial

as such examples are, graphological translation may be of increasing

importance in view of the possibility of graphical scanning in machine

translation and other mechanical treatment of written text.

Translation proper begins when we deal

with meaningful units from morphemes and words on. While everyone is

more or less aware of the multiplicity of meanings for the same word,

translators often forget that the levels of units between languages

need not always correspond. For example, while Western translators usually

render correctly each character in classical Chinese into one word or

one morpheme, as in yii wei

(以為) 'take (it) to be,' suoo

yii (所以) 'wherewith,' swei ran

(雖然) 'although (it is) so,' they often overtranslate when handling

modern Chinese, in which many compounds should be translated as single

words. Thus, the forms in the preceding examples would be yiiwei

'to think (mistakenly),' suooyii

'therefore,' sweiran 'although.' As to the multiplicity

of meanings for the same word, it is usually a safe guide, as I. A.

Richards has observed (in a conversation with the writer), to tell whether

the same word occurring in different places is to be translated into

the same word or different words by noting whether the meanings come

under the same numbered definition in a monolingual dictionary. For

instance, the word 'nice' under number one goes into German

fein, under number two into German hübsch;

or, again, the word 'state,' under number one is German Zustand,

under number two, Staat. This is of course not to imply that

one language is more ambiguous than the other, since it works both ways.

Thus, we have:

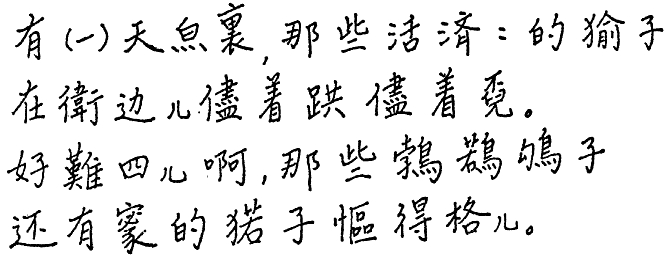

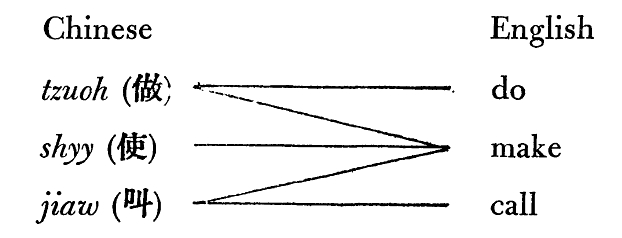

in which tzuoh

is ambiguously 'do' or 'make' and jiaw

is ambiguously 'make' or 'call,' while 'make' is ambiguously

tzuoh, shyy, or jiaw. Similarly, we have the following chain

ambiguities:

The most specific kind of context in

which a word or a sentence occurs is that of an actual instance of occurrence

in a situation. This constitutes what is in the terminology of communication

theory a token of the word or sentence as a type.

Thus, when Mencius interviewed King Huey of Liang and the king said:

'Soou 叟 (Sir) !'[5] the word soou

(which happened also to be a one-word sentence) was a token of the type

soou. Because philologists are chiefly concerned with the analysis

of actual texts in specific contexts, while linguists are primarily

interested in typical forms in general, I often characterize the difference

between the two disciplines by saying that philology is the study of

tokens and that linguistics is the study of types. Translation of a

historical text is then the translation of a token and should, after

adequate research in the context, yield a definitive translation of

the original. This is, however, only true in so far as the interpretation

of the original is concerned. Since the user of the translating language

and the hearer or reader may each vary as to his own background and

as to the circumstances of hearing or reading, there may still be the

necessity of differences in the translation even for the same specific

text. Hence the controversies over the old versus the new versions of

the Christian Bible, since to readers of the older generation the Authorized,

or Douay Rheims, version will have very definite associations and overtones

which they miss in the modern versions. On the other hand, the new generation

may possibly get better approximations to the effect of the original

from a modern version, so its defenders claim, than from an old version,

since it never grew up with it in the first place.

So much for the problems of size in

translation. Now, to examine more closely the various dimensions of

fidelity, one important dimension is that on the scale of semantic versus

functional fidelity. Is the translation to tell what the original means,

or is the translation to do what the original does in the given situation

of use? As an extreme case of purely functional translation, with zero

degree of semantic fidelity, I shall cite the example of Dr. P. C. Chang's

interpreting of the lectures by the famous female impersonator Mei Lan-fang.

This was how it went at the beginning of one of Mei's lectures in 1930:

Mei: 'Sheaudih jehshie ryhtz cherng gehwey inchyn jauday, jensh gaanshieh de heen.' (小弟這些日子承各位殷勤招待, 真是感謝的很)

Chang: 'The fundamental principle of Chinese drama is simplicity itself. '

and so it went on for the rest of the

hour.

But as examples of translation in a

more serious sense, take the sentence: Ne

vous dérangez pas, je vous en pris ! A semantic translation of it into English might be 'Do not disturb yourself, I pray you!' while a functional translation might be simply 'Please don't bother!' The second translation is functional because that is what one would say in English under the same circumstances. But if we look closer at the constituents being translated in this and in fact any other material for translation, we shall find that the difference between the semantic and the functional is a matter of degree. To be sure, there would be no point in equating dérangez to 'derange' since that would be giving the etymological cognate and not translating. But a close semantic translation could be 'disturb yourself.' On the other hand, 'l request you' for je

vous en pris is closer semantically, while 'please' is functionally

what one would more likely say in cases where one would say je

vous en pris. But isn't the meaning of a word in a context or in

fact isn't the meaning of any linguistic form that which one would normally

say under those circumstances? If so, then the best semantic fit in

a translation will have to be also functionally the most suitable to

use. The idea of semantic translation, however, is not completely without

meaning—no pun intended. By semantic translation one usually refers

to the most commonly met with meaning of a word, and, other things being

equal, to the etymologically earlier meaning. This is again a matter

of degree, since all semantic meaning is in one sense functional.

Correlated highly, though not identical, with the semantic-functional dimension, is that of literal versus idiomatic translation. The term literal is a misnomer, since it would seem to mean transliteration. In actual usage, of course, a literal translation means a word-for-word or morpheme-for-morpheme translation. The sign Tsyy Luh Bu Tong (此路不通) says literally 'This road doesn't go through,' but the idiomatic equivalent is 'Not a Through Street' (or 'No Thoroughfare' in England). Jau Tie Jih Sy (招貼卽撕) says literally 'Signs Pasted (will be) Immediately Torn,' but is idiomatically equivalent to 'Post No Bills.' From another point of view a literal translation may also be regarded as a fine-grained translation, but not necessarily of high overall fidelity if it is not idiomatic or functionally misleading. In this literal-idiomatic dimension there are also differences of degree on a sliding scale. Thus, between the French and the English forms of signs about smoking, there are the following possible steps to consider:

Prière de ne pas fumer Original 'Prayer of not a step to smoke' Literal translation 'Request of not smoking' Grammatical but not idiomatic 'No smoking, please' Idiomatically acceptable 'No smoking' The usual sign

There is one usage by which a literal

translation is applied to a smoother form than a word-for-word translation.

To quote again from Catford,[6] adding a comparison with Chinese, we

have:

English: It's raining cats and dogs Original French: II est pleuvant chats et chiens Word-for-word tr. II pleut des chats et des chiens. Literal tr. II pleut à verse. Free (idiom.) tr. Chinese: Ta sh shiahj mhau her gooumen. 他是下著貓和狗們. Shiahj mhau goou ne. 下著貓狗吶. (Yeu dah de jeanjyr sh) shiah mhau shiah goou Ie. (雨大的簡直是)下貓下狗了. Chingpern dah-yeu Ie. 傾盆大雨了.

Note that the French and the Chinese

happen to agree literally, too.

A word of warning should be said here

against the strong temptation to use an interesting literal translation

at the cost of fidelity in the other dimensions. If a translation is

both literal and idiomatic, well and good, as in the French and Chinese

above. Again, in: Ta bu hwai hao-yih

(他不懷好意) 'He doesn't harbor good intentions,' the equating of hwai

with 'harbor' is very apt. When 'The style is the man' is translated

as Wen ru chyi ren (文如其人), it is fairly close, though the Chinese

is in wenyan, while the English is neutral in that respect. When,

however, Shiawhuah! (笑話!) is equated to 'Ridiculous!' then

there are problems. For while the Chinese can be used either as non-polite

or as insulting language, the English can only be the latter if applied

to the person being spoken to. Even more subtle are the shades of differences

between donq₀syyle [7]

(凍死了) and 'frozen to death.' Most of the time, both are used either

in the literal sense or as a hyperbole and the Chinese form with or

without neutral tone can be used either way too. But depending upon

context, one may be idiomatic in one but not in the other language.

A very important dimension of fidelity

which translators often neglect is comparability in frequency of

occurrence, or the relative familiarity of the expressions in the

original and the translation. Too great a discrepancy in this respect

will affect fidelity, even though the translation is accurate in other

respects. As is well known in information theory, the less often a thing

is talked about, the more it means to talk about it. Sometimes the very

things one talks about may be a familiar thing in one culture and strange

and exotic in another. In such a case, if the thing is the main topic

of the discourse, it cannot be helped. An account of a game in the World

Series can very easily be translated into Japanese, but would make poor

reading in Chinese, in which terms about soccer are heard every day,

but not those of baseball. However, in cases where a familiar expression

is used casually as a figure of speech, then sometimes a translation

by a different figure of speech of the same import but with a comparable

degree of familiarity will result in a higher degree of overall fidelity

than an apparently faithful translation which is very unfamiliar. For

example, to speak of reaching the third base might be rendered, in Chinese,

as reaching the 'listening stage' in a game of mahjong, where the

apparently 'free' translation has greater fidelity, because it is

a better match in the frequency of occurrence. Technically, the third

base is in Chinese dihsan leei

(第三壘). But at the lecture on these problems of translation, at which

there were probably thirty or forty Chinese-speaking members of the

audience, I asked how many had heard the expression dihsan

leei and not one of them raised his hand. My daughter, Rulan Pian,

was in the audience, but did not raise her hand, because she had just

learned the term that same afternoon, as I had myself.

Before continuing with the consideration

of the other dimensions, let us consider for a moment one aspect of

the translation which has to do with the dimension of size, literalness,

and frequency, namely the phenomenon of calque,

or translation borrowing. In ordinary borrowing from one language to

another, a foreign word or expression is taken over and adapted to the

phonemes of the borrowing language, as for example, English menu

['meniu] or ['meiniu] from French menu

[məny], or English chopsuey from Cantonese dzaapsöy

(雜碎). In such cases, whether there is a change of meaning or not—and

usually there is—no translation is involved. In translation borrowing,

on the other hand, one translates the constituent parts of foreign words

and makes up new combinations, thus forming neologisms. For example,

the German noun for telephone

is Fernsprecher, tele- translated as fern-

and -phone freely translated as -sprecher.

On the other hand, in the verb telephonieren,

there is direct borrowing from the Greek (except for the addition of

the German verbal suffix). Another example is German Einfluss,

from Latin in + fluens.

Sometimes, especially in translation borrowings of phrases instead of

compound words, the borrowings may be so naturalized that most users

are hardly aware of their foreign origin. Examples are: 'That goes

without saying' < Ça va sans dire,

or the colloquial 'How goes it?' < Wie

geht's? 'Long time no see,' however, is not a translation borrowing,

since Hao jeou bu jiann Ie (好久不見了), if translation-borrowed, would

come out as 'Good long not met.'

Much more tricky are what I call skewed

translation borrowings. By a skewed translation borrowing I mean one

in which you translate a foreign word with meanings A, B,

C, D, etc. with a certain native word for meaning A

and then, instead of choosing other suitable words for the other meanings

B, C, D, etc., just go on using the same native word for

A mechanically whenever you see the foreign word. The result amounts

to an importation of foreign meanings which the native word never had

before. Present-day Chinese is full of such skewed translation borrowings,

such as:

Old meaning Added meaning weimiaw (微妙) 'delicate (of things)' 'delicate (of situations)' chyangdiaw (強調) 'stress (in pronunciations)' 'to emphasize' chingsuann (清算) 'liquidate (accounts)' 'liquidate (persons)' Iiisheangde (理想的) 'ideal (adj. of idea)' 'ideal (perfect)'

Such borrowings always take time before

they are quite naturalized and are mostly limited to journalistic language

or discourse in a journalistic style. Some of the new ones appearing

in headlines, especially in overseas Chinese newspapers, are hardly

intelligible without reading on in the text or retranslating them into

the source language. For example, one headline says that the crime rate

in San Francisco had a shihjiuhshinqde

(戲劇性的) decrease last month.[8] It made no sense to me until I realized

that shihjiuhshinqde did not mean 'theatrical,' but 'dramatic':

there was a dramatic decrease in crime rate. Another news item, about

a manifesto concerning the hydrogen bomb signed by Bertrand Russell,

Albert Einstein, and others, said in Chinese: 'Ever since the tests

at Bikini, lianghao de dangjyu (良好的當局)—excellent administrators—unanimously have pointed out the

danger that a war of hydrogen bombs can destroy the whole of mankind.'[9]

I had to read the column twice before I realized that what they called

lianghao de dangjyu was a skewed translation borrowing of 'good

authorities,' good authorities have pointed out etc. To be sure, this

sort of lazy man's translation is constantly being committed by students

in foreign language classrooms. But when a new meaning becomes established,

even though through foreign influence, it becomes part of the language—shall

I say lingo?—whether you like it or not. But I am sure that excellent

administrators for 'on good authority' is still unintelligible

at the present stage.

To continue with the consideration

of dimensions of fidelity, another dimension in which a translator may

fall into the trap of what may be called false fidelity is the presence

of obligatory categories in languages. A noun in English has

to be either singular or plural, a verb either present or past. A friend

in German has to be either male or female. A cousin in Chinese has to

be not only either male or female but also either on the father's side

or on the mother's side, either older or younger than oneself. What

a translator has to do is of course to omit the obligatory distinctions,

whether lexical or grammatical, if they are not obligatory in the translating

language and if they are not relevant in the context. For instance,

Chinese beau (表) is an adjective for relatives of different

surnames and mey (妹) is a female relative of the same generation

younger than oneself.[10] But if the obligatory distinctions do not

matter in a certain context, then the combination beaumey

can very well be undertranslated simply as 'cousin,' otherwise one

would have to say things like: 'Good morning, my femalecousin-on-mother's-or-

It is easy enough to take care of such

striking and obvious cases of obligatory categories, but it is the less

obvious cases that are more tricky and more easily mislead the translator.

Take the innocent-looking or sounding sentence: 'He put on his hat

and went on his way.' In nine cases out of ten, a French, a German,

or a Chinese student of English would translate it 'faithfully'

with the pronoun 'his' in both places, whereas if he were to start

composing the message in his own language, say in Chinese, he would

probably just say: Ta dayle mawtz

tzooule (他戴了帽子走了).[11]

Of course if overtranslation of obligatory

categories is written and gets read on a large scale, it can establish

a new usage, at first as a neologism, then as an accepted new style.

Thus, starting with an imperfect knowledge of the uses of tense in English,

a Chinese translator adds mechanically the suffix Ie

whenever he sees a verb in the past form, even though in his own talk

and writing he does not use the suffix Ie

in many instances of reference to the past. Again, he uses a preposition

bey (被) for 'by' whenever he sees a passive voice in the English

verb, unaware of the fact that Chinese verbs have no voice and the direction

of action of a verb works either way, depending upon context, and also

forgetting that the preposition bey

for passive action is used only before verbs with unfavorable meanings.

However, once this sort of translatese is written often enough, it gets

to be written in originals, even when no translation is involved. When

this happens, it constitutes what in linguistics is known as structural

borrowing, that is, instead of borrowing specific words or phrases discussed

above, one borrows functional ('empty') words or a whole type of

structure. So nowadays, one suffers not only scolding and beating but

also being praised or rewarded.

Besides the translation or omission

of obligatory categories, there is also the natural tendency, unless

one is on guard against it, to translate noun for noun, verb for verb,

or in the case of phrases, nominal for nominal expressions, verbal for

verbal expressions, etc. Other things being equal, this will of course

be a contributing factor toward fidelity. But since other things are

never equal, they must all be considered and given no more than proper

weight. For example, quelle merveille!

is a nominal expression, but to render it as 'what marvel!' would

be too strong, nor is it comparable in the dimension of frequency of

occurrence. Instead, 'how marvelous !' would have a higher degree

of overall fidelity, even though it is an adjectival and not a nominal

expression. Likewise, the adjectival phrase jen

taoyann (真討厭) is better translated by the nominal phrase 'what

a nuisance' than the adjectival phrase 'how annoying.' So is

jen haowal (很好玩ㄦ), an adjectival phrase, better translated by the

nominal phrase 'what fun,' whereas the corresponding adjectival

phrase 'how funny' would be entirely wrong. In Luen daw

nii le (輪到你了) 'It's your turn now,' luen

is a verb and 'turn' a noun. In Nah

sh shyunhwan de (那是循環的) 'It's a vicious circle,' shyunhwan

de is an adjective and 'circle' a noun, with 'vicious' understood

in the Chinese. A translator would be strongly tempted to translate

keeren (可人), which has a nominal root, as 'personable,' which,

however, is not as accurate as 'lovable,' with a verbal root.

Sometimes, especially in clichés and

proverbs, the most faithful translation will be of an entirely different

structure. In Woo terng (我疼), woo

is subject, but in 'It hurts' the 'me (understood)' is object.

Chii yeou tsyy lii (豈有此理) is a whole sentence in wenyan,

but used in speech as an adjective and should be translated as 'ridiculous.'

'I wish' followed by a contrary-to-fact clause could be equated

to Woo yuannyih…, as in Woo

yuannyih nii bye nemmyanql long

(我願意你別那麼樣ㄦ聾) 'I wish you were not quite so deaf,' but a closer translation

is ... (nah) dwo hao ([那]多好), preceded optionally by woo

yuannyih. Huu tour sher woei (虎頭蛇尾) lit. 'Tiger's head, snake's

tail' is a phrase of two nominal expressions; its equivalent 'anticlimax'

is one noun. Jiin-shanq tian hua

(錦上添花) and 'carrying coals to Newcastle' are fairly close in structure,

but its counterpart in Chinese sheue-lii

sonq tann (雪裏送炭), a verbal phrase, has its best equivalent in 'A

friend in need is a friend indeed,' which is a full sentence.

Sometimes, not only the form classes

do not need to correspond, but even radically different categories of

linguistic elements may turn out to be the best translational equivalent.

There is a very common grammatical form in Chinese consisting of a predicate,

which may be a verb or an adjective, followed by the verb 'to be'

sh(yh) (是), then followed by a repetition of the same predicate,

as in hao sh hao (好是好). One can analyze this as '(as for being)

good, (it) is good.' But this is really explaining the Chinese to

a student of the language and not actually translating it. How then

would you translate sentences of this type? Well, you translate this

Chinese formula of words into an intonation in English. The English

intonation which fits this Chinese formula best is what Harold E. Palmer

[12] calls 'the swan,' so-called because its time-pitch graph makes

a double turn like the neck of a swan. The plain statement Hao

means 'It's good': but in the form Hao

sh hao it means 'It's good ![]() (but).' It is of course also

possible to render this formula by such phrases as 'to be sure,'

or the more colloquial 'all right,' as in '(It's good) all right

(but).' It is of course also

possible to render this formula by such phrases as 'to be sure,'

or the more colloquial 'all right,' as in '(It's good) all right![]() ',' (with a low rising intonation), but the swan intonation

is about as faithful a translation of the Chinese formula as any translation

by the use of words. In extreme cases, language is even translated by

non-language, such as gesture, as mentioned above.

',' (with a low rising intonation), but the swan intonation

is about as faithful a translation of the Chinese formula as any translation

by the use of words. In extreme cases, language is even translated by

non-language, such as gesture, as mentioned above.

Similar to the problem of obligatory

categories, there is the problem of translating the endless varieties

in different cultures of the subcategories of things and qualities,

units of measure, money and coinage, names of colors, and the very names

of numbers themselves. English has no juotz

(桌子) 'table' – 'desk'; no shia

(蝦) 'shrimp' – 'prawn' – 'lobster'; no che

(車), since 'vehicle' would be out of style in most contexts;

no ta (他), though current Westernized writing differentiates

他: 她: 它; there is not even ren

(人), and 'man' often has to serve as 'woman.' When you call

a woman huay-ren (壞人) you can neither call her 'bad woman,'

nor 'bad man,' and 'bad person' would again be out of style,

and you may have to settle for 'bad girl.' There are four equally

common auxiliary verbs in Chinese: neng, keen,

keeyii, and huey (能, 肯, 可以, 會), with overlapping equivalences with

English 'can' and 'may,' with keen

equatable to the awkward and therefore less frequently used 'be willing

to.' There is only one word 'hot' for both tanq

(燙) for temperature and lah

(辣) for the taste. Among Chinese dialects, the sentence in Mandarin:

Jeh tang tay tyan, keesh bu gow shian

(這湯太甜, 可是不狗鮮) 'This soup is too sweet, but not tasty enough' would

be difficult to translate into Cantonese without some circumlocution,

as both tyan and shian

would be called dhim (甜) in Cantonese. In names of colors there

is no 'brown' in Chinese and there is no ching

(青) in English. Many languages have no word for a length comparable

to a yard, and the conception of teen-age would not be translatable

unless the language happens to have a common feature from thirteen to

nineteen. It is easy enough to translate such items, even with a high

degree of accuracy, if it is a matter of giving the mathematical, physical,

or economic equivalents. But since such expressions are often used for

other than their purely quantitative import, fidelity in the other dimensions

such as function, idiom, frequency, etc. will have greater weight. For

instance, for a language with no word for dozen, 'a couple of dozen'

will appear better as 'a couple of tens' than as 'about twenty-four.'

Incidentally, such linguistic and cultural differences sometimes even

affect wholly non-linguistic matters. Thus, it is not only often difficult

to translate 'quarter' into a language that has a dollar-like unit

but divides it into five twenty-cent pieces, but the existence of the

quarter (or 20-cent piece, as the case may be) actually affects the

prices of things that can be conveniently sold over the counter-and

in slot machines!—so that the dimension of frequency will be affected

in the translation of such items. Nobody would have said pas

un sou if there had not been such a coin as the sou.

Nobody would have said meiyeou

ig benqtz (蚌子) if there had not been such a coin as the square-holed

'cash.'

Style is another dimension in which

too much discrepancy will obviously affect the fidelity of translation.

One may jazz up serious literature into modern slang, but that would

be parody and not translation. Today's style in one language can of

course be best translated in today's style in another, especially if

the subject is one which is being talked about today. If it is a text

of a past age, the translation leads to problems. I have already mentioned

the problems involved in translating the Bible, and whole treatises

have been written about them. For example, that very readable book,

Trials of the Translator by Ronald Knox (New York, 1949), is mainly

concerned with such problems. As for the age of the languages involved,

there is no necessity, or even special virtue, in matching period with

period. Must one, for example, translate The Divine Comedy

in the language of The Canterbury

Tales? If such a translation already exists in its own right, well

and good, but there is no special virtue as to fidelity in matching

periods as such. Moreover, what if the text to be translated, say the

Chinese classics, was written long before the age of the translating

language, say before the formation of what might be called the English

language? The wise course in such a case, and this is the course that

has been commonly adopted by most translators of the older texts, is

to write in as timeless a style as possible. This practice, to be sure,

may involve a loss of color and life, but it will at least be free from

suggesting the wrong color. It is true that in the long run what seems

timeless to the translator of one age will eventually be dated and that

is why there had to be retranslations of important works, as people

have done with the Bible and as John Ciardi has been doing with his

'Englishment' of the Paradiso.[13] The important thing about

handling the older texts is that one should at least avoid the use of

local color and narrowly dated expressions. For nothing gets as easily

off color as that which is full of local color and nothing so quickly

out of date as that which is right up to date.

An extremely important but often neglected

dimension of fidelity is what might be called the sound effects of the

language. I refer to such elements as length, symmetry, and, in the

case of verse, meter, rhyme, and other prosodic elements. Now, since

the semantic range of words and the obligatory categories of two languages

never coincide, if all that is in the original has to be accounted for,

the translation will necessarily be longer; but in trying to include

everything and not to lose anything in the original, the translator

will unavoidably add extraneous elements because of overlapping categories

in the translating language. In practice, therefore, a translator will

have to make a compromise between the sins of omission and the sins

of commission and try to take into account all the dimensions of fidelity,

including that of aiming at comparability in length. Take the French

expression for talking nonsense et

patati et patata. If you translate it as 'gibberish,' it will

sound rather weakish; 'yak yak' is better, since it has a more similar

pattern, and 'yakety yakety' will be even closer to the sound effects

of the French et patati et patata.

Translating Woode shin putelputelde

tiaw (我的心撲忒ㄦ撲忒ㄦ的跳) as 'My heart palpitates' seems to give a pretty

close sound effect, but 'My heart goes thumpety thump' has the advantage

of comparability in length and style. To quote from John Ciardi: [14]

Every word has a certain muscularity.

That is to say, it involves certain speech muscles. Certainly any man

who is word-sensitive is likely to linger over the difference between

the long-drawn Italian carina

and the common, though imprecise, American usage 'cute' when applied

to an attractive child. The physical gestures the two words invite are

at least as different as the Italian child's goodbye wave ('Fa

ciao, carina') with the palm of the hand up, and the American

child's ('Wave bye-bye') with the back of the hand up.

Even street names have to be translated

with due regard to comparability in length. One writer, in making fun

of the street name 'Avenue of the Americas,' says: 'Yes, this

is the Street-of-the-Great-Leap Forward -of-our -glorious -People's

-Commune -System -over -the -Capitalist-Butchers-of-the-

In translating songs to be sung to

the same melody, the requirement of sound effects is of course even

more strict. Take, for example, the first two lines of Schubert's

Erlkönig:

| Wer | rei — | tet | so | spät | durch | Nacht | -und | -Wind? |

| 'Who | rides | +there | so | late | through | night | +so | +wild?' |

| -Es | -ist | +der | Va — | ter | mit | sei — | nem | Kind. |

| 'A | +lov — | ing | fa — | ther | with | his | +young | child.' |

Here the words marked + and - are those

which have been added or omitted, respectively, for reasons of rhyme

and rhythm. (Note also the bad stress pattern in 'his young.') The

preceding is still a fairly close translation. In the Haiden-Röslein,

however, the demands of rhyme and rhythm are so strong that there is

even no point in counting the pluses and minuses, as can be seen in

the opening lines:

| Sah | ein | Knab' | ein | Rös — | lein | steh'n, |

| 'Once | a | boy | a | wild — | rose | spied,' |

| Rös — | lein | auf | der | Hai — | den, | |

| 'In | the | hedge- | row | grow — | ing,' | |

| War | so | jung | und | mor — | gen | schön, |

| 'Fresh | in | all | her | youth — | ful | pride,' |

| Lief | er | schnell, | es | nah | zu | seh'n, |

| 'When | her | beau — | ties | he | de — | scried,' |

| Sah's | mit | vie — | len | Freu — | den. | |

| 'Joy | in | his | heart | was | glow — | ing.' [15] |

At the other extreme, as examples of

sacrifice of sound for the sense is the usual type of translation of

classical Chinese verse, such as that of the Book of Odes

by James Legge or T'ang poems by Arthur Waley, in which the number of

syllables is three or four times that of the original. While the message

and imagery is usually very well conveyed in such translations, they

give the feeling, to us who were raised in the concise and rhythmic

swing of the shorter lines, of big mouthfuls of dough, if indeed not

quite wey ru jyau lah (未如嚼蠟).

The more rhythmical is, however, not

necessarily the more concise. Take the no spitting notice on trains

of the Shanghai-Nanking Railway. The Chinese says:

Swei chuh tuu-tarn, 隨處吐痰 'Everywhere spit, Tzuey wei eh-shyi. 最為惡習 Most bad habit. Jih ree ren yann, 既惹人厭 It is loathsome Yow ay weysheng. 又礙衛生 And bad for health. Chejann yuehtair, 車站月台 Stations, platforms, You shiu chingjye. 尤須清潔 Must keep clean, neat. Taang yeou weiJann, 倘有違反 If you violate, Miann chyh moh guay. 面斥莫怪 We will rebuke.'

The translation above is more rhythmic

than literal. But the actual sign in English says in one sentence:

IN THE INTEREST OF CLEANLINESS AND PUBLIC HEALTH PASSENGERS ARE REQUESTED TO REFRAIN FROM SPITTING IN THE TRAINS OR WITHIN THE STATION'S PREMISES

To be sure, in the early days of that

railroad, which was run by foreigners, there were in the Chinese notice

overtones of the civilized management instructing those uncouth country

people how to behave, while the English version was in a language of

equals talking to equals. But the use of rhythmic forms in notices is

very common in Chinese in any case.

When, however, it is a matter of translation

between English and modern spoken Chinese, as I did for the Lewis Carroll

books, I did not have the handicap of having to work with such disparate

states of languages, and the rendering of sound effects was easier without

sacrificing as much fidelity in the other dimensions. In Through

the Looking-Glass [16] especially, I was able not only to

make point for point in the play on words but also keep practically

the same meter and rhyming patterns in all the verses. Take, for instance,

the first stanza in Jabberwocky:

'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe.

All mimsy were the borogoves

And the mome raths outgrabe.

In Mandarin it is:

While this sounds almost like the English—if

Jabberwocky can be called English—all the sounds in it are nevertheless

within the phonemic inventory of the initials, finals, and tones of

Mandarin. When spelt in the National Romanization, it even looks like

the English in places:

Yeou 'tian beirlii, nehshie hwojihjide toutz

Tzay weybial jiinj gorng jiinj berl.

Hao nansell a, nehshie borogoutz,

Hair yeou miade rhatz owdegerl.

And later on, when Humpty Dumpty explains

the etymology of the difficult words, it will of course have to come

out right in the translation. For example, 'in the wabe' is translated

as tzay weybial, since just as 'wabe' comes from 'way before,'

'way behind,' and 'way beyond,' so does weybial

come fromjeybial, neybial, and waybial,

that is, 'this side,' 'that side,' and 'outside.'

In connection with the liberty taken

with the original text for reasons of rhythm, length, etc. is it legitimate

to add what was not in the original beyond just some necessary fillings?

For example, to quote from Through the Looking-Glass

again, when the Lion asks whether Alice is animal or vegetable or mineral:

donqwuh, jyrwuh, kuanqwuh (動物, 植物, 礦物) and the Unicorn says she is a monster,

the only natural translation for the word is guaywuh

(怪物), which, though quite literal, is an overtranslation. Again, when

the penultimate stanza in the epilogue:

In a Wonderland they lie,

Dreaming as the days go by,

Dreaming as the summers die:

is translated as:

Beenlai dou sh menqlii you, 本來都是夢裏遊, Menqlii kaishin menqlii chour, 夢裏開心夢裏愁, Menqlii sueyyueh menqlii liou: 夢裏歲月夢裏流:

lines 2 and 3 in the English say the

same thing, while line 2 in the translation which, though it is in the

mood of the poem, has been added rather gratuitously. Perhaps this overtranslation

could compensate a little for the sin of omission in failing to translate

the initial letters in each line of the poem to spell out the name ALICE

LIDDELL.

Finally, a dimension of fidelity of

practical import which has already been touched upon briefly is the

situation of use of the original language and that of the translating

language, and this often involves the interchange of language and non-language.

In translating plays from English into Chinese, I have often met with

cases where dialogue has to be translated as stage direction and vice

versa. There is a Chinese character 唉! which in certain contexts every

reader will pronounce as [ɦai]. Now this involves the use of the 'voiced

h,' a non-existing sound in the normal list of Mandarin phonemes and

is therefore on the borderline of language and non-language. To put

it in English, the usual practice is of course simply to write the word

sigh, which is then translating quasi-language and not ordinary

language. One would then be giving a stage direction in place of giving

a translation of the dialogue. Sometimes, during the act of translating

live speech, the situation itself changes before the translation is

finished. Then what should the translator do? If he finishes the translation,

he will be translating a true sentence into a false sentence. If not,

what? Here is what a resourceful airline pilot did in announcing an

emergency landing, presumably on a transatlantic flight. He starts with

French:

Attention, mesdames et messieurs.

C'est votre commandant. Attachez vos ceintures de sécurité et préparez-vous

pour un atterrissage d'urgence.

Achtung, meine Damen und Herren,

hier spricht ihr Flugzeugführer. Bitte, befestigen Sie ihren Sicherheitsgürtel

und bereiten Sie sich auf einer Notlandung vor.

Ladies

and gentlemen, forget it. Everything is A-OK.[17]

Now is this a translation? And if so,

what is the degree of fidelity?

In

all the preceding discussions about dimensions of fidelity, treating

them as if they were measurable, independent variables, it must be admitted

that they are really neither measurable nor completely independent.

We are far from reaching a workable quantitative definition of any of

the dimensions, not to speak of formulating a mathematical function

with a view to maximize its value.[18] The present state of affairs

is still what in some of the formal disciplines is known as the pre-systematic

stage, which is just another way of saying that the ideas are still

half-baked. We are still not much beyond the stage, as stated by J.

P. Postgate more than fifty years ago: 'By general consent, though

not by universal practice, the prime merit of a translation proper is

Faithfulness, and he is the best translator whose work is nearest to

his original.'[19] But since nearness is a matter of degree, we are

back to the problem of measurement of fidelity-back where we started.

One useful test is to retranslate the translation into the original

language and see if one can find a better fitting equivalent in the

original language. If one can, then the translation is not faithful

enough, as Mark Twain has well demonstrated. This is to be sure only

a testing procedure and the problem of multidimensionality is still

with us. But so far as that is concerned, in what field of inquiry is

one not troubled with the problem of multidimensionality?

Related material from China Heritage Quarterly:

- The Wujing Project—towards a new translation of the Five Classics into the world's major languages

- Lionel Giles: Sinology, Old and New, by John Minford

- Contemplating Reading: Sixteen Views, by Chen Jiru 陳繼儒

Notes:

[1] That is, in so far as pitch characteristics are not a part of the phonemic system of the language being used.

[2] Naoyeuk

in standard Cantonese, but pronounced Niouyoak

in another southern dialect, presumably spoken by the original transliterator

of this name.

[3] 劍

in Cantonese is kimm.

[4] C. J. Catford, A Linguistic

Theory of Translation (Oxford, 1965), p. 66.

[5] Probably not as blunt as 'Old

man!' or as deferential as Legge's 'Venerable sir!'

[6]

Op. cit., pp. 25-26.

[7] A subscribed circle indicates optional

neutral tone, that is, either donq-'

syyle or donq.syyle.

[8]

The Chinese World, San Francisco, February 14, 1968.

[9] The Chinese World,

San Francisco, July 11, 1955.

[10] For details on these terms, see

Y. R. Chao, 'Chinese Terms of Address,' Language

32 (1956).1.217-241.

[11] In my translation of Through

the Looking-Glass, in which the Red Queen objected to Alice's saying

that she had lost her way because all the ways belonged to the queen,

I had of course to render 'her' literally in order to make the point.

[12] For further details, see CYYY

(Ts'ai Yüan-p'ei Commemorative Volume) 1933, p.148. An example of Yiddish

intonation as a grammatical form is found in Catford, p. 54.

[13] To be published, according to

a letter from Mr. Ciardi, in 1968 or 1969.

[14] Saturday Review, October

7, 1961.

[15] Schirmer's Library ed., Vol. 343,

Eng. tr. Th. Baker, 1895, 1923, pp. 214, 228.

[16] Under the title of Tzoou Daw

Jinqtz Lii (走到鏡子裏), it will form Volume II of Readings in Sayable

Chinese (Asian Language Publications, San Francisco, 1968), where

a better version of the following lines can be found on p. 32, lines

1-4 (first stanza) .

[17] From a cartoon in Punch,

October 19, 1966, p. 577.

[18] A beginning in the quantitative

study of quality is found in John B. Carroll's 'An Experiment in Evaluating

the Quality of Translations,' Mechanical Translation and

Computational Linguistics 9.3; 4.55-66 (1966).

[19] J. P. Postgate, Translation and Translations (London, 1922), p. 3.