|

FEATURES

The Gentle Art of Tea Drinking in China | China Heritage Quarterly

The Gentle Art of Tea Drinking in China

John Calthorpe

John Calthorpe is, in fact, John Eaton Calthorpe Blofeld (1913-1987), writer, traveller and noted populariser of Chinese religious thought. He lived in Hong Kong from 1933 to 1935 after which he worked in and travelled between Tianjin and Beiping for a time. Although he had left China the following essay on a tea tour of the country appeared in April 1939, at the time of the Japanese invasion. He continued to live and travel in China, and spent time in Beiping before the Communist takeover. From 1951, John Blofeld lived in Thailand. Among his numerous books are The Chinese Art of Tea (1985) and City of Lingering Splendour: A Frank Account of Old Peking's Exotic Pleasures (1961).

This essay is reproduced from T'ien Hsia Monthly, vol.8, no.4, April 1939, pp.319-26. Minor stylistic changes have been made in keeping with the format of China Heritage Quarterly. We have also perpetrated an anachronistic simplification by changing the spelling of the original to conform with standard Hanyu pinyin for the reading ease of latter-day students of China.—The Editor

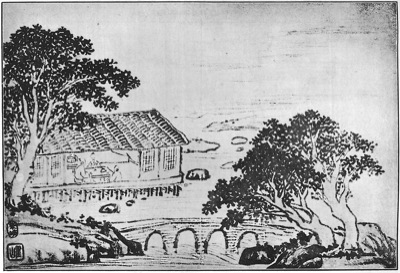

Fig.1 'Drinking Tea in a Pavilion', a painting by the Early Qing artist, Mei Qushan 梅瞿山

Of all the pastimes which the Chinese have brought to a fine art, tea drinking is one of the most typical, and it requires a highly trained mind as well as palate to appreciate it to the full. Almost every part of China has its own customs and preferences with regard to tea and, above all, the manner of drinking it. It is true that in present-day China there is no form of tea drinking so elaborate as the famous Chanoyu or Japanese Tea Ceremony, nevertheless the Chinese methods are sufficiently charming and varied to repay amply a careful study of them. Moreover, there is a book known as the Cha Jing or Tea Classic which shows us that in former centuries tea drinking in this country was developed to an even higher form of art than is the case today. Among other things that we are told in this delightful book is the fact that tea should be drunk from green transparent cups, in order that the light, shining through the cup, may reveal the delicate beauty of the colouring of the tea. Again, we read that great care should be taken when boiling the water to allow the bubbles to reach the size of lobsters' eyes, but on no account to allow them to grow to resemble those of a larger fish. To do so would be to boil the water until it had lost its original freshness or 'life'. The finest tea we are told should be infused in none but water from a bubbling spring, as no other water possesses enough life to be worthy of such tender leaves.

Although the Cha Jing is no longer a popular book, even with the most cultured Chinese scholars, yet tea drinking still persists in many parts of the country, notably Fukien, as an art rather than a means of physical stimulation or refreshment. Not only do the ways of preparation and drinking differ from province to province, but even teahouses take on vastly different characters as we go north or west from Hongkong. Moreover, closely akin to the drinking of tea as an art, is its universal use throughout the Middle Kingdom in connection with the ceremony of welcoming guests. No matter which part of the country one may happen to be in, including even Mongolia and Tibet, one can hardly enter a house without almost immediately being offered a cup of tea. The same holds true of most yamens or government offices, a great number of business firms and, especially in and around the old capital, many of the more expensive shops. Even if one's host is so poor that he cannot buy the cheapest tea at thirty or forty cents a pound, he will at least offer a cup of warm water and dignify it by the name of tea.

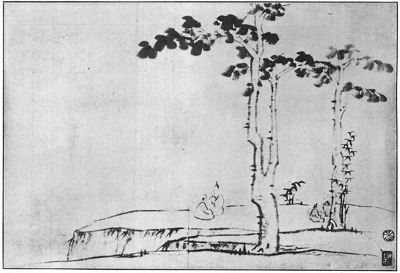

Fig.2 'Enjoying tea outdoors', another painting by the Early Qing Artist, Mei Qushan. Note the man in the right-hand corner looking after the stove for boiling tea.

Let us start from Guangdong and Hongkong in the extreme south-east and travel from province to province, drinking tea with the inhabitants as we go. Every city in Guangdong province and most villages have anything from one to many hundreds of teahouses which differ from those in other parts of China in that the eatables they provide rival the tea itself in importance. Although many of them are open all day, they are most popular in the early morning and at noon. Most of these teahouses are built several storeys high and, the higher one goes, the more one pays for one's tea—a custom which ensures that one's fellow drinkers will belong to the same economic strata as oneself, though the tea is of the same quality on all floors. The higher floors of the largest establishments are often provided with Cantonese orchestras and vocalists. Upon entering, one selects one of the small tables that fill the room, and which give it the appearance of a Parisian cafe. A waiter runs forward and, making no reference to the fact that food is also served, asks what kind of tea one wishes to have. Usually there are about eight kinds to choose from, such as 'Water Sprite', 'Black Dragon', etc. The tea is then served in one of the most ancient of Chinese ways, which has already died out in most other parts of China. That is to say no pot is used, but each guest is provided with a large cup with both lid and saucer and a very small cup without either, the former containing dry tea leaves of the variety ordered. Soon another waiter will come with a great copper kettle and pour boiling water on the leaves. After waiting for the tea to draw, one picks up the large cup and, holding it in such a way that one's fingers are not burnt (this is no mean feat as the handleless cup is always filled to the brim), one balances the lid with one finger so that some of the liquid, but none of the leaves, may fall into the little cup which is used for drinking. If one wishes for more water, one informs the ever-watchful kettle bearer by leaving the lid off the cup. One seldom goes alone to such a place, as one of the many virtues of tea is that it loosens the tongue and aids conversation, so it may be that one's friend shows his esteem by pouring out one's tea. A Cantonese custom is to show one's thanks by putting the tip of one finger on the table and then bending it to represent a man (oneself) kowtowing to the pourer. If the teahouse is visited at one of the times mentioned above, waiters will be seen hurrying about the room carrying trays covered with little dishes of all kinds or hot snacks, sweet and savoury, from which one can take one's choice as they pass the table. In this way one can add to the enjoyment of the tea by having, say, twenty mouthfuls each of a different kind of food!

Going north to the province of Fujian and the extreme north of Guangdong (the district around Shantou), we come to where the art of tea drinking has reached its highest development outside Japan. Here fine teas may cost up to eighty dollars a catty (a little over a pound in weight), and, in rare cases, may cost hundreds of dollars for that quantity. These expensive teas are sold in tiny caskets containing about an ounce, and serve as presents to esteemed friends: usually such tea is reserved especially for the most honoured of guests, but sometimes an enormously rich man will contract the habit of drinking this liquid silver daily—a habit which can become as insistent as that of opium, and which has brought more than one rich family to the brink of starvation! No ordinary pot and cups are reserved for the drinking of such tea. The pot itself is far smaller than the average tea cup, and the cups, literally the size of thimbles! It may seem strange to those who know little of the art of tea drinking that the finest porcelain is considered unworthy of such tea: simple brown earthenware is used instead. This is because the earthenware, being porous, absorbs some of the flavour of the tea. For this reason the pot is gently rinsed, but never thoroughly washed—thus, the older the pot, the better the flavour of the tea. Some pots, preferably those a hundred or so years old; which appear to be worth a few cents, may cost several hundred dollars. It is said that there is a certain kind of earthenware which absorbs so much of the goodness of the tea, that when it is very old it will produce excellent tea when nothing but hot water has been poured into it. The truth of this statement, however, the writer has been unable to verify. Tea drunk in this way has a bitter and by no means pleasant taste, but after drinking it has the virtue of producing a delicious and lingering flavour at the back of the mouth and in the throat for several minutes. It is for the enjoyment of this exquisite state that men have spent their whole fortunes! Naturally the novice will fail to appreciate the true value of such tea—he may even go so far as to dislike it at first—but the more he drinks it, the more he will come to look upon it as one of the supreme pleasures of the palate. A Fujian tea drinker of long standing will be able to tell from the taste of the tea its name, quality, approximate price, place of origin, season of picking, age and, in some cases, the type of water used—whether rain, spring, river or well water. Like all great tea drinkers he will get a threefold pleasure from the taste, colour and aroma of the tea. In fact, many Chinese teapots have the characters denoting these three virtues of fine tea inscribed in beautiful calligraphy on their outer surface [that is se 色, xiang 香, wei 味—Ed]. In most cases a host who serves rare tea in the Fujian style will boil the water himself on a small stove reserved for the purpose, as he could hardly expect the servants to understand just how long water may be heated without losing its virtue or 'life', as he would call it.

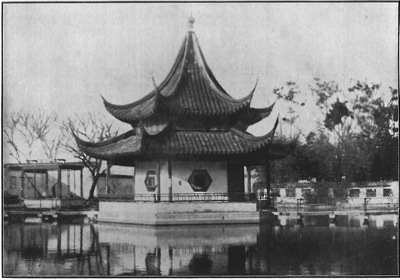

Fig.3 A teahouse recently opened in a Suzhou garden commands this lovely view.

Once more travelling northward in our quest of tea and its drinkers, we find ourselves in the culturally similar provinces of Zhejiang and Jiangsu. Here the red ('black') tea of the extreme southerners begins to give way to the green 'Dragon's Well' and 'Perfumed Morsel' brands so beloved of the northerners. In these provinces the usual method of serving tea is the one most common in the West—that is to say a teapot is employed, but the cups of course are handleless. More interesting than the way of drinking tea there, however, are the places in which it is drunk. Delightful teahouses, with white-washed walls, and black, polished woodwork, beneath fantastic upturned roofs are built on islands set in tiny ornamental lakes and approached by scarlet zigzag bridges. In many of them are separate rooms and corners for businessmen, men connected with the teaching profession and so on. They serve as delightful clubs, quite devoid of the noise and chatter of the Cantonese variety, and men sit long over their water-pipes and melon seeds, sipping their beloved tea and talking to kindred spirits in the same walk of life as themselves. Examples of such teahouses are seen at their best in the city of Suzhou, though some idea of such places may be gained from the Willow Pattern Teahouse in Shanghai.

Taking the train northward to Peking and Tianjin, we add a lot to our knowledge of tea drinking. On the train itself we may observe the modern counterpart of an ancient Chinese custom, for tea is served in extremely up-to-date looking glasses with bases made of some shiney black, unbreakable compound—a distinct product of modern science. Yet old China persists even in these glasses, for the tea is infused in the glasses themselves, and the latter have lids reminiscent of the cups used in a Cantonese teahouse! In Tianjin, tea is drunk by the working classes out of huge bowls much larger than ordinary rice bowls. These are also found in the teahouses and give rise to the Tianjin expression: 'Will you have a bowl of tea?' Incidentally and for some unexplained reason, unless because of their frequent rotundity, 'Big Teapot' is the name given in that city to the dubious gentlemen who guard the doors of the many hundreds of sing-song houses which form a kind of inner city within the Japanese concession. In Peking, various methods of serving tea may be seen: in some cases the tea is infused in a very small teapot and drunk from the spout. Da-gu or Drum singers use such pots to refresh themselves during the performance of a certain form of entertainment popular in the North, and considered to be of Shanxi origin, though it is not unlikely that it was introduced into China Proper from Mongolia or Turkestan. A number of girls sit on a platform and get up in turn to sing a kind of epic song, holding a pair of clappers in one hand and beating a drum with the other. The music is faintly reminiscent of that of the Near East and has almost a barbaric sound.

Opium smokers also favour the small teapot to drink from, as such pots make it possible to drink while lying down. In the numerous opium dens under Japanese protection, a pot is usually placed on the tray which holds the lamp and smoking accessories.

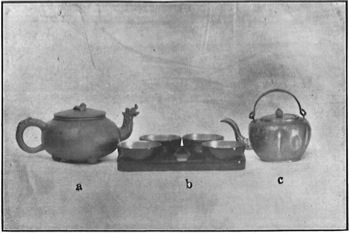

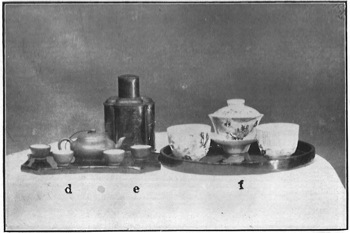

Fig.4 (a) Jiangxi earthenware pot with camel head spout; (b) Fujian tea cups, black lacquer outside and gold within; (c) Yunnan metal teapot

Fig.5 (a) Fujian-style tea-set, made in Jiangxi; (b) Shantou tea-caddy; (c) Cantonese-style tea-set, made in Jiangxi

From Peking we may sweep round through Mongolia, Sinkiang and Tibet down to the western border of Yunnan. In all these districts tea is made in a most extraordinary way. A quantity of tea leaves is cut from a brick of tea (the tea is pressed into bricks for convenience of transport by camel or mule) and boiled. The liquid is then poured into a large wooden cylinder, and butter made from camel or cow's milk is added together with some salt—the butter is often distinctly odorous—and the whole is then churned together with a hand-worked piston which is inserted into the cylinder. This continues, until the liquid froths, and it is then drunk from wooden bowls of which each man carries one upon his person. In such places tea drinking hardly ranks as a pastime, as buttered tea is one of the principal items of diet. Nor is it an art—a Mongol wishing to give you a cup of tea, but fearing the cup may be dirty, will sometimes be considerate enough to lick it clean with his tongue, and would be most offended if you should fail to drink the precious liquid, offered as a mark of hospitality and welcome, as in all parts of the Chinese dominions!

Kunming, the capital of the southwest province of Yunnan, and known to most foreigners as Yunnanfu, is literally a city of teahouses. In many streets there is one to about every ten buildings. They vary in size considerably, but, large or small, are nearly always filled to overflowing. Many of them have small ovens by the door where bakers independent of the teahouse management make several kinds of bread and buns which may be eaten with the tea. Tea costs only two coppers a bowl and is served in a kind of rough green pottery of local make which is despised as being next to worthless in the neighbourhood, but which would make the mouth of a European 'peasant-ware' enthusiast water with joy at the thought of possessing some. Kunming teahouses often provide story-tellers, singers, musicians, or at least a wireless entertainment, for their patrons, many of whom spend several hours at a stretch over their tea.

East of Kunming is the town of Dali where they have a very special way of serving tea. Usually the local pu'er tea is used, as other teas would be unsuitable. The dry leaves are first put into a small iron holder and roasted over a slow fire before being transferred to the pot for infusion. The taste of tea prepared in this way is so different from ordinary tea as to seem like another beverage. It is not unlike very weak coffee and is quite delicious. While in Yunnan, the writer saw a copper tea kettle fitted to a lamp with a chimney right through the middle of the kettle. It seems not unreasonable to suppose that such a kettle was the origin of the Russian samovar.

With our arrival in Yunnan our tea drinking tour round China comes to an end, but there still remains one thing to say about the picking of the leaves, which the Chinese in some provinces consider to be of the greatest importance. The very best tea is always prepared from leaves that are young and tender, but, as such leaves are small, the majority are left on the bushes until they become more mature in order that the total volume of the output may be greater. Thus, teas from the same district and same type of plant are graded according to the time of picking: the smaller and younger the leaves, the greater the price and the better the flavour. For this reason most tins of good tea bear two Chinese words, just below the name of the brand, meaning 'Before the Rain'. There is a mountain in Zhejiang called Dragon's Well Mountain which gives its name to a popular brand of tea grown both there and in other places, from plants taken originally from that mountain. The best plantations on the mountain belong to the monks of a certain temple who pluck some of the finest leaves while they are still tender, before the rainy season. Some of the leaves are sold and some given as presents to those who really understand the art of tea drinking and they please the recipients almost as much as would their weight in gold.

Briefly, then, the art of tea drinking is as follows. Take young and tender leaves from a famous bush and, after preparation, infuse them in the purest spring water which has been brought just up to the boil, but not beyond it. Serve it in cups, beautiful in themselves and of such a colour that it will enhance the natural beauty of the tea, or, better still, use an old brown earthenware pot which will give to the fresh tea something of the flavour of teas enjoyed in the past. Bring to it a tongue and palate well-trained in the art of appreciating good tea and concentrate on getting enjoyment from colour, flavour and scent alike. Empty the mind of all its burdens and problems and give it over entirely to the enjoyment and soothing action of the tea. Take it into the mouth while still piping hot and allow it to trickle slowly down the throat, rolling it with the tongue the while. Pause between each tiny cupful and meditate upon the delight it has given you and, as a warm glow suffuses your being, give yourself up to the serenity and quiet contentment that it brings.

Related material from China Heritage Quarterly:

|