|

FEATURES

Sapajou's Shanghai | China Heritage Quarterly

Sapajou’s Shanghai

Richard Rigby

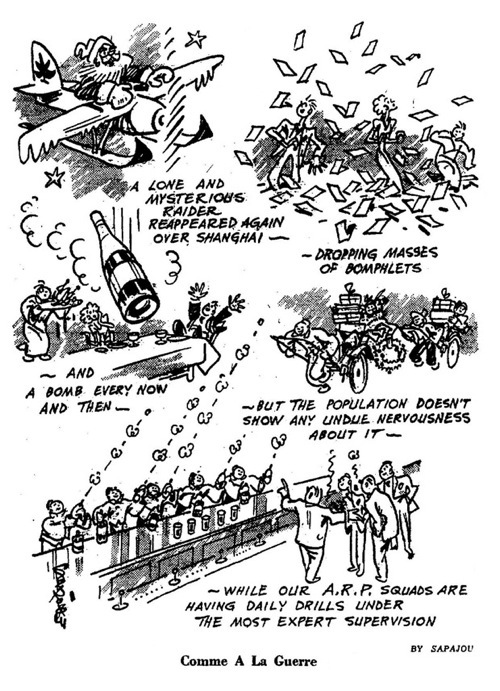

Fig.1 ‘Comme à la Guerre’. Source: North-China Daily News (hereafter NCDN), 22 December 1939.

Sapajou was the artistic nom de plume of Georgii Avksent'ievich Sapojnikoff, one-time Lieutenant of the Russian Imperial Army.[1] He was a graduate of the Aleksandrovskoe Military School in Moscow, and saw action in World War I, in which he was gravely wounded. As a result of his wounds, which left him with a pronounced limp for the rest of his life, he was invalided out of the army, and it was at this time that he began to take an interest in the visual arts, enrolling in evening classes at the Academy of Arts. The year 1920 found him, like so many of his compatriots, a refugee in Shanghai.

From 1925 onwards, Sapajou was on the staff of the North-China Daily News, probably the most important and prestigious English language newspaper in the Far East, and one that was rightly considered the mouthpiece of the largely British establishment of the International Settlement in Shanghai. Through his daily cartoons published over an almost unbroken period of some fifteen years, Sapajou became well known not only in Shanghai but also internationally. The publishing house of Kelly & Walsh produced several albums of his sketches of Shanghai life, and his illustrations appeared in a number of contemporary books on Chinese subjects.[2] He was also a Director and shareholder of the Shanghai Russian publishing house and newspaper Slovo.

Sapajou had the relatively rare distinction for a White Russian of being a member of the exclusive Shanghai Club (famed for its long bar-allegedly the longest in the world-which features in many of his cartoons of Shanghai life, e.g. Fig.1), and also of the Cercle Sportif Français (Fig.2, long known post-1949 as the International Club, and in more recent years, having been purchased and enlarged by the Okura hotel group, as the Huayuan 花園 or Garden Hotel, once more a gathering place of the fashionable). He was tall, bespectacled, and distinguished in appearance (a Russian lady of my acquaintance who knew him at the height of his popularity recalled that ‘all the girls loved him’), and walked with a cane as a result of his war wound. He appears in a number of his own cartoons, an example of which is given as Figure 3.

Following the entry of the Japanese into World War II and their occupation of the International Concession, the North-China Daily News was closed down and Sapajou had to seek work elsewhere. For a professional cartoonist and stateless person—hence not subject to the internment that was the lot of most of his colleagues who had been unable to escape the Japanese—the choices were few, and in order not to starve he joined the local German newspaper, which was of course controlled by Nazis. After the war was over and his former colleagues returned from other theatres or were released from internment, while many were sympathetic to his predicament, the times and situation were such that it was not possible for him to be reinstated in his former job. He spent the next few years in the north Shanghai suburb of Honkew (Hongkou 虹口), and eventually, shortly before the Communist takeover, was evacuated by UNWRA, with many other White Russians, now refugees twice over, to a displaced persons camp on the island of Tubabao in the Philippines. Already seriously ill, he died not long after arrival.

Such a sad ending to a life lived through turbulent times cannot, alas, be seen in any way as atypical for a man of Sapajou's background and period. What does mark him out from the crowd is the remarkable body of work he left behind, a fascinating, indeed brilliant, record of a vanished world, which taken in toto is a still insufficiently appreciated resource for students and scholars alike, and which can also provide great enjoyment to any with an interest in China in general or Shanghai in particular-especially at a time when in many ways that great city is drawing on its native and exotic genius to recreate itself after half a century of denial.

Fig.2 ‘Opening the Cercle Sportif—Anticipation and Reality’. Source: NCDN, 1 February 1926.

Fig.3 ‘The Girl He Left Behind. Sapajou Goes on Home Leave’. Source: NCDN, 27 October 1928. (The sad irony of the exile's life being that ‘Home’ was not home at all).

Fig.4 ‘Dulce Est Dissipere in Loco’. Source: NCDN, 26 July 1924. (The sun-helmeted diplomat, probably on leave at Beidaihe, is very sensibly reading Juliet Bredon’s unsurpassed Peking, first published by Kelly & Walsh, Shanghai, 1919.)

The cartoons themselves can be approached in a number of ways: taken sequentially, they provide a graphic chronological account of all the major developments in China from the warlord era through the Northern Expedition, the suppression of the Communists in 1927 and their subsequent re-emergence in rural guise, the vicissitudes and successes of the Nationalist Government, and the gradual rise of Japan as the major threat to both Chinese, and eventually Western, interests in China. Thematically, one can observe social change, within and between both the Chinese and foreign communities; the problems of extraterritoriality (‘extrality’ to the true Shanghailanders); the life of the various expatriate communities; anti-crime campaigns; Chiang Kai-shek's 蔣介石 New Life Movement; China at war, against foreigners and against itself; and also the way in which the accepted (by the North-China Daily News and its readers) views of certain figures or developments changed—e.g., Chiang Kai-shek himself, from red devil pitted against ‘good old’ Marshall Wu Pei-fu 吳佩孚 and other Treaty Port favourites, to ‘jolly good chap’ himself after 12 April 1927; or the Japanese, from ‘plucky little fellows’ doing a hard and at times nasty job that somebody probably had to do, to cruel aggressors (a change of view that, at least in retrospect, took a surprisingly long time). Over the years Sapajou also amassed a rich portfolio of portraits of historical figures, and perhaps even more interestingly, of ordinary people drawn from life, and typical characters drawn from an imagination fed by rich experience and an observant eye.

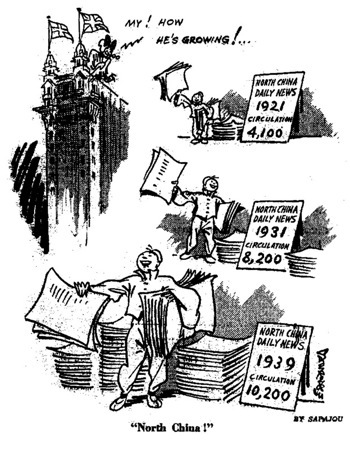

The fact that most of Sapajou's work was produced for the North-China Daily News, as already hinted at in the previous paragraph, naturally influenced the way issues were treated, and a few words about the newspaper are necessary before moving to the cartoons themselves. The newspaper commenced publication on 1 July 1864, and finally shut down its presses on 31 March 1951, the longest run enjoyed by any foreign language newspaper in China.[3] Its circulation for most of the period of Sapajou's association with it was around 7,000, largely amongst business and professional circles, amongst whom it had considerable influence. It would not be an exaggeration to claim that it sought for itself amongst the elite of the Shanghai International Concession, and indeed more broadly within the British community in China, an influence analogous to that of The Times at ‘Home.’

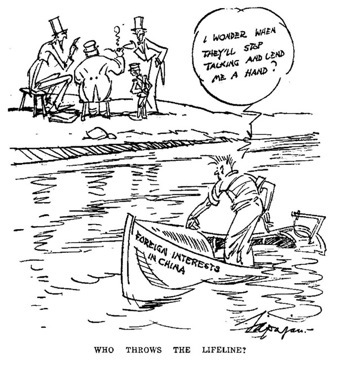

Fig.5 ‘Who Throws the Lifeline?’ Source: NCDN, 6 August 1925.

While popular with its readership, however, it frequently found itself—or rather placed itself—in difficulties with the Chinese authorities, whoever they might happen to be. This was hardly surprising, given its role as mouthpiece of what Arthur Ransome called, in a highly critical but perceptive (and at the time notorious) article, ‘The Shanghai Mind’.[4] The gist of his argument was that ‘nothing could be further from the truth than to imagine that the Englishmen in Shanghai represent an English outpost or share the English point of view. The Shanghailanders hold that loyalty begins at home, and that their primary allegiance is to Shanghai.’ They make difficult any good understanding between England and China because just as we at home are apt to think of them as English, so the Chinese, in China, make the same mistake. English policy and thought are

judged by the Chinese from the newspapers published in English in places like Shanghai and Tientsin. The Chinese naturally turn to these papers and judge England and England's policy by what they find there. It is impossible to persuade them that what they find is an expression not of the British but of the Shanghai mind. [In 1927] No Chinese, reading the Shanghai newspapers, could have had any other impression than that...England was fundamentally and irrevocably hostile to the only movement in China which had as its object the freeing of the country from the wholly unscrupulous warlords who secure Shanghai's approval by suppressing labour and the resentment of the whole country by the wholesale robbery which is making its normal development impossible.

A number of Sapajou's cartoons critical of the diplomatic corps in Peking (and later Nanking), and of home governments, typify this ‘Shanghai mind’ as described by Ransome.[Figs 4&5]

The attitude taken by the newspaper to Chinese political developments has been well described by a contemporary as ‘austere, and on occasion supercilious’,[5] but at times, particularly in the mid-to-late 1920s, it took a more openly hostile approach to the nationalist movements of the day. In 1929, the North-China Daily News was subjected to a postal ban by the National Government in Nanking, largely as a result of articles by its Peking correspondent, Rodney Gilbert,[6] and the news editor George E. Sokolsky.[7] In 1930, the editorial standpoint changed noticeably with the appointment of Edwin Haward as editor. Knee-jerk criticism of anything done by the National Government ceased, and a generally more objective approach became the norm. While not underrating the importance of Haward’s role, though, the change also reflected a broader modification of the position taken by many foreigners resident in China, who were gradually coming to see that they could live and work with the Nationalists, and that the alternatives—the Communists, banditry or, later, the Japanese—were all far more inimical to their interests. This is not to say that the change was universally welcome amongst the North-China Daily News’ readership; while subscriptions by well-educated Chinese rose, criticism from the more diehard foreign readers was at times severe.[Figs 6&7]

Fig.6 ‘As Others See Us’. Source: NCDN, 1 September 1937.

While there is no reason to believe that Sapajou did not share the general views of his peers, there can also be little doubt that he welcomed the later, more accommodating approach adopted by Haward. Honoured as he was by the way in which he had been accepted by the International Settlement elite, he always remained very actively involved in White Russian community affairs, which of itself could not but have given him a more sympathetic understanding of the underdog, as the position of many of his compatriots was dire indeed. More than this, though, is the obvious liking and understanding of the Chinese, indeed admiration for them—albeit not unmingled with exasperation, and on occasion horror—that comes through in his drawings. And for every cartoon that pokes fun at the Chinese (and leaving aside questions of political viewpoint, I have not found one that could be described as malicious) there are at least half a dozen that attack foreign foibles. At the same time, at least for the historian, it is precisely the relatively typical nature of Sapajou's views, and of the world that he portrays, that gives his work its particular value.

While it is inevitably the content of Sapajou's cartoons that provides the greatest interest to historians, he would never have enjoyed the influence and popularity that were his at the height of his career were it not for the high level of his artistic accomplishment. His keen eye and sharp powers of observation, together with the capacity shared with the best cartoonists of drawing together a host of specific characteristics, be they national, individual, of a time or of a place, to produce immediately recognisable and lasting types, was more than matched by the fluidity and subtle power of his lines—which over time became both simpler and stronger—and the accuracy of his profiling and shapes. He was also an accomplished water colourist, and Hua Junwu 華君武, the doyen of cartoonists in the People’s Republic of China (and who died in June 2010), recalled in a 1997 article being impressed as a young art student in 1930s Shanghai by an exhibition of these works.[8]

Fig.7 ‘ “North China!” ’ Source: NCDN, 12 January 1939.

Hua Junwu also acknowledged the influence that Sapajou's cartoons had exercised on him while studying at the Upper Middle School attached to the Shanghai Datong University 上海大同大學. The cartoons appearing regularly in the North-China Daily News fascinated him at a time when he himself had just begun to study drawing, and he frequently tried to imitate their style, even to the extent of adopting a similar signature (while Sapajou signed his pictures in English, he did so in Chinese style, vertically from top to bottom). What struck Hua most about the cartoons was the way in which they managed to completely bring out the inner aspect of their subjects, be they Englishmen, Japanese or Chinese, and he confessed in retrospect to embarrassment at the extent and quality of his imitations of the master. Hua was not alone in this admiration for Sapajou's work, whatever he or his contemporaries may sometimes have felt about the content. Cartooning in the modern sense was a new medium in China, the political potential of which was quickly felt.[9] The artists Huang Miaozi 黃苗子 and his wife Yu Feng 郁風 were also struck by Sapajou's cartoons,[10] and although I have been unable to trace any direct acknowledgment, there are striking similarities between some of Sapajou's characters and those appearing in Zhang Leping's 張樂平 famous San Mao 三毛 series, which first started to appear in Shanghai in 1935.[11] Hence the view—no more than just—of a modern Shanghai scholar, writing in a popular newspaper in 1997, that ‘while old Shanghai was indeed ‘an adventurer's paradise’, there were some foreign artists, such as Sapajou, who made contributions to culture.’ [12]

Now to the actual cartoons. I have arranged them in seven sections, with only such notes as are necessary to explain what may not be immediately apparent from the drawings themselves, to place them in context or to draw out their worth as a scholarly resource.

Warlords

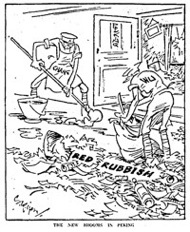

Fig.8 ‘The New Brooms in Peking’. Source: NCDN, 21 April 1926.

Fig.9 ‘An Answer Which Needs a Special Character’. Source: NCDN, 31 January 1939.

Fig.10 ‘The Flirtatious Feng—The Soviet is hopefully looking towards re-establishment in China under an agreement with General Feng, but is finding the latter elusive and more flirtatious than helpful’. Source: NCDN, 4 August 1928.

Warlords were judged primarily by the degree to which they were regarded as friendly or hostile to foreign (that is, Shanghai) interests. Wu Peifu was the favourite of the British. He was well disposed, had at least some of the attributes of the traditional Chinese gentleman with whom the British felt an instinctive affinity, and brooked no nonsense from Communists or organised labour.[Fig.8] Long after he had ceased to be a serious contender for national leadership, he was still respected (not only by the British) for his integrity in refusing to yield to Japanese blandishments to serve as a puppet.[Fig. 9] No other warlord appears in so consistently positive a light in Sapajou's cartoons, and those such as Feng Yuxiang 馮玉祥 who dared to challenge foreign interests were generally negatively portrayed—although where the latter is concerned one cartoon invites the viewer to enjoy a bit of Schadenfreude at the expense of the Soviets, who did not seem to be getting a very good return for their investment in ‘the Christian Warlord’.[Fig.10]

Fig.11 ‘“ Ctte Guerre Chinoise, Plus Rigolo Que Verdun, ’Pas?” — Among the French Marines at Lokawei’. Source: NCDN, 6 September 1924.

Fig.12 ‘Some of the Russian Soldiers and a Portion of the Armoured Train; Sketched at Shanghai North Station by Sapajou’. Source: NCDN, 30 January 1925. (The accompanying article observed: ‘It was noticeable that these men punctiliously saluted their Chinese officers’.)

Fig.13 ‘Not a Success at Present’. Source: NCDN, 5 May 1930.

At times warlord conflicts could impinge directly on the security of Shanghai, such as during the Jiangsu-Zhejiang conflict of 1924, and the forces at the disposal of the French and International Settlements had to be mobilised, but generally the fighting was not taken particularly seriously.[Fig.11] Occasionally foreign interest could be heightened by the presence of White Russian troops amongst the Chinese forces operating in the vicinity of Shanghai, for example those who arrived at the Shanghai North Station on 28 January 1925, as part of Zhang Zuolin's 張作霖 Fengtian vanguard,[Fig.12] or the Russian regiments of the dreadful—but anti-Red—Zhang Zongchang 張宗昌.[13]

Fig.14 ‘The Horrors of War’. Source: NCDN, 15 August 1930.

Fig.15 ‘The Patient Star Gazer’. Source: NCDN, 15 November 1924.

Fig.16 ‘Sapajou’s Observations on the Liuho Front: Dull work—with other fellows at dinner too!; Such pretty country to spoil; Always merry and bright—a typical Chekiang soldier’. Source: NCDN, 10 September 1924.

The not wholly discreditable preference of many Chinese generals to settle their differences through threatening telegrams and bombastic manifestos rather than through serious fighting was predictably made the object of Sapajou's wit.[Figs 13&14] Equally apparent, though, is the sheer confusion of this troubled age, at times reflected with exasperation, but at others with ‘oriental’ detachment.[Fig.15] Politics apart, Sapajou's many drawings of ordinary Chinese soldiers, taken from life in the course of his frequent visits to the lines, display a very real sympathy for them at the human level, as well as providing us with marvellous vignettes of the military life that was sadly all too much a feature of the China that Sapajou knew so well.[Figs 16&17]

The Northern Expedition

Fig.17 ‘Field Kitchen at Nansiang’. Source: NCDN, 13 September 1924.

Fig.18 ‘The Chinese William Tell’. Source: NCDN, 24 December 1925.

Fig.19 ‘When the Birds Go North Again—A flight of Red Kuomintang, despairing of the efficacy of Bolshevism in Canton, has set in to Peking’. Source: NCDN, 31 July 1925.

The Northern Expedition, marked by the alliance between Nationalists and Communists, was the most dramatic reflection of the revolutionary and national consciousness which followed and grew out of the May 30 Movement (1925)[14] and the great Canton-Hongkong strike. As such, it was regarded with great hostility by those who saw it as a direct threat both to foreign trade, Shanghai's very raison d’être, and their own position and privileges, symbolised by extraterritoriality and underwritten by the Unequal Treaties—although they, or at least the North-China Daily News, were not so crass as to put it quite like this, preferring instead to identify their interests with those of the ‘real’ China.[Fig.18]

Fig.20 ‘Gen. Chiang Kai-shek—“The landing doesn’t look particularly attractive on those nasty spiky things” ’. Source: NCDN, 26 August 1926.

Fig.21 ‘The Hankow Bank Employee’s Visions of Fair Fortune’. Source: NCDN, 12 February 1927.

Fig.22 ‘Sapajou Makes the Round of the Boundaries’. Source: NCDN, 16 March 1927.

While initially the Kuomintang, or more specifically the Kuomintang left, was regarded with some scorn,[Fig.19] once the military expedition got under way the tone of commentary, and cartooning, became more serious, although at first considerable hope was placed in the capacity of the more reliable warlords, such as Wu Peifu, to put a stop to it.[Fig.20] The taking of the British concession at Hankow in early 1927 came as a great shock, a shock that was further intensified for the North-China Daily News readership when Sir Austen Chamberlain told Parliament that Britain would not attempt to take it back. Sapajou caught the mood with ‘father’ John Bull reproving his ‘son’ Sir Austen, sheepish and in short trousers, with the words ‘and how could you say such a thing, sonny?’[15] Just as alarming, however, were the demands being raised against foreign employers by the new authorities, which included militant unions—including that of the Hankow bank employees.[Fig.21] As the revolutionary forces approached Shanghai, therefore, the foreign community prepared for the worst, and the Shanghai Volunteer Corps, boosted by the auxiliaries of Britain's far-flung Empire, dug in for the siege.[Fig.22]

Fig.23 ‘Who Will Ride Him?—In the struggle for mastery of the Kuomintang steed, General Chiang Kai-shek seems to have been unseated by the Communists’. Source: NCDN, 17 March 1927.

Fig.24 ‘The Powers—“This hybrid code they use in China nowadays is very difficult to follow” ’. Source: NCDN, 26 March 1927. (On 25 March Sokolsky had an article arguing that the time had come for a showdown between the CCP and the Chiang Nationalists, following the fall of Nanking. He noted how Chiang had kept well clear of Hankow.)

Fig.25 ‘Cat and Mouse in Chapei—General Chiang Kai-shek is reported to be taking strong measures against the Communist braves’. Source: NCDN, 6 April 1927.

While preparations were made to meet the worst, however, readers of the North-China Daily News were aware that the revolutionary forces were by no means fully united, and that there were possibly grounds for hope as well as for concern. As his portrayal in Figure ** indicates, in the early stages of the Northern Expedition Chiang Kai-shek was seen as very much part of the problem. As late as September 1926, in a cartoon entitled ‘The obsession of General Chiang Kai-shek,’[16] he is shown waving a pair of revolvers, a hysterical expression on his face, attempting vainly to rid the Yangtze in the vicinity of Hankow of foreign gunboats. By early March 1927, though, he is shown in struggle with the Communists (represented by Borodin), but it is the latter that appear to be winning.[Fig.23] This was all very confusing for the waiting and apprehensive foreigners, as a further cartoon published only a week later makes very clear.[Fig.24] Two weeks after that, however, with Chiang having taken up arms against his former Communist allies, the situation appeared very different indeed,[Fig.25] and by July, with the Communists apparently defeated and Moscow's plans in disarray, it was possible for Sapajou to show Chiang for the first—but by no means the last—time in an unquestionably benign, indeed heroic, light.[Fig.26] All in all, a pretty good result for the readers of the North-China Daily News, and for China's trade and British mercantile interests: the two, naturally enough, being seen by the readership as essentially one and the same thing.[Fig.27]

The Nanjing Decade

Fig.26 ‘The Broken Melody—Accompanist: Has he forgotten the tune?’ Source: NCDN, 5 July 1927. (The Russian pianist is Karakhan, Soviet envoy in Peking who in May 1924 had concluded the Sino-Soviet treaty.)

Fig.27 ‘The Guest:—“Now as you are convalescing, you ought to be careful and not to read enervating books”’. Source: NCDN, 28 January 1928.

Fig.28 ‘Nanking’s Mode in Barbering’. Source: NCDN, 30 December 1929.

The cartoons in this folio can provide no more than a glimpse of China and its rulers in the period between the establishment of the National Government in 1928 and the outbreak of full-scale war with Japan in 1937, known as the Nanjing (Nanking) Decade. As noted above, the attitude taken to this government by the North-China Daily News was on the whole fairly objective, and indeed at times sympathetic. Once it was understood that Chiang Kai-shek and his government intended to safeguard foreign trade and the security of foreign interests in China, there was even a guarded acceptance that the foreigners would and should make some modest adjustments.[Fig.28] While the Northern Expedition and the establishment of the National Government had brought unity of a sort, it was constantly under challenge from within and without, and strive as it may, the National Government was never able to even approach the degree of centralised power that was its ideal. This continuing lack of unity was a theme in many of Sapajou's cartoons throughout this period (for instance, Figs 29&30), as was the financial strain imposed by the constant pressure of military expenditure required to deal with these threats.[Fig.31]

Fig.29 ‘Chinese Dialects’. Source: NCDN, 2 November 1931.

Fig.30 ‘Who Is Driving This Car?’ Source: NCDN, 8 December 1931.

Fig.31 ‘Something Wrong with the Horse’. Source: NCDN, 31 October 1933.

The essentially conservative readers would have derived a good deal of amusement from the way in which Sapajou and his editors dealt with such revolutionary pretensions as the new regime still maintained, expecting, for instance (and as history has shown, with considerable justification) that it would take more than new regulations to do away with the traditional cycle of the years and the Chinese New Year celebrations.[Fig.32] Similar scepticism, mixed with an element of regret where puritanical attacks on female beauty were concerned,[Fig.33] was expressed with regard to Chiang's New Life movement, although along with this scepticism went the wish that the movement might actually do something about real abuses[Figs 34&35]—together with the realisation (plus ça change!) that what might seem appropriate in the wealthier urban parts of the country was probably totally irrelevant elsewhere.[Figure 36] Lying behind these attitudes was the frustration felt by many observers who have come to know China well, by no means all unsympathetic, over the tendency to regard a problem having been solved once the necessary words have been uttered—or better, written.[Fig. 37]

Fig.32 ‘Old Custom Hard to Beat’. Source: NCDN, 7 February 1930.

Fig.33 ‘Difficult Times for Women’. Source: NCDN, 4 September 1934.

Fig.34 ‘A Tip for “New Life” Movers’. Source: NCDN, 28 April 1934.

Despite such criticism, however, Chiang Kai-shek himself continued to be held in a position of some esteem, notwithstanding his tendency to attempt to take personal charge of an impossibly large number of issues.[Fig.38] Foreign Shanghai joined wholeheartedly in the rejoicing following Chiang's release at the conclusion of the Xi’an (Sian 西安) Incident in December 1936,[Fig.39) and looked forward to the possibility of a newer and brighter future for China, if the necessary lessons were learned.[Fig.40] Alas, even had the will and ability been there, it is unlikely that the activities of the subjects of the following two portfolios would have permitted the realisation of this benign scenario.

Communists

Fig.35 ‘He Jumps First’. Source: NCDN, 3 April 1934.

Fig.36 ‘The New Life’. Source: NCDN, 23 October 1934.

Fig.37 ‘The Novelist Disturbed’. Source: NCDN, 4 August 1930.

Up to end of the Northern Expedition, Communists really meant Soviet Russians—Borodin and Kharakan, together with a villainous looking Bolshevik soldier, make the most frequent appearances, all three alternately filling the heads of credulous Chinese students with their poisonous doctrines, or seeking to seduce a China portrayed by Sapajou as an attractive but impressionable and at times dangerously innocent young woman.[Figs 41-43] Following the collapse of the first period of Communist-Kuomintang cooperation, Chiang Kai-shek's action in Shanghai of 12 April 1927 and other heavy blows launched against the Communist party, the greatest danger seemed to have passed, although the continuing presence of Chinese students in Moscow—including Chiang's son Chiang Ching-kuo (Jiang Jingguo)—was noted.[Fig.44] By August 1929, with tough action against remaining Communists in Shanghai by the authorities of the French Concession, International Settlement and the Chinese city, the problem seemed, if not fully settled, at least on the way to a solution—as is demonstrated in a somewhat complacent cartoon showing the three police forces hauling in a very full net of Communist fish.[Fig. 45]

Fig.38 ‘Mass Resignation—First Wang Ching-wei Then Entire Cabinet’. Source: NCDN, 12 August 1932.

Fig.39 ‘Released Captive’. Source: NCDN, 27 December 1936.

Fig.40 ‘The Lesson Of Sian’. Source: NCDN, 5 January 1937.

Perhaps more prophetically than Sapajou had intended, however, a few fish that have escaped capture are swimming fast in the opposite direction, Thus it was that one year later, far from having disappeared completely, the Communists—from now on portrayed just as Sapajou was wont to draw more traditional Chinese bandits, give or take a hammer and sickle here and there—were shown as capable of seriously threatening foreign interests on the Yangtze,[Fig.46] From that time on, Chiang Kai-shek's various encirclement and other anti-Communist campaigns periodically provided Sapajou with subjects. Needless to say, the sympathies of the artist and his editors were entirely with Chiang, but this did not stop them from noting either his financial difficulties in prosecuting his campaigns,[Fig.47] nor the fact that despite his best efforts, the enemy, far from being defeated, seemed to be multiplying.[Fig.48]

Fig.41 ‘Swollen With Wind and the Rank Mist They Draw, Rot Inwardly and Foul Contagion Spread’. Source: NCDN, 6 June 1925.

Fig.42 ‘In the Valley of the Shadow’. Source: NCDN, 10 August 1925.

Fig.43 ‘Which Physician?—The better bedside manner seems to stand a very good chance’. Source: NCDN, 10 August 1925.

We have already seen two of Sapajou's cartoons dealing with the Xian Incident, but another is included here which warns of the dangers of any alliance with the Communists, pointing to the tragic contemporary example of Spain.[Fig.49] Sapajou's final comment on this question came one month later, and while the sentiments expressed—the need for the Communists to abandon their doctrines and methods before joining forces with ‘Miss China’, busy watering her pot of Three People's Principles—would have been fully approved by the Guomindang, the wolves which the Communist guerilla has in tow do not bode well either for the Principles or for the young lady.[Fig.50]

Japan

Fig.44 ‘The Moscow Teacher:—‘And what do you think of your father, Chiang Kai-shek, the traitor?’ Source: NCDN, 26 April 1927. (Chiang Kai-shek's son, as school in Moscow, is said to [have] published an article denouncing his father's anti-Communist campaign).

Fig.45 ‘Gathering in the Net’. Source: NCDN, 1 August 1929.

Fig.46 ‘The Red Watch on the Yangtze’. Source: NCDN, 9 August 1930.

While it would be a mistake to describe Sapajou or the North-China Daily News as ever having been pro-Japanese, neither could it have been described as anti-Japanese, any more than was general Treaty Port sentiment towards Japan. Japan had been widely admired for the success of its modernisation efforts since the Meiji Restoration, it had been joined in formal alliance relationship with Britain before and during World War I, and it had actively participated in the anti-Soviet allied intervention following the Bolshevik revolution (as it had in the suppression of the Boxers in China by the Eight Allied Armies at the turn of the century). In Shanghai, Japanese industry was of considerable significance. There was a large Japanese community, represented on the Board of the International Settlement and the Rate Payers' Association. It is fair to say that for well into the 1920s, there was at least grudging, and sometimes more than grudging, admiration for Japan's efforts in maintaining order, if not law, in the chaotic conditions of China at the time,[Fig.51] and for its tough line on the ‘Unequal Treaties’.[Fig.52]

Fig.47 ‘Lubrication Needed’. Source: NCDN, 13 October 1933.

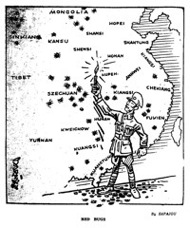

Fig.48 ‘Red Bugs’. Source: NCDN, 1 December 1934.

Fig.49 ‘ ‘Don't Do It, Sister!’ ’ Source: NCDN, 24 January 1937.

The divergence between Japanese and Western interests in China started to become more clear as Japan strengthened its position in the North East, particularly following the establishment of Manchukuo.[Fig.53] From the treatment of the Sino-Japanese hostilities in Shanghai in 1932, one can see the beginnings of a more sympathetic attitude towards China, reflecting in part at least the surprisingly (to both the Japanese and other foreigners) brave and stubborn resistance put up by the Chinese.[Fig.54] Overall, however, the fighting was seen more as a nuisance than a real threat, or as a matter in which the interests of the foreign community were clearly engaged on one side or the other.[Fig.55] As the decade advanced, the lines gradually became more clearly drawn and the danger posed by Japan to the maintenance of the order that had served ‘Shanghai’ interests so well became increasingly obvious.[Fig.56]

Fig.50 ‘Exotic Paraphernalia—Miss China:—“You may come back but leave those things behind!” ’ Source: NCDN, 24 February 1937.

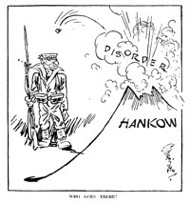

Fig.51 ‘Who Goes There?’ Source: NCDN, 24 September 1927. (Rioting in Hankow: on 20 September some Chinese soldiers attempted to rescue a fellow Chinese [Communist] who had been arrested from a Japanese ship. Clashes between Chinese and Japanese resulted.)

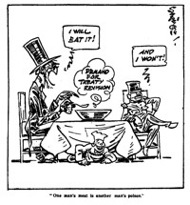

Fig.52 ‘One Man’s Meat Is Another Man’s Poison’. Source: NCDN, 28 July 1928 (in reference to Kelly's reply to C. T. Wang's demands for treaty revision—the ‘prose poem’ [story front page 28/7/28]).

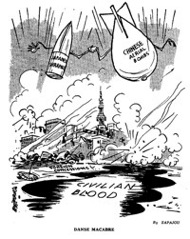

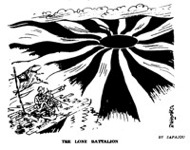

Between the recommencement of hostilities in Shanghai in 1937 and the eventual takeover of the International Settlement by the Japanese, the fighting and its effect on Shanghai and China more widely were the subject of many of Sapajou's cartoons, including some of his most striking, of which space allows only a few in this small essay. The first deals with the tragic incident in which Chinese aircraft, attempting to attack the flagship of the Japanese fleet anchored the Huangpu, the Idzumo, instead succeeded on three separate occasions in dropping their bombs on the streets of Shanghai, most notoriously on Nanking Road, not far from the Cathay Hotel (now the Peace Hotel), with great loss of life.[Fig.57] The second portrays in a particularly powerful image the heroic resistance put up against overwhelming odds by the Chinese soldiers who became known in English as ‘The Lone Battalion,’ and to the Chinese of the time as ‘The Eight Hundred Heroes’.[17][Fig.58]

Fig.53 ‘No Admission’. Source: NCDN, 15 October 1931.

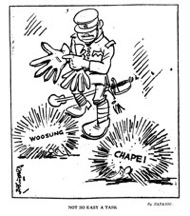

Fig.54 ‘Not So Easy a Task’. Source: NCDN, 11 February 1932.

Fig.55 ‘Tennis à la Mode’. Source: NCDN, 22 February 1932.

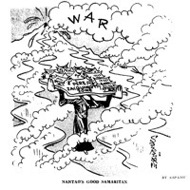

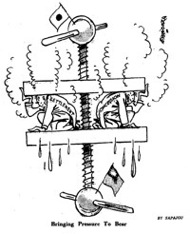

While Western Governments would not become directly involved in the conflict for some years, many sympathetic individuals and non-Government organisations did what they could for the growing numbers of Chinese civilian victims of the hostilities, one aspect of which is reflected in Sapajou's portrayal of the non-combatant safe zone which a French priest, Father Jaquinot, managed to negotiate with the Chinese and Japanese authorities: managed with considerably less than total success, nevertheless saving lives that would otherwise have been lost.[Fig.59] As the conflict broadened, Shanghai was not the only part of China where Western, particularly British, interests were threatened, as is graphically demonstrated in Sapajou's cartoon of Hongkong about to be engulfed by a tidal wave.[Fig.60] While sympathies were largely on the side of the Chinese by the late 1930s, however, foreign Shanghai could still see itself as the victim of pressures from both the warring parties, as is shown by a cartoon published in May 1939, at which time the wish that the ratepayers of the International Settlement could simply be left alone to get on with the serious business of making money was as strong as ever.[Fig.61] That this was not to be, however, and that the Shanghai of the Shanghailanders was coming to an end, was presaged only a fortnight later in another cartoon which showed perhaps greater foresight than either the artist or the Japanese gentleman portrayed realised.[Fig.62]

Australia

Fig.56 ‘Double Suicide?’ Source: NCDN, 28 July 1937.

Fig.57 ‘Danse Macabre’. Source: NCDN, 16 August 1937.

Fig.58 ‘The Lone Battalion’. Source: NCDN, 30 October 1937.

Australia and Australians have had a long association with Shanghai—as journalists, officials, servicemen and women, and in business. Throughout the period in which Sapajou worked, however, they tended to be subsumed under a more general British and Imperial identity. The following exchange recorded by George E. Morrison in his An Australian in China tells a tale little understood by many Australians today:

We drew alongside the junk and an Englishman appeared at the window.

‘Where from?’ he asked laconically.

‘Australia.’

‘The devil, so am I. What part?’[18]

It should be added that the Australian Englishman, Morrison, was proud to identify himself as a Scot.

Fig.59 ‘Nantao’s Good Samaritan’. Source: NCDN, 18 November 1937.

Fig.60 ‘The Tidal Wave’. Source: NCDN, 31 May 1938.

Fig.61 ‘Bringing Pressure to Bear’. Source: NCDN, 4 May 1939.

Nevertheless, Australia as Australia also left its mark, and the annual Anzac Day service at the War Memorial on the Bund (destroyed by the Japanese) was a regular feature on the Shanghai calendar, as were certain other features of the country faithfully recorded by Sapajou in five of the six cartoons that I have been able to identify dealing with or mentioning Australia: gambling, specifically the introduction of ‘the Tote’ in Victoria;[Fig.63] trade unions;[Fig.64] test cricket, twice—the ‘bodyline’ controversy clearly attracting far more attention from discerning Shanghailanders than problems closer to home;[Figs 65&66] and trade, where the staple and now stereotypical pre-war exports to China of primary produce are counted as little by Sapajou against the equally stereotypical kangaroo, cricket, boomerang and Sydney Harbour Bridge.[Fig.67] The last cartoon in which Australia features introduces a more sombre note, and links us back to the previous folio by showing Australia as the ultimate objective of Imperial Japanese pearl diving in the South Seas.[Fig.68]

Shanghai

Fig.62 ‘…And Will the Top Stand?’ Source: NCDN, 18 May 1939.

Fig.63 ‘Melbourne Legalizes the “Tote” ’. Source: NCDN, 16 December 1927.

Fig.64 ‘The More We Are Together!’ Source: NCDN, 24 July 1928.

Despite the value and interest of his political commentary, Sapajou is perhaps at his very best, and most sympathetic, when he is dealing with the rich and multi-faceted life of the Shanghai in which he lived, and this did in fact provide the themes for the bulk of his work. Accordingly, we can but touch on a very few examples that may serve to bring out some of the most persistent themes and aspects of life as it was lived in the International Settlement—and ‘Frenchtown’—by Sapajou and his contemporaries. Some of these are as topical in today's Shanghai as they ever were: for instance, ridiculously high and overvalued rents in newly developed areas.[Fig.69] Shanghai's impossible traffic was another such theme, although the particular and perpetual conflict between rickshaw pullers and the Settlement's Sikh police, to which Sapajou returned on various occasions, is now, mercifully, no longer with us.[Figs 70&71] But the difficulties caused by the coexistence of two forms of vehicular traffic, powered respectively by man and by motor, are as real as ever. The weather was also a constant subject, especially the summer heat and the drama, but relief, of typhoons—the advance of which were carefully plotted by the Jesuits at their observatory and weather station in Zikawei (aka. Siccawei, Xujiahui).[Fig.72] Today, however, air-conditioning has largely rendered superfluous the annual exodus of wives and children during the hottest months, leaving the men to cope as best they might with the assistance of the Long Bar or such other consolations as Shanghai was generally able to provide.[Fig.73] The beauty of Shanghai's women, both foreign and local, was another regular—and timeless—theme of Sapajou's, and it was clearly at times difficult to decide between the two;[Fig.74] although where the world's sailors were concerned, the choice appears to have been unanimous.[Fig.75]

Fig.65 ‘The Real Issue’. Source: NCDN, 18 January 1933.

Fig.66 ‘P. C. John Bull:—Pass Along Please, No Interruption While Game Is in Progress!’ Source: NCDN, 28 February 1937.

Fig.67 ‘Not the Goods Wanted’. Source: NCDN, 31 January 1934.

This was of course but one aspect of Shanghai's cosmopolitan nature, celebrated by all true Shanghailanders, not least Sapajou, in many ways.[Figs 76-78] The Fourteenth of July, a major feature of expatriate life in Shanghai whether in the Settlement or Frenchtown, was always marked with a new cartoon,[eg. Fig.79] and the major Russian festivals of New Year and Easter were recorded, at times with a particular and understandable poignancy.[Fig.80] Nor were the quaint customs of other minority groups ignored.[Figs 81&82] The annual Christmas cartoons, however, never failed to bring out the fundamentally British core of the International Settlement,[Fig.83] shown no more clearly than by the scale of the celebrations mounted to mark the coronation of George VI in 1937.[Fig.84] It must also be added that as the decade of the Thirties proceeded in its increasingly lamentable fashion, the cosmopolitan harmony in which Shanghai rightfully took much pride came under increasing strain[Fig.85]

Fig.68 ‘Pearl Diving in South Seas’. Source: NCDN, 7 March 1939.

Fig.69 ‘Shanghai Style’. Source: NCDN, 2 April 1935.

Fig.70 ‘Traffic Problems As Seen from a Ricsha’. Source: NCDN, 25 October 1923.

Its cosmopolitan nature, though, was not the only basis of Shanghai's pride, as Sapajou also makes very clear. Surrounded by a frequently chaotic environment, the International Settlement had long provided at least relative peace and security, not least for those Chinese most opposed to much of what it stood for.[Fig.86] In the years following the Communist victory in 1949—at least until the dramatic re-emergence of Shanghai since the 1990s—it has become increasingly easy to regard it with either nostalgia or execration. What has so often been forgotten amongst the images of a lost world of louche living, art deco architecture and/or an exploited and starving Chinese underclass, is quite how modern it was—modern in every sense, culturally, economically, physically. It was new, powerful, energetic and vigorous, and for many who participated in its development, foreign or Chinese, exhilarating. Moreover, where the International Settlement was concerned, at least following the post-May 30 and Northern Expedition reforms and realignment with the National Government and the burgeoning Chinese bourgeoisie, it was a joint enterprise between Chinese and foreigners. This was a theme, of Shanghai as a unique city which would cede its place to no other, to which Sapajou returned time and again, and which in a sense informs and enlivens the whole body of his work. Three examples, from 1926, 1931 and 1937 close this portfolio.[Figs 87&89]

Envoi

Fig.71 ‘Only a Dream!’ Source: NCDN, 29 Ocotber 1923.

Fig.72 ‘Father Froc’s Parting Word’. Source: NCDN, 12 August 1931.

Fig.73 ‘Moscow Influence?’ Source: NCDN, 6 July 1937.

And yet Sapajou's world did indeed come to an end, and with it, his best years as a creative artist. While, as has been noted in the introduction, he continued to draw for the Shanghai German newspaper following the Japanese occupation of the Settlement, this was no longer the world in which he had come to occupy so notable a position, and which he had portrayed so well. Better to leave him, then, with one last and poignant drawing of late 1941, ‘The Golden Autumn’.[Fig.90] After the oppressive heat of summer and the typhoons that frequently mark its end, Shanghai's golden autumn—the Jin Qiu 金秋—never fails to provide a few precious weeks of relief, the more beautiful for its relative shortness before the chilling winter rains and sleet set in. But in October 1941, it was no longer possible to avail oneself of the traditional pleasures of the season. Winter was already on the way.

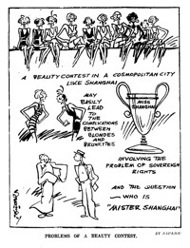

Fig.74 ‘Problems of a Beauty Contest’. Source: NCDN, 13 August 1931.

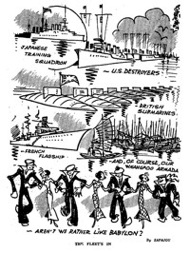

Fig.75 ‘The Fleet’s In’. Source: NCDN, 21 April 1936.

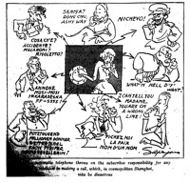

Fig.76 ‘The Automatic Telephone Throws on the Subscriber Responsibility for Any Mistakes in Making a Call, Which, in Cosmopolitan Shanghai, May Be Disastrous’. Source: NCDN, 7 April 1924.

Fig.77 ‘Where East Meets West’. Source: NCDN, 26 February 1925.

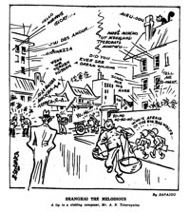

Fig.78 ‘Shanghai the Melodious—A tip to a visiting composer, Mr A. N. Tcherepnine’. Source: NCDN, 14 April 1934.

Fig.79 ‘Quatorze Juillet’. Source: NCDN, 14 July 1932.

Fig.80 ‘The Kremlin of Exile’. Source: NCDN, 24 April 1938.

Fig.81 ‘St. David’s Day: Cymdeithas Dewi Sant’. Source: NCDN, 1 March 1933.

Fig.82 ‘Who Said Shanghai is a Babel?’ Source: NCDN, 30 November 1933.

Fig.83 ‘Christmas Conceits’. Source: NCDN, 24 December 1934.

Fig.84 ‘Shanghai Goes the Whole Hog’. Source: NCDN, 13 May 1937.

Fig.85 ‘Let’s Not Discuss Politics’. Source: NCDN, 19 April 1929.

Fig.86 ‘The Military Tiger Is Abroad’. Source: NCDN, 9 September 1924.

Fig.87 ‘The Vision of a Future Ambition’. Source: NCDN, 10 May 1926.

Fig.88 ‘What Shanghai Thinks To-day Manchester May Think Tomorrow’. Source: NCDN, 26 January 1931.

Fig.89 ‘—And Many Happy Returns!’ Source: NCDN, 8 July 1937.

Fig.90 ‘The Golden Autumn’. Source: NCDN, 10 October 1941.

Notes:

* This article has been revised on the basis of the author’s ‘Sapajou’, which appeared in East Asian History, Issue 17/18 (June/December 1999).

[1] These biographical notes are based largely on the reminiscences of Mrs M.M. Colan (now deceased), several references in the highly lubricious but valuable account of pre-war Shanghai by Ralph Shaw, Sin City, London: Everest Books, 1973, A History of the Russian Residents of Shanghai (Shanghai e-qiao shi), ed. Wang Zicheng, Shanghai: Sanlian Shudian, 1993, and a few occasional references from the North-China Daily News itself.

[2] For example, Shanghai's Schemozzle (North-China Daily News, 1937), republished in Earnshaw Books, China Economic Review Publishing, 2007; Five Months of War: the hostilities between China and Japan in narrative and picture, North-China Daily News, 1938; Shanghai Album, German Information Bureau, Shanghai: Max Noessler & Co, 1943. For examples of illustrations in other books, see for example Carl Crow, 400 Million Customers: the friendly Chinese and his business, London: Hamish Hamilton, 1937; idem, The Chinese are like that, Cleveland, Ohio: World Publishing Company, 1943; D. de Martel and L. de Hoyer (trans. D. de Warzee), Silhouettes of Peking, Peking: China Booksellers, 1926; J.A. Rabbitt (Shamus A'Rabbit), China Coast Ballads, Shanghai: A.R. Hager, 1938; J.A. Rabbitt, Ballads of the East, Shanghai: A.R. Hager, 1937; but there are many more.

[3] Much of what follows is drawn from the notes accompanying the microfilm holdings of the North-China Daily News issued by the Center for Chinese Research Materials (Ping-Kuen Yu, Director) of the Association of Research Libraries, Washington DC.

[4] ‘The Shanghai Mind,’ originally published in the Manchester Guardian, was republished very shortly after in Ransome's The Chinese Puzzle, London & Boston: G. Allen & Unwin, 1927.

[5] John B. Powell, My twenty-five years in China, New York: Macmillan, 1945.

[6] Author of What's wrong with China?, London: John Murray, 1926. The book, which went through three print runs in its first year, was controversial, and its power to shock is if anything greater now than at the time of its writing. The fly-leaf of the copy held by the Feng Pingshan Library at Hong Kong University, originally from the Hankow Club, is inscribed ‘Nothing, you dog!’ Gilbert had been closely associated with Wu Pei-fu, and was highly critical of the movement to abolish the unequal treaties, about which he wrote another book in 1928. The year 1941, however, found him working with the Nationalists in the KMT Central Propaganda Department in Chongqing, united at last in the war against Japan.

[7] Sokolsky's position was more nuanced than that of Gilbert. A New York Jew of Polish extraction, he had been a fellow student of Hu Shi's at Columbia, and as well as his career as author and journalist occupied at different times a number of positions in Chinese organisations, including advisor to the chief of the Chihli police, advisor to the Shanghai Students Union (1919), and manager of the China Bureau of Public Information (1920). His wife was Chinese, and he claimed in the preface to his The Tinderbox of Asia, New York: Doubleday Doran, 1932, that ‘it is only because I love China that I am moved, at times, to chastise her leaders’—no more a unique position in his day or ours than that of the Chinese authorities in failing to see it that way.

[8] ‘Sabaqiao’ 萨巴乔 (Sapajou), Xinmin Wanbao (Shanghai), 24 June 1997. Hua's short piece in the popular ‘Yeguangbei’ 夜光杯 column picks up a reference to Sapajou in a contribution to the same column by the writer and scholar Wu Juntao 吳鈞陶, dated 17 December 1996.

[9] See, for instance, the paper by Mary McFarquhar delivered at the 26th Annual Conference of the Australian Political Studies Association, Melbourne, August 1994, entitled ‘The long revolution in China: cartoons as a case study in political communication’.

[10] Conversation with the author.

[11] Drawing a somewhat longer bow, the spirit of Sapajou certainly seems to haunt the Chinese scenes and episodes in the eventful life of Herge's Tintin, notably in Le lotus bleu, Tournai (Belgium): Casterman, 1946.

[12] Wu Juntao, ‘Chinese food and temple fairs (Zhongguo fan he miaohui), Xinmin Wanbao, 31 July 1997. The article is a commentary on two Sapajou cartoons, and responds to Hua Junwu's comment on his previous article (see above, note 8).

[13] North-China Daily News, 12/11/26.

[14] Richard W. Rigby, The May 30th Movement, Canberra: ANU Press, 1980; for the whole revolutionary period 1925-27, it is still hard to go past Harold R. Isaacs, The tragedy of the Chinese revolution, first published in 1938, with two revised editions published by Stanford University Press in 1951 and 1961; a good, more conventionally scholarly overview is to be had in Donald A. Jordan, The Northern Expedition, Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii, 1976.

[15] North-China Daily News, 21/5/27.

[16] North-China Daily News, 22/9/26.

[17] There are numerous references in the reportage and literature of the time to the remarkable resistance maintained against massive odds by the 524 Battalion of the 81st Regiment, holed up in a godown on the Suzhou Creek following their successful provision of cover for the remainder of the retreating Nationalist forces. This episode did much to create the image of China's heroic resistance to Japanese aggression, both amongst the Chinese themselves and their increasingly numerous foreign sympathisers. One particular incident was the delivery to the beleaguered defenders by a young Girl Guide, in conditions of great danger, of a Chinese flag to replace that destroyed by Japanese fire. The story was reported by Reuters in Shanghai, and attracted much attention at the time (including from the Japanese who put a price on the girl's head; she managed to escape, with assistance from the British, then theoretically still neutral). Many years later in Taiwan she privately published her own lively account of the incident: Yang Huimin, The Eight-hundred Heroes (Babai Zhuangshi), Taipei, 1976.

[18] G.E. Morrison, An Australian in China, first published by Horace Cox, London, 1895. The reference here is taken from the Oxford in Asia paperback edition of 1985, p.35.

|