|

|||||||||

|

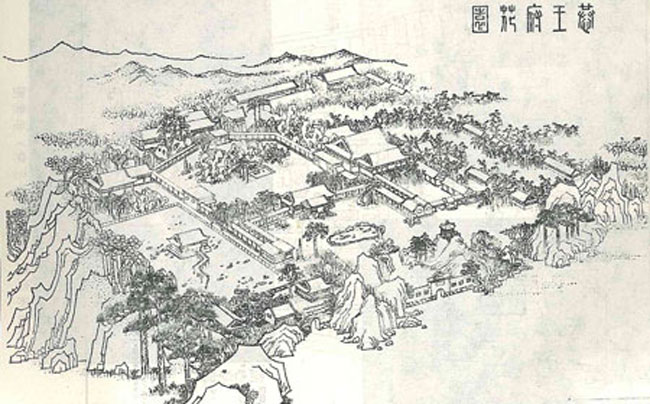

FEATURESPrince Gong's Folly An impression of the Attached Garden of Prince Gong's Mansion. Source: Zhou Ruchang, Searching for the Real in the Red Chamber (Honglou fang zhen), Beijing: Huayi Chubanshe, 1998, illustrations. Prince Gong (1833–98), the prince counsellor who helped guide the Qing dynasty through some of the most calamitous events of the nineteenth century, was also China's first 'foreign minister'. He lived in a palatial residence near the Sea Palaces, north-west of the Forbidden City in Beijing. That residence, now known as Prince Gong's Mansion, is the largest and best-preserved publicly accessible princely seat (wangfu) in the Chinese capital. Originally the home to Heshen, one of the most perfidious and corrupt of Manchu Qing officials, it is also thought by some to have inspired the labyrinthine garden residence that provides the mis-en-scène for China's greatest novel, The Dream of the Red Chamber (Honglou Meng, also known as The Story of the Stone) by Cao Xueqin, a complex tale of a family dynasty, its vicissitudes and the uncertain fortunes of individuals in late-traditional China.[1]  Fig.1 The 'Jesuit baroque' entrance to Prince Gong's garden. [Photo: GRB] Fig.1 The 'Jesuit baroque' entrance to Prince Gong's garden. [Photo: GRB]

The spacious gardens north of the living quarters of the palace were redesigned during Prince Gong's residence, and they include a number of 'novelties' or 'follies'. Follies are well known from eighteenth-century European garden design as structures that, although often elaborate and expensive, have no obvious or practical function. They are garden features that do, however, above all demand attention. Some follies are built to delight or bedazzle, others to intrigue and divert. Often their presence in a garden landscape—sometimes in the form of archways, gates or romantic ruins—provides a visual diversion or an ironic commentary on the main residence or its architectural motives.  'Elm Pass', Prince Gong's garden. [GRB] 'Elm Pass', Prince Gong's garden. [GRB]

In Prince Gong's garden there are two follies that also serve a function, for they provide alternative entries to the enclosed garden itself. One of them is a large Western-style gate built in what has been called the Jesuit-baroque of Beijing (Fig.1); the other, a crenallated entrance known as the Elm Pass 榆關, was whimsically referred to by Prince Gong's descendants as the family's very own 'Half-a-li Great Wall' (banli changcheng 半里長城), a play on wanli changcheng, or 'Ten thousand li Great Wall'.[2] (Fig.2) IToday, Prince Gong's Palace and its Adjacent Garden (Gong wangfu ji huayuan), as it is officially called, is the most celebrated of the princely residences that remain in the former imperial city. Although seventy-four mansions were listed in Beijing guidebooks in the 1920s, and nearly fifty survived into the 1950s, few are still extant.[3] At the time of writing, even Prince Gong's palace is only partially accessible to the public for, after some fifty years of occupation by various institutions and arms of government, the main residence is undergoing restoration (or, more properly, rebuilding), like so much of 'Old Beijing', in preparation for the 2008 Olympic Games.  Fig.3 Overview of the Garden of Perfect Brightness (Yuanming Yuan) and surrounding garden palaces and villas (by Jin Xun, 1924, reprinted as Yuanming Yuan yuanmao tu [The original appearance of the Garden of Perfect Brightness], Beijing: Xueyuan chubanshe, Beijing, 2005. Fig.3 Overview of the Garden of Perfect Brightness (Yuanming Yuan) and surrounding garden palaces and villas (by Jin Xun, 1924, reprinted as Yuanming Yuan yuanmao tu [The original appearance of the Garden of Perfect Brightness], Beijing: Xueyuan chubanshe, Beijing, 2005.

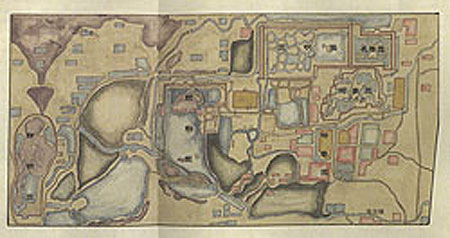

It is important to appreciate the private garden of late imperial China as, among other things, a place of hubristic imitation and discrete ostentation. Throughout the history of the place, what is known as Prince Gong's palace has enjoyed an uncanny symmetry of fate with the Garden of Perfect Brightness (Yuanming Yuan, the focus of China Heritage Quarterly, issue 8, December 2006), and the palaces and pleasances connected to it. That garden, the remains of which are now a public park to the north of Peking University in the Haidian district, was from the early years of the Yongzheng reign (1723–35) until its devastation by an Anglo-French army in 1860, a de facto seat of government of imperial China. The Qing emperors had a predilection for living outside the confines of the Forbidden City in the centre of Beijing, and they created a replica of the state administration far beyond the city walls at the Garden of Perfect Brightness and spent months at the Imperial Mountain Lodge at Chengde (Jehol), north-west of Beijing, and the hunting grounds beyond. The requirements of court attendance and other key ceremonial activities obliged the nobility and leading ministers to build residences of their own in proximity to the Garden of Perfect Brightness.(Fig.3) The gardens of Tsinghua and Peking universities,[4] which form a major feature of those two campuses today, were originally parts of the numerous garden residences of the Qing ruling class. In those sequestered gardens, some grandees went so far as to indulge in architectural lèse-majesté by having buildings created in imitation of those enjoyed by their imperial master.  Fig.4 Weiminghu Lake, Peking University, formerly part of Heshen's Shuchun Yuan. [Photograph by Lois Conner, 1999] Fig.4 Weiminghu Lake, Peking University, formerly part of Heshen's Shuchun Yuan. [Photograph by Lois Conner, 1999]

During the heyday of the Garden of Perfect Brightness, in the Qianlong reign (1736–95), the emperor's chief minister Heshen created the Shuchun Yuan, a splendid residence for himself immediately south of the royal estate.(Fig.4) Its remains can be seen at the picturesque Weiminghu Lake of Peking University. It is this lakeside demense that, among other things, played a role in Heshen's eventual downfall. IIIt is said that Heshen (1750-1799) rose to the height of power from relative obscurity as a result of his comely appearance and manner. He would become so enamoured of his unassailable authority that eventually he gave concrete expression to his imperial airs. At Shuchun Yuan 淑春園 he had a large ornamental lake and island built. When Heshen was arrested on the orders of the Jiaqing emperor (r. 1796-1820), son and successor to Heshen's patron Qianlong, it was found that the lake's design and kiosks mimicked too closely those of the Pengdao Yaotai 蓬島瑤台 islands in the Lake of Plenitude at the emperor's Garden of Perfect Brightness to the north.[5] The Jiaqing emperor had taken an intense dislike to his father's favourite and he was outraged by Heshen's brazen corruption and presumption. The minister's crimes in design, however, did not end with his country estate. For in his Beijing mansion not far from the Forbidden City and near Qianhai Lake, he had had the temerity to order the construction of exact copies of palace buildings. One of these, the Hall of Delighted Longevity (Leshou Tang) faithfully recreated the elaborate interior appointments of the Hall of Serene Longevity (Ningshou Gong), a place for imperial birthday banquets, and part of the 'mini Forbidden City' built for the Qianlong emperor for use in his later years. During the investigation into Heshen's crimes against the throne, the disgraced minister revealed that he had ordered a trusted eunuch retainer to make detailed sketches of the palace in question, right down to the decorations on the marble pillar bases, which featured carved drums and lotuses, patterns strictly reserved for the embellishment of the emperor's quarters.[6]  Fig.5 Prince Gong. [Photograph by Felice Beato, collection of Michael G. Wilson, Santa Barbara Museum of Art] Fig.5 Prince Gong. [Photograph by Felice Beato, collection of Michael G. Wilson, Santa Barbara Museum of Art]

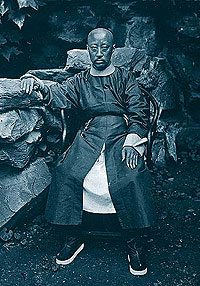

These architectural acts of audacity constitute the thirteenth of the twenty great crimes of Heshen. To have such buildings constructed for personal use defied the strict codes of the Qing court and, as the indictment issued by the Jiaqing emperor reads, they were 'insolent in the extreme and in breach of all due propriety'. In gleeful high dudgeon—for the emperor was anxious to rid himself of this dangerously powerful minister—it asks, 'What exactly was his intention?'[7] However, so exquisite were the details and arrangement of Heshen's Hall of Delighted Longevity that, despite the breach of imperial protocol and the strict building regulations of the court, the courtyard and its palatial apartments remained untouched long after their presumptuous builder's demise.[8] Both the Shuchun Yuan and Heshen's city residence were confiscated and allocated to other members of the nobility. Heshen himself was treated with a measure of lenience, being allowed to commit suicide in 1796. Half a century later the grand mansion at Qianhai Lake would eventually be presented to a young and able member of the imperial family by the name of Yixin. The younger brother of the Xianfeng emperor and grandson of Heshen's imperial persecutor, Yixin would also have a political career that waxed and waned according to the pleasure of the throne.(Fig.5) When his brother Yizhu (1831-1861) ascended the dragon throne under the reign title of Xianfeng ('prosperity for all') in 1850, Yixin was elevated to the status of prince and given the title Prince Gong (恭), the 'respectful'. He was known for his martial ability—something highly prized by the Manchu ruling house—and for being an adroit thinker. Upon his father's death many had expected that Yixin would be named successor in the emperor's will. However, his elder brother had ingratiated himself with the dying monarch and, although a far lesser talent, he took the throne. Xianfeng's reign would, however, be marred by prevarication and lassitude that would see the Qing empire brought to the brink of collapse. Although he was not made emperor, Yixin was now a prince of the first rank with all of the privileges and prestige that accrued to that status. In 1852, Xianfeng further rewarded his brother by bestowing upon him one of the most expansive residential compounds in the Inner City of the capital, Heshen's former palace, which henceforth was known as Prince Gong's Mansion.[9] Although it is all but impossible to ascertain what and when changes were made to the mansion, there is evidence that the garden as it now exists dates from the early 1870s, long after Prince Gong had acquired the property and reached the pinnacle of his own power.[10] IIIIn 1860, the Qing empire was faced with a threat that led the emperor and his closest advisers to flee outside the Great Wall to escape the foreign menace. It was an unparalleled moment that turned the history of the wall on its head. Paradoxically, Prince Gong's career would flourish because of this selfsame threat. After consolidating the vast Qing empire through alliances and war with the restive peoples beyond the wall—of whom they had been one originally—the Manchu rulers were now faced with encroachment from an unlikely quarter. In nineteenth-century China, the danger to the empire came not from the north, as it had for the long centuries during which great walls had been constructed by dynastic rulers to protect the Central Plains, but rather from the restive provinces to the south as well as from the most porous border of the empire: the sea. Negotiations with the imperial powers of Britain and France had reached an impasse following the Second Opium War (1856-60). With his grand retinue, the Xianfeng emperor travelled beyond the Great Wall for the last time, on the pretext of engaging in the autumn hunt, and he entrusted Prince Gong with the task of dealing with an Anglo-French army that was now pressing on Beijing. Before the situation could be resolved, the murderous duplicity and arrant incompetence of the emperor and his counsellors led the foreigners—themselves hardly innocent in this latest phase of a decades-long process of aggressive trade and diplomatic demands—to sack the imperial garden palaces outside the capital. Avowedly, it was a strategy employed to teach the conniving Qing court a lesson: in the process the palace buildings of the Garden of Perfect Brightness were looted and the gardens severely damaged, as were the other extensive palaces, hunting grounds and noble residences in the area.[11](Fig.6)  Fig.6 Commemorative plaque at the site of the Audience Hall at the Garden of Perfect Brightness. [Photo: GRB] Fig.6 Commemorative plaque at the site of the Audience Hall at the Garden of Perfect Brightness. [Photo: GRB]

Now remembered in China as a cataclysmic moment of national humiliation that marked the bankruptcy of Manchu Qing rule and dynastic politics, the destruction of the Garden of Perfect Brightness did, however, have the desired effect. It forced the court, advised by Prince Gong, to finalise a settlement with the aggressors. Shortly afterwards, the prince's imperial sibling died at Chengde and, with the connivance of the imperial wives—one of whom would later achieve lasting notoriety as the Empress Dowager, Cixi—Prince Gong helped engineer a coup which resulted in the faction of ministers nominally in charge of the empire detained: their leader Sushun was executed and the others removed from office. Prince Gong now exercised control over the imperial government as prince counsellor (yizheng wang). With his supporters, he launched a self-strengthening movement. Known also as the Tongzhi Restoration, after the reign title of the new minority emperor Tongzhi ('unified rule', reigned 1862–74), this period saw the revival of the fortunes of the dynasty. It was at this time that the guiding philosophy that has informed much of Chinese statecraft ever since found its original articulation at court. If China were to survive as a polity, if it were to maintain its traditions, territorial integrity, social cohesion and take its place in the world, its rulers had to pursue policies that would allow for the enrichment of the state and the strengthening of arms. Initially, the creation of industry and communications networks was not an aspect of this self-strengthening: what was crucial to it was the disavowal of the inward-looking, self-assured and defensive mindset of the past. Prince Gong and his fellows recognised the realities of international power politics and, for the years of the Tongzhi reign at least, they attempted, and were largely successful in pursuing, an energetic engagement with the imperial powers.[12] As prince counsellor, the central figure in practical politics, Prince Gong now enjoyed the imperial authority previously denied him. But his power resided entirely in the throne, the will of which was directed by the two empresses and a young emperor. In the early 1870s, while the country was recovering from disastrous and financially draining local rebellions, war and foreign incursion, the emperor decided to rebuild the luxurious Garden of Perfect Brightness. It was a move that would symbolise dynastic renewal, a project that would wipe away the disgrace visited upon the imperial ancestors who had created the gardens. Furthermore, it would satisfy the increasing hubris and sybaritic needs of the empresses, who had long been deprived of their garden redoubt. However, officials throughout the empire were outraged and they argued that, given the parlous state of the imperial coffers, such a lavish and vainglorious undertaking could prove disastrous. Prince Gong was one of the leaders of the protestations.[13] Following the outcry from the provinces, backed up as they were by Prince Gong, the potentially ruinous project was brought to a halt—although the Empress Dowager Cixi would not be denied a country residence for long. It was at this point that it would appear that Prince Gong had designs on his own garden. IVIt is the two extraordinary entrances to the extensive gardens that Prince Gong now built that occupy us here. Gates, entrances and passes are often thought of as being exclusive, forbidding and unyielding but, as many contributors to this volume have argued, such barriers also often acted as thresholds, liminal zones that mark a place of contact, as well as spaces where difference was dissolved. Entrances and gates are also transit points where, in the case of the carefully designed Chinese garden, living and leisure reach an accommodation. The wall of Prince Gong's garden, which divides earnest living from leisurely comfort (and literary composition), is located behind the courtyard residential quarters of the palace proper. It is punctuated by two entrance-exits, one iconically Chinese, the other fancifully occidental. The foreign-style gate is built in the fashion of what has been called 'Jesuit baroque' (see also 'A Non-Princely Mansion from Qing-dynasty Beijing' in Articles in this issue). It was made in clear imitation of the gates of the peacock aviary found at the Western Palaces of the Garden of Perfect Brightness, a series of imitation-baroque structures created by the Jesuit missionary-courtiers serving the Qianlong emperor. The marble Western Palaces were devastated along with the other gardens and buildings when the Anglo-French forces sacked the area in 1860. However, being made of sturdier materials than the wood and tile common in Chinese construction, the Jesuit buildings remained, even in ruination. To this day, it is those marble ruins that, more than any other part of the vast grounds of the Garden of Perfect Brightness, represent the grand scale of the original palaces and the wantonness of their destruction.  Fig.7 The 'Jesuit baroque' entrance to Prince Gong's garden. [Photo: GRB] Fig.7 The 'Jesuit baroque' entrance to Prince Gong's garden. [Photo: GRB]

It is through this main Jesuit baroque gate that access is gained to Prince Gong's garden.(Fig.7) An inscription over the gateway contains a message to those entering the garden through this doughty portal: 'The silence contains the peace of antiquity' (jing han taigu 静含太古). It is an indication that the visitor was entering a realm far from worldly cares, a place for communion with the abiding spirit of the past. Leaving by this same gate, the inscription the visitor encountered on the other side of the lintel is a reminder of the garden experience: 'The loveliness detains the constant spring' (xiu yi heng chun 秀以恒春).[14] Commentators have remarked that this mock-Western gate is 'a debased, and badly interpreted, baroque, with coarse detail and poor proportions; but nevertheless with a definite charm of its own, that must be seen to be appreciated.'[15] While the Western-style buildings at the Garden of Perfect Brightness remained in ruin—although Prince Gong had, shortly after the sacking of 1860, mischievously suggested that they could be repaired to house Western diplomats—elsewhere in the capital there was something of a vogue for architectural features of European design. Few of these remain today, apart from the gate at Prince Gong's garden, a pair of gates that form an entrance to the rear quarters of the Wanshousi Temple (now situation just inside the West Third Ring Road), a place used as a way-station for the imperial retinue as it travelled to the gardens to the north-west of the city, and another at the Summer Palace (Yihe Yuan—the Garden of Harmonious Longevity), the semi-rural retreat near the Garden of Perfect Brightness that was rebuilt for the Empress Dowager in the 1880s.(Fig.8)  Fig.8 A western-style courtyard entrance at the Summer Palace [Photo: GRB] Fig.8 A western-style courtyard entrance at the Summer Palace [Photo: GRB]

Fig.9 'Elm Pass', the crenulated mini-Great Wall, Prince Gong's garden. [Photo: GRB] Fig.9 'Elm Pass', the crenulated mini-Great Wall, Prince Gong's garden. [Photo: GRB]

Further along, near what is now the tourist entrance to Prince Gong's garden, is another opening in the surrounding wall. It is called Elm Pass (Yuguan), a name with allusions both to ancient 'elm walls' (yusai)[16] and to all that is 'beyond the pass' (guanwai)—that is, the lands that gave rise to the coalition of forces under the Manchus. This gateway consists of the 'Half-a-li Great Wall' crenellated pass, a stretch of the Great Wall in miniature. It is surrounded by carefully arranged Taihu Lake stones, and crowned with a narrow length of crenellated wall that leads past a delicate structure, the Pavilion of Delightful Fragrance, to an erect scholar stone.(Fig.9) The Elm Pass is an explicit reference to the Shanhaiguan Pass, 'the pass between mountains and sea', which is the main gateway pass through the Great Wall at Qinhuangdao in Hebei province. During the last months of the Ming dynasty, as the Manchu forces led by Prince Gong's imperial ancestors were pressing down from the north, this pass, a crucial route into China proper, was guarded by the general Wu Sangui. Wu had protected the pass ably but, as Ming rule tottered, he negotiated an arrangement with the Manchu enemy. He agreed to let the Manchus through the pass to join him in a campaign against a local rebellious army that had occupied the capital of Beijing. But, once the rebels were ousted, the Manchus took the city for themselves and proclaimed their rule over all of China. Thus, at this crucial moment, the Great Walls—those defensive bulwarks refashioned and reinforced over the centuries to keep nomadic peoples, barbarians and warlike marauders at bay—failed due to human miscalculation. By turning the barrier into an open passage, Wu Sangui engineered the final defeat of the Great Wall of China. Henceforth, the walls would become relics: crumbling reminders of futile policies and crippling expense. Prince Gong's folly, the reduced Elm Pass in his garden wall, is thus a private reminder of the rise of the imperial lineage to which he belonged. It also referred to a passageway through the Great Wall that, no longer defensive in nature, remained in active use under the Qing emperors. Particularly during the reigns of the Kangxi and Qianlong emperors, the pass was used as an important way station when the rulers travelled in state 'beyond the pass' to visit their ancestral lands and the original capital of their dynasty at Shengjing, or Mukden in Manchu (present-day Shenyang). There they would pay their respects at the graves of their imperial forebears located outside that city.[17] At the real Elm Pass both Kangxi and Qianlong famously composed poems which both reflect the importance of the place in the history of the Manchu-Qing dynasty and also remark on the builders of the Great Wall. For example, the Kangxi emperor (reigned 1662-1722) wrote: Ten thousand li here to the sea V Fig.10 Prince Gong in repose in his garden around the time of its refurbishment. [John Thompson, Illustrations of China and it's people, vol.1, plate I, London, 1873] Fig.10 Prince Gong in repose in his garden around the time of its refurbishment. [John Thompson, Illustrations of China and it's people, vol.1, plate I, London, 1873]

Prince Gong's folly is a reminder of his heritage; it is also a comment on the Manchu conquest of China. The fact that it was built after the agents representing a new foreign threat had come from the south and taken up residence in Beijing only adds to the piquancy of the structure. Furthermore, along with the European-style gate further to the east in the wall, it resonates with the Garden of Perfect Brightness, the imperial residence favoured by Prince Gong's ancestors, and the reconstruction of which he played a crucial role in preventing.(Fig.10) Not long after he rebuilt his garden in the early 1870s Prince Gong was accused by the throne of impropriety and forced into retirement. For over twenty years he lived at his mansion, writing poetry and enjoying the diversions of his garden which, among other things, contained a large Peking opera theatre with a sumptuous wisteria-decorated interior. He also spent time at his country residence just south of the Garden of Perfect Brightness. Called the Garden of Moonlit Dew (Langrun Yuan), it would play a role in the Boxer Rebellion of 1900 when once more Chinese and foreign forces clashed. The garden was used as a headquarters by German troops, who were in a bloody standoff with the Boxer rebels occupying Zhengjuesi Temple, one of the only remaining structures of the Garden of Perfect Brightness (refurbished in recent years). Today, a lavish neo-traditional complex housing Peking University's China Center for Economic Research is located on the site of the Garden of Moonlit Dew.(Fig.11) It is only a short walk from the remains of Heshen's original country retreat and its impressive lake.  Fig.11 China Center for Economic Research, located on the site of Prince Gong's Garden of Moonlit Dew, Peking University. [Photo: GRB] Fig.11 China Center for Economic Research, located on the site of Prince Gong's Garden of Moonlit Dew, Peking University. [Photo: GRB]

During Prince Gong's forced retirement, the achievements of the Tongzhi Restoration were gradually undermined and the defences built up under his stewardship poorly maintained. As she reached the height of her power and influence, the Empress Dowager finally had one garden palace rebuilt. The Summer Palace contains not one short length of mock Great Wall but six wall-like passes and gates.(Figs 12&13)  Fig.12 'Dawn Light Gate Tower' (Yinhui chengguan), Summer Palace. [Photo: GRB] Fig.12 'Dawn Light Gate Tower' (Yinhui chengguan), Summer Palace. [Photo: GRB]

The Summer Palace also features a folly well known to Chinese and international travellers: a large stone boat (shifang).(Fig.14) Although a reconstruction of an earlier fancy, the boat is regarded by many as a pointed reminder that funds that should have been spent on building China's naval defences—the maritime 'Great Wall' of the modern age—were diverted to this magnificent garden palace. And it was just as the new Chinese navy faced its most crucial test in a war with Japan in the 1890s that Prince Gong was restored to office in the hope that he could salvage the situation. But China suffered a crushing, and humiliating defeat. Unable to reverse the fortunes of the dynasty this time, the prince died shortly afterwards, in 1898.[18] VIThe history of Prince Gong's mansion during the twentieth century is a somber one. In the last years of the Qing dynasty, which would only outlast Prince Gong's death by a dozen years, the mansion and garden were bestowed upon Puwei, Prince Gong's second son. During the years of the Republic of China (1912–49), parts of the once lavish residence and gardens were gradually sold or rented by the prince's penurious descendants to pay off debts. In 1937, the Fu-Jen Catholic University, which had built its main campus at Prince Tao's Mansion (Tao beile fu) to the west of Prince Gong's garden, expanded and established their women's campus there and created a school of fine arts in the grounds.[19] In the early years of the People's Republic of China, founded in 1949, the Communist Party-run government was hard pressed for both residential and office space. Many private residences were requisitioned to house the leaders and agencies of the new people's government. Prince Gong's Mansion, with its many courtyards, halls and living quarters, was divided among a number of state organs. During the long years of Maoist socialism it effectively disappeared from the map of Beijing, becoming literally a 'secret garden'.  Fig.13. 'Purple Cloud Gate Tower' (Ziqi donglai chengguan), Summer Palace. [Photo: GRB] Fig.13. 'Purple Cloud Gate Tower' (Ziqi donglai chengguan), Summer Palace. [Photo: GRB]

Initially, the loggias, halls, corridors and pavilions of the garden were converted into makeshift, although well-appointed, living quarters for the leaders of the political department of the Ministry of Public Security and the Political Protection Bureau. From 1950 to 1955, these dormitories were also used by a handful of Soviet cadres; the commissars had been assigned to help establish the fledgling nation's secret service. As Soviet influence waned the buildings were reoccupied by China's own security personnel and their families.[20] Later still, much of the palatial residence was reallocated to the Chinese Academy of Music and the Art and Literature Research Institute of the Ministry of Culture, members of which would play a crucial role in launching China's post-Cultural Revolution avant-garde art movement in the 1980s.[21] The eastern corridor of courtyards, however, remained residences for the Ministry of Public Security. To accommodate the needs of the various organisations allocated space in the mansion, some buildings were demolished and courtyards built in. However, the gardens remained relatively unscathed.  Fig.14 The Stone Boat (shifang), Summer Palace. [Photo: GRB] Fig.14 The Stone Boat (shifang), Summer Palace. [Photo: GRB]

The avowed, although unevenly applied, policy to restore the cultural heritage of the capital initiated after the Cultural Revolution led to a partial restoration and preservation of the mansion. In 1980, in the early post-Mao era, John Minford, a sinologist and translator of the last forty chapters of the mid Qing author Cao Xueqin's celebrated novel The Story of the Stone, encountered the place. He found a dishevelled landscape in which the romantic imagination confronted the secretive power of the state (see his essay).[22] Shortly before Minford's visit, the leading expert on the novel, Zhou Ruchang, had published a monograph in which he claimed that Prince Gong's Mansion and gardens (or rather the form they took in Heshen's day) had inspired the fictional environment for Cao Xueqin's complex tale of family life and intrigue.[23] Not long after, another commentator presented a more circular argument, suggesting that, as Cao Xueqin's novel enjoyed considerable popular currency in Prince Gong's day, it was quite possible that the book had provided the basis for the prince's garden designs.[24] [GRB] Notes:[1] This essay is a revised version of a chapter in The Great Wall of China, Claire Roberts and Geremie R. Barmé, eds, Sydney: Powerhouse Museum, with The ANU China Heritage Project, 2006. My thanks to Claire Roberts for encouraging me to explore this topic, to Sang Ye for his information on the secret history of Prince Gong's Palace in the early years of the People's Republic, and to Jeremy Clarke and John Minford for suggesting key sources. [2] See K.S. Chen and George N. Kates, 'Prince Kung's palace and Its Adjoining Garden in Peking', Monumenta Serica, 1940:5, p.60. In the late 1930s, Prince Puru, Prince Gong's son, told the authors of this whimsical usage in the family (ibid). [3] For details and a list of the city's princely mansions, see Wang Zi, Wangfu (Princely mansions), Beijing: Beijing Chubanshe, 2005. [4] It should be noted that Peking University and Tsinghua University are the official English names of those leading educational institutions. [5] Zhao Xun, 'Gong wangfu ji huayuan', in Jingcheng Shichahai (Shichahai, Beijing), Beijing: Zhongguo Wenshi Chubanshe, 2001, p.71. [6] It should be noted out that the Hall of Serene Longevity itself was a copy of the Chunhua Xuan at the Garden of Perfect Brightness; see Qianlong's remarks appended to one of his poems as recorded in Guochao gongshi xubian, juan, 59, 8b, referred to in Chen and Kates, 'Prince Kung's Palace', p.33, n.100. [7] Qing Renzong shilu, juan 37, quoted in Guan Wenfa, Jiaqing di (Emperor Jiaqing), Changchun: Jilin Wenshi Chubanshe, 1993, p.69. [8] See Chen and Kates, 'Prince Kung's Palace', pp.32–33. The name of the main hall in the courtyard was, however, changed to the Hall of Felicitous Propriety (Qingyi Tang) under Prince Gong who would often spend summer days there writing, and later to the Study of Promotion Conferred (Xijin Chai) by his son Prince Puwei. [9] The palace was allocated to the newly elevated Prince Gong in the fourth month of the second year of the Xianfeng reign. See 'Gaozong zhuzi zhuan', Qing shi gao, juan 221, Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1998, vol.3, p.2350. [10] Chen and Kates quote Prince Gong's remarks that 'in the period of Tongzhi the garden to the city residence was completed.' Furthermore, Dong Xun, a friend of the prince, visited the garden in 1873, at which time he noted that it was 'not long since completed'; see 'Prince Kung's Palace', pp.43, 62–63. [11] For details, see my 'The Garden of Perfect Brightness, a life in ruins', East Asian History, no 11, June 1996, pp.111–58, reprinted in China Heritage Quarterly, No. 8 (December 2006). [12] For details of Prince Gong's rise to influence and the period of restoration, see Mary C. Wright, The last stand of Chinese conservatism: the T'ung-Chih restoration, 1862–1974, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1957. [13] Since the rise of popular interest in Prince Gong's life and role in late-dynastic Chinese politics in recent years, details of his opposition to the rebuilding have become well known. See, for example, Tang Li and Yu Zukun, Gong qinwang Yixin zhenghai chenfu lu (An account of the political tempests of Yixin, Prince Gong), Wuhan: Hubei Renmin Chubanshe, 2006, p.132ff. [14] These translations are taken from Chen and Kates, 'Prince Kung's Palace', p.45. These authors provide a detailed description of the garden as it appeared in the late 1930s. During the 2006-2008 'restoration' of the mansion, this article was used extensively in the imaginative reconstruction of the mansion. [15] Ibid, p.44. [16] See Bruce Doar, 'The Elm Tree Palisades: The Great Wall of the Northern Song', in Features, China Heritage Quarterly, No. 6 (June 2006). [17] See Tie Yuqin and Wang Peihuan, Qingdi dong xun (Progresses to the east of the Qing emperors), Shenyang: Liaoning daxue chubanshe, 1991, for details of these trips. The last imperial visit to the ancestral graves beyond the Great Walls was undertaken by the Daoguang Emperor in 1829. [18] In one final act of imperial pretension, Prince Gong's tomb had been surreptitiously designed to include a subterranean marble mausoleum, something regarded as being above even his exalted station. [19] See Chen and Kates, 'Prince Kung's Palace', p.63, and Sun Banghua, Hui you beile fu—Furen daxue (Meeting at the prince's mansion: Fu-Jen Catholic University), Shijiazhuang: Hebei Jiaoyu Chubanshe, 2004, pp.194–95, 205. [20] The Soviet experts were sent from the KGB, the Interior Ministry and the General Commissariat for the police in Moscow. This material is based on the memoirs of Wang Zhongfang, secretary to the office in charge of the Soviet experts at Prince Gong's garden, latterly head of China's Legal Society, and Zhao Ming, deputy head of the translation section of the political department at the garden. [21] Shui Tianzhong and Li Xianting were notably active in this regard. The art magazine Zhongguo meishu bao, which they founded, played a key role in the '85 Art Movement. [22] See John Minford, 'The Dark Lane' in this issue. [23] Zhou Ruchang, Gongwangfu kao: Honglou meng Beijing sucai tantao (Researches on Prince Gong's mansion: a discussion of materials related to Story of the Stone in Beijing), Shanghai Guji Chubanshe, Shanghai, 1980. Zhou continued working on this hypothesis and presented a further detailed argument in his Honglou fang zhen (Daguanyuan zai Gong wangfu) (Searching for the real in the Red Chamber: Prince Gong's Mansion is Prospect Garden), Beijing: Huayi Chubanshe, 1998. The latter book also contains a Chinese version of Minford's preface (see pp.262-66), although what is lost in translation is the fact that John Minford was English, not Australian. [24] Lü Yingfang, 'Diyuan jinghua Gong wangfu', in Lin Keguang, Wang Daocheng and Kong Xiangji (eds), Jindai Jinghua shiji (Traces of history in modern Beijing), Beijing: Zhongguo Renmin Daxue Chubanshe, 1985, pp.90–91. |