|

|||||||||

|

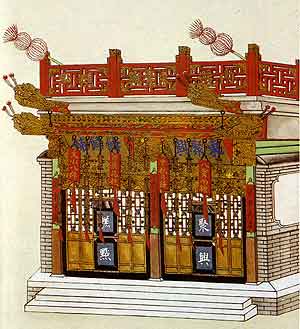

FEATURESBeijing Halal Fig. 1 This old print shows a scene of Qianmen Dajie in the first half of the 19th century. "The flavour of the capital" (Jingwei'r), a term that covers everything with that particular Beijing touch, can also be taken to refer to the particular cuisine of the capital. It developed as one of China's distinctive major regional cooking styles over the course of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) and the Republican period (1912-1949). (Fig. 1) Beijing cuisine represents an amalgam of Chinese halal foods, imperial Manchu culinary refinement and Shandong regional cooking, or Lu cai.  Fig. 2 Cuimahua ("crispy braided horse's tail") is a crunchy, sweet pastry that originated in the halal kitchens of Tianjin and became popular in Beijing during the Republican period.  Fig. 3 Reproduction of a 19th century sign that hung outside a typical halal restaurant in Beijing. The sign is surrounded by calabash vines and the central motifs include a vase of flowers and a teapot. The inscription reads "Qingzhen gujiao" (The Pure Ancient Religion). In the Qing dynasty, the Zhili region, the directly administered territory surrounding the capital, including Tianjin (Fig. 2) in the east and such far-flung centres as Chaoyang, Chifeng and Baoding, shared a border with Shandong. Given Shandong's domination over transport routes to the capital from the south, it is not surprising that Beijing cuisine assimilated Shandong's two main schools of cooking—the eastern school (from the Jiaodong area around Qingdao) and the western school from Jinan and Dezhou, the latter being two major Muslim centres. Dezhou is best known for a variety of duck that, developed and enhanced by chefs in Beijing, would become kaoya ("Peking duck"), the baked and fatty fowl with crispy skin served with thin pancakes, shallots and a sweet salted bean paste (tian majiang) that is synonymous with Beijing. Halal cuisine (qingzhen cai) (Fig. 3) has a long history in China, but the term qingzhen, also the central element in the Chinese term for "mosque" (qingzhen si), originally had no relationship with Islam. In the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127 CE), "qingzhen" sometimes connoted aesthetic purity and refinement, but it was only in the late-Ming and early-Qing periods that qingzhen acquired final definition from prominent Chinese Muslim scholars, displacing rival terms such as qingjing and qingjiao. Dietary practices are, of course, integral to Islam, and China has had halal food as long as it has had followers of Islam, even though different interpretations of what constitutes halal can be traced back to various central and western Asian ethnic groups and religious schools. Moreover, many foods introduced to China from central Asia, including many of the most popular fruits, spices and condiments, predated or were contemporary with the introduction of Islam. They were later readily incorporated into Chinese halal cuisine as it developed over time.  Fig. 4 "Portrait of the Fragrant Concubine in Armour" (Xiang Fei rongzhuang xiang), from the collection of the Palace Museum. This painting is sometimes attributed to the court painter Giuseppe Castiglione.  Fig. 5 Boluofan, Chinese pilaf, based on a Xinjiang dish, similar to the gulunqi said to have been eaten by the Fragrant Concubine in the imperial palace of the Qianlong Emperor. In the Mongol-Yuan dynasty (1206-1368), halal cuisine had grown to encompass a substantial number of dishes, many of which were introduced to the palace where Persians and other Muslims played a significant role. Bai Jianbo, China's leading scholar on the subject of halal cuisine and its history, writes that by the late-Yuan and early-Ming, qingzhen foods formed a distinct element in "popular" cuisine and an encyclopaedia of food from that period, entitled Jujia biyong shi lei quanji (Categories of essential eating for families), devotes an entire chapter to "foods of the Muslims". Throughout the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing dynasties, Muslims spread throughout China. Bai also notes that a number of Chinese cities in the Qing dynasty, and especially in the 19th century, had renowned halal restaurants that catered to Muslims and locals: Shenyang (in today's Liaoning province),Taiyuan (Shanxi), Anqing (Anhui), Xi'an (Shaanxi), Baoding (Hebei), Laohekou (Hubei), Kaifeng (Henan), Nanjing (Jiangsu), Changsha (Hunan) and Tianjin.  Fig. 6 Xinhuamen is the name today for the reconstructed Baoyue Lou, the residence of Xiang Fei on the southern perimeter of the Qing Imperial City. Remodelled in the early Republic, it is now the formal, southern entrance to the Sea Palaces (Zhongnan Hai), the seat of Chinese government. Qing palace cuisine (Qinggong yushan) also contained halal dishes, especially from the Qianlong reign (1736-1795) onwards. The peripatetic habits and multinational diplomacy of the Qianlong Emperor brought halal snacks and dishes to the attention of the palace chefs. The reported arrival at the palace in 1760 of a Uyghur concubine from Turkestan, known to Chinese history and legend as Rong Fei or Xiang Fei (the Fragrant Concubine, Fig. 4), helped promote halal cuisine at the court. Her Uyghur Islamic dietary regimen was guaranteed by her cook, Nurmat, brought to Beijing from Turkestan, and among his dishes, cited in a Chinese language source, were gulunqi (rice pilaf) (Fig. 5) and difeiyaze (a dish fried with onions). Culinary adjustments, conforming to Uyghur halal dietary practices, were also made for her at palace banquets, and a court menu dated 24 September 1779 notes the inclusion in her morning repast of youxiang, a type of salted cake made using eggs and fried in sesame oil. In Uyghur this delicacy is called poxkal. The Fragrant Concubine was housed in Baoyue Lou (Fig. 6) on the southern perimeter of the palace walls, and, to alleviate her homesickness, the Qianlong Emperor is said to have authorised the construction of residences and restaurants for an Islamic garrison and community outside her residence on its southern side, within her sight. Fangwai Guan, an Islamic-themed marble building in the Western Palace (Xiyang Lou) compound at the Yuanming Yuan, north-west of Beijing, is also said to have been constructed for the Fragrant Concubine.

Fig. 7 Youxiang, buns of the kind once supposedly made for the Fragrant Concubine in the Qianlong reign, are here being prepared for a Sufi festival in Zhangjiachuan, Gansu province. [AHG]  Fig. 8 Youxiang buns ready to serve. [AHG] When the emperor received Islamic envoys and other visitors, the court chefs would prepare a "complete lamb banquet" (quanyangxi), at which every part of the lamb would be served. "Complete banquets" (quanxi) were a Manchu-Han court banqueting tradition. For the halal complete banquet, the tables were covered with blue cloth and the characters qingzhen were cut from white cloth and placed against the blue background. Many popular halal dishes served at palace banquets, including congbao yangrou (griddle-fried lamb with shallots), zhima liji (sesame "eye" of lamb or beef), guoshaoji (pot-roast chicken) and zha niupai (fried beef ribs), came to be served at qingzhen restaurants in Beijing, according to Bai Jianbo, as did a number of palace halal snack foods, such as qiegao (sliced glutinous rice cake) and fenggao ("honeycomb" steamed bread).  Fig. 9 A Republican-period photograph from Beijing shows a kerbside Hui food vendor with an impressive range of brass kitchen equipment. Halal cuisine, dominated by lamb and beef dishes, rose to form one of the mainstays of Beijing cuisine during the closing years of the Qing dynasty and throughout the Republican period, when it was popular and promoted commercially. Halal cuisine in Beijing catered to both ends of the market—collective eating in the context of the grand banquet, rightly acknowledged as one of the delights of Chinese life, and "snack foods" (xiaochi), the fast food essential for the smooth running of a major metropolis. (Figs. 7 and 8) Innovations in patrician or residential dining were often purloined from the new tastes sampled on the street at the many plebeian food outlets that brought to Beijing flavours that sustained a populace of itinerants from throughout Zhili who ensured that the capital had a constant supply of fuel, salt, food, clothing and the other essentials of daily life. (Fig. 9)  Fig. 10 A 19th-century photograph of the eastern entrance to Xiheyan lane in the Qianmenwai district. The sign of the Mansan Yuan halal restaurant can be seen in the right foreground.  Fig. 11 Image of Baishun Zhai Naicha Pu from a late-19th century print. This Beijing eatery served milk tea (naicha), and had a clientele composed of Mongols, Manchus, Uyghurs and Huis. Catering to the high end of the market and emulating palace fare, a number of major lamb and beef qingzhen restaurants were established in Beijing's Qianmenwai district, (Fig. 10) where the city's entertainment venues were also concentrated. Many of these had flowery epithets evoking harmony, conviviality, leisure and even luxury, and the buildings themselves were designated with terms used for villas or palatial buildings: Yuanxing Tang (Hall of Original Flourishing), Youyi Cun (Another Village), Liangyi Zhai (Double Vantage Studio), Tonghe Xuan (Harmony Studio), Tongyi Xuan (Harmonious Vantage Studio), Xiyu Guan (The Western Regions Hostelry), Xisheng Guan (Hostelry of the Western Prophet), Qingyan Lou (Hall for Propitious Banquets), Cuifang Yuan (The Garden of Selected Fragrances), Changyue Lou (Joyous Hall), Youyi Shun (Further Good Fortune), Tongju Guan (Hostelry of Harmonious Cohabitation, also known as Xianbing Zhou), and Dong Enyuan Ju (The Eastern Residence of Original Kindness). Halal eating outlets were not, however, limited to the Qianmenwai area where all strata of society sought diversion. Donglai Shun (literally, "coming East has been felicitous") was located in the covered Dong'an Market in Wangfujing, Xilai Shun was located on Western Chang'an Boulevard, and Ruizhen Hou of the Republican period was located near the southern walls of the Forbidden City in what today is called today Zhongshan Park (formerly Central Park).  Fig. 12 A late-19th century postcard showing a photograph of a camel train outside the walls of Beijing.  Fig. 13 Shouzhua yangrou is a Hui variation of what was originally a Uyghur dish. Qingzhen cuisine reflected culinary fashions in the capital and its introduction was undoubtedly driven by all strata of society, but perhaps overwhelmingly by merchants, traders and transport workers whose well established "ethnic" networks first introduced to the denizens of the imperial capital the tastes that came with the trade in tea, horses, salt and grain from, and via, Shandong, Hebei, Shanxi, Shaanxi, Gansu, Mongolia, Qinghai and beyond. (Fig. 11) No mode of transport perhaps more evokes historic Islam than the camel train, and even into the 1970s camel drivers could still be sometimes seen in the areas of Beijing beyond the city. (Fig. 12) All major cities reflect their reach, but Beijing was the centre of a vast empire that eventually blended with the Islamic world to its far north-west. (Fig. 13)  Fig. 14 The brass huoguo (hot-pot) fired with charcoal is the traditional implement for eating the Beijing winter favourite shuan yangrou. Despite the distinction between xiaochi (snack) outlets and more luxurious establishments, many of the leading halal Beijing cuisine restaurants began modestly. Donglai Shun, for example, traces its origins back to the 19th century when a Muslim Hui cook called Ding began selling halal baitang zasui (lamb tit-bits in broth), zamian (green grain noodles) and dabing (fluffy, dry deep-fried bread) at a stall (fantan) in the Dong'an Market. His fare proved so popular and inexpensive that he was forced to expand, and began to cater to his clientele from a fanpeng, benches and stools set up under an awning, and then moved in 1912 into a grey tiled establishment of several rooms, but still inside Dong'an Market, which he called Donglai Shun Yangrou Guan. Donglai Shun became very popular among Manchu, Mongol and Hui customers, and in autumn his shuan yangrou ("lamb hot pot") attracted an even wider following, the meal eventually becoming an integral part of Beijing cuisine. (Fig. 14) Even when Donglai Shun was thriving, Mr Ding catered to his clientele from the stall he continued to man at the front of the restaurant, selling zasui tang (soup with tit-bits), laobing (griddle buns) and niurou tangmian (beef noodles in broth). Because of limited space at Dong'an Market, he set up another restaurant on Western Chang'an Boulevard which he called Xilai Shun. Here patrons could hold banquets and Peking duck became a specialty at the new premises.  Fig. 15 Chao geda, small fried balls of dough cooked with lamb or beef.  Fig. 16 Dongjuxong Bobopu was a well-known laozihao cake and pastry shop located in the Andingmennei district of Beijing in the late 19th century.  Fig. 17 Aiwowo, "love drops", a halal xiaochi popular in Beijing from the Ming dynasty onwards. In the later years of the Qing dynasty, two other Hui restaurants also opened in Li Tiegui Xiejie (Li Tiegui Diagonal Road) in Qianmenwai—Liangyi Xian and Tonghe Xian. These were frequented by performers from the Peking Opera theatres in the vicinity, many actors being of Hui ethnicity. Famous performers of the time who dined there included Cheng Lifang, Cheng Yanqiu, Li Shaochun and Yu Shuyan. In autumn and winter, kaorou (roast meat) was a simpler dish to serve than shuan yangrou (scalded or instant-boiled mutton served in a steamboat or hot-pot). Usually made from beef, it was served at tables for two at a restaurant called Kaorou Yuan. Two other small restaurants established by Hui entrepreneurs were Xian'rbing Zhou, which sold xian'rbing (flat griddle cakes with meat and vegetable filling), and Mujiazhai, which served chao geda, fried small strips of dough served with either lamb or beef. (Fig. 15) At first, these were cheap eateries that catered to labourers but the quality of their food soon attracted a wealthier clientele.  Fig. 18 This photograph shows bowls with condiments lined up to be filled with baodu, a halal tripe dish served in many establishments in old Beijing. The early halal lamb restaurants served dishes that had a "heavy" flavour with thick sauces, containing large quantities of qian (Gorgon euryale, Eurayale ferox), a type of Chinese starch often mixed with bean powder, arrowroot and caltrop. Shandong cuisine and southern cooking introduced to Beijing introduced a fondness for lighter soup-like stews, so that halal lamb in the capital came to be served up in hotpots or in lighter soups. Halal shuan yangrou and kaorou thus represented an amalgam of cuisines from many national groups and regions.  Fig. 19 A plate bearing Jingdong roubing, a type of meat-filled halal pancake that comes from east of Beijing. Another halal lamb specialty of Beijing was shao yangrou (grilled lamb), which in the 19th century was the centrepiece for banquets at the restaurant called Yuesheng Zhai. Shao yangrou was originally prepared according to an elaborate method that included 24 different herbs and spices, and various stages in the cooking process—suspending the meat in boiling water, compressing the meat, stacking the meat, frying the meat and simmering the meat. Finally the dish was deep-fried, and the resulting dish was tender and rich in taste.  Fig. 20 A halal roadside restaurant east of Beijing in Dachang Hui Autonomous County, Hebei province, that specialises in Dachang or Jingdong ("east of Beijing") style dishes, including Jingdong roubing. These lamb stews saw further innovation. Fish was introduced to lamb soup, for example, to produce boyu, a delicacy served at Guanghe Ju for a century. The fish and other ingredients were said to have been introduced from Fuzhou, but the use of a thin lamb stew was a Beijing innovation. In the Republican period, many of the "classic" or "established" restaurants and stores (called laozihao) claimed hoary pedigrees (Fig. 16), and a number were halal restaurants. For example, Kaorou Yuan, which specialised in both roast beef and lamb, claimed to have been established in 1686. However, sources on the histories of many famous name restaurants in Beijing are often in conflict, whether because of family feuds or "imitators'. Yuesheng Zhai, specialising in shao yangrou, not to be confused with a restaurant of the same name that served jiang yangrou (pickled lamb), claimed to be able to trace its origins back to 1775. Kaorou Ji at Hou Hai, which specialised in both deep-fried beef and lamb, was established in 1848, and Donglai Shun, specialising in shuan yangrou, in 1912. The concept of laozihao, or brand-name establishments, appeared around 1910, and most of the famed restaurants were concentrated in the Qianmenwai district, as well as in Dongsi, Xidan, Gulou, Huashi and Dengshikou. To respond to competition and so as to operate all year around, many diversified from their original single speciality dish or dishes, especially if the dish was seasonal. During the Republican period, many laozihao restaurants from southern China made successful inroads into the Beijing market, but outside Beijing the only laozihao from the capital that flourished with "branch" outlets in southern cities were those that specialised in lamb dishes.  Fig. 21 Shaobing, a type of round bun coated with sesame seeds, is a perennial favourite in China. This type is called honglian shaobing.  Fig. 22 Zhima yangrou, sesame lamb, is a long-standing favourite halal dish in Beijing. The enthusiasm for halal restaurants in Beijing continued through the 1950s and into the early 1960s. One of Tianjin's most famous halal lamb restaurants, Hongbin Lou, founded in 1853, set up a Beijing branch in 1955. The move was prompted by a proposal made by Premier Zhou Enlai, according to the publicity for the restaurant prepared by its present owners, Jude Huatian Holding Co. Ltd. Following its relocation as one of the major restaurants serving Beijing and Tianjin halal cuisine, Hongbin Lou was patronised by Chinese leaders and prominent Party members. In 1963, China's pre-eminent official academician Guo Moruo penned a poem celebrating the restaurant, and the poem in his stolid calligraphy is now displayed in the foyer of the premises in Beijing's Xicheng district, where Hongbin Lou relocated in 1998. Today its menu still boasts some of the pillars of halal Beijing cuisine, including halal kaoya (Peking duck), shuan yangrou (scalded lamb) and feiniu huoguo (succulent beef crock-pot). Over the past two decades, Beijing, and China, have experienced a "food revolution'. Restaurants specialising in cuisine from Sichuan, the North-east, Yunnan, Hubei and Hunan, often part of restaurant chains, came to the capital in waves beginning in the early 1980s, while Hakka, Manchu, Tibetan, Korean and Dai cuisine also gained a firm foothold in the capital in the 1990s. Despite the popularity of Lanzhou noodles and Xinjiang eateries in Beijing until the mid 1990s, most of the recent innovative cuisine has not been halal-inflected. As well as new types of cuisine, novel ingredients have also been included in traditional dishes. Shuan yangrou, for example, can now be served with previously unknown accompaniments, such as potatoes, radish, a vegetable called youmaicai, manufactured "crab sticks" and non-halal ingredients, while every variety of hot-pot cooking can now be found in Beijing. These domestic innovations are matched by offerings of international cuisine, ranging in origin, or at least inspiration, from Thailand, India and Japan, to Brazil, Argentina, Azerbaijan and Russia. American-style fast food outlets and supermarkets selling complete packaged meals also abound. It is little surprise that qingzhen food is now less integral to the concept of Beijing cuisine, which itself is no longer dominant in the nation's capital.  Fig. 23 The finest halal green noodles (zamian) still come from Raoyang county in Hebei province. Large areas of the Qianmenwai district of Beijing are slated to be rebuilt in toto, and many of Beijing's laozihao halal establishments, such as Baodu Feng and Yuesheng Zhai, will be torn down. To pre-empt the demolition crews, residents have been flocking to the cramped restaurants where Beijing cuisine asserted its ascendancy a century ago. Reporting on the demise of this eating district, Beijing Youth Daily, in its 19 February 2006 issue, provided a new dimension to the concept of China's intangible cultural heritage by asking readers whether Beijing's "intangible specialty foods" (feiwuzhi techan) will taste the same when served up in the gleaming fast food Beijing style diners that will rise on the ruins of the old-time eateries. Some of our most evocative cultural memories are those aroused by food, and, by introducing their dishes to Beijing, Chinese Muslims not only kindled memories of their own remote homelands but provided a new dimension to culinary experiences peculiar to the Chinese capital. [BGD] APPENDIX: HALAL-RELATED SNACKS AND DISHES IN BEIJINGAIWOWO 艾窝窝 aka 爱窝窝 ("love drops") (Fig. 17) BAODU 爆肚 (lamb tripe in sauce) (Fig. 18) CONGBAO YANGROU 葱爆羊肉 (griddle-fried lamb with shallots) JIANG YANGROU 酱羊肉 (pickled lamb) QIEGAO 切糕 (sliced glutinous rice cake) ROUBING, XIAN'RBING, MENDING XIANRBING

肉饼,

馅儿饼,

门钉馅儿饼

(griddle lamb pancakes) (Figs 19 & 20) SHAOBING 烧饼 (sesame seed buns; also called zhima shaobing) (Figs 21 & 22) TANGMIAN JIAOZI 汤面饺子 (dumplings made from boiled flour) YANGTOU ROU 羊头肉 (lamb's head meat) YANG XIEZI 羊蝎子 / 羊羯子 (lamb spine) ZAMIAN 杂面 (green noodles) (Fig. 23) ZHU YANG ZASUI 煮羊杂碎 (lamb gizzard soup) References:Bai Jianbo, Qingzhen yinshi wenhua (The culture of halal food), Xi'an: Shaanxi Lüyou Chubanshe, 2000, 526 pages. Jin Lin, "Fengwei xiaochi", in Zhongguo Renmin Zhengxie Huiyi and Beijing Shi Weiyuanhui Wenshi Ziliao Weiyuanhui eds., Beijing wangshi tan (Talks on aspects of Old Beijing), Beijing: Beijing Chubanshe, 1988, pp.9-12. Jin Shoushen, Lao Beijing de shenghuo (Life in Old Beijing), Beijing: Beijing Chubanshe, 1989, 424pp. This work introduces the complex history of shao yangrou. Millward, James A., "A Uyghur Muslim in Qianlong's court: The meaning of the Fragrant Concubine", The Journal of Asian Studies, Michigan: Ann Arbor, vol. 53, no. 2 (May 1994), pp.427-458. Xu Hairong ed., Zhongguo yinshi shi (A history of Chinese cuisine), Beijing: Huaxia Chubanshe, 1999, 6 vols. Yin Runcheng, "Fengwei fanguan" (Restaurants with local flavour), in Zhongguo Renmin Zhengxie Huiyi and Beijing-shi Weiyuanhui Wenshi Ziliao Weiyuanhui eds., Beijing wangshi tan (Talks on aspects of Old Beijing), Beijing: Beijing Chubanshe, 1988, pp.9-12. |