|

||||||||||

|

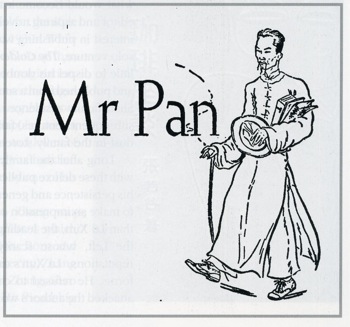

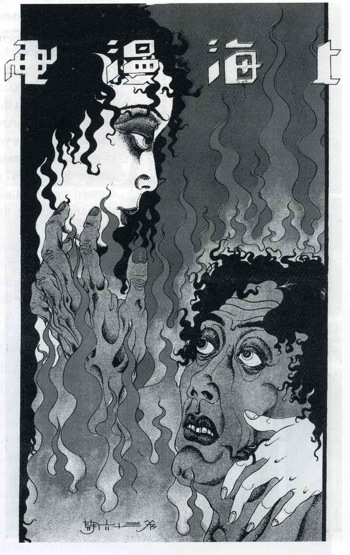

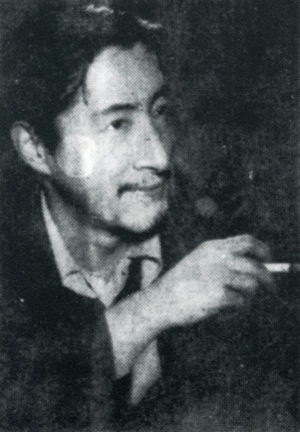

FEATURESMonstre Sacré: The Decadent World of Sinmay Zau 邵洵美Jonathan Hutt[1]Succès de Scandale: the Birth of a Chinese VerlaineIn 1936, the up-and-coming artist, Lu Shaofei 魯少飛 contributed a sketch to the inaugural issue of a new cultural journal, Six Arts (Liu yi 六藝), entitled ‘Portrait of a Literary Gathering’ (Wentan chahua tu 文壇茶話圖).[2]  Fig.1 Lu Shaofei, 'Portrait of a Literary Gathering,' Six Arts (Liu Yi), vol.1 no.1 (15 February 1936), p.8

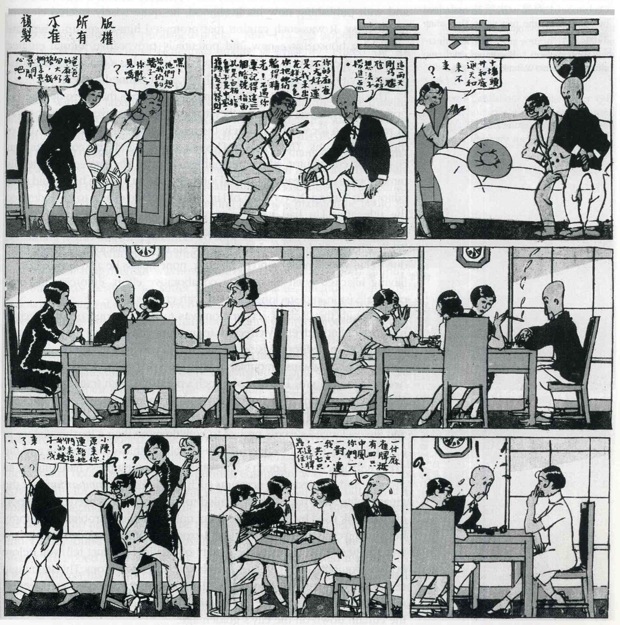

The cartoon depicted an imaginary meeting of China’s literary élite, bringing together in one room authors responsible for some of the most innovative works to emerge since the New Culture movement. At first glance, this drawing might easily be mistaken for the type of self-aggrandising exercise common amongst China’s notoriously egotistical men of letters. In fact, quite the reverse is true. Lu’s illustration is a cutting parody of the heavyweights on the Chinese literary scene, offering an insider’s look at the jealousies, naked animosity, and ideological warfare that were then prevalent. The artist’s mischievous seating plan plays up these divisions, placing sworn enemies side by side, bringing tensions dangerously close to boiling point. These tortuous interpersonal relationships are now well documented, but sadly, the man Lu selected as host and charged with maintaining this fragile peace remains virtually unknown today. And yet he was an individual blessed with the unique ability to transcend factional boundaries, a man who consorted with left-wing dramatists and apolitical humorists alike; a one time pin-up boy of Shanghai’s Francophiles, he shared the back of his limousine with such notable literary figures as Lu Xun 鲁迅 and his literary merits were endorsed by the noted romantic poet Xu Zhimo 徐志摩. This extraordinary individual was Shao Xunmei (邵洵美, 1906-1968). By 1936, Shao’s star was waning. His latest collection of poems, due to be published that year, would fail to cause a ripple. His extensive publishing interests, meanwhile, were proving to be a financial disaster, forcing him to produce pulp fiction in order to cover his mounting debts. If Shao’s name was mentioned it was more likely in reference to his scandalous love life than his literary prowess. At the age of thirty, Shao was close to becoming a has-been. How then did he warrant inclusion in this visual Who’s Who of the literary beau monde? Was this simply Lu’s gesture of gratitude for Shao’s support early in his career? If his position centre stage seems somewhat tenuous, this would certainly not have been the case a decade earlier. Then, at the tender age of 21, he made a sensational debut with the publication of his first collection of decadence-infused poetry. But his celebrity was not confined to Baudelarian chic. Undoubtedly his social pre-eminence owed more to his personality and lifestyle than to his ‘immoral’ verse. Aristocrat, millionaire, collector, playboy, socialite, dandy and businessman; Shao’s numerous personae speak volumes on the true nature of literary fame in Republican Shanghai. Consequently, Shao’s Belle Époque coincided with the golden age of China’s first great metropolis. He was not simply a product of this city and a reflection of its aspirations; he was ultimately also a victim of its fickleness.  Fig.2 Portrait of Shao by Xu Beihong Yet Shao’s remarkable rise and fall was only one aspect of an extraordinary life. I would argue that of his generation Shao was the greatest representative of the Shanghai Style for, like the city in which was born, he too would generate extremes of emotion. For some, he signalled the dawn of a long-awaited intellectual golden age in which the city’s cultural sphere would take its place alongside other great civilisations in world history, while for those appalled and intimidated by Shanghai’s reckless transformation he was the embodiment of the city’s excess and its pretensions. Furthermore, as the city’s ambassador, Shao’s fate became inextricably linked to that of the city both in his own lifetime and as a highly problematic historical figure. Even with his partial rehabilitation in the 1990s, Shao would remain a caricature. It is a symbol of his fall that his position on this new cultural hierarchy is far below that of many he had once puzzled and astounded with his precocious talent, grand ambitions, and lust for life. The gates of Heaven have swung open, O Lord, I am not one to enter. I have found comfort in hell, I have already dreamed of awakening, In the short night. —‘May’ 五月 from Paradise and May.[3] ‘China has a new poet, its very own Verlaine’ —Xu Zhimo on Shao Xunmei[4] Despite eventually falling foul of literary fashions, at one point Shao’s poetry had generated effusive praise from his peers. None was apparently greater than the glowing endorsement from China’s first modern celebrity poet, Xu Zhimo, following the publication in 1927 of Shao’s poetry collection, Paradise and May. Comparison to the French poète maudit was high praise indeed, considering that for several years the Chinese literati had displayed an almost unhealthy fixation with the cultural heroes and literary ‘isms’ of nineteenth-century France. This idolatry was at its most extreme in the salon of Shanghai’s Francophiles where in the late 1920s Zeng Pu 曾樸 and his son, Xubai indulged in playing the roles of Dumas père et fils, entertaining the Chinese equivalents of Loti, Flaubert, and France. Therefore it is little wonder that many of the accolades for Shao were voiced by those at the centre of the city’s Francophile circle and in particular its self-appointed spokesman, Zhang Ruogu 張若谷. Unlike Xu, Zhang detected within Shao’s verse the traces of a literary giant other than Verlaine, one whose prestige extended far beyond the confines of the Francophile set. Venerated by members of such diverse literary groupings as the Crescent Moon School (Xinyue pai 新月派) and the pre-Marxist Creation society, Baudelaire was considered to be the zenith of literary chic in Chinese literary circles and accordingly Zhang’s comparison between Shao and this great sage of the modern era surpassed even Xu’s generous commendation.[5] For Zhang, Shao resembled his illustrious predecessor in his ability to capture the poetic beauty of a daemonic universe characterised by all manner of ‘grotesque, sinister, melancholic, and shadowy phenomena, a world of opium-induced inebriation, morbid desires, and man-made stimulation, a pathway to the lascivious and barbarous realm of imagination.’[6] Ah, flesh perfumes the season’s blossoms, The silent rain harbours obscene desires, Consumed by hatred for these physical evils, Ah, what will wash away this scarlet stain? —‘Spring’ 春 from Paradise and May[7] Zhang attributed the decadent overtones of Shao’s verse to the author’s loss of ‘faith’ and his apparent expulsion from ‘paradise’, a term which for Zhang (an ardent Catholic and inheritor of the French literary spirit) possessed both great religious and Romantic significance. Hence, the works of this young prodigy were to be read as the laments of ‘a young flower mourning the loss of the twenty-one petals plucked by the hands of time’.[8] Clearly, Shao’s debut was timed perfectly, for this was the era in which the prime literary value was ‘neither the expertise of craftsmanship nor the vigour or exuberance of creative imagination but rather the intensity of the author’s own emotional experience.’[9] Consequently, the extravagant passions contained in these thirty-three poems were difficult to ignore. For the likes of Xu and Zhang, this voluptuous yet perverse sensibility suggested the dawn of a Chinese Décadisme. It was the realisation of the Shanghai intellectuals’ strenuous efforts to absorb the great artistic spirit of France, signalling the completion of their exotic journey from de Musset to des Esseintes, Baudelaire to Baju, from mal du siècle to fin de siècle. Such acclamation was not simply affirmation of Shao’s talent, but also a vote of confidence in the city itself. For the pro-urban intellectuals there was ample evidence to suggest that Shanghai was entering an exciting period of its development. In the years ahead, they would rhapsodise over this new landscape of skyscrapers, parks, cafés, and cinemas, in the process creating one of the most enduring sobriquets associated with the city, ‘Paris of the Orient’. There was also a sincere belief that through their literary endeavours they would affect the transformation of this city into a new cultural capital modelled on a nineteenth century European prototype. Shao became an icon precisely because he seemed to exude the very sophistication so desperately required by this metropolis in the making. Even to the most urbane of his peers, there was something terribly alien about Shao’s verse with its references to pagan poets and Christian deities, its sexually explicit metaphors and preoccupation with sin. Quiet, quiet, dark night comes again, She wears the grey habit of a nun, Embracing melancholy and sorrow; She is the executioner of light. … … Here is a garden of yesterday, Green leaves have yellowed, Fresh flowers withered, Lively birds have died. As Leo Ou-fan Lee has demonstrated, when writing his modern vernacular verse Shao employed many clichés common in classical Chinese poetry, from the ‘flower-and grass trope’ to the depiction of sex ‘in the image of the coupling of clouds’.[14] Yet, he also acknowledges that the power and notoriety of Shao’s verse rested upon the poet’s ability to infuse such standard imagery with a ‘voluptuous blasphemy’. It was this talent to weave ‘natural objects into an artificial world of sensuality’ that so attracted his peers.[15] Shao’s decadent imagination was the natural union of the classical and the modern, the Chinese and the foreign; it was a new poetic landscape at once familiar yet redolent with the atmosphere and mythological aura of foreign lands.[16]  Fig.3 Bust of Shao by Jiang Xiaojian [Source: Shanghai Sketch (Shanghai Manhua), no.51 (13 April 1929)] Yet, this exotisme was not limited to Shao’s creative imagination; it appeared to be an integral aspect of his personality. For many, Shao was not simply inspired by the Occident but rather was of it, prompting one commentator to classify him as a ‘foreign poet’. As if to vindicate this claim, many physical descriptions of the dashing young poet focused upon what was surely his most Western feature, namely his large nose. Scrutinising him I saw a thin, narrow face, which set off his prominent nose, surely his most distinguishing feature. Above his lips there is a slight moustache and on his cheeks the light stubble of a beard. His long jet-black hair was uncombed but cascaded neatly across his forehead. His brilliant eyes resembled two black grapes on a white jade platter, while the hair falling down over his ears served as a frame for his exquisite features…[17] It was only to be expected that a man compared to a ‘classical male beauty of Ancient Greece’ should have found inspiration in the birthplace of Western civilisation.[18] Coming ashore at Napoli, I went to the museum where I was stopped in my tracks by the mystic beauty of a fresco depicting the Greek poetess Sappho. I searched and searched until I found a copy of her poems in English, and reading them I felt that in many respects they were similar to classical Chinese poems. For someone of such a weak spirit, this was truly an amazing discovery.[19] In the years ahead, Sappho would become a major motif in the works of the young poet. Other than essays designed to introduce the life and works of the Greek poetess to the Chinese reading public, Shao also translated many of her works, including his personal favourite, ‘Ode to the Goddess of Love’. The influence of her poetry on his own works was no less significant, for he was deeply attracted to the melodic metre of her verse, her fiery passions and the purity of such emotions which Shao pronounced eternal.[20] Shao’s epiphany in Naples occurred in 1923 at the beginning of his journey to Europe. He was just seventeen years old at the time. By the end of this four-year odyssey, which included stints at Cambridge and the École des Beaux Arts in Paris, Shao had completed what would become Paradise and May. Here, the reader could follow on the page the author’s peregrinations with each poem completed in some new and exciting locale; ‘Paris, London…drifting on the Red Sea, the Mediterranean, the China Sea, the Indian Ocean, alongside his male and female classmates at Cambridge University, on a visit to the MUSEN DE LOUVRE [sic]…’[21] But this foreign sojourn, an experience he shared with many of his generation, was not sufficient to single him out from his peers. Nor were the poems’ stylistic borrowings, for what could be more common than to imitate a foreign literary figure currently in vogue? What truly separated Shao from his contemporaries was his complete ignorance of the Chinese literary scene. My new poetry wasn’t inspired by anyone. Only much later did I even read Hu Shi’s Experiments. At school I used to read a lot of foreign poetry, which I translated into vernacular Chinese.. Even the name of Xu Zhimo, the greatest of all the new poets, meant nothing to me. My appallingly deficient general knowledge seems rather comical now. But, all the same, it was precisely because of this that my poetry was never exposed to any bad influence.[22] For his admirers, Shao’s literary persona was unique. Conceived in a vacuum, fed on a diet of foreign verse, then brought to life under a Mediterranean sun, Shao served as their bridge to the alien cultural traditions and literary deities they so revered. It is likely that Xu Zhimo intended the comparison with the godfather of the French Decadence to serve as a marker of the artistic terrain rather than a comment on any stylistic resemblance. As a future patron and fellow Anglophile, Xu knew full well that Shao’s foremost literary model originated on the other side of the English Channel. The route my poetry has taken is truly peculiar. From Sappho I uncovered her acolyte, Swinburne; and through Swinburne I became aware of the works of the Pre-Raphaelite school. From there I came in contact with the works of Baudelaire and Verlaine.[23] If Shao’s discovery of Sappho was a decidedly mystical experience, then his discovery of Swinburne should be considered his intellectual awakening. Fittingly, this momentous event occurred during his time at Cambridge. It was following a conversation with the Reverend A.C. Moule (with whom Shao lodged) during which they discussed his discovery of Sappho that the budding poet gained an introduction to Moule’s friend and colleague, J.C. Edmonds, a professor of Greek literature at Jesus College. The encouragement Shao received from Edmonds was critical to Shao’s development as a poet, for not only did Edmonds encourage the young scholar to translate Sappho’s work into Chinese, he also introduced Shao to the works of Swinburne. This chance encounter was to shape Shao’s obsessions and enthusiasms for the rest of his brief, yet dramatic, poetic career. Within these scandalous and revolutionary works, Shao would discover a kindred spirit, an artistic model, and the final member of his literary trinity. You are Sappho’s brother, so am I, Our parents are the Gods who made Venus, The sunset, the rainbow, the peacock’s tail, the feather of the phoenix, The birth of all beauties are their—our parents’—genius. For the Shanghai intellectual of the late 1920s there was much to find attractive in Swinburne’s life. This one figure exemplified the revolutionary spirit rebelling against all autocratic political systems and moral hypocrisy. He was a romantic figure whose acute understanding of the human condition drove him to drink, and a notorious man of letters whose works could cause a public outcry yet influence an entire generation. It was only to be expected that Swinburne would become a pivotal figure not simply in Shao’s poetic career but also in the construction of his literary persona.[25]  Fig.4 The Republican fascination with decadence extended beyond the literary world to the visual arts. The preoccupation with the femme fatale and the end of civilization would soon become major motifs used by Shanghai artists in their portrayal of the city as an urban dystopia. [Source: Shanghai Sketch, no.62 (9 June 1929)] To Shao, like so many English schoolboys before him, Swinburne promised a new wisdom. This wisdom was to be found in the titillating world of sin, perversity, corruption and exquisite refinement; in short, the ‘dangerous’ world of Baudelaire. In 1928, Shao published what can be regarded as the closest thing to a Chinese manifesto of decadence, its title inspired by a Swinburne poem. Fire and Flesh (Huo yu rou 火與肉) was printed in a suitably elegant edition by his own Golden Chamber publishing house.[26] A surprising omission from this panegyric, which included essays on Sappho, Swinburne, Verlaine and George Moore, was Baudelaire. Yet, while he failed to complete his essay on this literary icon in time for inclusion in this collection, Shao accorded him the ultimate compliment when a revised edition of Paradise and May appeared that year under the title Flower-like Evil (Hua yibande zui’e 花一般的罪惡), an homage to Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal.[27] In Shao’s eyes at least, Swinburne and Baudelaire were artistic equals. Both Poems and Ballads (1866) and Les Fleurs du Mal (1857) were for him works of genius capable of ‘liberating a culture imprisoned by religious, ethical and social mores’.[28] Yet for Shao, the poetic truths derived from this descent into moral turpitude had a decidedly Anglo-Saxon slant. The metaphysical inquiry of Baudelaire was secondary to the cult of artifice and the concomitant artistic snobbery of the ultraraffiné intellectual. The Swinburnean variety of decadence therefore offered intoxication but demanded only the pretence of extremity. As Christopher Isherwood recalls, the spiritual descendants of Swinburne were alive and well at Cambridge in the early 1920s when undergraduates armed with Baudelaire unlocked a world of ‘...l’affreuse Juive (the ugly Jewess), opium, absinthe, negresses, Lesbos and the metamorphoses of the Vampire. Sexual love was the torture chamber, the loathsome charnel-house, the bottomless abyss. The one valid sexual pleasure was to be found in the consciousness of doing evil…’[29] This affectation of immorality was obviously the perfect vehicle for expressing adolescent angst.[30] Just as Swinburne’s verse reveals a preoccupation with de Sade, masochism and the femme fatale, so Shao’s poetry displayed a pubescent fixation with ‘wet, soft flesh’, serpents and deflowered virgins. From a flower bed, amidst fragrances you are awake, A virgin’s naked body, a bright moon it does make— I see again your fire-red flesh and skin, Like a rose, opening for my heart’s sake. —‘To Sappho’ 莎佛 from Paradise and May[31] Clearly, Shao represented the very antithesis of the frustrated and sexually dysfunctional intellectual, an image propagated in the highly successful fiction of Yu Dafu. Wealthy, good-looking and with a ‘trophy’ wife (his childhood sweetheart, Sheng Peiyu 盛佩玉, whom he married in December 1927), Shao was free to revel in his sexual awakening, taking his verse into uncharted territory and setting himself on a collision course with the moral majority. Shao’s Swinburnean pose was certainly a success judging by the public response to Flower-like Evil, which echoed the reception of Swinburne’s own Poems and Ballads. Robert Buchanan and John Morley were some of the many critics who had publicly castigated Swinburne for writing verse they considered to be unclean, morbid and sensual.[35] Shao too, now found himself under attack from intellectuals across the political divide. A major criticism was that these works seemed unnecessarily obscure, ‘an assemblage of sensual words—fire, flesh, kiss, poison, rose, virgin—devoid of meaning altogether’.[36] This very incomprehensibility only confirmed the opinion that many Chinese poets, specifically those of the Crescent Moon school, were engaged in slavish imitation of Western poetic forms.

They [Crescent Moon poets] are deeply influenced by the English tradition, not only in their experiments with English poetic forms, but in modelling their works on modern English verse. Liang Shiqiu has said that these experiments attempted to create foreign verse using the Chinese language, infusing them with a distinctly foreign flavour. However, while this was not their intention, in their efforts to create a new Chinese poetry, they unwittingly wrote foreign style verse.[37] Still more of his contemporaries took issue with his overwhelming aestheticism which they believed harboured immoral and blatantly pornographic sentiments. Such a reaction was only to be expected for, as Michelle Yeh has noted, even the more benign concept of ideal love found in the poetry of Xu Zhimo and Zhu Xiang 朱湘 remained controversial, representing both a radical departure from the Chinese poetic tradition and a rejection of orthodox Confucian ethics.[38] Zhu Ziqing, one of the earliest exponents of vernacular poetry and himself the author of sentimental verse, had previously pointed to the problematic nature of this new romantic verse, ‘The theme of ‘ideal love’ is truly a new creation in Chinese poetry; it is unfamiliar to the average reader. The average reader finds it easy to understand empirical love, but ideal love requires contemplation.’[39] Despite the scandalous nature of his work, Shao seemed ill-prepared for the barrage of verbal critiques that greeted the publication of his first two anthologies, but nonetheless lashed out in print. Adopting a suitably lofty tone, he attacked his detractors as poorly–read and emotionally deficient, stating that their remarks said more about their own unpleasant natures than about the work itself.[40] In response to charges of immorality, Shao drew upon his earlier defence of Swinburne: ‘...poetry is poetry, and people are people and it doesn’t do to confuse the two. Someone who writes immoral poetry is not necessarily immoral, while on the other hand the author of moral verse is not necessarily blessed with the same moral qualities. Attempting to determine a poet’s moral character from his verse is simply preposterous.’[41] The Nietzschean quality of genius that Shao identified in Swinburne’s disregard for moral norms was obviously designed to protect his disciple from similar attacks. For a writer blessed with the ability to appreciate the beauty of both the Virgin Mary and the harlot Salome, the misreading of beauty as pornography was somewhat comic.[42]  Fig.5 Cartoon of Shao by the Mexican painter and illustrator Miguel Covarrubias (1904-57). Covarrubias achieved fame as a stage designer and as a contributor of drawings and caricatures for such prestigious publications as the New Yorker and Vanity Fair. This preoccupation with beauty ensured that Shao would henceforth be associated with a motley collection of aesthetes, dandies and Anglophiles. Yet surface similarities aside, Shao shared little in common with the likes of Li Jinfa 李金髮 or Liang Shiqiu 梁實秋. Ironically, it was the arch-enemy of the Shanghai literati, Shen Congwen 沈從文, discussed at length in the first two chapters of this work, who pinpointed the underlying principle of Shao’s verse: ‘His poems are created from the emotional odes to the senses. They are in praise of beauty, and expressions of the hedonistic pleasures found within this aestheticism.’[43] Shao shared Shen’s assessment of his work, identifying himself like Verlaine before him as a hedonist rather than decadent or simply an aesthete.[44] As Leo Ou-fan Lee demonstrates, Shao’s predisposition towards hedonism was tempered by the Chinese intellectuals’ own understanding of decadence. Paradoxically whilst many praised Baudelaire, few if any could identify with his critique of modernity which ran counter to their own unshakable faith in the notion of progress. The solution, as formulated by Xu Zhimo, China’s earliest advocate of Baudelaire, was an extravagant perspective on his works that enhanced the original with layers of theatricality, artful alienation and role-play. In short, a vision of Baudelaire heralded by Gautier and one that was firmly entrenched in European literary circles by the beginning of the Yellow Nineties. As the success of Shao demonstrates, aesthetic hedonism rather than Baudelaire’s nihilism was more in tune with the intellectual tastes of late 1920s Shanghai.[45] More importantly, if hedonism as Shao himself suggests is the most extreme form of individualism, then it was this trait that helped stamp his personality on what might otherwise be considered more highly derivative verse. Hedonism alone, however, does not explain the success of Shao’s Swinburnean pose. Others had attempted similar feats (most notably Wang Duqing’s 王敦慶 claim to be the Chinese Byron) only to be met with ridicule. Shao’s épater les bourgeoisie sensibility worked precisely because he was of neither bourgeois nor peasant stock. As Zhang Ruogu wrote in his introductory essay on Shao, he was ‘...the young master who lives peacefully in his ivory tower. His is a life of leisure. He is a “prince of pleasure” who enjoys both high position and creature comforts.’[46] This aristocratic lineage was to lend his poetry a certain degree of legitimacy. It also informed the complex relationship with his peers whose feelings ranged from admiration and envy to violent hatred. From the outset, many of Shao’s earliest collaborators were sceptical about his commitment to the world of letters. If Shao’s radical verse prompted such reservations, they were merely confirmed by his involvement with a series of self-funded and opulent publications. Shao’s foray into the cut-throat world of Shanghai publishing began with the literary journal Sphinx (Shihou 狮吼).[47] Acquiring a copy of the now defunct magazine in Singapore, Shao was deeply impressed by its heavy ‘art for art’s sake’ bias and Beardsley-inspired illustrations by Lu Shihou 盧世侯 which appealed to his own fin de siècle tastes. Once back in Shanghai, he quickly volunteered his services and, in all likelihood, substantial capital investment, which resulted in the journal’s rebirth. Shao’s albeit brief involvement with this publication was significant both on a personal and professional level for he subsequently developed a close friendship with the his co-editor Teng Gu 滕固, and established a ten-year working relationship with another of the magazine’s editors, the aspiring novelist Zhang Kebiao 章克標.[48] Initially, Zhang also believed this interest in publishing was little more than a rich man’s folly and Shao’s first solo venture, The Golden Chamber Monthly (Jinwu Yuekan 金屋月刊), did little to dispel his doubts. It was modelled upon the notorious Yellow Book and published from a small but lavishly decorated office directly opposite the Shao family residence. Like many publications of the era both Sphinx and The Golden Chamber Monthly displayed the highly eclectic tastes of its contributors, publishing translations and articles on a wide range of Western authors from Dante and Shakespeare to more contemporary figures like Thomas Hardy and Katherine Mansfield. Nevertheless, Shao’s personal tastes were clearly visible in the journals’ preoccupation with the works of the Pre-Raphaelite school (specifically D.G. Rossetti) and ambassadors of English fin de siècle from Walter Pater to Oscar Wilde and George Moore. Sphinx was also the publication in which Shao was to publish his first attempt at fiction, the short story ‘Moving House’ (Banjia 搬家).[49] Like his poetic debut, this work was a revelation to his like-minded peers. Amongst those to heap praise on his prose were Ye Qiuyuan 葉秋原, who proclaimed ‘Moving House’ as ‘the dawn of a new era in China fiction’. Ye pleaded with Shao to devote more of his considerable energies to such creative endeavours as he believed fiction rather than verse was ‘the best medium through which to express your genius’.[50] Another notable member of this chorus was the celebrated novelist Yu Dafu 郁達夫 who praised Shao’s elegant prose style which he compared with that of Shao’s literary idol George Moore.[51] In spite of these glowing testimonials, the erudite and specialised nature of these publications meant that even with a print-run of two thousand, these journals (like many subsequent ventures) failed to sell and years later unsold copies still gathered dust in the family storehouse.[52] The commercial failure of these ventures was no great tragedy to Shao who, as a man of independent means, always considered such projects labours of love and not a source of much-needed income. However, long after the family fortune had evaporated, Shao would still be associated with these deluxe publications and cursed by the epithet of tycoon. If his persistence and generosity eventually won over many sceptics and potential enemies, Shao failed to make an impression on his most powerful adversary. This was none other than Lu Xun, the leading writer of the New Culture movement and icon of the Left, whose scarifying essays were capable of destroying literary reputations. Lu Xun’s campaign against the ‘self-declared poet’ took many forms. He refused to contribute to any journal edited by Shao and attacked the author’s work both in his personal correspondence and in print.[53] There is a saying: ‘to make one’s way in the literary world one requires a wealthy wife, an inheritance, and no fear of legal action.’….Best of all, a rich wife with even richer parents. That way you can use the dowry as literary capital…take the pampered son-in-law who, belittled by the family, enters the literary world with a great reputation…studying portraits of Oscar Wilde, with his button-hole, his ivory -topped cane, he is such a vision… The old adage ‘within the pages one finds one’s very own golden chamber’ now reads, ‘amidst the money one finds a littérateur’.[54] To suggest that Shao purchased fame was unpleasant, but to imply that the money used to scale the literary heights was not, in fact, his own was downright catty. But for Lu Xun, Shao was little more than the ‘pampered son-in-law’ (fujia zhuixu 富家贅婿), implying that his marriage to Sheng Peiyu, the granddaughter of Shanghai’s wealthiest man, Sheng Xuanhuai 盛宣懷 had helped him bankroll his literary career. In many senses, Shao courted such criticism through his often extravagant and always public lifestyle. The image of the struggling author living in his cramped attic had reached almost mythic proportions, and Shao’s lifestyle was completely detached from the day-to-day reality of his fellow Shanghai literati. But if Shao’s sumptuous poetry and self-funded publishing enterprises may have been deemed unfashionable on both aesthetic and political grounds, his way of life remained fascinating even to his natural enemies. Épater les bourgeoisie: the making of a Shanghai rake[55]In one of the many fictionalised accounts of her relationship with Shao Xunmei, the American journalist and author, Emily Hahn, writes of how Shao’s father once ‘tried to buy a rather small white elephant from a visiting circus to give to Heh-ven (Xunmei), who was then four years old’.[56] While this somewhat romantic tale was designed to conjure up the exotic Orient for the readers of The New Yorker, it is nonetheless indicative of Shao’s privileged and somewhat unconventional upbringing. By the time of Xunmei’s birth in 1906, the Shao clan was considered one of the city’s best families. They were traditional gentry whose family seat remained the town of Yuyao 餘姚 in neighbouring Zhejiang province.[57] The family could also boast of having several generations of distinguished service in officialdom to their credit. It was his grandfather, Shao Youlian 邵友濂, who moved the family to the booming treaty port. Once a Qing envoy to Tsarist Russia, Youlian now set about forging strong alliances with two of the greatest merchant-gentry families the city has ever known. For his eldest son, he arranged a suitable match with the daughter of the city’s foremost statesman and powerbroker, Li Hongzhang 李鴻章. Shortly after, his younger son, Shao Heng 邵恆 married into the family of the wealthy industrialist Sheng Xuanhuai. Born Shao Yunlong 邵雲龍 (yunlong, ‘dragon in the skies’), Xunmei was the eldest of Shao Heng’s seven children. Living in the family’s large estate on Bubbling Well Road 靜安寺路, the city’s most exclusive residential address, the young master enjoyed the best of all worlds, a large staff of domestics to cater to his every whim and the luxury of a private education.[58] Only when his uncle died without an heir did Shao stand to inherit the family’s considerable assets. Yet even without this elevation in rank, Shao might have expected a life free of financial worry. Instead, as head of the family, he was to witness this fortune all but disappear in the space of a few short but tumultuous years. Still, such tragedy was unforeseeable and, to his adoring family, the prospects for their golden child seemed particularly bright. He would read political economy at Cambridge, return to China and rise to a position of importance in either government or business. In formulating these careful plans, his elders failed to take into account the young Shao’s similarities with his increasingly eccentric father. A former Governor of Taiwan and later Mayor of Shanghai, Shao Heng was by now enjoying his retirement largely at the expense of the family coffers. By the time Shao met Emily Hahn in 1935 his father’s misbehaviour had become the stuff of family legend; the trail of gambling debts across the city, the countless IOUs in his children’s names and the attempt to pawn the family lands to a debt collector. He is a rake, but his ways are not the ways of the Shanghai rakes I have met, who dance at the Majestic and the Paramount, who play tennis and speak English with each other, and go to Paris once in a while, and take their favourite wives out. Heh-ven’s father is an old-fashioned, die-hard rake, and he wins and loses large sums speculating, and smokes opium, and makes his concubines stay at home.[59]  Fig.6 A fixture of gossip columns since adolescence, Shao's image frequently appeared in the social pages of Shanghai's growing number of lifestyle publicationa [Source: Shanghai Sketch, no.68 (10 August 1929)] Just as his father was the apotheosis of the Shanghai rake, so Shao was, in his youth, the forerunner of the new Shanghai dandy. Dressed in his purple tweed suit, Shao could be seen dashing around town in one of the family’s two automobiles: a brown Nash or a sporty red roadster. Private automobiles, like tweed suits, were still an unheard of luxury, and Shao was understandably a major presence on what was the city’s fledgling social circuit. Known throughout Shanghai’s celebrated pleasure quarters, Shao also entertained lavishly in the best restaurants where he displayed a prodigious knowledge of Chinese and Western cuisine. As was expected of all Shanghai millionaires, Shao maintained a box at the theatre and his every appearance with his then favourite sing-song girl in tow was routinely noted by the voracious mosquito press. It was the young master’s first brush with fame.[60] In 1923, the gossip-hungry Shanghai public became fascinated with Shao’s great passion for the famous actress and renowned beauty, White Lotus (Bailian白蓮). This great affair ended in a suitably melodramatic fashion with Shao’s involvement with the notorious femme fatale, known simply by her English name, Prudence. More scandalous headlines followed with Shao’s arrest for the murder of another of Prudence’s numerous admirers. Though it was later proven to be a case of mistaken identity, Shao’s incarceration lent him a certain cachet and in the years to come he would boast that whilst in jail he had learnt of four ways to commit a murder.[61] Such romantic liaisons continued during his sojourn abroad. In Cambridge, Shao (inspired by Tess of the D’Urbervilles) now found time to develop a sentimental friendship with Lucy, the daughter of a neighbouring farmer. In Paris he embarked upon still more amorous adventures. Dressed in a slouch hat and old clothes, Shao headed straight to the Latin Quarter where he assumed the role of the poor student in pursuit of love. His dashing looks and substantial purse made Shao exceedingly popular with the demi-mondaines, who by his own account dubbed him ‘le beau jeunesse homme’.[62] Years later, Shao would recall these halcyon days in his fictional sketch ‘Josephine’. Here, the ‘poet who eulogised May’ now does the same for the charms of French women, from their golden tresses to their feline temperaments. The informed reader was well aware that this romantic tale of a young peasant from Bourg-la-Reine and her Chinese beau was decidedly autobiographical. While such dalliances far from home might be excused, even admired, any relationship with a foreign woman whilst on Chinese soil was considered, even by the most enlightened intellectual, unthinkable. Still, Shao would flout all moral tenets, be they Eastern or Western, traditional or modern, by his scandalous ‘marriage’ to the American journalist and good-time girl, Emily ‘Mickey’ Hahn. ‘I do love that little bastard, but it’s like playing marbles with quicksilver.’  Fig.7 Emily 'Mickey' Hahn At the time of their ‘marriage’ in 1937, Hahn believed that her frequently rocky three-year relationship with Shao was all but over. Deeply attracted to an Englishman and uncertain about her own prospects in war-torn China, Hahn later admitted that her marriage was as much for convenience as for love. While their union only became common knowledge years later, their relationship was very much in the public eye from day one. No stickler for convention herself, Hahn was a seasoned adventurer and a veteran of numerous romantic entanglements. This young girl from St Louis had rebelled at an early age, becoming the first woman to study the exclusively male discipline of mining engineering at the University of Wisconsin. Later, at the height of the Great Depression, Hahn, by then an aspiring author, began a string of fiery romances that would take her first to Manhattan, then Europe, on to the forests of the Belgian Congo and finally to the exotic Orient. Even after her affair with Shao ended, the scandals continued as Hahn, now in Hong Kong, bore a child out of wedlock to Charles Boxer, then a married man and the local head of the British secret service. It was only to be expected that following her arrival in Shanghai in 1935, Hahn continued to ‘defy every law of decency’ by conducting a very open affair with the much loathed Jewish financier, Sir Victor Sassoon.[65] Yet not even this affaire du coeur could prepare the expatriate community for the shock of Emily’s ‘native passion’. From the very outset this sordid affair, which began shortly after their first meeting in the spring of that year, promised to be an emotional tempest. Not for the first time, Hahn found herself embroiled in a classic love triangle, this time with a notorious womaniser and his patient yet jealous wife, Sheng Peiyu, now heavily pregnant with their sixth child. Shao and Hahn’s ‘marriage’ took place against the backdrop of war and during a personal crisis for Mickey. Knowing that this slip of paper drawn up by Shao would never be recognised under U.S. law, Hahn opted for the security marriage might offer. In a drastic turnaround by the fiercely independent woman, Hahn now contemplated not only moving into the Shao household but also the possibility of having his child. Throughout this tumultuous affair, Shao was more than just a ‘considerate and experienced lover’.[66] Humorous and cultured, Shao was also a business partner who offered Hahn more stimulating work, editing and writing for several of his admittedly short-lived publications, such as Candid Comment and T’ien Hsia Monthly (天下月刊, see also the ‘T’ien Hsia’ section of this issue), an English language journal which featured works by many of China’s intellectual and literary stars. It was also through Shao’s extensive connections that she gained access to the elusive Soong family, and was able to write her best-selling biography of China’s new political dynasty.[67] More importantly, the man who introduced her to the delights of opium also provided her with insight into the mysteries of the ‘real China.’ Hahn’s apartment in Kiangsi Road (江西路, a notorious red-light district) quickly became yet another salon for Shao. In addition to frequent visits from members of her new extended family, Hahn now came into contact, with ‘...poets, artists, teachers and intellectuals…Occasional visitors included the Communist guerrilla leader Mao Tse-tung and his spokesman, Chou En-lai 周恩來…’ not to mention a dapper young gentleman she later learnt to be Chiang Kai-shek’s chief hit man.[68] But real ‘Chinamen’ were not always prepared for Mickey. Zhang Kebiao was so intimidated by her ‘uninhibited behaviour’ that this leading decadent author and essayist decided against continuing their acquaintance. Zhang’s caution was not ill-advised as Hahn was not above satirising the more pretentious of these intellectuals in her columns for The New Yorker. In ‘Cathay and the Muse,’ Hahn wrote of a Mr. Shakespeare who frequently corrected her English pronunciation, along with the various Chinese incarnations of Baudelaire (all confirmed opium smokers), Chesterton, Eliot, Faulkner, and several Henry Jameses.[70]  Fig.8 Shao depicted as Mr Pan, the eccentric central character in Emily Hahn's highly popular stories for the New Yorker Over the years, Hahn wrote extensively about their relationship. Shao appeared as Pan Heh-ven in her comic studies for The New Yorker, as Sun Yuin-long in the fictionalised account of their affair, Steps of the Sun, and under his own name (romanised as Sinmay Zau) in her memoirs of this period, China to Me: A Partial Autobiography. Still, Hahn remained puzzled by the many inconsistencies in Shao’s character. He seemed oblivious to what Hahn regarded as a double standard, and once lambasted a female relative after her arrest for consorting with a foreigner.[71] To Hahn, it was inconceivable that a man who appeared so thoroughly urbane could at times behave like a textbook conservative. Yet, it was these very contradictions which defined the nature and limitations of Shao’s cosmopolitanism. Raised in an environment that offered the best of both Orient and Occident, Shao was the very definition of Shanghai Modern: at home with the world, yet thoroughly Chinese. Shao’s worldliness was, however, quite genuine and not simply an academic appreciation or a mannerism like that assumed by so many of his peers. Throughout his life he remained a staunch opponent of feigned modernity and disdained overseas Chinese for their deplorable habit of speaking English together. And in stark contrast to the new urban dandies who wore their modernity on their sleeves, Shao had long since hung up his dinner suit in favour of more traditional garb. Even in the rarefied atmosphere of the Hong Kong Hotel 香港飯店, Shao stunned the few Chinese present by appearing in a shabby brown scholar’s robe. To all intents and purposes, he was the very portrait of the conservative scholar, one who constantly threatened to grow a pigtail and forget all his English. But unlike his contemporaries lost in the city between two worlds, Shao found himself equally comfortable in both. While this East-West fusion was to make Shao the toast of the city’s ‘integrated’ dinner parties, it was his extravagant behaviour in the salons of Shanghai that would win him both influential friends and powerful enemies within the literary sphere. Vignettes from the Shanghai Beau MondeIf Shao’s life made regular by-lines in the gossip columns of the city’s mosquito press, then it was also perfect material for the style of ‘gossip literature’ that abounded in the 1920s and 1930s. While much of this genre may well have contained more fantasy than fact, writing about Shao required no such leap of imagination. To the casual observer, Shao might have stepped from the pages of a popular Mandarin Duck and Butterfly novella, such as those by the high popular author Zhang Henshui 張恨水 which chronicled the lives and loves of scholars, aristocrats and dilettantes. Instead, his life was handled in a more highbrow, though equally ebullient fashion by one of his most ardent admirers, Zhang Ruogu.  Fig.9 Zhang Ruogu  Fig.10 Cover of Zhang Ruogu's Café Confabulations An active participant in the Francophile salon, Zhang was perhaps best known as the writer of delicate feuilletons which celebrated the romantic urban life of his imagination. Born and raised in the more humble surroundings of the Chinese city, Zhang was naturally impressed by a figure such as Shao. For Zhang, Shao represented more than simply aristocratic good taste. His friendship also provided the author with a connection to the European ideal that Zhang advocated in such works as Exotic Atmospheres, La Vie Littéraire and Café Confabulations. And so it is fitting that Zhang’s sole attempt at fiction also included a thinly veiled portrait of his friend and colleague. Urban Symphonies, as its title suggests, was yet another of Zhang’s paeans to the new metropolis. The title story in this collection begins with an account of the city by night in which Zhang introduces the reader to some of his favourite haunts: the concert hall, the café and the city’s most sumptuous literary salon. The young master’s residence is one of Shanghai’s superior mansions. Built entirely in marble, surrounded by a large garden, and approached by eight pathways wide enough for automobiles, the estate looked like a manifestation of the eight hexagrams with a tall Western building in the middle. The centre of the house formed a hall magnificently decorated like an emperor’s throne room, leading into two smaller yet beautifully appointed rooms; to the east a library and to the west a music room. And there was the host’s private study, where he entertained guests. Here, too, the interior decoration was exceptionally opulent; there was an authentic bust of the poetess Sappho recently excavated in the volcanic city of Pompeii—this item alone was worth 5,000 dollars. Furthermore, there was a manuscript of the English poet Swinburne that had been acquired for 20,000 pounds in London. Their host led them into the music room along the walls of which hung portraits of the great composers. In the centre of the room stood a STEINWAY piano… and right next to it there was a pile of music scores bound in jade-tinted snakeskin.[72] The real life model for this salon was Shao’s new family home on Jiaozhou Road 膠州路. A large brick building set amidst spacious gardens, this residence provided extra room for the ever-expanding family, and facilities to entertain his growing list of acquaintances within the artistic community. While it paled in comparison to Zhang’s hyperbole, the young master’s residence was still a showcase for treasures from the family home and artworks such as paintings by Zhang Daofan 張道藩 (a graduate of both the Slade School of Fine Arts and the École des Beaux Arts who went on to hold senior government and party posts in Nanking and Taiwan) and an oil panting by Ingres picked up during his sojourn in Paris. In this respect, Shao preferred to present a more humble face to the world. His study, as described in his essay ‘Sappho’, is that of the serious intellectual: a cramped room with only enough space for three bookcases, a desk and a few chairs. Soon this Spartan decor would become the result not of modesty but of economic necessity, as Shao sold off the few remaining family heirlooms to make ends meet. By the time Shao met Emily Hahn the family home was little more than a shell. ‘It was bare, as one could see at a glance because the doors stood open between rooms—no carpets, no wallpaper, very little furniture…’[74] In contrast to Zhang’s dreams of golden chambers and chambres separée, the Shanghai salon was quite mundane. Then reality was rarely on Zhang’s agenda. Urban Symphonies, like much of his other work, sought to create a cult of literary celebrity similar to that enjoyed by European writers in the nineteenth century. In Shao, Zhang found his paragon: the Bright Young Thing, the man of letters, and more importantly the living embodiment of Shanghai chic. Shao seemingly had little difficulty in living up to this image. In the late 1920s, while still the darling of the literary scene, he was already making his mark on the city’s salon circuit. Still, it would take more than his dramatic arrival at the wheel of his automobile to impress the serious intellectual. Instead, his puckish wit, irreverence, and ability to amuse would win him friends not only in many sectors of the fragmented literary world but also in society. Ironically, Shao achieved literary celebrity just as the Chinese cultural world reached crisis point. The North-South cultural divide had deepened still further, while in Shanghai itself, the city’s intellectuals were now at each other’s throats as discussed in the opening chapters of this study. Yet Shao would emerge from the ensuing mêlée relatively unscathed. His unlikely survival can, in part, be attributed to his friendships with prominent literary figures from across the political divide. These alliances were forged early in his career as Shao set about conquering the salons of Shanghai. The occasion of Shao’s marriage to his cousin Sheng Peiyu in December 1927 illustrates how quickly Shao became acquainted with the intellectual élite. After a service at the Majestic Hotel, where Shao and his intended wore costumes of the groom’s design, the happy couple returned for a more traditional ceremony at the family home. Only later that month did Shao hold a reception for his friends belonging to the literary and artistic milieux. Though it had been less than a year since his poetic debut, the guest list was nonetheless crammed with such notable figures as Liu Haisu 劉海粟, Huang Jiyuan 黃濟遠, Chang Yu 常玉, Zhang Guangyu 張光宇, Ding Song 丁悚, Zhang Kebiao and Xu Zhimo. The predominance of painters at this gathering suggests that at this early date Shao was far better connected with the city’s bustling art scene than the literary set. Many of these friendships had been forged in Paris a few years earlier when, en route to Cambridge, Shao enrolled at the École des Beaux Arts in Paris. Fortunate to arrive at a time when many of the most talented new Chinese artists were serving their apprenticeship abroad, Shao was quick to become acquainted with those at the heart of the Sino-Parisian art scene. An art-lover, but not a serious artist, Shao was nonetheless a member of the artistic brotherhood known as the Celestial Hound Society (Tiangou hui 天狗會) alongside Xie Shoukang 謝壽康, Xu Beihong 徐悲鴻 and Zhang Daofan.[75]  Fig.11 Shao with fellow members of the Celestial Hound Society at the École des Beaux Arts in Paris, 1925. Pictured from left: Zhang Daofan, Shao Xunmei, Liu Jiwen, Chang Yu and Xie Shoukang. Shao was to prove just as successful in his attempts to befriend the literary giants. With patronage from Xu Zhimo and Zhang Ruogu, Shao quickly became a familiar face at the city’s literary get-togethers. He was now regularly spotted at the weekly gatherings on the second floor of the Xinya Teahouse in North Sichuan Road. This was the city’s most lively and eclectic literary salon where on any given day one could encounter such established authors and poets as Fang Xin 芳信, Zhou Daxiong 周大雄, Fu Yanchang, Li Qingyan 李青岩, Zhao Jingshen 趙景深, Ye Qiuyuan and Yu Dafu.[76] There was also a warm welcome for Shao in the salon of Shanghai’s Francophiles. With his love of the French classics, Shao had much in common with the authors and translators who frequented cafés like the Balkan Milk House and congregated at the home of Zeng Pu in the Rue Massenet. Contact with the city’s Francophiles proved highly productive for Shao, resulting in a series of collaborations with Zhang Ruogu and contributions for the salon’s journal, Zhenmeishan 真美善. Edited by Zeng Pu 曾溥 and his son, Xubai, Zhenmeishan survived despite its limited appeal and from the Zengs, Shao learnt many valuable lessons that he would soon need to survive in the increasingly competitive publishing marketplace. However, Shao’s greatest contribution to the Francophile salon may well have been a prank that played itself out on the pages of Zhenmeishan. The trigger was the publication of Zeng Pu’s translation of Aphrodite (1896), a work of fin de siècle ‘pornography’ by Pierre Louÿs.[77] Haunted by the ghosts of his past, the seriously ill Zeng had lamented to Shao that Chinese women had yet to develop the passionate nature of an Aphrodite. Hoping to revive Zeng’s flagging spirits, Shao wrote to him under the guise of Liu Wuxin 劉舞心, a Catholic schoolgirl who claimed to be an enthusiastic admirer of Aphrodite. Written in a delicate hand on violet paper, this ardent epistle had the desired effect and Zeng published both this and his floral reply in the next issue of the journal. News of Zeng’s new ‘romance’ quickly filtered out into the literary community, and the sales of the next few issues containing their correspondence sky-rocketed. Miss Liu’s familiarity with ‘obscure’ European authors and her ability to quote the works of poets such as Theodore de Banville naturally aroused suspicion in the Francophile circle and at various times Shao, Zhao Jingsheng and Xu Weinan were all suspected of perpetrating a hoax. Shao went to extraordinary lengths to avoid discovery. In order to rekindle the belief in the girl’s existence, Shao enlisted the help of his cousin, asking her to impersonate Miss Liu and hand deliver a letter to the offices of Zhenmeishan. Shortly thereafter, Shao sent Zeng a novel penned by Miss Liu, entitled Consolation (Anwei 安慰) which would ultimately find its way into a special edition of Zhenmeishan dedicated to the works of modern women writers. But as Zeng’s passion for Miss Liu grew stronger, Shao decided to put an end to this deceit. A final letter from Miss Liu stated that owing to ill health she had now moved to Suzhou and did not know when, if ever, she might return to Shanghai.[78] Recalling the Miss Liu hoax years later, Shao remarked that such hijinks were considered a creative exercise in the Shanghai salon of the late 1920s. Yet, this penchant for pranks was soon at odds with the heated stylistic debates and political confrontations that characterised the increasingly acrimonious literary arena. That same year, Shen Congwen made the first attack in his now legendary campaign against the mercenary Shanghai littérateur, sparking a cultural catfight that would rage throughout the coming decade and eventually polarise the literary world. By 1930, there was also a powerful new force in literary circles, one that had little time for Shao’s displays of bourgeois humour. Shao soon discovered he was no longer one of the taste-determining elite, and could only watch as the League of Left-Wing Writers now set the cultural agenda for the new decade. Still, despite his love of serious intellectual debate and regardless of the risk of aesthetic isolation, Shao, the born entertainer, never once missed an opportunity to lighten the tone. ‘Villagers please do not fuck. Here lies Pearl Buck.’ —Shao’s epitaph for the Nobel laureate[79] Shao’s bon mot was as clever as it was vulgar. Referring to the fact that Western cemeteries were commonly used as nocturnal meeting places by Chinese lovers, it illustrated not only the huge cultural divide separating Orient from Occident, but also the differing verdicts on the Nobel Laureate’s literary worth. For the Chinese intellectual, the critical acclaim for Buck’s oeuvre in the West was completely unwarranted and the coarseness of Shao’s remark merely expressed their disdain for the popular author’s brand of Chinoiserie. Though his Western audience was amused by such witticisms, they were just as likely to be his victims. Shao frequently displayed his passion for ‘pulling the foreigner’s leg’ at the soirées of the noted tai-tai 太太 and doyenne of Shanghai society, Bernadine Szold-Fritz. Here, Shao would indulge his hostess’s passion for local culture with impromptu displays of opera, taiji and Peking puppets. Only the few Chinese present were aware that such performances were utter nonsense and derived great pleasure from Szold-Fritz’s obvious delight.[80] But if Shao was one of very few Chinese intellectuals who could move with relative ease between the ‘native’ and ‘expatriate’ communities, he was never the ‘token Chinese.’ No matter what the gathering, Shao always gravitated towards centre stage. Considering his perceived cosmopolitanism, it is not surprising that Shao also became a leading light in the Chinese branch of the international writers association, PEN (Zhongguo bihui 中國筆會).[81] Rather than simply being another forum for ponderous intellectual debate, PEN also offered the opportunity for more social get-togethers. For Shao, this was simply another stage on which to shine and if the recollections of Zhao Jingshen are to be trusted, then at least on one occasion, Shao put in an admirable performance. At one gathering at the Meiyuan 美園, Shao Xunmei was particularly entertaining. He had invited along a number of foreign friends, most notably Emily Hahn. Shao always had the gift of the gab, but on this occasion he was particularly sparkling; a few witty remarks to A one minute, then some words in some foreign tongue to B the next. He and Lin Yutang sang a duet and then Yutang introduced him to a particular foreign lady as an author that every young lady should know.[82] PEN offered a haven for those intellectuals like Shao, Xu Zhimo, Lin Yutang 林语堂, and Zeng Xubai who had resisted the general drift to the left. More importantly, at a time when the city was regularly playing host to a stellar cast of international authors from Rabindranath Tagore and Harold Acton to Somerset Maugham, PEN also came to symbolise a more active engagement with the literary world outside China. Even prior to PEN’s formation, Shao’s celebrity meant that he was one of the nation’s foremost cultural ambassadors on the international stage alongside the likes of Lu Xun and Xu Zhimo. In 1929, Shao and his wife had already garnered a much sought-after invitation to dine privately with Tagore at the home of his close friend, Xu Zhimo. Invitations of this kind became all the more frequent following Shao’s involvement with Emily Hahn, as their growing notoriety made them an obligatory part of the itinerary for visiting cultural dignitaries, like W.H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood, for whom Shao would translate the Chinese verse featured in their 1938 travelogue, Journey to a War.[83] To its critics, however, PEN and similar coteries served as little more than mutual admiration societies. Lu Xun offers a particularly acerbic account of one such function in honour of George Bernard Shaw. Here he describes how the fifty or so authors and starlets privileged enough to receive an invitation crowded around the guest of honour and began ‘bombarding him with questions as if consulting the Encyclopaedia Britannica’. But the situation deteriorated further when Shao (or as Lu Xun referred to him, ‘a man widely regarded as attractive’) presented Shaw with gifts including a novelty ashtray and an opera costume. Shaw’s inquiries as to their origin only elicited eager responses from those present, all designed to highlight the speaker’s ready wit.[84] Significantly, Shao’s status as a literary celebrity proved to be more enduring than his fame as a poet. While he continued to enjoy success in the city’s salons, his poetic career was effectively over. Very soon his fame would come to depend not on his own output but on that of others. It was the beginning of a new chapter in the remarkable story of Shao Xunmei, one which was characterised by both major achievements and great indignities. Publishing and Patronage: the Modern Book CompanyIn Steps of the Sun, Emily Hahn records a conversation between her and Shao’s fictional counterparts which attests to the dramatic shift in Shao’s literary reputation in the 1930s: ‘Are you the Chinese Cocteau, for instance?’ He took these words seriously and considered, ‘Cocteau? No, I will not say that. I am not a poet any more, and even when I was a poet, I was something like Swinburne, but not Cocteau.’ ‘….Well who are you, then?’ ‘The Chinese Northcliffe,’ he said solemnly. ‘ I publish magazines and newspapers. Popular ones. You are disappointed?’[85]  Fig.12 'Salome,' by Mao's close friend and colleague, Ye Qianyu ([Source: Shanghai Sketch, no. 36 (12 February 1928)] Sadly, there were few to lament the passing of the Chinese Verlaine. If Paradise and May can be said to have captured the mid-twenties Zeitgeist, then by the time Shao’s final collection of verse, Twenty-five Poems (Shi ershiwu shou 詩二十五首), appeared in 1936, his particular brand of aestheticism was looking decidedly stale. Much had changed in the literary world since the appearance of Flower-like Evil eight years earlier. In an era of rampant nationalism and political turmoil, the literary arena was now polarised. It was a marketplace where works by the strident Left competed for sales with the urban romances of the Neo-Sensualist School (Xin ganjue pai 新感覺派). What little attention Twenty-five Poems did garner was again predominately negative. To his contemporaries, Shao’s depiction of beauty as an ethereal female spirit, his use of religious (specifically Catholic) imagery, and the decadent union of beauty and evil was out of keeping with the new proletarian age. Ironically, contemporary scholars are almost unanimous in calling this final collection of verse Shao’s most sophisticated work; a judgement that was shared by Shao’s few remaining supporters in the literary world. Chen Mengjia 陳夢家, who as the son of a Protestant clergyman could well understand the ‘blasphemous’ nature of Shao’s work, remarked that the gentle beauty found in ‘Xunmei’s dream’ was akin to ‘a piece of jade heaping praise upon another piece of jade’.[86] The author seemed equally proud of this collection. In his lengthy prelude to Twenty-five Poems, Shao was quick to distinguish these more mature works from those that preceded them, dismissing all his previous work as that of a ‘youthful braggadocio’. For Shao, this earlier verse, which helped secure his place among the literary elite, now seemed ‘pitifully naïve’ and ‘an exquisitely ornate creation, which while pleasing to the ear and the eye had meaning only at a superficial level’.[87] Still more revealing was his admission that his earliest efforts were not influenced by Japanese haiku as some suspected but were simply ‘abridged or altered versions of famous English poems’.[88] While this apologia may well have suggested a new beginning, in actuality it signalled the rather ignominious conclusion to what had once seemed a promising literary career. So alluring is the mythology surrounding Shao, that his privileged upbringing, aristocratic persona and even the timbre of his verse all suggest that he lived in a sumptuous fantasy world. By 1936, this was certainly not the case. The financial reality facing Shao as head of the family meant that a career in poetry, a dream he had harboured since youth, was now an unaffordable luxury. Even before the publication of Twenty-five Poems, Shao was directing his energy towards publishing in a desperate attempt to make ends meet. Shao’s vision for his new career was in many senses as grandiose as his poetry and one that would eventually spell the end of the family fortune. Though they had managed to keep up appearances, for some years the Shao clan had suffered from cash flow problems. As early as 1928, the spendthrift ways of Shao’s father and many of his offspring had forced the family to take desperate measures. The solution to their monetary woes was an ambitious construction project which would see a large longtang 弄堂 apartment complex built on the family land stretching from Bubbling Well Road in the north to Burkill Road 白克路 in the south.[89] Having borrowed a substantial sum of money to complete this mammoth undertaking, the family soon discovered that the rents received from these properties were barely sufficient to cover their spiralling living costs. By February 1932, when Shao’s aunt (and adoptive mother) passed away, the family, still lumbered with hefty mortgage repayments, struggled to scrape together sufficient funds to pay for a funeral worthy of the family’s matriarch. Less than two years later and in danger of defaulting on their loans, Shao sold the family’s remaining property holdings in Shanghai to the bank. Left with only the ancestral lands and a little capital, Shao now became the family’s sole bread-winner. This plan to reinvent himself as a publishing magnate was not entirely untenable. While not known for his business acumen, Shao’s previous publishing ventures had at least taught him some of the many pitfalls he would need to avoid in future. Furthermore, his extensive connections would ensure there was never a shortage of high profile contributors for the many publications he had on the drawing board. Perhaps most important to Shao was that his new career as gentleman-publisher secured (no matter how tenuously) his place in the limelight. With the family’s remaining capital, Shao now purchased what would be the backbone of his publishing empire. Complete with rotogravure section, Shao’s new printing press was in its day the most sophisticated piece of equipment of its kind ever imported into China. Shao’s rationale for so extravagant a purchase was that the income this equipment was sure to generate from printing the works of his competitors would in turn subsidize his own publications. These he envisaged as the equal of Western glossy magazines such as Life and Harper’s Bazaar which were certain to appeal to the fashion-conscious reading public of Shanghai. With Paris-trained Gao Yuanzai 高元宰 installed as head technician, Shao’s golden age of publishing could now begin. Up until this point, Shao’s track record in the publishing industry had been anything but glorious. While still busy with his vanity publication The Golden Chamber, Shao was simultaneously involved with the Crescent Moon Monthly (Xinyue yuekan 新月月刊), which had been founded in March 1928. To Shao this was a highly attractive undertaking for not only did it provide the opportunity to work alongside his close friend, Xu Zhimo, but also involvement with a prestigious and successful publication which counted Hu Shi, Liang Shiqiu, Lin Yutang and Shen Congwen as regular contributors. However, all did not go to plan. Despite his financial investment and position on the editorial team, Shao found he had little say in the day-to-day running of the publication. With Xu’s untimely death in November 1931, Shao not only lost his closest ally but now found himself increasingly isolated from his colleagues. Faced with widely differing agenda, the migration to Beiping by many of the movement’s leading lights, and staunch opposition to change by the likes of Luo Longji 羅隆基, Shao finally canvassed sufficient support to close the magazine in June 1933. Clearly, Shao did not come away from the Crescent Moon debacle empty-handed. With first-hand experience of the destruction inflicted by the clash of giant egos, he was clear that in regards to future publishing ventures it would be best to go it alone. More importantly, he developed a friendship with Lin Yutang; a partnership that would spawn one of Shao’s most successful publishing concerns. Rebounding from this somewhat disastrous foray into the world of serious publishing, Shao soon launched a still more ambitious undertaking; the Epoch Book Company (Shidai tushu gongsi 時代圖書公司). In 1934, the former Crescent Moon offices in Jiujiang Road 九江路 became home to what Shao hoped would soon become a new publishing empire. From here he unveiled his blueprint for an astonishing variety of new publications, from illustrated journals to bilingual periodicals, many of which he would ultimately realise with varying degrees of success. A notable omission from this catalogue was the type of highbrow journals in which he had formerly specialised. Rather than catering to a limited number of friends and colleagues, Shao’s was now aiming at the city’s increasingly sophisticated petty-bourgeoisie hungry for entertainment and enlightenment. Publications such as The Young Companion had proven that a huge market existed for this particular brand of lifestyle publication and Shao was keen to capitalise on their success. In severe financial distress, Shao had but one option left open to him; kowtow to the vulgar. Appearing almost two years prior to the formation of Shao’s new publishing empire, Modern Miscellany (Shidai huabao 時代畫報 also known in English as Epoch Pictorial) was the prototype for all the publications in Shao’s stable.[90] The brainchild of Zhang Guangyu, Zhang Zhenyu and Ye Qianyu, Modern Miscellany had originally been designed as a successor to their earlier venture Shanghai Sketch (Shanghai manhua上海漫畫) which had ceased publication in June 1930. It was Zhang Zhenyu who formally approached Shao and the artist Cao Hanmei with a proposal to form a new publishing venture. With Shao and Cao both investing the not insubstantial sum of two thousand yuan, the Modern Book Company was born. Modelled on its predecessor, Shanghai Sketch, Modern Miscellany featured the same mixture of photographs, cartoons, social news and more lightweight editorial content and its limited success encouraged Shao to employ the same formula in subsequent ventures. However, new publications such as Epoch Literature (Shidai wenxue 時代文學) and Epoch Cinema (Shidai dianying 時代電影) were competing in a marketplace close to saturation point and Shao soon learnt that not even their high quality format or famous feature writers could guarantee sales.[91] Whereas Shao’s poetic career might be characterised as dramatic yet static, his publishing career was one of ceaseless change and constant innovation. Though catering for less refined tastes, Shao was still able to assemble the best new talent the city had to offer in order to staff the growing list of publications under the Epoch banner. In doing so, he added yet another feather to his cap, the role of patron. The launching pad for a new generation of artists, poets, translators and authors, Epoch was perhaps the single greatest achievement of Shao’s literary career. Though he benefited immensely from their involvement, Shao cannot be cast as the cynical businessman exploiting a pool of cheap labour and his continued largesse suggests he was only too happy to use his literary celebrity to advance their careers. With political confrontation and mud-slinging now the favoured pastimes of the literary giants, Shao found refuge in the company of a younger and less bitter circle. Wang Yingxia 王英霞, Zhu Weiji and Li Qingyan were just some of the now well-respected figures to bring their works to Shao for his perusal. But Shao’s influence was still more discernible in his sponsorship of three young poets: Chen Mengjia, He Jiahuai 何家槐 and Xu Chi 徐遲, all of whom were then students at Guanghua University (Guanghua daxue 光華大學). Though no longer fashionable as a poet himself, Shao shared with this younger generation a Western aesthetic sensibility and a preoccupation with the beauty of poetic form, in particular the close attention paid to structure, diction and rhyme. This was also the period that Shao composed some of his most important though frequently over-looked pieces of literary criticism, including, ‘Poetry Chronicle’ (Xinshi licheng 新詩里程) and ‘A One-way Conversation’ (Yige rende tanhua 一個人的談話) which so impressed Shen Congwen that he felt move to write, ‘I have never read such a well written essay.’[92] Epoch publications also displayed Shao’s continued fixation with the visual appeal of his books and journals. To this end, he once again began consorting with the city’s leading artists and it was their input that was largely responsible for the polish these publications might otherwise have lacked. Shao did not merely co-opt established artists such the aforementioned Zhang brothers and Ye Qianyu whose classic cartoon series ‘Mr Wang’ 王先生 appeared in Modern Miscellany, he also encouraged contributions from many up-and coming talents including Lu Zhixiang 陸志庠 and Ding Cong 丁聰 to name but a few. Aware of the growing public appetite for this new art form, he quickly put two new magazines into production: Cartoon World (Manhua jie 漫畫界) and Epoch Cartoons, edited by Lu Shaofei and Wang Dunqing. Sadly these promising publications ultimately ran afoul of the authorities and were closed down in 1936 and 1937 respectively.[93]  Fig.13 Ye Qianyu's famous cartoon strip, 'Mr Wang,' which ran in Shao's flagship journal Modern Miscellany