|

ARTICLES

An Unexplained Image from the Garden of Perfect Brightness | China Heritage Quarterly

An Unexplained Image from the Garden of Perfect Brightness

Zheng Yangwen 鄭揚文

University of Manchester*

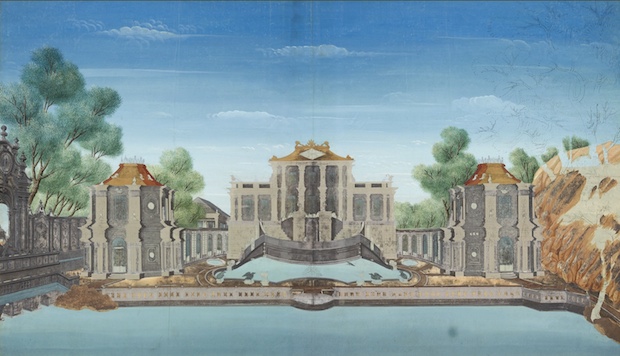

Fig.1 The coloured image from the Manchester edition of the Engraved Views of the Western Palaces in the Garden of Perfect Brightness.Reproduced by courtesy of the University Librarian and Director, the John Rylands University Library, University of Manchester, United Kingdom (Click image to enlarge.)

�

A complete set of the Engraved Views of the Western Palaces in the Garden of Perfect Brightness 圓明園西洋樓銅板畫 is known to include twenty images. Until recently, it was believed that there were only three complete sets to have survived until the present: those at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the Getty Research Institute, and the New York Public Library.[1] The Views were commissioned by the Qianlong emperor in the 1770s and engraved in France the following decade.

In July 2010, I came across the first known full set of Views in the United Kingdom in the John Rylands Library at the University of Manchester. To my surprise, the Manchester set contains an additional watercolour image.[Fig.1] In other words, the John Rylands set has twenty-one images. This coloured plate features jottings at the top and bottom which read: 'Planche 2e qui a été commencée à être mise en couleurs' and 'Planche 2e esquissée pour la couleur'. Whose handwriting was it? The Views are not known for coloured plates. Where did this watercolour come from? Was it ordered by the Qianlong emperor or was it the work of Jesuits in Beijing hoping to please their imperial patron?

Arjun Appadyurai and Igor Kopytoff have observed that '[c]ommodities, like persons, have social lives', their own 'life histories'.[2] Commodities, be they houses or paintings, lead 'lives' independent of their owners. We learn about them by studying their owners and their life histories.[3] What can we learn from social life of the John Rylands set of the Views of the Western Palaces with its enigmatic watercolour plate?

In 1901, Mrs. E.A. Rylands purchased some 8,000 ben of Chinese works, mostly printed between 1550 and 1850, and about 1,000 Chinese illustrations, mostly from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, depicting many aspects of Chinese history and life, from the Bibliotheca Lindesiana, a collection of Oriental material assembled by the twenty-fifth and twenty-sixth Earls of Crawford and Balcarres over the previous half century.[4]

The Crawford Collection, as it came to be known, was built around the valuable Chinese library belonging to Pierre Leopold Van Alstein, auctioned off in Ghent in 1863.[5] Many of the Alstein items came from the collections of pioneering European Sinologists, including Isaac Titsingh, Jean-Pierre Abel-Rémusat, Julius von Klaproth and, in particular, Jean-Pierre Guillaume Pauthier. Lord Lindsay (the twenty-fifth earl) added to his collection during the following decade, purchasing items through Joseph Edkins and Alexander Wylie of the London Missionary Society, and the Parisian publisher and bookseller Benjamin Duprat. These books were examined and collated by John Williams, Secretary of the Royal Astronomical Society, who died in 1874 before he could complete a projected catalogue of the collection.

Aside from Benjamin Duprat and John Williams, all those mentioned above had had much to do with China. Pierre Leopold Van Alstein (1792-1862) was a fervent collector of not just Chinese but also Near Eastern materials, many of which ended up in Manchester via the Bibliotheca Lindesiana. Isaac Titsingh (1745-1812) led the VOC (Dutch India Company) embassy to China in 1795, two years after the British East India Company mission led by Lord McCartney. Unlike the British, Titsingh is said to have performed the kowtow, an act which may well have caused the Qianlong emperor to look at the Dutch in a more favorable light. Jean-Pierre Abel-Rémusat (1788-1832) was one of the earliest Chairs of Chinese Studies at the Collège de France. A German Sinologist, Julius Heinrich Klaproth (1783-1835) accompanied the Russian diplomat Count Yurii Alexandrovich Golovkin (1762–1846) to China in 1805-06. Jean-Pierre Guillaume Pauthier (1801-1873) wrote much about China; his large collection of Chinese works was auctioned off twice and twice Lord Lindsay was there to salvage the best. A missionary-turned-Sinologist who spent nearly fifty-seven years in China, Joseph Edkins (1823-1905) was very much an 'old China hand'. So too was Alexander Wylie (1815-1887), who worked closely with James Legge in Shanghai and accompanied Lord Elgin to Nanjing in 1858, meeting there with Taiping officials. Could any of them have procured the set and had them coloured?

The coloured plate itself yields more information. First of all, a standard set of the Views begins with a depiction of the southern façade of the first European palace built on Chinese soil, the Xie Qi Qu 諧奇趣, which literally translates as 'Harmonious, Exotic, Interesting'. Placing the watercolour over the original copper engraving reveals that the coloured plate is a replica of this pavilion in the Western Palaces. However, the six Chinese characters on the upper right corner of the original—Xie Qi Qu Nanmian Yi 諧奇趣南面一—are missing from the coloured plate. This is because the plate was hand drawn rather than printed, a fact that can also be seen from the sketches on the left-hand side of the image, as well as those on the right-hand side where the colouring on the trees is obviously incomplete. Secondly, although the size of the two plates is similar, the quality of the paper is different: the paper used for the watercolour plate seems to be thinner than that of the original prints made from copper engravings. Thirdly, the colouring itself tells us something important. Contemporary records indicate that although Xie Qi Qu palace was built in the European style, it contained a number of Chinese features, including a yellow roof with blue and green tiles. The coloured plate shows a brown roof.

The binding of the album reveals more. Its dark green Chinoiserie motif cover seems to suggest continental European rather than British binding. The fact that the Bibliotheca Lindesiana crest, which is not as one would expect it to be in the most prominent place on the album, seems to imply that it was bound before Lord Lindsay purchased it in 1863. Most revealing of all, the order in which the prints are bound hints at the possibility that the binder did not read Chinese, as the album starts with the second image of the original copper engravings: Xie Qi Qu Beimian Er 諧奇趣北面二 or 'Northern Façade of Harmonious, Exotic, Interesting, Plate Two', followed by the watercolour plate, and then the Xie Qi Qu Nanmian Yi 諧奇趣南面一 or 'The Southern Façade of Harmonious, Exotic, Interesting, Plate One'. Those mentioned earlier, from Isaac Titsingh to Alexander Wylie, are unlikely to have made this mistake as they all knew Chinese. This makes Benjamin Duprat the most plausible candidate, as he was the only one in the group who did not study Chinese. Said to have assembled the largest collection of oriental books in France at the time, could Duprat have something to do with the colouring and the incorrect binding? The all-blue background, from the sky to the water in the pond, is also striking and puzzling. Why the blue pond?

Further inquiry takes us to the preceding century and the period of the construction of the Western Palaces themselves. Of the hundreds of Jesuits who served in China there were only three or four who were involved in the design of the European palaces. These were Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766), Jean Denis Attiret (1702-1768) and Ignace Sichelbart (1708-1780), described by one observer as '[les] trois peintres les plus chers a K'ien-long'.[6] Jean Damascine Sallusti (d.1781), an Augustinian, was also involved in work on the palaces, but he was best known for his work on the battle scene engravings. Although they helped design the European palaces, all of the above-mentioned painter-missionaries died before the copper engravings were made. Is it possible that the water colour plate was the very first design sample furnished to the Qianlong emperor by these 'trois peintres'? Two other Jesuits, Michel Benoist (1715-1774) and Francois Bourgeois (1723-1792), oversaw the construction of the water fountains, but neither were painters. Even if they had the capacity to produce such an image, the coloured plate does not feature their works—the water fountains which were Qianlong's obsession—at all. What about those other missionaries who repaired clocks, made instruments, and waited on and translated for Qianlong as they competed with each other to gain the favour of China's Sun King?

Fig.2 The Xie Qi Qu viewed from the south, March 2012 (Photograph: Daniel Sanderson)

Let us not forget a most colourful character—the last important Jesuit on Chinese soil—Jean-Joseph-Marie Amiot (1718-1793) who was favoured by the Qianlong emperor and showered with gifts and privileges. Amiot carried on a life-long correspondence with one of Louis XV's favourite ministers, Henri-Leonard Bertin (1720–1792), supplying him with information about and materials from the Qing court.[7] 'Dans ce précieux dépôt sont représentés avec une curieuse exactitude les temples, palais, maisons de plaisance, serres chaudes, fourneaux, tombeaux, arcs de triomphe et autres ouvrages de l'architecture chinoise; paysages, l'endroit dit Versailles de Pékin...'[8] Could Amiot have coloured the plate in his endeavour to please the aging Qianlong emperor? Was he responsible for procuring this set [for whom?], given his power and connections at the time [in China or France?]? Let us not forget the artists involved in the production of the Views: the eminent French engraver Charles-Nicolas Cochin (1715-1790), his peers, the Aliamet brothers who operated in both France and Germany, and above all Jacques-Philippe Le Bas (1707-1783), engraver to the 'Cabinet du roi'.

It seems strange that tracing the social life of this unusual set of the Views of the Western Palaces leads us to an exclusive cast of European characters. The Manchester set, with its unique watercolour plate, appears to have more to do with the Jesuit Mission to China, Louis XV and his ministers, European merchants, diplomats, engravers and booksellers, and British Protestant missionaries and philanthropists, than with China itself or any Chinese individual. This inscrutable object, in other words, provides an opportunity to study Chinese history from a new perspective, through a European 'lens'. At the very least, the blue-dominated watercolour with its blue pond in pride of place is the best testimony to my argument that China was not a 'Walled Kingdom'.[9] It was the seas that made the eighteenth century imperial China's 'last golden age'.[10] She reached out to the maritime world far more actively than historians have traditionally allowed, while the seas and what came from the seas shaped her history, culture and identity. China's multifarious role in global history is still waiting to be researched and written.

Zheng Yangwen (PhD Cambridge) is Senior Lecturer at the University of Manchester. She is the author of The Social Life of Opium in China, which has been translated into Italian and Korean, and China on the Sea: How the Maritime World Shaped Modern China. She is also the editor of Negotiating Asymmetry: China's Place in Asia (with Anthony Reid), The Body in Asia (with Bryan S. Turner), Personal Names in Asia: History, Culture and Identity (with Charles J-H Macdonald), and The Cold War in Asia: the Battle for Hearts and Minds (with Hong Liu and Michael Szonyi). She is currently writing Choreographing History: the Revolutionary Model Play 'Red Girls Army' and editing China Surreal: from the Jesuits to Zhang Yimou for publication.

Notes:

*I am grateful to John Hodgson, Collections and Research Support Manager (Manuscripts and Archives) of the John Rylands Library, who helped me with the provenance of the Chinese collection, this set of prints in particular, and shared with me his unfinished article 'Modern Medici: the 25th and 26th Earls of Crawford and their Manuscript Collections' which enabled me to write this piece.

[1] The Victoria and Albert Museum in London has a few images of the set, but not a complete set.

[2] Arjun Appadurai, 1986, 'Introduction: commodities and the politics of value' and Igor Kopytoff, 'The cultural biography of things: commoditization as process', in Arjun Appadurai, ed., The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), pp.3-63 & 64-91.

[3] Zheng Yangwen, The Social Life of Opium in China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), p. 1.

[4] Alexander William Crawford Lindsay, 25th Earl of Crawford, 8th Earl of Balcarres, 1812-1880, was a Scottish peer, art historian and collector. James Ludovic Lindsay, 26th Earl of Crawford and 9th Earl of Balcarres, 1847-1913, was a British astronomer, politician, bibliophile and philatelist.

[5] This album is not at all what the Chinese Collection at the Rylands has to offer. It contains the complete first edition of Kangxi Dictionary, a prayer book written in Chinese by the Jesuit Nicolas Longobardi for the Shunzhi Emperor, and many more rare books and manuscripts. 28 items are dated before 1600.

[6] Louis Pfister, Notices Biographiques et Biblographiques sur les Jesuites de l'Ancinne Mission de Chine 1552 – 1773 (2 tome. Chang-hai: Imprimerie de la mission Catholique, 1932), Tome II, p. 831.

[7] Gwynne Lewis, 'Henri-Leonard Bertin and the Fate of the Bourbon Monarchy: the 'Chinese Connection'', in Malcolm Crook, et al, eds., Enlightenment and Revolution: Essays in Honour of Norman Hampson (Aldershot [England] & Burlington [Vermont]: Ashgate, 2004), pp. 69-90.

[8] Louis Pfister, Notices Biographiques et Biblographiques sur les Jesuites de l'Ancinne Mission de Chine 1552 – 1773 (2 tome. Chang-hai: Imprimerie de la mission Catholique, 1932), Tome II, p. 852.

[9] Zheng Yangwen, China on the Sea: How the Maritime World Shaped Modern China (Boston and Leiden: Brill, 2011).

[10] Charles Hucker, China's Imperial Past: an Introduction to Chinese History and Culture (London: Duckworth, 1975), p. 296.

|