|

||||||||||

|

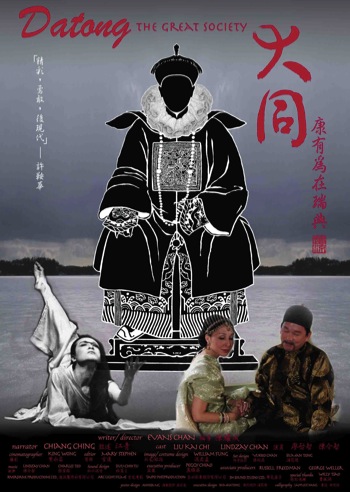

ARTICLESDatong: The Great Society 大同: 康有爲在瑞典 A film by Evans Chan 陳耀成

Director's StatementKang Youwei and his disciple Liang Qichao have been praised by some scholars as the first modern Chinese. The philosopher Li Zehou hailed Kang as the most important modern Chinese philosopher, and Prasenjit Duara has declared Kang to be the one universal thinker that modern China has produced. What is of special interest to me is Kang's visionary tract Datong Shu 大同書, the Book of the Great Way, which was his fervent attempt to revive and update the Confucian utopia for the modern world. In his typology, the world evolves from the Age of Chaos, to the Age of Rising Peace, which is characterized by the accumulation of Small Wealth (xiaokang 小康), or Moderate Prosperity, then to the Age of Great Peace, in which Datong—the Great Way, or the Great Commonwealth—will prevail. As it turned out, xiaokang has been the slogan and the declared objective of Deng Xiaoping's economic liberalization in the 1980s. But this xiaokang phase has produced, over three decades, a more and more painfully polarized nation. Rather than being a nation that enjoys Small Wealth or Moderate Prosperity, China has become a country in which Wealth is concentrated in the hands of a Small elite political class. With the demise of socialist or Marxist ideals, does China's own homegrown millennial utopia stand a chance, or simply deserve, to be revived again in its homeland? I'll answer Yes, without hesitation. Hence the title of this film. An Interview with the DirectorInterviewer: William Cheung GenesisQ:What was the genesis of this film project? EC: The genesis of this film could be dated to my stumbling upon Kang Youwei's newly published Swedish Journals in Hong Kong in 2007, eighty years after his death. It immediately rang a bell, since I had come across a quirky reference to Kang owning a Swedish isle in Jonathan Spence's The Search for Modern China (1991), which I consult from time to time. The Journals were annotated and edited by Göran Malmqvist, a Sinologist and a member of the Swedish Academy, whose Swedish edition of this book was published in the 1970s. Q: Kang Youwei is unquestionably a household name in China, but commonly known only for his crushed Hundred Days reform in 1898, the first serious attempt to modernize dynastic China within the Qing court. What new material about him have you uncovered?  Fig.1 Poster for the film Datong: The Great Society EC: Kang's sojourn in Sweden between 1905 and 1908, where his youngest daughter was born, and the anti-American boycott (1905-1906) he orchestrated overseas for China to thwart the Chinese Exclusion Act, which resulted in his two meetings with President Theodore Roosevelt, are events during his exile that are entirely new to me and, I would say, to most Chinese. Apparently, the collapsed Hundred Days turned Kang into China's first grand traveler of the modern times—partly a result of his intellectual curiosity which aimed at, as he once said, 'sampling different nations like herbs for developing a medicine to heal a sick China', and partly simply because he was a fugitive with a price on his head and assassins on his heels. Kang's attachment to Sweden is palpable in his diary. He was even grateful for the 'misfortune' that led him to the Scandinavian country, and he called the island in Saltsjobaden he lived on 'Shelter Island'. Looking for, and even finding, a home yet missing and agonizing over his original home, lends a unique poignancy to his diary, and profoundly resonates with a global modernity marked by exile, migration, and deracination. NarrativeQ: Datong has a complex narrative strategy. How did you find your approach, especially how Chiang Ching 'entered the picture' with her unusual role as the narrator and partly the subject in this docu-drama? EC: My original plan was to make a straightforward documentary, for which I conducted an interview with choreographer/stage director Chiang Ching, since she is the best known overseas Chinese artist living in Sweden. But after meeting her, realizing that she owns an island herself, and that she herself has had at times a difficult and ambivalent relationship with China, I decided to invite her to narrate the film, weaving her romance with Sweden into Kang's. An intriguing aspect of her narration concerns the fact that Chiang Ching, who is a former actress herself, has the same Chinese name as Jiang Qing—Madame Mao and the head of the Gang of Four, also a former actress. Chiang Ching's family and associates in the PRC all suffered in varying degrees during the Cultural Revolution, partly because of her name. But one suspects that it could also be due to Chiang Ching's stardom in Taiwan in the 60s, where she acted in hit films that are considered metaphorical anti-PRC Cold War narratives. To have the creative and benevolent namesake of Madame Mao retell the tragic impact of Sorrows of the Forbidden City—the film that escalated the Cultural Revolution—is for me an act of, if not redemption, then private prayer. StyleQ: How did you come upon the film's distinctive stylistic approach in relationship to your subject? EC: While developing the project, I realized that Kang's Swedish sojourn could provide a framework for me to reintroduce Kang to the world, and to China, or its official history. And the force of both Kang's and Tung Pih's lives simply cry out for dramatization. Finally, 'Datong: The Great Society' became a docu-drama. Dream Play, the masterpiece by the Swedish playwright, August Strindberg, has always been dear to me. Kang's life brought back memories of the particular scene where one hears the angry outburst about the melancholic fate of people who 'try to improve things'. I then realized that excerpting Dream Play gives me the aesthetic foundation to create the docu-drama through theatrical presentation, while bringing in interviews and vintage footage. The dramaturgical use of ghosts and the danse macabre grew organically as I forged ahead. At some point I realized that such elements were probably nourished as much by Strindberg's plays as by the daunting Ingmar Bergman of The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries—a film I watched repeatedly as I woke up to my love of cinema. Mao, Kang and Sorrows of the Forbidden City (Qinggong mishi 清宫秘史)Q: If Dream Play is important for Datong's aesthetic framework, Sorrows of the Forbidden City is substantially important for the film's content. Can you elaborate on Sorrows' relevance, both aesthetically and politically, to Datong? EC: The Hundred Days reform might be a famous and dramatic episode in early modern Chinese politics, popular film and literature has been drawn to it mostly as part of the melodrama of Empress Dowager Cixi's ruthless climb to, and maintenance of, power. After dethroning Emperor Guangxu, who worked with Kang, she set up, shortly before her death, Puyi as 'the last emperor', who became the subject of the best-known Qing drama biopic, directed by Bertolucci, outside of China.  Fig.2 A still from Datong: The Great Society In fact, director Li Han-hsiang, who launched the narrator of this film, Chiang Ching, into her movie stardom, made a series of Cixi films in the 1970s and 1980s in Hong Kong and the PRC. But the first major film in the Cixi vein was Zhu Shilin's Sorrows of the Forbidden City, which was released in 1948, the year before China's civil war came to an end. As an admirer of the magnificent Zhu Shilin, director of Sorrows, I have published papers on Zhu in general, and Sorrows, which used the Hundred Days reform as its backdrop, in particular. Sorrows is far from Zhu's best film, but its mysterious escalation, in 1967, of the Cultural Revolution, during which it was transformed into a tool to persecute Liu Shaoqi, chairman of State, who was Mao's chief political (and ideological) rival, has always puzzled and intrigued me. My latest research on Kang led me to Kang Tung Pih's commemorative essay about her father, in which she cited Liu Shaoqi's praise of Kang's reform. That coincidence, for me, provided one background detail for the probable initial attention Mao paid to Sorrows or the charge that Liu admired Sorrows. Mao might have been an admirer of Kang and even Tung Pih, yet he unquestioningly viewed Kang as a utopian socialist. Thus, his efforts to 'rectify' Kang and the philosophical and political program Kang represented. Mao's relationship with Kang was further complicated by his use of Kang's Datong Shu in launching the Great Leap Forward campaign, which almost bankrupted his political dominance and ideological mission. Obviously, the ransacking of Kang's grave and Tung Pih's death by medical neglect—also the cause of Liu Shaoqi's death—during the Cultural Revolution were tied up with the fate of Sorrows. Zhu himself died of a stroke the day the Gang of Four's vicious essay—'Sorrows of the Forbidden City is A Traitor's, Not a Patriot's, Film'—appeared in Hong Kong. Since Zhu had used a domestic melodrama genre, in which Kang was relegated to the margin, to anatomize the tragic ending of Hundred Days, I think Kang should re-gain his rightful place, if not actually in the Zhu film, then along side it. That's why Sorrows was excerpted throughout Datong, and there are scenes of Kang playing off the excerpt. Those excerpts are also glimpses into spots that may or may not arouse the kind of accusations Jiang Qing's cohorts leveled at the film. You can say Datong is my postmodern remake of Sorrows of the Forbidden City. Evans ChanThe filmography of Evans Chan (website: www.evanschan.com), New York-based critic, playwright and filmmaker originally from Hong Kong, includes ten narrative and documentary features: To Liv(e) (1991), Crossings, (1994) BauhiniaI (2002), The Map of Sex and Love (2001), The Life and Times of Wu Zhong Xin (2003), Journey to Beijing (1998), Adeus Macau (1999), Makrokosmos I & II (2004), The Maverick Piano (2006), and Sorceress of the New Piano—The Artistry of Margaret Leng Tan. Chan's films have been shown at film festivals in Berlin, Rotterdam, London, Moscow, Montreal, Vancouver, AFI-L.A., Chicago, Seattle, Melbourne, Auckland (New Zealand), Bombay, New Delhi, Hong Kong, and Taipei. William Cheung lectures on Chinese arts and film aesthetics at the General Education Centre, Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Related material from China Heritage Quarterly:

|