|

|||||||||||

|

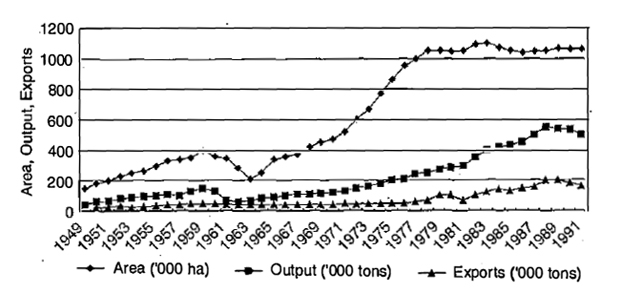

FEATURESThe Strange Tale of China's Tea Industry during the Cultural RevolutionKeith Forster'Yihou shanpo shang yao duoduo kaipi chayuan.' (In future many more tea fields should be opened up on mountain slopes.) IntroductionDuring the first decade of reform (1979-88) tea output and area yields in China rose by an annual average of 7 percent, a remarkable performance for any crop, especially a perennial Chinese analysts of the tea industry have claimed that this impressive growth was due to the reform policies introduced into the agricultural sector over this period.[2] On the other hand, in a book published in 1993, my co-author and I claimed, based on a reading of official Chinese statistics then available to us, that this growth in tea output in the post-Mao period had flowed from a massive planting campaign undertaken during the Cultural Revolution itself, with the lag-time explicable by the fact that tea bushes take approximately seven years to reach full maturity from planting' Official Chinese publications, on the other hand, claimed that tea production suffered a setback in the Cultural Revolution.[4] Official figures, listed in Table 10.1 below, belie this claim, and the growth in output during the decade is even more remarkable given the enormous effort devoted to the planting program. During the period of the 3rd Five-Year Plan (1966-70) the average annual increase in tea production was 6.2 percent, and in the period of the 4th FiveYear Plan (1971-75) 9.1 percent. Apart from the period of restoration (1949-52) and the three years 1963-65 (following the disastrous slump in output from 1960 to 1962) the average rate of increase in the 4th Five-Year Plan period exceeded any period between 1949 and 1980.[5] The final column in Table 10.1 indicates that tea exports as a proportion of output fell significantly during the period 1966-76. This trend was more than merely a reflection of China's turning away from the international market, but was also, as will be indicated below, both a policy decision to sell more tea on the domestic market and a function of low world tea prices. Table 1 Changes in China's tea cultivation area, output and exports, 1965-76

Note: In 1959 China's total tea area amounted to 401,000 ha., which was the highest post-Liberation figure until 1968. In 1963 it had fallen to 211,000 ha. A = area; O = output; X = exports; X%O = exports as a percentage of output; * change on 1964. Sources: Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo Nongyebu Jihuasi Bian, Zhongguo Nongam Jingji Daquan (1949-1986) (Comprehensive Survey of China's Rural Economy), (Beijing: Nongye Chubanshe, 1989), pp.226-7; Zhongguo Chaye Jinchukou Gongsi Jingying Shliu 1949-1993 (Compendium of China Tea Import and Export Company 1949-1993), pp.322-3.

In our book we concluded, with the assistance of a regression analysis, that 'The very rapid increase in China's tea output and average yields in the 1980s was primarily due to it rapid expansion in tea area during the Cultural Revolution rather than the impact of the reform era,' and that with the government decision of the late 1970s to stabilize national tea area, future growth in output would have to come from increasing the very low mature tea yields.[6] Because this conclusion was at odds with political orthodoxy it greatly displeased officials at the Academy of Agricultural Sciences' National Tea Institute in Hangzhou who, at international tea conferences held in Japan and China in 1991, stated flatly that our analysis was flawed, and that the future (in the form of the growth in tea output) would prove us wrong. Events, however, have not transpired in the way which they so confidently predicted, and China's tea output has remained relatively stable in the 1980s. (See Fig.1) After output hit a peak of 545,000 tns in 1988 it did not pass this figure until 1991. A record crop of 600,000 tns was picked in 1993, but production has since remained below that level.[7]  Fig.1 China's tea cultivation area, output and exports, 1949-91

Now in the possession of further statistical and anecdotal evidence concerning the tea industry during the Cultural Revolution, gleaned principally from recently officially-published yearbooks and gazetteers, as well as a research trip with my colleague to four provinces (Hubei, Sichuan, Yunnan and Hunan) and one city (Shanghai) in late 1996, in this chapter I revisit the enigmatic topic of the Chinese tea industry during the Cultural Revolution to explain further what we earlier described variously as 'phenomenal,' 'incredible' and 'mind-boggling,'[8] the planting of tea fields during that decade. My purpose here is to clarify issues which were unclear to us at the time of writing Green Gold, such as how a massive area of tea fields could be planted (for example in the four years 1973-76 360,000 ha. were added to the national area, increasing it by 60 percent), who planted it and why, and how this achievement was possible given the political circumstances of the time. The following chapter, then, sets out to explain these mysteries and, in so doing, throws light on what at first sight may appear to be a trivial issue in the context of much greater events, but one which suggests that in the madness and hysteria of the times, economic decisions could be taken which were a rational response to a perceived market situation and need, and that in this particular case politically driven mass campaigns based on the personality cult of Mao complemented rather than worked against strategic initiatives and policy directions which were in China's national interest. The massive planting of tea fields in the Cultural Revolution provided the solid platform on which the later impressive growth in output was based. The Chinese economy during the Cultural RevolutionA detailed study of the Chinese economy during the Cultural Revolution comes up, not unexpectedly, with mostly negative findings.[9] However, in gross aggregate growth rates the picture is not entirely bleak. For example, the principal targets of the 3rd Five-Year Plan (1966-70) were fulfilled during a period of the most turbulent and violent struggles of the whole decade. For the decade 1966-76 the gross value of industrial and agricultural output increased by 79 percent, the gross value of agricultural output by 51 percent and the gross value of industrial output by 95 percent.[10] These growth rates are very respectable, even if they were achieved inefficiently and had deleterious consequences. Total exports remained stagnant from 1966 until 1972, when they rose, in order to pay for the importation of complete sets of equipment from developed countries. For the decade as a whole exports increased by nearly three-fold from a very low base figure.[11] The policies of the period which had the greatest impact on the tea sector included the overall strategy for the agricultural sector of 'taking grain as the key link,' which was embodied in the campaign to 'learn from Dazhai,' the decision in 1969 to give priority allocation of steel products to the agricultural sector, the 1970 policies of developing the five small industries (iron and steel, machinery, chemical fertilizer, coal and cement) and the decision in the same year to devolve industrial enterprises run by the state to the provinces and their subordinate jurisdictions, and the withdrawal from interaction with the outside world in many spheres of life (although this trend in terms of foreign trade was less apparent during the years 1972-75). In particular, at the 1973 foreign trade work meeting Vice-Premier Li Xiannian called for an increase in the export of, among other things, native and special products under which rubric tea came.[12] In terms of administration, the tea industry during the Cultural Revolution experienced the following trends which were in no way unique to it: the amalgamation and simplification of bureaucratic agencies; a reduction in the numbers of official personnel managing the industry, and the rustication, re-education and persecution of many in their ranks; and the involvement of military personnel and rebel mass organizations in the day-to-day running of affairs. Nevertheless, more routine, ongoing changes in the management and allocation of bureaucratic responsibility over the tea industry continued to occur, as these had over the previous seventeen years. These included the cycle of the devolution and recentralization of authority as well as bureaucratic streamlining and empire-building.[13] As would be expected in a period when the superiority of the socialist system was unquestioned, during the Cultural Revolution the monopoly of the socialist marketing sector went unchallenged. In line with statements which had been issued regularly in the mid-1950s, it was stressed that tea was a category of agricultural commodity and was thus procured solely according to state plans. A national tea production and procurement conference held in July 1972 pointed out that no group or individual was permitted to go to production units to purchase tea. Production units were reminded to sell their tea to commerce departments and not directly onto the market. All involved in the industry were instructed to 'attack speculators resolutely so as to stabilize the socialist front.'[14] Furthermore, in November 1974 the State Council and Central Committee Military Affairs Commission issued a joint notice prohibiting government agencies, social groups, military units, enterprises and public utilities from going to the countryside to buy agricultural sideline crops.[15] National area and output trends [16]Mao's injunction cited at the head of this article, calling for the expansion of tea-growing area in China, made an immediate impact. In 1959 the total area of tea fields increased by a post-liberation record of 51,000 ha, an annual increase unmatched until 1965. China's tea-growing area spread north to Shandong, south-west to Tibet and northwest to Gansu. Geographically, tea was now grown in six micro-climatic regions from a longitude of 94° to 122° east, and from a latitude of 18° to 37° north.[17] In a volume concerning the economic geography of East China, published in 1959, it was noted in tire section regarding Zhejiang's tea industry that: There is still much wasted land in the hill uplands that may be planted with tea orchards [sic]. It is estimated that such tea suitable [sic] land resources in the whole province add up to more than 2 million mou [mu, or over 130,000 ha], which is larger than the present acreage.[18] For this reason there is still a great future for tea production in this province.[19] Following a disastrous decline in the national tea field area between 1960 and 1963, recovery commenced in 1964. Even despite a major restoration of 81,000 ha. in 1965 national area remained below that recorded in 1961. However, an enormous increase in tea area was recorded during the 12 year period 1965-77. Nationally, this was a 200 percent increase, or an average growth rate of over 9 percent per year. In 1968 the recorded 'area planted' recovered to the level attained in 1959, and over the three years, 1968-71, the area increased by 8 percent per year.[20] Over tire next five years (to 1976) the area grew at the phenomenal rate of nearly 13 percent per annum. In 1973, and again in the following year, 100,000 ha. of tea were planted. This was equivalent to planting the total area under tea in South India or Kenya in just one year, or Sri Lanka's total tea area in two years! The enormous growth in area over this period was followed over the next 12 years (to 1989) by a total increase of only 5 percent. The national tea area has now stabilized, and it is government policy not to enlarge it any further, although a clear pattern of the distribution of tea fields shifting inland has occurred throughout the 1980s. The administrative and logistic tasks of land preparation, nursery management and planting on this scale is mind-boggling. Indeed, the scale of the planting was akin to a major military operation. The military analogy is used deliberately, because the guiding theme of the 1970 national economic planning conference was encapsulated in the slogan, 'observe, check and implement everything from the military viewpoint.'[2l] Importantly, contemporary Chinese commentaries have not sought to deny or revise the tea area statistics for these years. The siting and quality of these plantings is another matter, however, and there has been some reference to the unsuitability of location and the crudeness of field establishment and the poor management of new gardens.[22] Official statistics show that the planting and replanting of tea during the Cultural Revolution was widespread. The tea area in five major tea-producing provinces, three medium-sized producers and one small producing province grew more than three times over the period 1965-76. (See Table 10.2). Some provinces experienced an extraordinary expansion of their tea areas. For example, during 1970-78 the tea area in Anhui province increased at an annual rate of 11.4 percent, so that by 1978 the area was 2.4 times that of 1970.[23] Table 2 [24] Tea-growing area in selected provinces, 1965-94, select years ('000ha.)[25]

* Figures prior to 1989 include tea area for Hainan Island. Some comparative pre-1949 provincial tea areas include: Hunan (88,800 ha. in 1914, and 99,980 ha. in 1936); Zhejiang (37,113 ha. in 1933); Sichuan (19,700 ha. in 1914); Guangxi (7,400 ha. In 1937); Guizhou (867 ha. in 1937). Sources: Yunnan Sheng Chaye Jinchukou Gongsi Zhi, 1938-1990 Nian (Annals of the Yunnan Provincial Tea Import and Export Company, 1938-1990) Kunming: Yunnan Renmin Chubanshe, 1993), p.209; Anhui Sheng Tongjiju Bian, Anhui Sishinian (Anhui's Forty Years), (Hefei: Zhongguo Tongji Chubanshe, 1989), p.117; Shaanxi Sheng Tongjiju Bian, Shaanxi Sishinian (1949-1989) (Shaanxi's Forty Years), (Shanghai: Zhongguo Chubanshe, 1989), p.329; Cheng Qikun and Zhuang Xudan (eds), Shijie Chaye 100 Nian (100 years of the World Tea Industry (Shangai: Shanghai Keji Jiaoyu Chubanshe, 1993), pp.76, 91, 104, 160, 175, 192-3; Zhejiang Sheng Gongxiao Hezuoshe Zhi (Zhejiang, n.p., 1995), p.188; Hunan Difang Zhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui Bian, Hunan Sheng Zhi (Hunan Provincial Gazetteers), vol. 8 (Changsha: Hunan Chubanshe, 1992), p.556.

Policy initiatives and economic incentivesWhat is clear is that after the disastrous successive falls in production from 1960 and 1962, the central authorities acted swiftly to encourage the rehabilitation of tea fields which had been neglected or abandoned during the years of famine and utter destitution. A series of incentives were introduced, none of which were abandoned completely during the Cultural Revolution, although some were modified or reduced in scope.[26] These incentives included price subsidies, advance part-payment, low-interest loans, and the supply of key products such as fertilizer and grain and scarce consumer goods such as cigarettes and cotton cloth at discount prices. On the eve of the Cultural Revolution, from late February to mid-March 1966, the State Council's Agriculture, and Finance and Trade Offices convened a national meeting on tea. Vice-Premier Li Xiannian attended and made a report. The acute discrepancy between supply and demand had not been ameliorated. It was pointed out that in 1964 China supplied only a little over 5 percent of the world's tea trade, that in 1965 the domestic market was supplied with 43,500 tns, less than half the potential market of 100,000 tns. The border tea market was supplied with 29,500 tns compared to an anticipated market of about 50,000 tns, causing great dissatisfaction particularly in Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia.[27] The meeting pointed to several important relationships in the development of tea production related to prices, and a change in market priorities was announced in that the domestic market, border sales in particular, were to take precedence over exports. The meeting raised specific suggestions concerning border tea, tea standards, prices, the planting of seedlings, grades for black tea, funds, equipment, fertilizer, pesticide machinery, refining, bonus sales and technicians. An immediate benefit to tea farmers came in the form of the increased supply of 11,000 tns of chemical fertilizer to immature tea fields, supplied by the Ministry of Foreign Trade (8,000 tns) and the Supply and Marketing Co-operative (3,000 tns).[28] The decisions made at this meeting reinforce the view that the enormous expansion of tea areas was not export-driven. With the revival of production and domestic consumption in the mid-1960s, sales policy for the industry had been revised to downgrade the importance of exports in relation to the domestic market. The 1966 conference had laid down the new guidelines. The 1973 national meeting on border tea production was even more specific when it declared that 'the domestic market is primary, the overseas market secondary.'[29] During the Cultural Revolution further concrete measures were taken which greatly assisted in the development of China's tea industry. In 1969 the All China Supply & Marketing Co-operative Society earmarked 70,000 tons of steel (essential for processing equipment), 50,000 cubic meters of timber and almost one million tns of chemical fertilizers for the industry. The production of tea machinery was included in state plans at various levels and, most significantly, a tea improvement fund was established whereby a fixed percentage of procurement funds was set aside by the procurement agency (supply and marketing co-operatives) for developing production as well as improving processing technology and training specialized personnel.[30] This decision most certainly gave great impetus to the rapid expansion of tea fields and processing capacity in the first half of the 1970s. After tea output rose substantially in 1970, providing some leeway for increasing exports, and with an increase in the international price of tea as incentive, the export company took advantage of the opportunity for China to earn increased foreign currency and shifted tea supplies accordingly. (See Table 10.1)[31] The most specific indication of official encouragement to increase tea area comes from the national tea meeting convened by the Ministries of Agriculture and Forestry, Commerce, and Foreign Trade from March to April 1974, at the height of the campaign against Lin Biao and Confucius, and attended by delegates from 17 provinces. During the conference representatives from the three ministries reported on the meeting's progress to Hua Guofeng, then the minister in the State Council responsible for the agricultural sector. Hua directed that 'tea production must be greatly developed and its rate of growth speeded up. [Production] must be appropriately centralized, and base areas established with 100 counties each producing 50,000 dan [2,500 tns].' The meeting was informed that since 1965 production had increased by 81 percent, with procurements up by 79 percent, and domestic sales doubling over the same period. Delegates discussed how to develop tea production further and raise quality. The guiding directives behind development were to be Mao's general slogan of grain as the key link and all-round development (of agriculture), and his 1958 call for more plantings on mountain slopes. The meeting discussed the principles and policies for future development, which were defined as strengthened leadership, a comprehensive plan, adapting measures to local conditions, rational distribution and a great development of production. Each locality should work out its own plan, rely on the masses, work according to natural and local conditions, make all-round preparations, rational arrangements, appropriate centralization and concentration on key points. More concretely, there was to be consolidation and improvement of existing fields, speedy transformation of low-yielding fields, active opening up of new tea-growing areas, development of new tea gardens and devotion to raising yields and quality.[32] It was later admitted that the conference played a major role in stimulating production: area increased by an average of 68,000 ha. per annum from the four years 1975-78; and the number of counties producing over 2,500 tns of tea increased from six to 20 over the same period. In 1978 these counties provided about one quarter of total procurements. Also in that year the number of specialized commune and brigade tea farms had risen to over 40,000 coveting an area of 467,000 ha, which was almost half the national area.[33] More importantly, the 1974 meeting decided that the Ministry of Foreign Trade would support tea production in a most concrete way, by allocating 5,000 tns of steel (for the manufacture of crude tea-making machinery, the repair of tea refinery equipment, machines and tools for manufacturing black tea, and to tea-blending factories in export ports), 10,000 tns of chemical fertilizer and 5 million yuan in loans. The national tea export company requested a further 6,000 tns of steel, 18,000 tns of chemical fertilizer, 200 trucks and 5 million in loan funds for 1975. The Ministry of Foreign Trade and the Bank of China chipped in with 4.5 million yuan in loans to production districts to support tea exports. In 1975 further supplies of chemical fertilizer were provided to the provinces and earmarked for immature tea fields, and steel products and machinery for processing factories was provided by the export company. And in 1976, funds were provided to invest in tea refineries, warehouses, transportation and export blending factories.[34] In sum, it appears that the provisions of funds,farm inputs and machinery and equipment played a major role in stimulating production to help satisfy domestic and international demand. Local responsesIn the following section I have relied on data of varying degrees of usefulness and specificity for six of the nine provinces listed in Table 10.2. The timing of local response to central policy varied considerably among the localities studied, and a whole series of factors including the degree of political volatility could explain these variations. ZhejiangIn March 1967, at the Zhejiang industry, finance and trade meeting there was a request made to increase the output of tea and other products by over 20 percent.[35] The setting of such a target could only mean an increase in area. In each year from 1969 to 1976 a major increase in the area of tea fields in Zhejiang then occurred, as Table 10.3 illustrates. Output almost doubled between 1970 and 1976. Accompanying this major planting undertaking, production collectives introduced fine tea strains, built retaining walls, and concentrated tea fields for more efficient management. Table 3 Zhejiang's tea-growing area and output, 1965-76

Source: Shijie Chaye 100 Nian (see sources for Table 2), p.76.

Scattered figures are available for some major tea-producing counties in Zhejiang. In Sheng county in Shaoxing district (East Zhejiang), the area of tea gardens rose from 4,587 ha. in 1966, to 5,367 ha. in 1971 and to 6,333 ha. in 1976. By 1978 tea area had increased further to 7,900 ha. Between 1970 and 1974 new linked, centralized and strip-planted (lianpian jizhong tiaozai) tea fields of over 2,733 ha. were planted on plains and hills. Between 1963 and 1977 production brigades threw 110,000 workers into building retaining walls of an average of one metre high to terrace 7.5 ha. of tea fields.[36] In 1974 Zhuji county, also in Shaoxing district, hnplemented the principle of acting according to local conditions and appropriate consolidation (yindi zhi yi, shidang jizhong), and by 1976 output broke through the 2,500 tns barrier, making it one of the tea base areas called for by Hua Guofeng in 1974. Tea area doubled from 1,387 ha. in 1965, to 2,780 ha. in 1971, and then more than doubled again to 7,167 ha. in 1976. In 1975 alone over 2,000 ha. of new tea gardens were planted.[37] In Xinchang county the tea field area in 1966 was 27,500; 1971 46,200; 1975 58,500; 1978 60,300; figures for the plucked area are provided for 1966-89.[38] In Lin'an county, situated to the immediate west of the provincial capital Hangzhou, the tea area rose from 2,227 ha. in 1965 to 3,447 ha. in 1970 and to 6,493 ha. in 1976. In 1973 the county established four fine-quality tea bush nurseries and cultivated two million seedlings.[39] In Kaihua, a mountainous and isolated county in the south-west of Zhejiang, tea field area doubled from 710 ha. in 1966, to 1,482 ha. in 1970 and then quadrupled again to 5,914 ha. in 1976. The value of the crop rose four times from 773,500 yuan in 1966 to 3,249,900 yuan in 1976 (calculated in 1980 fixed prices).[40] In East Zhejiang's Ningbo district, which is not a major tea-producer in the province, total tea area in 1965 was 2,747 ha, 3,433 ha. in 1966, 6,714 ha. in 1970, 9,620 ha. in 1975, and 10,807 ha. in 1976. Output for the same years was 712 tns, 842 tns, 1,466 tns, 3,732 tns and 4,263 tns respectively. Thus while the area rose by nearly four times over the 11 years, output rose by almost six-fold.[41] In Ningbo's Yuyao county, the tea area rose from 1,160 ha. in 1966, to 2,072 ha. in 1970, and to 2,612 ha. in 1975. Output for the matching years was 365 tns, 572 tns and 1,137 tns respectively. Between 1964 and 1966 the county government either reduced or cancelled the grain contract, or increased grain supplies to tea districts which were reclaiming tea fields.[42] HunanTea area in Hunan province rose rapidly in 1968 and then every year between 1971 and 1976. Production more than doubled between 1970 and 1976. (See Table 10.4.) Many new tea bushes were planted from seed during the Cultural Revolution in areas whose soil conditions and topography were not necessarily suited to tea. This resulted in low-yielding, low-quality fields, using local, unapproved tea varieties. The recent major contraction in the area of tea fields in the province has occurred principally in these districts and the mountain slopes have returned to forest. My informant, who was involved in the planting of tea bushes during these years, stated that educated youth participated in the planting program.[43] Table 4 Hunan's tea-growing area and output, 1965-76

Source: Shijie Chaye 100 Nian (see sources for Table 2), p.91.

HubeiUnfortunately, area figures are only available for three years relevant to this chapter. Area rose by 75 percent during 1970-75, with output increasing by about 60 percent for the same period. (See Table 10.5) in our discussion with representatives of the provincial company in Wuhan it was pointed out that 'Dazhai was influential in the plantings of the 1970s. The slogan was to build terraces in North China and to open up fields on the hillsides in the South. The slogans of the central government were to promote grains and cash crops focusing on expansion and extension services. Tea was in the forefront of cash crops - especially on the hillsides and mountains.'[44] Table 5 Hubei's tea-growing area and output, 1965-76

Source: Shijie Chaye 100 Nian (see sources for Table 2), p.216; Hubei Tongjiju Bian, Hubei Shengqing 1949-85 (The Affairs of Hubei), (Wuhan: Hubei Renmin Chubanshe, 1987), p.622.

SichuanDuring the 1970s the 'learn from Dazhai' campaign in agriculture witnessed a mass campaign to run tea farms. The 1973 provincial tea conference decided to give a five-year exemption from the agricultural tax to tea plucked from newly-planted gardens. Technical personnel were assigned to people's communes to train and assist in this endeavour.[45] Table 10.6 shows that the tea area in Sichuan nearly trebled between 1972 and 1976, while output rose by less than 30 percent. Output gains were to become apparent in the following decade. In our discussions with officials at the provincial tea company we put the question why Sichuan had experienced such extraordinary growth in output from the mid-1970s to mid-1980s (an average annual growth of 10.5 percent from 1976 to 1986). The initial response referred to the coordinated support that tea farmers had received from factory bases in terms of procurements and the provision of such key inputs as fertilizer, coal, plastic sheeting and grain. Then we asked about the massive increase in area in the years 1972-76. The reply was couched in the following terms: 'Mao's 1958 slogan was repeated in the Cultural Revolution—it had not been rescinded. Tea factories had the slogan plastered up everywhere. I was personally involved in the planting on the hillsides around Yibin. Cadres were sent out along with educated youth and peasants—but no military were involved. Mao's slogan was everywhere. We were following Mao and were therefore not under any threat from the excesses of the Cultural Revolution. We were left to get on with the job. We planted seeds of the best varieties (such as Yunnan big leaf) and cuttings for other varieties. The cuttings were transplanted from nurseries after one year. There were strict guidelines as to spacing. The planting was well done.'[46] Table 6 Sichuan's tea-growing area and output, 1965-76

Source: Shijie Chaye 100 Nian (see sources for Table 2), p.104.

YunnanYunnan province is an interesting case study because its rapid increase in tea area has been mostly a post-Cultural Revolution phenomenon. However, in the year of 1966, Yunnan planted 12,000 ha. of tea fields.[47] It is claimed that this came about as the direct result of the intervention of the provincial party secretary who responded to the centre's call for giving publicity to model fields (yangban tian) by choosing a county which had increased its tea plantings, thereby giving the signal to other places to expand their tea field area.[48] Yunnan's tea area also rose markedly in 1970 and 1974 (by a massive area of 11,000 ha), and 1975 (over 10,000 ha). So that by 1976 tea area was over double that of 1965 and nearly 75 percent more than that of 1966. In late 1970, acting on a directive of the provincial revolutionary committee, the provincial tea company devolved management of its six tea processing factories to the counties. This stimulated a great addition to the processing system because tea factories were profitable and paid taxes to local governments. In 1973 three counties prepared to build tea refineries, and this trend spread across the province like grass-fire. Clearly this would have further stimulated peasants and governments alike to grow tea and increase the tea field area.[49] As one informant put it: The masses were mobilized to plant tea. In addition, tea producers were given preferential access to grain fertilizer, coal, kerosene, and iron for processing equipment. The supply and marketing co-operatives bought all tea on offer with cash advances, so that farmers could buy inputs before harvest.[50] Table 7 Yunnan's tea-growing area and output, 1965-76

Source: Yunnan Sheng Chaye Jinchukou Gongsi Zhi (see sources for Table 2), p.209.

The almanac of the provincial tea company provides further detail on the planting of tea during this period.[51] From 1964, a contour and terrace-style planting regime was introduced at a time when the Dazhai model was propagated across the country as a model agricultural unit. The masses were mobilized to plant tea seeds on a large scale, although the quality of the plantings left much to be desired with gaps in rows and insufficient embankments. However, those fields planted by the state reclamation sector were a great improvement on the- old system of contour farming, because slopes were terraced, seeds planted into drills and covered with topsoil, and base fertilizer applied. The deficiency lay with the post-planting management regime. A saying from that time went as follows: plant in the first year, barren in the second year, and pasture in the third (tou nian zhong, er nian huang, san man biancheng fangmuchang). Much of the plantings were low-yielding fields which were to age prematurely. This situation changed somewhat after 1975 when the provincial tea company held a scientific and technology symposium, and decided to adopt the Guizhou technique of close planting.[52] In 1972 the provincial revolutionary committee stated that the bonus sales policies for tea production introduced before the Cultural Revolution would be continued. Between 1974 and 1978 the provincial tea company distributed a total of RMB 9.6 million in loans from the state ministries of Foreign Trade and Finance to support tea production, tea machinery production, cash flow, subsidies for tea machinery and tea seed transport costs, and investment for capital construction into tea processing factories. Another policy impacting on the tea industry was the tea improvement levy, which was deducted at the rate of 3 percent from the total funds for tea procurement. Fifty percent was retained by the counties, 20 percent by districts and 30 percent handed over to the province. The province was to use its share to Invest in new tea districts, while its subordinate administrations were to use their share to pay the salaries of instructors, the training of technical personnel, the holding of meetings and other expenses associated with the development of the industry. Between 1973 and 1978 this levy amounted to almost RMB 4 million.[53] Following the national tea conference in early 1974, in July of the same year the provincial bureaus of agriculture and foreign trade convened a conference with the aim of creating 12 tea bases, each producing over 2,500 tns of tea by 1980. Major responsibility for fulfilling the task was handed over to the state farm sector, and new state farms run by both the land reclamation bureau and the labour reform bureau were planned. The conference placed great emphasis on more prudent and scientific farming practices, both to renovate existing fields and in opening up new tea gardens.[54] The first county listed among the 12 base area counties was Fengqing, located in central-west Yunnan, and the site of the 1974 provincial tea conference. Its tea output had already exceeded 2,500 tns in 1974, placing it among the 15 highest tea-producing counties in China. It produced 16 percent of Yunnan's total output in that year of 10.5 percent of provincial tea field area. (See Table 10.8.) In 1965 revenue from tea production comprised 45.4 percent of total budgetary revenue. The major expansion of tea area in the county took place in 1966, before the excesses of the Cultural Revolution were felt on the production front. The only other noticeable increase occurred in 1974. In fact, Fengqing's tea industry throughout the Cultural Revolution marked time. Without detailed knowledge of the situation in the county it is difficult to judge why it should be such an exception to the general trend. The only explanation to be garnered from the written record is that in 1967 government agencies directed that the issuing of pre-procurement funds for tea be halted. However, Fengqing county continued the practice. With the supply of cotton rising in that same year, the issuing of bonus cloth coupons to tea farmers was halted, and in 1970 the bonus issue of grain was also stopped.[55] This suggests the importance of economic incentives to the growth of China's tea industry during the period, and the differences in the implementation of such incentives in various parts of the country. Table 8 Fengqing county's tea-growing area and output, 1965-76 and proportion of provincial area/output

Source: Fengqing Xian Chaye Zhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui Difang Zhi Bangongshi Sian, Fengqing Xian Chaye Zhi (Annals of Fengqing County's Tea Industry), (Kunming: Yunman Renmin Chubanshe, 1995), pp.479-81.

ShanxiIn the north-western province of Shanxi, one of the least important tea-producing provinces in China, in a mere five years tea area increased almost five fold! Both the extent and the location of this planting are extraordinary. The southern counties of Shanxi represent the northern extreme of China's tea areas (33° North, just south of the Yellow River) where the growing season is limited to between 210 and 270 days. Economic incentives clearly played a major role. Beginning in 1963 peasants were given favourable procurement prices for selling tea seeds as well as tea seed subsidies to plant new tea gardens. The 1966 national meeting seems to have had a great impact in Shanxi province. In April 1966 the provincial people's council exhorted its subordinate jurisdictions to take the lead in transforming old tea fields, and to go all out and develop new tea-growing districts and tea fields in a scientific and well-managed fashion. The relevant departments and counties were to provide financial and other support to accomplish this endeavour.[56] After the 1974 national tea conference a massive 5,520 tns of tea seeds were bought in from Hunan, Zhejiang and Anhui to plant new tea gardens in the province. As Table 10.9 reveals, the area of Shanxi's tea gardens almost quadrupled between 1970 and 1976, with virtually all the growth in area coming in the latter two years after the importation of tea seeds.[57] Table 9 Shanxi's tea-growing area and output, 1965-76

Source: Shanxi Sishinian (1949-1989) (Shanghai: Zhongguo Chubanshe,1989), p.329.

Detailed figures and information are available from two counties in Shanxi. In Pingli county, in the far south of the province, the area of tea fields was only 73 ha. in 1965. The next year it more than doubled to 173 ha. In 1975 area increased from 180 ha. the previous year to 593 ha. and then in 1976 exploded to 2,667 ha. In 1977 this massive increase continued, but by 1990 the area had fallen back to a figure lower than that in 1976. In the early stages of the Cultural Revolution, under the influence of the Dazhai model in agriculture and Mao's slogan of 'taking grain as the key link' the growing of tea was attacked because it could not fill stomachs and the tea was attacked as a 'revisionist sprout.' Tea specialist teams, established in 1964 to spread new growing techniques and popularize new seed strains, were disbanded, and large areas of tea fields were said to lay waste (although the statistics in Table 10.10 do not support this assertion). In 1968 county technicians, after failing to elicit a response from local authorities concerning their request to establish an experimental state tea farm in the county, wrote to Zhou Eniai to gain his support. Zhou's office passed the request back to the province, praising it as worthy of study. In September 1968, the month after the Jiefangjun Bao (People's Liberation Army Daily) carried Mao's 1958 slogan concerning planting more tea gardens on mountain slopes, the provincial authorities despatched two officers to the county relaying Zhou Enlai's response and three technicians were seconded to prepare for the establishment of a state tea farm. Between 1972 and 1976 1,000 tns of tea seeds were brought in from other provinces for planting (about one-fifth of the total brought into the province), and the result can be seen in the enormous increase in county area in 1976. The county government provided a subsidy of 10 fen per kg of tea seed brought into the county.[58] This brief account of what transpired in Pingli county illustrated the happy confluence of leadership cult, political correctness, policy initiative and economic incentive all playing mutually reinforcing roles.[59] Mao's 1958 slogan acted as the catalyst to initiate a mass planting campaign, in the process overcoming countervailing political trends which rebuked the development of cash crops as bourgeois and denied grain supplies to peasants who devoted their energies to developing such crops. Even the advice of despised 'white' experts (the 'stinking ninth category' of discriminated social strata) was, in this instance, taken on board. Table 10 Pingli county's tea-growing area and output, 1965-76

Source: Liu Chenghao and Dang Zhongying, Pingli Chaye Zhi (Chugao) (Pingli Tea Gazetteer [1st draft]) (April 1993), p.20.

ConclusionsIt appears from the available information that while the economic incentives which were put in place in 1963 to encourage tea farmers to expand the area under tea, and to induce peasants to grow tea as a viable crop were continued during the Cultural Revolution, if at somewhat a reduced amount in some instances, the political element—that is the renewed propagation of Mao's slogan from the Great Leap Forward—was the crucial factor in the expansion of tea area during this period. This was despite the general political and policy climate which placed excessive emphasis on grain in agriculture, viewed cash crops as 'capitalist' or 'revisionist' sprouts, and denigrated undue attention to economic development as helping to pull down the 'red flag.' Personnel working in the tea industry could thus repeat Mao's 1958 slogan, and its status rendered them virtually invulnerable to criticism for pladng undue emphasis on professional expertise, and the 1974 national tea conference reinforced the political correctness of this endeavour. Local responses to these central initiatives varied in degree and rapidity, but they and peasants in tea-growing areas both benefited from the expansion of tea fields and the building of local processing facilities for the revenue it brought in and the employment it provided. However, this rapid, unplanned and rush-planting of tea fields has left a legacy for China's tea industry. While later output increases were impressive and reflected the results of years of back-breaking labour, the low quality of the bushes and fields resulted in poor-quality tea, and has meant that a major replanting program has been required to lift the quality of China's teas to meet the consumer demands of fussier and better-off customers. The principal factors behind the rapid growth of tea fields in the chaotic period of the Cultural Revolution can be summarized as the following: 1. Continued implementation of incentive policies introduced in the pre-Cultural Revolution period from 1962-65 to revive the industry after the dramatic slump which had occurred during the years 1959-61. The original motivation behind introducing these incentives seems to have been the need to retain export markets and to guarantee supplies to this sector. 2. New policies introduced during the years 1969-71 to supply easy loans and agricultural inputs to tea farmers, and industrial materials to the processing, blending and transportation sectors to expand output and to meet unsatisfied demand in all three markets (export, border and Han domestic). 3. The revival and widespread propagation of Mao's 1958 call to plant tea on mountains which, in the context of the personality cult and mass fervour of the times, resulted in a mass movement to plant tea across the country. 4. The important role played by the 1966, 1972 and 1974 national tea meetings to set targets, principles, strategy and polices for the industry. 5. The method of planting. The planting of seeds was the only way such a large expansion of area could be accomplished in such a short time, and also explains why the quality of the planting was poor. Appendix: A note on planting tea bushesTea bushes can be planted in three main ways: from seeds, seedlings and cuttings. Planting from seeds is similar to grain in that the seed is planted in drills. The advantage in planting from seed is that it requires less labour input and avoids the necessity of raising and managing nurseries. The disadvantage lies in the fact that not all seed is viable, and unless careful selection is carried out there is no consistency in the vitality of the plant, resulting in poor output performance. In Kenya selection was carried out by placing seeds in water troughs and eliminating the light seeds which floated. Seedlings are raised in nurseries for about one year before being planted out. Plucking can commence in year three, with an economic yield return in year six and the, plant reaching maturity in year nine. Vegetative propagation (VP) of clones by taking cuttings off selected mother plants and raising these in nurseries produces high-yielding plants. After one year in the nursery holes are dug to plant out the cuttings. Plants reach maturity in year seven. Experiments undertaken in China have produced similar results.[60] This form of planting tea bushes did not commence until the late 1960s, and became widespread in 1970. The significance of the above for the purpose of this chapter is that our econometric analysis for China reveals that statistically significant yields do not commence until years six and seven and before that are negligible. Our model pools all areas over eight years old as mature. Thus, our results point to the method of planting seeds as being widespread in China, and the lag effect flowing through to output volumes in a later period. The planting of seeds also helps explain low yields, due mainly to a low survival rate among new plantings.

Notes* The author would like to thank Southern Cross University, Australia, for funding a field trip to China, Taiwan and Hong Kong between October and December 1996. Thanks are also due to my colleague Dan Etherington who took the notes of the interviews we conducted in China on this our last research trip of a joint research project which spanned ten years. Special thanks are also expressed to officials in various Chinese provincial tea import and export companies for their assistance, courtesy, hospitality and willingness to exchange views in a frank manner. I wish to make it clear, however, that the views expressed in this article are entirely my own. [1] 'Dangdai Zhongguo Shangye' Bianjibu, Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo Shangye Dashiji (Chronicles of the PRC's Commerce), vol. 2 (Beijing: Zhongguo Shangye Chubanshe, 1990), p. 837; Yunnan Sheng Chaye Jinchukou Gongsi Zhi 1938-1990 Nian (Annals of the Yunnan Provincial Tea Import and Export Company-1938-1990), (Kunming: Yunnan Renmin Chubanshe, 1993), p. 47. [2] See, for example, Cheng Qikun and Zhuang Xuelan (eds), Shijie Chaye 100 Nian (100 years of the World Tea Industry), (Shanghai: Shanghai Keji Jiaoyu Chubanshe, 1995), p. 65. [3] Dan M. Etherington and Keith Forster, Green Gold: The Political Economy of China's Post-1949 Tea Industry (Hong Kong and New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), pp. 77-80. See the note on the planting of tea bushes attached as an appendix to this chapter. [4] For example, Editorial Department of the 'Contemporary China' series (ed.), Dangdai Zhongguo De Nongzuowu Ye (Contemporary China's Cropping Industry), (Beijing: Zhongguo Shehui Kexue Chubanshe, 1988), p. 363. [5] Sun Minzhi (ed.), Zhongguo Jingji Dili Gailun (An Outline of China's Economic Geography), (Beijing: Shangwu Yinshuguan, 1983), p. 390. [6] Green Gold, pp. 102-3. The statistical analysis is found on pp. 96-102. [7] Output figures for China's tea over the years 1994 to 1997 are an enigma. While official statistics list output figures of around 590,000 tns for the years 1994 to 1996, figures from the domestic trade system for the same period estimate output at between 60,000 to 100,000 tns lower! The State Bureau of Statistics has recorded 1997 output at 610,000 tns, while the domestic trade system estimates output at 516,000 tns. See, Zhejiang Ribao (ZJRB), 5 March 1998; Chaye Xinxi (Tea Information), no. 276, 15 January 1998. For a discussion of recent trends in China's tea industry, see Keith Forster and Dan Etherington, 'Faltering Change in China's Tea Industry,' Asian Journal of Business and Information Systems, 1: 2 (Winter 1996), pp. 151-73; Keith Forster, 'China's Struggling Tea Economy,' The Tea & Coffee Trade Journal, 168: 2 (February 1996), pp. 18-27, and 'China's Tea Industry in 1996/97,' The Tea & Coffee Trade Journal (vol. 1 70, 1998). [8] Etherington and Forster, Green Gold, pp. 77-8. [9] Liu Suinian & Wu Qungan (eds), 'Wenhuadageming' Shiqi De Guomin Jingji (1966-1976) (The National Economy during the 'Cultural Revolution'), (Haerbin: Heilongjiang Renmin Chubanshe, 1986). The many failings and few achievements are set out on pp. 97-113. For other accounts of the Chinese economy during this period, see Li Chengrui, 'Shinian Neiluan Qijian Woguo Jingji Qingkuang Fenxi—Jian Lun Zheyi Qijian Tongji Shuzi De Kekaoxing' (An Analysis of China's Economic Situation during the Period of Ten Years of Internal Disorder—and the Reliability of the Statistics of the Period), Jingji Yanjiu, no. 1 (1984), pp. 23-31, trans. in Joint Publications Research Service, China Daily Report, no. 46 (7 March 1984), pp. K2-15; Chen Xuewei, 'Jingji Jianshe De Tingzhi, Daotui Jiqi Lishi Jiaoxun—Ping 'Wenhuadageming' Shinian De Jingji Jianshe' (Halts and Reversals in Economic Construction and their Historical Lessons—An Appraisal of Economic Construction in the Ten Years of the 'Great Cultural Revolution'), in Tan Zongji and Zheng Qian (eds), Shinian Hou De Pingshuo—'Wenhuadageming' Shilunji (An Evaluation Ten Years On - Essays on the History of the 'Cultural Revolution'), (Beijing: Zhonggong Dangshi Ziliao Chubanshe, 1986), pp. 156-209; Wang Nianyi, 1949-1989 De Zhongguo—Da Dongluan De Niandai (China from 1949 to 1989—A Tempestuous Era), (Zhengzhou: Henan Renmin Chubanshe, 1984), esp. pp. 355-68; Carl Riskin, China's Political Economy: The Quest for Development since 1949 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), chs. 8-10; Penelope B. Prime, 'Socialism and Economic Development: The Politics of Accumulation', in Arif Dirlik and Maurice Meisner (eds), Marxism and the Chinese Experience: Issues in Contemporary Chinese Socialism (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 1989), pp. 136-51. [10] Calculated from a table in 'Wenhuadageming' Shiqi De Guomin Jingji, p. 124. [11] Guojia Tongjiju Maoyi Wuzi Tongji Si Bian, Zhongguo Shangye Waijing Tongji Ziliao, 1952-1988 (Statistical Materials on China's Commerce and External Economy), (Beijing: Zhongguo Tongji Chubanshe, 1990), p. 502. [12] See Wu Qingtong, Zhou Enlai Zai 'Wenhuadageming' Zhong—Huiyi Zhou Zongli Tong Lin Biao Jiang Qing Fangeming Jituan De Douzheng (Zhou Enlai in the 'Cultural Revolution:' Recalling Premier Zhou's Struggle with the Lin Biao-Jiang Qing Counter-Revolutionary Cliques), (Beijing: Zhongyang Dangshi Chubanshe, 1998), p. 135. Between 1971 and 1975 China's total foreign trade trebled. Ibid., p. 137. [13] For the details, see Green Gold, pp. 64-5. [14] Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo Shangye Dashiji, vol. 2, pp. 684-5; Editorial Department of 'Contemporary China's Commerce' (ed.), Dangdai Zhongguo De Gongxiao Hezuo Shiye (Contemporary China's Supply and Marketing Co-operative Cause), (Beijing: China Academy of Social Science Press, 1990), p. 349. [15] Chi Xiaoxian, Zhongguo Gongxiao Hezuoshe Shi (Beijing: Zhongguo Shangye, Chubanshe, 1988), p. 265. [16] This section is based partly on Green Gold, pp. 77-9. [17] Cheng Qikun and Zhuang Xuelan (eds), Shijie Chaye 100 Nian (100 years of the World Tea Industry) (Shanghai: Shanghai Keji Jiaoyu Chubanshe, 1993), p. 55. [18] In 1959 tea area in Zhejiang came to just over 61,000 ha. It was only in 1973 that Zhejiang's tea area surpassed 130,000 ha. [19] Huadong Diqu Jingji Dili (Economic Geography of the East China Region), Joint Publications Research Service, 11438, 7 December 1961, p. 224. Interestingly, Zhejiang's tea area registered virtually no increase in 1959 compared to 1958. [20] The only indication of the celebration of the 10th anniversary of Mao's directive came from the province where it was issued. A full-page article concerning the Shu tea people's commune Mao had visited in 1958 and had uttered the words of wisdom was accompanied, ironically, by a photograph of a rice field. See Xin Anhui Bao, 18 September 1968. [21] 'Wenhuadageming' Shiqi De Guomin Jingji, p. 155. [22] This point was emphasized in an interview with the deputy-manager of the Hunan Tea Import and Export Company, Changsha, November 1996. [23] Teng Xuewei et al., 'Build up Confidence, Deepen Reform and Make Anhui's Tea Industry Prosper,' Chaye Tongbao (Tea Industry Journal), no. 1 (1990), pp. 1-5. [24] Compare this table with Table 5.2 in Green Gold, p.80 which relied on statistics available to us in 1991. [25] Central Henan province, which had a mere 1,400 ha. of tea fields in 1965 increased its area to almost 11,000 ha. by 1975. See Henan Sheng Jingji Shehui Fazhan Zhanlüe Guihua Zhidao Weiyuanhui, Henan Renmin Zhengfu Diaocha Yanjiushi Bianzhu, Henan Shengqing (The Affairs of Henan), (Zhengzhou: Henan Renmin Chubanshe, 1987), p. 149. [26] For details, see Green Gold, pp. 82-5. [27] Border tea (bianxiaocha) refers to brick and other re-fermented teas grown and manufactured in designated provinces and factories, and supplied to regions where there are high concentrations of minority nationalities, such as Tibet, Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia. Even today border tea remains a commodity coming under central government fixed plans and price controls. See Keith Forster, 'Tea and China's Minority Nationalities,' The Tea & Coffee Trade Journal, 162: 4 (April 1990), pp. 50-4. [28] Zhongguo Chaye Jinchukou Gongsi Jingying Shilu, 1949-1993, pp. 128-30; Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo Shangye Dashiji, vol. 2, pp. 595-6. [29] Zhongguo Renmin Gongheguo Shangye Dashiji, vol. 2, pp. 698-9; A Selection of Materials on the History of China's Supply and Marketing Co-operative, vol. 1, Part 2, pp. 351-3. [30] Chaye Tongbao, no. 3 (1989), pp. 1-5. [31] Zhongguo Chaye Jinchukou Gongsi Jingying Shilu, 1949-1993, pp. 144-5. [32] Zhongguo Chaye Jinchukou Gongsi Jingying Shilu, 1949-1993, p. 149; 'Dang dai zhongguo shangye' bianjibu, Zhonggua Renmin Gongheguo Shangye Dashiji, vol. 2 (Beijing: Zhongguo Shangye, 1990), p. 837; Yunnan Sheng Chaye Jinchukou Gongsi Zhi 1938-1990 Nian (Annals of the Yunnan Provincial Tea Import and Export Company, 1938-1990) (Kunming: Yunnan Renmin Chubanshe, 1993), pp. 22, 49, 53. [33] Editorial Department of the 'Contemporary China' series (ed.), Dangdai Zhongguo De Nongzuowu Ye (Contemporary China's Cropping Industry), (Beijing: Zhongguo Shehui Kexue Chubanshe, 1988), p. 363. [34] Zhongguo Chaye Jinchukou Gongsi Jingying Shilu, pp. 152, 154, 156, 159-60. [35] Economic Research Office of Zhejiang Province (ed.), Zhejiang Shengqing (The Affairs of Zhejiang), (Hangzhou: Zhejiang Renmin Chubanshe, 1986), p. 1052. [36] Sheng Xian Zhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui Bian, Sheng Xian Zhi (Sheng County Gazetteer), (Hangzhou: Zhejiang Renmin Chubanshe, 1989), pp. 104-8, table of area and output 1927, 1934, 1942, 1949 and select years to 1985. [37] Zhuji Xian Zhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui Bian, Zhuji Xian Zhi (Zhuji County Gazetteer), (Hangzhou: Zhejiang Renmin Chubanshe, 1993), pp. 191-2, 196-7, table of tea area and output 1949-87. [38] Xinchang Xian Zhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui Bian, Xinchang Xian Zhi (Xinchang County Gazetteer), (Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian Chuban, 1994), pp. 210-12. [39] Lin'an Xian Zhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui Bian, Lin'an Xian Zhi (Lin'an County Gazetteer), (Shanghai: Hanyu Dacidian Chubanshe, 1992), pp. 212-15. For the figures for Xiaoshan County situated across the Qiantang River from Hangzhou, see Xiaoshan Shi Nongyeju Bian, Xiaoshan Xian Nongye Zhi (Annals Of Xiaoshan County's Agriculture), (Hangzhou: Zhejiang Renmin Chubanshe, 1989), p. 134; Xiaoshan Xian Zhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui (Xiaoshan County Gazetteer Compilation Committee), Xiaoshan Xian Zhi (Xiaoshan Gazetteer), (Hangzhou: Zhejiang Renmin Chubanshe, 1987), p. 261. For the figures for Fuyang county, situated to the immediate south-west of Hangzhou, see Fuyang Xianzhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui Bian, Fuyang Xian Zhi (Fuyang County Gazetteer), (Hangzhou: Zhejiang Renmin Chubanshe, 1993), p. 251. [40] Kaihua Xian Zhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui (Kaihua County Gazetteer Compilation Committee), Kaihua Xian Zhi (Kaihua County Gazetteer), (Hangzhou: Zhejiang Renmin Chubanshe, 1988), pp. 136-9. [41] Ningbo Shi Difang Bianzuan Weiyuanhui Bian, Ningbo Shi Zhi (Ningbo City Gazetteer), (Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju Chuban, 1995), vol. 2, pp. 1314. [42] Yuyao Shi Difang Bianzuan Weiyuanhui Bian, Yuyao Shi Zhi (Yuyao City Gazetteer), (Hangzhou: Zhejiang Renmin Chubanshe, 1993), pp. 248-9. [43] Discussion at the Hunan Tea Import and Export Company, Changsha, 23 November 1996. [44] Discussion at the Hubei Tea and Jute Import and Export Company, Wuhan, 8 November 1996. [45] Sichuan Difang Zhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui Bian, Sichuan Sheng Zhi (Sichuan Provincial Gazetteer), Nongye Zhi (Agriculture), Shangce (Chengdu: Sichuan Cishu Chubanshe, 1996), pp. 292-3. [46] Discussion at the Sichuan Tea Import and Export Company, 18 November 1996. [47] However, statistics show a net increase of 7,740 ha. in 1966. See Table 10.7. [48] Yunnan Sheng Chaye Jinchukou Gongsi Zhi, p. 209. [49] Yunnan Sheng Chaye Jinchukou Gongsi Zhi, pp. 21-2, 63, 209. [50] Discussion in Kunming, 19 November 1996. [51] Yunnan Sheng Chaye Jinchukou Gongsi Zhi, pp. 49, 51. [52] Sparse planting not only reduces tea yields, but means that tea bushes cannot be shaped into hedges to assist in plucking. Additionally, it has the disadvantage of allowing the penetration of sunlight, encouraging the growth of weeds. [53] Yunnan Sheng Chaye Jinchukou Gongsi Zhi, p. 52. [54] Yunnan Sheng Chaye Jinchukou Gongsi Zhi, pp. 46, 53-4. [55] Fengqing Xian Chaye Zhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui Difang Zhi Bangongshi Bian, Fengqing Xian Chaye Zhi (Annals of the Tea Industry in Fengqing County), (Kunming: Yunnan Renmin Chubanshe, 1995), pp. 31-5, 479-81. [56] Li Pingan et al., Shanxi Jingji Dashiji (1949-1985) (Chronicle of Events in Shanxi's Economy), (Xi'an: Sanqin Chubanshe, 1987), p. 277. [57] Shanxi Difang Zhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui Bian, Shanxi Sheng Zhi (Shanxi Provincial Gazetteer), vol. 11, Nongmu Zhi (Agriculture and Animal Husbandry), (Xi'an: Shanxi Renmin Chubanshe, 1993), p. 303. [58] Liu Chenghao and Dang Zhongying, Pingli Chaye Zhi (Annals of Pingli's Tea), 1st draft (April 1993), pp. 13-15, 20. [59] For details regarding the history of the industry in Shanxi's principal tea-producing county in the Cultural Revolution, see Ziyang Xian Zhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui Bian, Ziyang Chaye Zhi (Annals of Ziyang's Tea), (Xi'an: Sanqin Chubanshe, 1987), pp. 7-9, 11. During the four years from 1974 to 1978, 1,455 tns of tea seeds were planted, and 56 commune-run and 410 brigade-run tea farms were established. About 30 percent of these tea fields were planted at an altitude of 900 metres ASL. [60] See Dan M. Etherington, 'Economic Analysis of a Planting Density Experiment for Tea in China,' Tropical Agriculture (Trinidad), 67: 3 (July 1990), pp. 248-56. |