|

|||||||||||

|

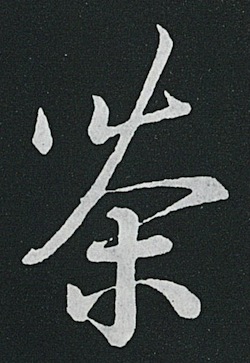

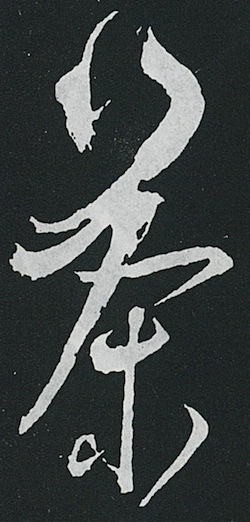

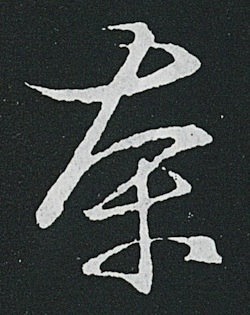

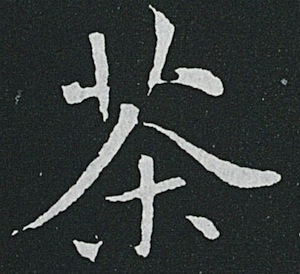

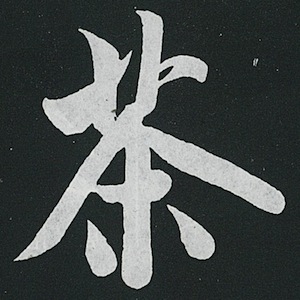

FEATURESOn Tea and FriendshipLin Yutang 林語堂 Fig. 1 'Tea', in the hand of Cai Xiang 蔡襄 (三希堂法帖) I do not think that, considered from the point of view of human culture and happiness, there have been more significant inventions in the history of mankind, more vitally important and more directly contributing to our enjoyment of leisure, friendship, sociability and conversation, than the inventions of smoking, drinking and tea. All three have several characteristics in common: first of all, that they contribute toward our sociability; secondly, that they do not fill our stomach as food does, and therefore can be enjoyed between meals; and thirdly, that they are all to be enjoyed through the nostrils by acting on our sense of smell. So great are their influence upon culture that we have smoking cars besides dining cars, and we have wine restaurants or taverns and tea-houses. In China and England at least, drinking tea has become a social institution. The proper enjoyment of tobacco, drink and tea can only be developed in an atmosphere of leisure, friendship and sociability. For it is only with men gifted with the sense of comradeship, extremely select in the matter of forming friends and endowed with a natural love of the leisurely life, that the full enjoyment of tobacco and drink and tea becomes possible. Take away the element of sociability, and these things have no meaning. The enjoyment of these things, like the enjoyment of the moon, the snow and the flowers, must take place in proper company, for this I regard as the thing that the Chinese artists of life most frequently insist upon: that certain kinds of flowers must be enjoyed with certain types of persons, certain kinds of scenery must be associated with certain kinds of ladies, that the sound of raindrops must be enjoyed, if it is to be enjoyed fully, when lying on a bamboo bed in a temple deep in the mountains on a summer day; that, in short, the mood is the thing, that there is a proper mood for everything, and that the wrong company may spoil the mood entirely. Hence the beginning of any artist of life is that he or anyone who wishes to learn to enjoy life must, as the absolute necessary condition, find friends of the same type of temperament, and take as much trouble to gain and keep their friendship as wives take to keep their husbands, or as a good chess-player takes a journey of a thousand miles to meet a fellow chess-player.  Fig. 2 'Tea' in the hand of Xu Youzhen 徐有貞 (停雲館法帖) The atmosphere, therefore, is the thing. One must begin with the proper conception of the scholar's studio and the general environment in which life is going to be enjoyed. First of all, there are the friends with whom we are going to share this enjoyment. Different types of friends must be selected for difference types of enjoyment. It would be a great mistake to go horseback-riding was a studious and pensive friend, as it would be to go to a concert with a person who doesn't understand music. Hence as a Chinese writer expresses it: For enjoying flowers, one must secure big-hearted friends. For going to sing-song houses to have a look at sing-song girls, one must secure temperate friends. For going up a high mountain, one must secure romantic friends. For boating, one must secure friends with an expansive nature. For facing the moon, one must secure friends with a cool philosophy. For anticipating snow, one must secure beautiful friends. For a wine party, one must secure friends with flavour and charm. Having selected and formed friends for the proper enjoyment of different occasions, one then looks for the proper surroundings. It is not so important that one's house be richly decorated as that it should be situated in beautiful country, with the possibility of walking around the rice-fields or lying down under shady trees on a river-bank. The requirements for the house itself are simple enough. One can 'have a house with several rooms, grain fields of several mow, a pool made from a basin and windows made from broken jars, with the walls coming up to the shoulders and a room the size of a rice bushel, and in the leisure time after enjoying the warmth of cotton beddings and a meal of vegetable soup, one can become so great that his spirit expands and fills the entire universe. For such a quiet studio, one should have wut'ung trees in front and some green bamboos behind. On the south side of the house the eaves will stretch boldly forward, while on the north side there will ne small windows, which can be closed in spring and winter to shelter one from rain and wind, and opened in summer and autumn for ventilation. The beauty of the wut'ung tree is that all its leave fall off in sprung and winter, thus admitting us to the full enjoyment of the sun's warmth, while in summer and autumn its shade protects us from the scorching heat.' Or as another writer expressed it, one should 'build a house of several beams, grow a hedge of chin trees and cover a pavilion with a hay-thatch. Three mow of land will be devoted to planting bamboos and flowers and fruit trees, while two mow will be devoted to planting vegetables. The four walls of a room are bare and the room is empty, with the exception of two or three rough beds placed in the pavilion. A peasant boy will be kept to water the vegetables and clear the weeds. So then one may arm one's self with books and a sword against solitude, and provide a ch'in (a stringed instrument) and chess to anticipate the coming of good friends.'  Fig. 3 'Tea' in the hand of Zhu Xi 朱熹 (停雲館法帖) An atmosphere of familiarity will then invest the place. 'In my studio, all formalities will be abolished, and only the most intimate friends will be admitted. They will be treated with rich or poor fare such as I eat, and we will chat and laugh and forget our own existence. We will not discuss the right and wrong of other people and will be totally indifferent to worldly glory and wealth. In our leisure we will discuss the ancients and the moderns, and in our quiet, we will play with the mountains and rivers. Then we will have thin, clear tea and good wine to fit into the atmosphere of delightful seclusion. That is my conception of the pleasure of friendship.' In such a congenial atmosphere, we are then ready to gratify our senses, the senses of colour and smell and sound. It is then that one should smoke and one should drink. We then transform our bodies into a sensory apparatus for perceiving the wonderful symphony of colours and sounds and smells and tastes provided by Nature and by culture. We feel like good violins about to be played on by master violinists. And thus 'we burn incense on a moonlight night and play three stanzas of music from an ancient instrument, and immediately the myriad worries of our breast are banished and all our foolish ambitions or desires are forgotten. We will then inquire, what is the fragrance of this incense, what is the colour of the smoke, what is the shadow that comes through the white papered windows, what is this sound that arises from below my finger-tips, what is this enjoyment which makes us so quietly happy and so forgetful of everything else, and what is the condition of the infinite universe?' Thus chastened in spirit, quiet in mind and surrounded by proper company, one is fit to enjoy tea. For tea is invented for quiet company as wine is invented for a noisy party. There is something in the nature of tea that leads us into a world of quiet contemplation of life. It would be as disastrous to drink tea with babies crying around, or with loud-voiced women or politics-talking men, as to pick tea on a rainy or cloudy day. Picked at early dawn on a clear day, when the morning air on mountain top was clear and thin, and the fragrance of dews was still upon the leaves, tea is still associated with the fragrance and refinement of the magic dew in its enjoyment. With the Taoist insistence upon return to nature, and with its conception that the universe is kept alive by the interplay of male and female forces, the dew actually stands for the 'juice of heaven and earth' when the two principles are united at night, and the ideas current that the dew is a magic food, fine and clear and ethereal, and any man of beast who drinks enough of it stands a good chance of being immortal. De Quincey says quite correctly that tea 'will always be the favourite beverage of the intellectual,' but the Chinese seem to go farther and associate it with the high-minded recluse. Tea ism then, symbolic of earthly purity, requiring the most fastidious cleanliness in its preparation, from picking, frying and preserving to its final infusion and drinking, easily upset or spoilt by the slightest contamination of oily hands or oily cups. Consequently, it enjoyment is appropriate in an atmosphere where all ostentation or suggestion of luxury is banished from one's eyes and one's thoughts. After all, one enjoys sing-song girls with wine and not with tea, and when sing-song girls are fit to drink tea with, they are already in the class that Chinese poets and scholars favour. Su Tungp'o once compared tea to a sweet maiden, but a later critic, T'ien Yiheng, author of Chuch'üan Hsiaop'in (Essay on Boiling Spring Water)[1] immediately qualified it by adding that tea could be compared, if it must be compared to women at all, only to the Fair Maku, and that, 'as for beauties with peach-coloured faces and willow waists, they should be shut up in curtained beds, and not be allowed to contaminate the rocks and springs.' For the same author says, 'One drinks tea to forget the world's noise; it is not for those who eat rich food and dress in silk pyjamas.'  Fig. 4 'Tea' in the hand of Wang Meng 王蒙 (三希堂法帖) It must be remembered that, according to Ch'alu, 'the essence of the enjoyment of tea lies in appreciation of its colour, fragrance and flavour, and the principles of preparation are refinement, dryness and cleanliness.' An element of quiet is therefore necessary for the appreciation of these qualities, an appreciation that comes from a man who can 'look at a hot world with a cool head.' Since the Sung Dynasty, connoisseurs have generally regarded a cup of pale tea as the best, and the delicate flavour of pale tea can easily pass unperceived by one occupied with busy thoughts, or when the neighbourhood is noisy, or servants are quarrelling, or when served by ugly maids. The company, too, must be small. For, 'it is important in drinking tea that the guests be few. Many guests would make it noisy, and noisiness takes away from its cultured charm. To drink alone is called secluded; to drink between two is called comfortable; to drink with three or four is called charming; to drink with five or six is called common; and to drink with seven or eight is called [contemptuously] philanthropic.' As the author of Ch'asu said, 'to pour tea around again and again from a big pot, and drink it up at a gulp, or to warm it up again after a while, or to ask for extremely strong taste would be like farmers or artisans who drink tea to fill their belly after hard work; it would then be impossible to speak of the distinction and appreciation of flavours.' For this reason, and out of consideration for the utmost rightness and cleanliness in preparation, Chinese writers on tea have always insisted on personal attention in boiling tea, or since that is necessarily inconvenient, that two boy servants be specially trained to do the job. Tea is usually boiled on a separate small stove in the room directly outside, away from the kitchen. The servant boys must be trained to make tea in the presence of their master and to observe a routine of cleanliness, washing the cups every morning (never wiping them with a towel), washing their hands often and keeping their finger-nails clean. 'When there are three guests, one stove will be enough, but when there are five or six persons, two separate stoves and kettles will be required, one boy attending to each stove, for if one is required to attend to both, there may be delays or mix-ups.' True connoisseurs, however, regard the personal preparation of tea as a special pleasure. Without developing into a rigid system as in Japan, the preparation and drinking of tea is always a performance of loving pleasure, importance and distinction. In fact, the preparation is half the fun of the drinking, as cracking melon-seeds between one's teeth is half the pleasure of eating them. Usually a stove is set before a window, with good hard charcoal burning. A certain sense of importance invests the host, who fans the stove and watches the vapour coming out from the kettle. Methodically he arranges a small pot and four tiny cups, usually smaller than small coffee-cups, in a tray. He sees that they are in order, moves the pewter-foil pot of tea-leaves near the tray and keeps it in readiness, chatting along with his guests, but not so much that he forgets his duties. He turns round to look as the stove, and from the time the kettle begins to sing, he never leaves it, but continues to fan the fire harder than before. Perhaps he stops to take the lid off and look at the tiny bubbles, technically called 'fish eyes' or 'crab froth,' appearing on the bottom of the kettle, and puts the lid on again. This is the 'first boil.' He listens carefully as the gentle singing increases in volume to that of a 'gurgle,' with small bubbles coming up the sides of the kettle, technically called the 'second boil.' It is then that he watches most carefully the vapour emitted from the kettle-spout, and just shortly before the 'third boil' is reached, when the water is brought up to a full boil, 'like billowing waves,' he takes the kettle from the fire and scalds the pot inside and out with the boiling water, immediately adds the proper quantity of leaves and makes the infusion. Tea of this kind, like the famous 'Iron Goddess of Mercy,' drunk in Fukien, is made very thick. The small pot is barely enough to hold four demi-tasses and is filled one third with leaves. As the quantity of leaves is large, the tea is immediately poured into the cups and immediately drunk. This finishes the pot, and the kettle, filled with fresh water is put on the fire again, getting ready for the second pot. Strictly speaking, the second pot is regarded as the best; the first pot being compared to a girl of thirteen, the second compared to a girl of sweet sixteen, and the third regarded as a woman. Theoretically, the third infusion from the same leaves is disallowed by connoisseurs, but actually one does try to live on with the 'woman.' The above is a strict description of preparing a special kind of tea as I have seen it in my native province, an art generally unknown in North China. In China generally, tea-pots used are much larger, and the ideal colour of tea is a clear, pale, golden yellow, never dark red like English tea.  Fig. 5 'Tea' in the hand of Mi Fu 米芾 (苕溪詩) Of course, we are speaking of tea as drunk by connoisseurs and not as generally served among shopkeepers. No such nicety can be expected of general mankind or when tea is consumed by the gallon by all comers. That is why the author of Ch'asu, Hsü Ts'eshu, says, 'When there is a big party, with visitors coming and going, one can only exchange with them cups of wine, and among strangers who have just met or among common friends, one should serve only tea of the ordinary quality. Only when our intimate friends of the same temperament have arrived, and we are all happy, all brilliant in conversation and all able to lay aside the formalities, then may we ask the boy servant to build a fire and draw water, and decide the number of stoves and cups to be used in accordance with the company present.' It is of this state of things that the author of Ch'achieh says, 'We are sitting at night in a mountain lodge, and are boiling tea with water from a mountain spring. When the fire attacks the water, we begin to hear a sound similar to the singing of the wind among pine trees. We pour the tea into a cup, and the gentle glow of its light plays around the place. The pleasure of such a moment cannot be shared with vulgar people.' In a true teal love, the pleasure of handling all the paraphernalia is such that it is enjoyed for its own sake, as in the case of Ts'ai Hsian, who in his old age was not able to drink, but kept on enjoying the preparation of tea as a daily habit. There was also another scholar, by the name of Chou Wenfu, who prepared and drank tea six times daily at definite hours from dawn to evening, and who loved his pot so much that he had it buried with him when he died. The art and technique of tea enjoyment, then, consist of the following: first, tea, being most susceptible to contamination of flavours, must be handled throughout with the utmost cleanliness and kept apart from wine, incense, and other smelly substances. Second, it must be kept in a cool, dry place, and during moist seasons, a reasonable quantity for use must be kept in special small pots, best made of pewter-foil, while the reserve in the big pots is not opened except when necessary, and if a collection gets mouldy, it should be submitted to a gentle roasting over a slow fire, uncovered and constantly fanned, so as to prevent the leaves from turning yellow or becoming discoloured. Third, half the art of making tea lies in getting good water with a keen edge; mountain spring water comes first, river water second, and well water third; water from the tap, if coming from dams, being essentially mountain water and satisfactory. Fourth, for the appreciation of rare cups, one must have quiet friends and not too many of them at one time. Fifth, the proper colour of tea in general is a pale golden yellow, and all dark red tea must be taken with milk or lemon or peppermint, or anything to cover up its awful sharp taste. Sixth, the best tea has a 'return flavour' (hueiwei), which is felt about half a minute after drinking and after its chemical elements have had time to act on the salivary glands. Seven, tea must be freshly made and drunk immediately, and if good tea is expected, it should not be allowed to stand in the pot for too long, when the infusion has gone too far. Eight, it must be made with water just brought up to a boil. Nine, all adulterants are taboo, although individual differences may be allowed for people who prefer a slight mixture of some foreign flavour (e.g., jasmine or cassia). Eleven, the flavour expected of the best tea is the delicate flavour of 'baby's flesh'. In accordance with the Chinese practice of prescribing the proper moment and surrounding for enjoying a thing, Ch'asu, an excellent treatise on tea, reads thus:

From The Importance of Living, Melbourne: Heinemann, 1946, pp.239-249.

|