|

FEATURES

The Transition from Palace to Museum | China Heritage Quarterly

Reproduction of the cover of the earliest published guidebook of the Guwu Chenliesuo (Government Museum).

The Transition from Palace to Museum:

The Palace Museum's Prehistory and Republican Years

The Palace Museum opened the doors of the Forbidden City's rear palaces to the public for the first time in 1925, after those buildings and their antecedents had served for approximately six centuries as the secluded demesne of Ming and Qing emperors. Yet, its opening only took place because the emperor had been finally forced to honour an agreement of favourable treatment brokered by Yuan Shikai (Fig. 1) in 1912, which guaranteed that the royal family would be free to move to the Summer Palace (Yihe Yuan) in the north-west of Beijing. From the time of its founding, the Palace Museum would go on to survive civil wars, World War II (1937-45) and the 'Cultural Revolution' years (c.1964-78), yet little is known today about the decade of intrigue that culminated in the establishment of the museum.

Fig. 1 Photograph of Yuan Shikai in full military regalia in 1912

The Gallery of Antiquities

The origins of the Palace Museum actually go back to 1914, when the museum's prototypical ancestor was founded. It was known as the Guwu Chenliesuo, literally meaning, 'Gallery of Antiquities' and often simply termed in English the Government Museum. The Government Museum was established in the southern outer court of the Forbidden City, even closer than the Palace Museum of 1925 to the rival seats of power in post-revolutionary Beijing. The southern outer court contained the 'Three Front Halls'—Taihe Dian, Zhonghe Dian and Baohe Dian—the first vital in the ascension of new emperors to the throne.

The Government Museum was thus geographically positioned between the forces of restoration, represented by the emperor still ensconced in the Forbidden City, and the Beiyang warlords, represented by Yuan Shikai, with his headquarters in the Zhongnan Hai or "Sea Palaces" on the western side of the Forbidden City. Yuan simultaneously fulfilled the roles of warlord, self-negotiated President of the Republic, and ultimately pretender to the restoration throne. Politically, the Nationalist revolution, represented for the time being also by Yuan Shikai, was exerting pressure on him from Nanjing. In some senses, these forces all laid claim to the imperial collections.

The peculiar history of the museums established in the Republican period within the grounds of the Imperial Palace hinged on the ambiguity regarding the ownership of the imperial collections in the wake of the 1911 Revolution, and what these collections signified politically. This is not to deny that there was an interest at that time among some reformers and scholars in establishing a public museum in China. In the late 19th century a number of reformist scholars had travelled to Europe, North America and other parts of the world, where they had observed at first hand examples of museums as the centrepiece and embodiment of civic and instructional virtues.

Many 19th century museums were a conflation of the interest in curiosities and peculiarities, not to mention beautiful and valuable objects, with the perceived need of the administrators for an edifice celebrating and glorifying the state, and often its imperial reach. Many museums signified royal largesse to blessed subjects. Some 19th century Chinese travel accounts and magazine articles pointedly praised the museums of the world, and the museum as an institution appealed to Chinese literati with their long traditions of collecting and treasuring antiquities and curios, as well as their veneration for education. In 1905, the reformer and entrepreneur Zhang Jian (1853-1926) initiated a memorial to the throne urging the emperor to emulate Japan's Meiji Emperor and establish a museum or dishi bolanguan ('royal household museum' or 'exposition'), as Zhang styled it, to display objects from the royal collection. He later suggested that prototypical institutions of a similar nature be set up, one in each province, so that these educational halls could be promoted nationwide. To this end, he was also the first Chinese entrepreneur to establish, in Nantong in 1905, a 'modern' museum conceived as a central urban institution open to the public. His appeal to the throne, however, went unheeded. Zhang Jian reiterated his proposal in 1913, but now he addressed the new republican government.

Another early proponent of a state-established museum was Jin Liang, director of the Royal Lodge in Shengjing (today's Shenyang), which was under the auspices of the Imperial Household Office. In 1910, Jin proposed that a gallery be set aside to display to the public items from the royal lodge's collection. After the abdication of the Qing monarch, he remained in the service of the defunct Xuantong Emperor, Puyi, and proposed on three occasions that his master display his collections.

Chinese politics remained highly fluid during the years following the 1911 Revolution: warlords were in the ascendancy in Beijing; the victory of the revolution was far from decisive, and the presence of the abdicated emperor lent weight to the possibility that the monarchy could readily be restored.

Many of the politicians and other individuals who facilitated the establishment in 1914 of the Government Museum (Guwu Chenliesuo, renamed the Neiwubu Guwu Chenliesuo in 1916) were motivated primarily by the need to occupy the palace space, specifically the ceremonial halls of the outer court and thereby thwart any restoration of the monarchy. The ownership of the items of the palace collections also required clarification, as these had the cachet of state legitimisation in the absence of republican credentials of authority.

Fig. 2 Portrait of Princess Wanrong, consort of Puyi

The founders of both the Government Museum and the Palace Museum found themselves caught between the forces of the restoration, the warlords and the republican revolution, and so the establishment of these two institutions was conducted covertly. Tentative moves towards creating a national museum in the Forbidden City were initiated almost immediately following the Dowager Empress Longyu's announcement to Yuan Shikai on 1 February 1912 of the decision that she and the emperor would abdicate. The abdication agreement, called 'The Articles for the Favourable Treatment of the Great Qing Emperor', represented a bloodless revolution in Beijing, but created ambiguity regarding the ownership and custody of the vast imperial collections of antiquities. The agreement also enabled Yuan Shikai to install himself as president; in return, the Republican government offered to treat the Qing emperor courteously, extending to him a four-million-tael annuity while taking control of the imperial court's budget. It also granted the emperor, his empress Wanrong (Fig. 2) and his family the right to reside at the Yihe Yuan (Summer Palace) with six hundred eunuchs, numerous attendants and guards, under the supervision of the empress dowagers. It also permitted him to remain temporarily in the rear quarters of the Forbidden City until accommodation at the Yihe Yuan could be prepared. The seventh article of the agreement stated that the emperor's private property would be protected by the Republican government. However, the ownership of these art treasures and other artefacts was not clarified. Shortly after the abdication, Yuan Shikai initiated the construction of a presidential palace for himself in Zhongnan Hai, the adjoining section of the imperial city west of the Forbidden City.

The royal collections were widely scattered, far beyond the confines of the Forbidden City; the royal mausoleums, the royal lodges, the summer palaces and hunting grounds, and the ancestral places all housed valuable items. Moreover, pillage and theft thwarted the efforts of the most scrupulous custodians of these collections in the last century of the Qing dynasty as corruption spread and collapse advanced. However, breaches in security accelerated dramatically following the plunder of the Forbidden City and the razing of Yuanming Yuan by the Anglo-French expedition in 1860 and the occupation of the Forbidden City by the Allied Expeditionary Forces in 1900-1901. After the 1911 Revolution, it soon became clear that there was an urgent need to establish institutions and mechanisms for preventing the collections of the Forbidden City and other royal establishments being sold off by the abdicated royal family and its retainers, who regarded them as their personal property.

A Consolidated Imperial Patrimony

After July 1913, when the military governor of Jehol (Rehe) in Hebei province, Xiong Xiling, became prime minister and treasurer of the new Republican government, precious items from the royal collections at the imperial summer retreat at Chengde began appearing on the antique markets of Beijing, Tianjin and Shanghai, as well as in Chengde itself. Yuan Shikai had Xiong despatch an investigative team, led by Xu Shiying, to Chengde. However, as the investigation unfolded, associates of Xiong himself were implicated. Xiong Xiling wrote to Yuan Shikai asking him to spare the accused, while he himself resigned his position, although he remained in the government. From antique dealers in Beijing and other cities, the government seized 229 objects that had come from the imperial summer retreat. There was a general plea to move the remaining items from the imperial collections in Chengde and Shengjing (Shenyang) to the Forbidden City in Beijing for safekeeping.

At the time of this pilfering scandal, an official of the Department of Internal Affairs, Jin Cheng, proposed to the department's zongzhang (general secretary), Zhu Qiqian, that China should emulate France's management of the Louvre and move the imperial collections from the Chengde imperial summer resort and the palace in Shenyang to Beijing for safekeeping in part of the Forbidden City under the administration of the Department of Internal Affairs. Jin Cheng also proposed that a 'museum' be established so that these items could be exhibited to the public. He offered to draft the regulations governing the new body. For this, he had some experience, having studied law in the United Kingdom during the closing years of the Qing dynasty. He had also travelled at that time to about a dozen countries, where, as a result of his interest in art, he visited art galleries and museums. Following the establishment of the Republic he had taken a position in the Department of Internal Affairs, although later he would go on to become a prominent artist.

Jin Cheng's proposal was welcomed by the authorities because it enabled the halls in the southern outer court of the Forbidden City to be converted into a museum, thus removing them from the keen eye of potential restoration activists. Moreover, it was also an ideal location for safely housing the collections from Chengde and Shenyang. This would also be a practical measure that would conform to the October 1912 proposal of the Department of Internal Affairs to establish a place to preserve Chinese cultural relics and prevent them from going abroad. Zhu Qiqian was delighted by this suggestion and was able to secure $US200,000 of Boxer Indemnity money returned by the USA to set up the museum. He was adamant that these displays be prepared promptly because the proposal in July 1912 for the establishment of a national museum issued by Cai Yuanpei, the Minister of Education, had been delayed, and would not be acted upon until 1926 for financial reasons.

The Department of Internal Affairs of the Republican government acted swiftly to move to Beijing the royal collections from Chengde, Shenyang and the Summer Palace in Beijing. It was originally intended that, apart from a small quantity which would remain the property of the royal household, the remainder would become state property and be moved to Beijing for storage and exhibition. Treasures from the summer retreat at Chengde were transported to Beijing in seven consignments over a twelve-month period from November 1913 onwards. The consignments totalled more than 119,500 objects, or sets of objects, including furniture, interior decorative items, bronzes, jade objects, works of calligraphy and painting, clocks, books, carpets and sundry items (including 43 live deer!). Over two months, from January 1914 onwards, some 114,600 precious objects were shipped in six consignments from Shenyang to Beijing.

Fig. 3 Plaque of the newly restored Wuying Dian, the original venue of the Government Museum

Events moved quickly. On 24 December 1913, the Department of Internal Affairs drafted the articles for the establishment of the new museum and, by 30 December, the newly established Government Museum had requisitioned two rooms of Wuying Dian, or Hall of Military Prowess (Fig. 3), to take receipt of them. However, it was only in 1914 that an agreement was reached stating that, although the treasures in Beijing were the private property of the imperial family, the articles moved to Beijing from the outer collections were to be purchased by the Republican government, for a sum to be decided by an independent assessor. The Republican government did not, however, have the purchase price, and so the items were technically on loan until paid for. On 4 February of the following year, the constitution of the Government Museum was made public. The swift actions of Yuan Shikai, ostensibly representing the Republican government, between the time of the original decision to establish the Government Museum until March 1914, when the masses of crated cultural relics from north-eastern China were piled up in Beijing, was possibly motivated by Yuan's desire to occupy Wuying Dian, the 'coronation hall' of the Forbidden City.

The Hall of Military Prowess: Wuying Dian

The Department of Internal Affairs entrusted the work of converting Wuying Dian into an exhibition space and joining it to Jingsi Dian (Hall of Tranquil Contemplation) at its rear to the German architectural firm of Curt Rothwegel, based in Qingdao. The company had a reputation for working with stone; in 1908 Rothwegel had begun construction of the Evangelical Church of Qingdao, and in 1915 refurbished Qianmen gate in Beijing, opening up four archways through the gate facilitating entry and exit. In demolishing the enceintes that surrounded Qianmen, Rothwegel became the first architect or engineer to remove walled structures in China to facilitate motor transport.

The negotiation of the contract with Curt Rothwegel's firm and the practical supervision of the project were entrusted to Jin Cheng. He oversaw the collection of valuable nanmu and other timbers from collapsed buildings in the vicinity of Xian'an Gong and Nanxun Dian. In May 1914, Wuying Dian was equipped with the first telephone line to be connected to the Forbidden City and, in July, following a panic when a fire broke out at Xihua Men, the western entrance to the Forbidden City, water mains were laid to the new museum.

Fig. 4 View of Baoyun Lou, the Treasure Collections Building, constructed by the firm of Curt Rothwegel.

On 10 October 1914, the displays of bronzes, jades and porcelain from imperial kilns in Wuying Dian, China's first state-run museum, were opened to the public without fanfare, even though the museum buildings were not yet completed. The displays were crammed, and very few were labelled. The later famous writer Lu Xun visited on 24 October, and commented in his diary that the museum was like an 'antique shop'. Despite the overthrow of the monarchy with the 1911 Revolution, the Government Museum retained the aura of a 'royal museum' as long as Emperor Puyi remained in residence in the Imperial Palace. Out of caution and deference, the opening was low-key and given little publicity. The government only issued tickets directly to other government organisations. In 1914, only Wuying Dian was open to the public, but later Wenhua Dian (Hall of Civilising Transformation) and the section of the display at the rear in Zhujiang Dian became part of the Government Museum. Two construction companies were also hired to build a Western-style building, Baoyun Lou (Fig. 4), that would provide storage space for the museum.

Although crammed with the evidence of royal accumulation, the Government Museum conveyed little idea of how royal life was lived in the rear palaces of the Forbidden City, with one small concession. Wuying Dian preserved the Yude Tang (Hall of Bathing Virtue), the well, boiler and pipes of the Turkish style bathing facility, which the Qianlong Emperor had supposedly fitted out for his young consort from Xinjiang, Xiang Fei ('Fragrant Concubine'). Displayed here were items of the martial and daily attire of this imperial favourite, as well as a marble Buddha and a cloisonné brazier.

Entry tickets were initially expensive, in order to limit the number of persons visiting the exhibitions. Duan Yong estimates that a 'comprehensive' ticket, which afforded members of the public entry to all the halls of the outer court (Wuying and Wenhua, as well as the Three Outer Halls—Taihe, Zhonghe and Baohe) would have cost the equivalent of one third of a Beijing commoner's monthly salary. In the first two years of operation, the policy succeeded in limiting visitors and excluding the general public; most visitors were prominent officials and citizens, or members of Beijing's large foreign community. However, in 1916, half-price tickets were introduced for academic groups and for the general public at festive times. Military personnel were also sold discount tickets, while students, mostly from Tsinghua University College, were admitted for free.

At this time Wenhua Dian was also opened and its displays featured items of calligraphy, painting and embroidery. After the failure of Yuan Shikai's attempt in 1915 to restore the monarchy, the Republican government's more concerted efforts to open the Government Museum and adjacent areas of the palace to the public resulted in the museum receiving 16,000 visitors in 1916. The staff of the Government Museum also began to address broader museological and curatorial functions, such as the preservation and conservation of antiquities, the preservation and restoration of the buildings of the Forbidden City, as well as issues related to academic research and publication.

Greater attention was also paid to security. Moves were made to end or thwart the practice of high-level officials treating the collection as a repository of gifts for eminent persons; in this, Republican officials were simply emulating the practice of the imperial family who still remained in the northern, rear area of the Forbidden City, having not yet moved to the Summer Palace. Puyi and other denizens of the imperial apartments regularly pilfered items from the collection, either by asserting that they were sending out objects to be repaired or presenting them to retainers as rewards for services rendered.

On 31 May 1916, museum staff discovered that one of the display cases in the Government Museum had been forced open and a number of valuable items were missing, including large bronzes, a gilded plate, a white jade paired-dragon cup and a platter with a gold handle. Three guards were suspected of being the thieves and they were handed over to the police. For more than a decade thereafter, there were no further robberies at the Government Museum, in stark contrast to the situation prevailing in the imperial apartments. While the Government Museum was initially entrusted only with the task of 'preserving antiquities' (baochi guwu), thus being a prototypical, rather than a fully-fledged museum, this situation had gradually changed.

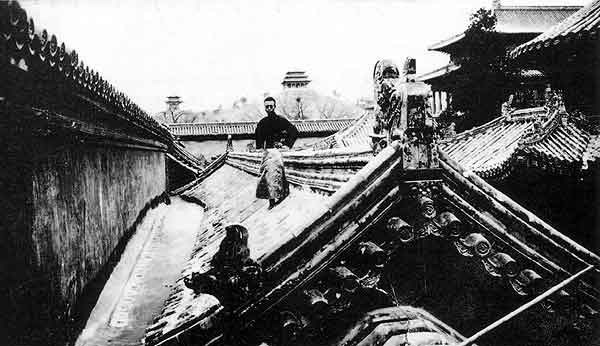

Fig. 5 Photograph showing Puyi on the roof of the imperial apartments, Forbidden City, with Prospect Hill, or Jing Shan, visible in the background.

Plunder of the royal collections in the rear courts of the palace went on unabated. Emperor Puyi (Fig. 5), his brother Pujie and other relatives, as well as the eunuchs and lesser attendants, were all adroit at removing items from the palace collection. Emperor's Puyi's Scottish tutor, Reginald Johnston, and Puyi himself have documented how valuable treasures were purloined. In 1923, Puyi announced that an inventory of items of the Qianlong Emperor's collection in the Qianfu Gong (Hall) would be drawn up, but this panicked the eunuchs. The Qianfu Gong was burned to the ground in less than mysterious circumstances, and, according to Chang Lin-sheng, only 387 items were salvaged of the originally inventoried 6,643 items. Perhaps to remove the evidence of this 'fire sale', the emperor had a tennis court built on the site of the razed building. Puyi saw the writing on the wall, and spent most of his time in the residence of his father, the Northern Mansion (Bei Fu) outside the Forbidden City. He ordered that 1,000 of the eunuchs and attendants be expelled. Not surprisingly, after leaving the palace, many of the eunuchs opened antique shops in the Qianmen district. Langfang county in Hebei, where many of the eunuchs came from, also became a 'wholesale centre' for antique dealers. Unfortunately, Puyi and his brother Pujie knew how the inventory system worked and when they visited the Forbidden City each day to attend lessons they would remove some of the most valuable items (those indicated in the inventory with five circles) to an outside hiding place. It is estimated that they removed between one and two thousand highly valuable scroll paintings, albums and works of calligraphy. These were packed into more than seventy or eighty crates and shipped for safekeeping to Tianjin, in preparation for possible escape.

In 1924, Puyi and the imperial family began to make the final preparations to move to the Summer Palace, finally fulfilling the agreement that was part of the 1912 Articles of Favourable Treatment. The move again raised the question of ownership of the items in the palace collection, although there was little public sympathy left for Puyi or the court. The move to the Summer Palace did not take place, however, and an unexpected coup saw Puyi and his household expelled from the palace by the warlord Feng Yuxiang on 5 November 1924. The Articles of Favourable Treatment were revised and the emperor was now only left with clothing, personal items and some 'heirloom' antiques. Thereafter Puyi moved to the Japanese Concession in Tianjin, where he had laid in his supply of antiquities, later taking up a Japanese invitation to go to Manchuria. His fate was, in a sense, sealed, as was that of many of the palace treasures he took with him.

Committee for Liquidation of the Qing Household

On 6 November 1924, the day after the imperial family was expelled from the Forbidden City, in order to prevent further theft, the government appointed Li Yuying, a leading art historian as chairman of the Committee for Liquidation of the Qing Household. In December 1924, Li's team of specialists moved into the Forbidden City and began preparing a catalogue of the royal collection. Since many of them, including Shen Jianshi, Shen Yinmo and Ma Heng, were professors from Peking University, their students had the opportunity to become their assistants. Among the students were Shan Shiyuan and Na Zhiliang. These two men were the last remaining members of the original team in the 1990s, and both have left valuable accounts of their work at this time in the Forbidden City, the soon-to-be established Palace Museum. Ironically, Shan would remain working in Beijing/Beiping, while Na Zhiliang would go on to become a senior curator at the National Palace Museum in Taipei. In a recently published account (see the appended Bibliography), Shan Shiyuan describes the appalling condition of the Forbidden City when it was vacated by Puyi and his entourage. Many of the rooms were piled with rubbish, and the cataloguers had to be careful when handling this rubble because it sometimes contained valuable items. To prevent the scholars themselves purloining artefacts, they were required to wear dust jackets with no pockets and sleeves bound tightly by white bands, a style of clothing still familiar in many mainland institutions. After nine months of efficient work, the committee published a 28-volume inventory of the collection, which then numbered more than 1.17 million pieces.

The rear palaces of the Forbidden City were opened to the public for the first time on 10 October 1925, and named the 'Gugong Gongli Bowuyuan' (Palace Museum). The museum was a 'public' (gongli), rather than a 'state' or 'national' (guoli), institution, and was therefore less generously funded than the Government Museum. The Republican government was also concerned to bring down entry fees to the palace itself, as a way of consolidating popular support, whereas the Government Museum aimed to attract a more elite audience. The curators of the new Palace Museum were intent on preserving the palace buildings as they had been lived in by the royal family, perhaps as an object lesson in decadence, and to display to the public all the documents related to the restoration attempt in 1915, and to a later attempt, by Zhang Xun, in 1917.

Fig. 6 Photograph of Ma Heng

The renowned scholar Yi Peiji was appointed the first curator of the Palace Museum. He provided the museum with effective management until 1931, when he was forced to quit his post, having been accused by a political rival of stealing art from the museum. He died soon thereafter. The scholar and archaeologist Ma Heng (1881-1955) (Fig. 6) became director of the Palace Museum in 1933, and would remain in charge until he retired in 1954.

This competition from the Palace Museum spurred the curators of the Government Museum to devote more effort to cataloguing the entire collection. They prepared plans and maps of the entire museum area, and allowed scholars from outside and abroad to avail themselves of new research facilities comprising three rooms in the western wing of Wuying Dian. (Fig. 7) The directors also established the Association of Chinese Academic Organisations (Zhongguo Xueshu Tuanti Xiehui) and set up a Committee for the Appraisal and Authentication of Antiquities (Guwu Jianding Weiyuanhui), which included both Chinese and foreign scholars. They invited painters to establish the Chinese Traditional Painting Research Institute (Guohua Yanjiushi) located on their premises. These moves marked the fully-fledged beginnings of the museum's academic and intellectual role.

Fig. 7 The newly restored Wuying Dian, the original home of the Government Museum.

In 1926, the government even proposed that the Government Museum be integrated with the Palace Museum to form a guoli bowuyuan (national museum); ironically, this proposal did not come to fruition and the institution bearing that title is now located in Taipei. Yet, the Government Museum was not integrated with the Palace Museum until 1948, twenty-three years after the latter institution was founded.

Evacuating to the South

In 1928, the Nanjing government was finally successful in overthrowing the warlord government in Beijing in what has become known to history as the Northern Expedition. This marks a watershed in the development of the Palace Museum. Now, three years after its establishment, the Palace Museum was placed under the direct control of the Republican government and, in 1933, under the administration of the Executive Yuan. Thereafter, the Government Museum fell into decline, because its directors—Yang Naigeng, Wu Hanzhang and Zhou Zhaoxiang, had all been high-level officials of the Beiyang warlord government. Support for the Government Museum from the Nanjing government gradually waned. The Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek's supporters took over the management of the Palace Museum, while the Government Museum came under the administration of the Beiping Dang'an Baoguanchu (Beiping Archives Preservation and Management Office) of the Department of Home Affairs of the Nanjing government.

For a brief time in 1930, when fighting broke out in the Beiping-Tianjin area between the warlord armies of Yan Xishan and Feng Yuxiang, the Government Museum was freed from the administration of the Nanjing government, and the plaques stating that affiliation were removed from outside its buildings. In 1930, ten directors (lishi) on the board of the Palace Museum, chaired by Chiang Kai-shek, issued a document titled 'Method of Realizing the Preservation of the Gugong' (Wanzheng Gugong baoguan banfa), a document that signalled an intention to bring the Government Museum under the control of the Palace Museum. This proposal was, however, temporarily shelved because of the September 18 Incident—the Japanese invasion of Manchuria—and plans for shared ticketing for both museums were also dropped.

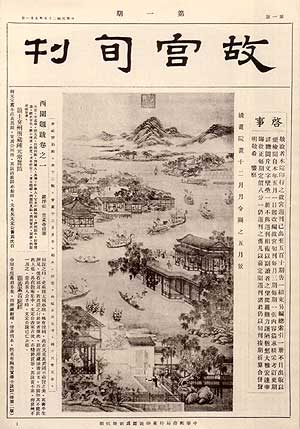

Fig. 8 Front cover of an issue from 1936 of the popular museum journal Gugong Xunkan (originally titled, Gugong Zhoukan)

At that time, a number of scholars were recruited to work in the Palace Museum. A board of thirty prominent individuals drawn from political, military, cultural, religious and educational circles oversaw its administration, and the government issued a set of rules of incorporation. The museum was also promoted to the general public through publications and the press. (Fig. 8) In 1935, the China Museums Association was established in Beiping and the director of the Palace Museum, Ma Heng, was chosen to be the first head of the new association.

In 1931, following the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, the central government ordered staff at the Palace Museum and the Government Museum to select the most important pieces in the royal collection and prepare to send them secretly to Nanjing, then the national capital. The Government Museum directors were opposed to the proposal, knowing that it would remove them from their 'power base' in Beiping and believed that it would signal an unwillingness to defend the former capital; director Zhou Zhaoxiang signalled his opposition to the government's decision in a speech to staff members and government officials delivered in Taihe Hall. The Nanjing government responded by bringing its agenda forward, and the Executive Yuan and Department of Home Affairs despatched specialists to Beiping to oversee the move. Zhou was detained to signal the Nanjing government's determination to abide by its decision, while the work of crating the exhibits proceeded. The Government Museum prepared 111,549 objects for the move south. This not only included antiquities from the collection, but also large items of furniture, and, significantly, thrones.

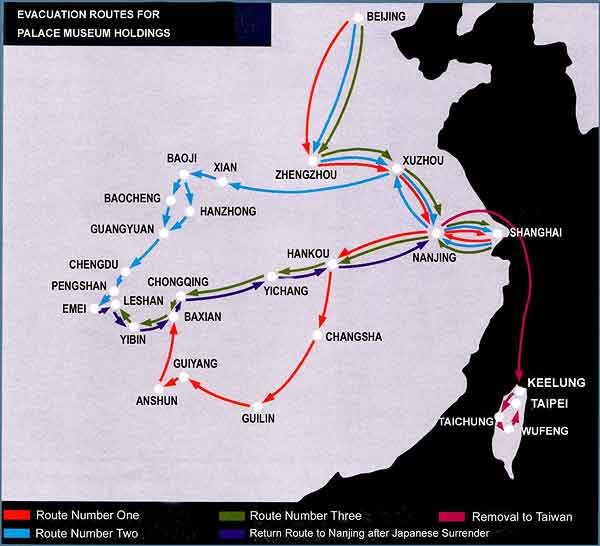

The first moves in the pre-emptive evacuation were clandestine and carried out at night because the government did not want to alarm the population of Beiping, as people would have taken it as a sign that the government was preparing to abandon the former capital. Some of the museum staff, including Na Zhiliang, travelled to Nanjing to look after the national treasures, which were later transported to Chongqing in Sichuan, on the eve of the conquest of Nanjing by the Japanese in 1937. Most of the valuable items in the collections of both museums were saved from the Japanese in an epic 'long march', the scale of which can best be appreciated on the accompanying map. (Fig. 9)

Fig. 9 Map showing routes along which the collections of the Palace Museum were evacuated

Other scholars remained throughout the war within the Forbidden City, which the Japanese troops refrained from pillaging both at the start of the war and during their eventual retreat. This was possibly out of consideration for Emperor Puyi of Manchukuo, now a puppet of the Japanese, or perhaps it was because the responsible persons of the Government Museum defected to the Japanese. After the Nationalist victory in 1946, the government was more determined than ever to place that institution under the control of the Palace Museum. In 1947, the Government Museum was included within the planning for the Palace Museum, and in 1948 the amalgamation was completed, with the Government Museum effectively subsumed.

The Government Museum's entire collection of objects moved to the south had been given over to the Central Museum (Zhongyang Bowuyuan) in Nanjing, and, in 1949, 852 crates of the finest items in the collection of the Central Museum were selected by the KMT for transportation to Taiwan, while the rest of the objects went to the Nanjing Bowuyuan.

Following the Communist victory in the Civil War and the proclamation of the People's Republic of China by Mao Zedong on 1 October 1949, the new Chinese government moved quickly to ensure that the collections of the Palace Museum be re-assembled and catalogued, and that the museum be enhanced as a symbol of the victory of the Party and the people. Ma Heng, who had valiantly protected the collections from the Japanese and who had also attempted to thwart and slow down the removal of antiquities to Taiwan by Chiang Kai-shek, remained Director of the Palace Museum. [BGD]

References:

Aisin-Gioro Puyi, WJF Jenner tr., From Emperor to Citizen: The Autobiography of Aisin-Gioro Puyi, Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1986 reprint ed..

Chang Li-sheng, 'The National Palace Museum: A History of the Collection', Wen Fong and James C. Y. Watt, eds., Possessing the Past, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1996.

Duan Yong, 'Guwu Chenliesuo de xingshuai ji qi lishi diwei shuping' (A critical outline of the rise, decline and historical position of the Guwu Chenliesuo), Gugong Bowuyuan yuankan (Journal of the Palace Museum), Beijing, 2004:5, pp.14-39.

Duan Yong, 'Wuying Dian yu Guwu Chenliesuo' (Wuying Hall and the Government Museum), Zijincheng (Forbidden City), Beijing, 2005:1, pp.53-61.

Jeannette Shambaugh Elliott, David Shambaugh ed., The Odyssey of China's Imperial Art Treasures, Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2005.

Johnston, Reginald F., Twilight in the Forbidden City, London: Gollancz, 1934.

Li Dezheng, Su Weizhi and Liu Tianlu, Baguo Lianjun qin Hua shi (History of the invasion of China by the Allied Expeditonary Army), Jinan: Shandong University Press, 1990.

Shan Shiyuan, The Story of the Imperial Palace and its Buildings, Beijing: New World Press, 2005.

Shu Jun ed., Zhongnan Hai lishi dang'an (The historical archives of Zhongnan Hai), Beijing: Zhonggong Zhongyang Dangxiao Chubanshe, 1997.

Wan Yi ed., Gugong cidian (Gugong dictionary), Shanghai: Wenhui Chubanshe, 1996.

Zheng Xinmiao, 'Gugong xueren erti' (Two Gugong scholars), Gugong xuekan (Journal of Gugong Studies), Beijing: Zijincheng Chubanshe, 2005:2, pp.8-25.

|

Reproduction of the cover of the earliest published guidebook of the Guwu Chenliesuo (Government Museum).

Reproduction of the cover of the earliest published guidebook of the Guwu Chenliesuo (Government Museum).

Reproduction of the cover of the earliest published guidebook of the Guwu Chenliesuo (Government Museum).

Reproduction of the cover of the earliest published guidebook of the Guwu Chenliesuo (Government Museum).