|

FEATURES

Tempest over Teapots | China Heritage Quarterly

Tempest over Teapots:

The Vilification of Teahouse Culture in Early Republican China

Qin Shao 邵勤

The College of New Jersey

Qin Shao is Professor of History at the College of New Jersey. She is also the author of Culturing Modernity: The Nantong Model, 1890-1930, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004, and 'Waving the Red Flag: Cultural Memory and Grass-roots Protest in Housing Disputes in China', Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, vol.22, no.1 (Spring 2010): 197-232. Her latest book project is titled Shanghai Gone: Demolition and Defiance in a Chinese Megacity.

This article is reprinted with the kind permission of the author and the editors of The Journal of Asian Studies. It originally appeared in that journal in 1998 (see vol.57, no.4 [November 1998]: 1009-41). A PDF version of the article is available here. Note that we have retained the style of citation and orthography of the original introducing only minor changes.—The Editor

The Chinese teahouse was one of a few traditional institutions of sociability whose wider social and cultural appeal overshadowed its primary business. Historically, it was closely woven into the fabric of Chinese life. In many communities the teahouse served as a center of information, a locus of leisure and social gatherings, an occasional office and marketplace for many practitioners, and an arena where various social forces competed for status and influence. Urbanization in the late Qing dynasty further contributed to the growth of teahouses, especially in the Yangzi River region (Suzuki 1982; Yan 1997, 17). However, while teahouses continued to flourish in the early Republic, teahouse culture became a target—a constant target in some areas—of social critics. Why this tempest over teapots?

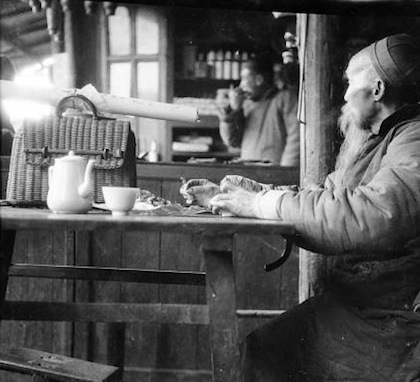

Fig.1 Robert Larimore Pendleton, Outside Hopingmen to Maikouchiao, Nanking [Nanjing]: In the tea shop, 1931-32. From the American Geographical Society Library, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries.

Teahouses have been a frequent topic of Chinese popular literature (Lao She 1980; Yu 1976; Zhuo 1978). Japanese have written widely about the Chinese teahouse since the nineteenth century (Nakamura 1899; Koubai 1920, 248-359; Takeuchi 1974; Suzuki 1982; Nishizawa 1985, 1988). Recently, a number of Western scholarly works on Chinese tea, the tea industry, and urban history have touched briefly upon the culture of the teahouse (Strand 1989, 32, 145, 154, 155; Smith 1991, 53-54; Lu 1995, 103-4). To date, however, there has been no study that takes as its central theme the changing image of teahouse culture in the life of a particular community.

This study focuses on teahouse society and culture in Nantong County, Jiangsu Province, in the early Republican period.[1] It locates Nantong teahouses within the context of a newly emergent, Western-oriented culture represented by a rising elite class of urban professionals, social reformers, and modern-style intellectuals. Attuned to modernity, these new cultural elites were disdainful of the traditional 'decadent' teahouse and everything it stood for. Through their control of local newspapers, they mercilessly attacked the teahouse and its culture as outmoded and harmful to the Republican order. Denigrating teahouses and their patrons as the uncouth 'other,' the new elites sought to define for themselves a distinctive cultural identity. In the meantime, they refashioned the concept of leisure and promoted new public spaces such as sports stadiums and parks. While such promotion did not directly undermine the appeal of teahouses to those on the lower echelons of society, it did serve as a new measure of the changing social boundaries of the time: the stratified leisure activities in their physical spaces, types, and images embodied the distinction between modernity and tradition.

Focusing on these conflicting forces—teahouses as traditional public places and the new cultural elites and modern media that tried to police the public arena—this study sheds light on emergent social and cultural tensions in early Republican China. It further illuminates the relationship between modernization and the intensified demand for popular cultural outlets. Finally, it explores the role of public spaces and the mass media in the making of modern China-topics which have increasingly engaged the attention of scholars in the China field.[2]

Teahouses and Urban Development

The great popularity of teahouses in Nantong was mainly a late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century phenomenon, closely linked to the urbanization and modern development of the region. To be sure, teahouses existed previously in both Nantong city, the seat of the Tong prefecture prior to 1911, and nearby rural towns; but they were few in number.[3] Lying north of theYangzi River, Nantong's economic and urban growth was not as advanced as that in the Jiangnan region to the south.[4]

The Taiping uprising was an important moment for the economic and urban development of Nantong, especially where the popularity of tea was concerned. Disturbed by the social upheavals in the Yangzi region and attracted by the relative peace in Nantong, many people from Jiangnan, Zhejiang, and Anhui, including merchants from Huizhou, that part of Anhui known for high quality tea, began to- migrate to Nantong. The Anhui people brought with them the 'Huishang' (Hui merchant) tradition and engaged in trade, mainly in qianzhuang (old style banking), pawn shop, tea shop, and other retail business. By 1900 there were eleven tea shops in Nantong city and more than twenty in nearby towns. Anhui tea dominated the Nantong market until 1912, when famous Zhejiang teas, such as Longjing, were introduced (Yu 1982, 39).[5] The success of the Anhui merchants brought more apprentices to Nantong and the migration continued, in fact speeded up, in the first two decades of the twentieth century. The influence of those Anhui merchants on Nantong's commercial and urban development in general and tea culture in particular cannot be overstated. As a Nantong saying goes, 'Without Anhui [merchants] there would be no town' (wuhui bucheng zhen) (Interview 7).[6]

Paralleling this commercial migration was the internal growth of markets, towns, and cities in the Nantong region. Nantong was historically known for its cotton and salt production. Local towns and markets were usually formed around centers of cotton goods exchange and salt manufacturing.[7] The most significant change, however, came after 1895. That year Zhang Jian, a reform-minded jinshi degree holder who had resigned from the Hanlin Academy to engage in local affairs in his home area, began to build the Dasheng Cotton Mill, the region's first modern factory, in Tangzha, a town near the city of Nantong. Driven by the trends of local self-government and modernity at the time, Zhang Jian and other local elites built in the following two decades more than a dozen new factories in the vicinity, and created a modern transportation and communication system (highways, bus and steamship companies, post offices, and telephone companies), along with a modern banking system and professional and educational institutions.[8]

The local elites also changed the face of Nantong city. The old city, with three gates on its eastern, western, and southern sides, had as its most prominent feature a downtown crossroad. One road connected the Eastern and Western gates, along which, on the eastern side, were arrayed stores and shops. The other road led to the Southern Gate, running through a residential area. From 1914 to the early 1920s a new downtown commercial area was constructed outside the Southern Gate, conspicuously adorned with Western-style office buildings, apartments, hotels, theaters, and parks. In 1922 the ancient city walls were demolished. From 1894 to 1929 the city burgeoned in area from less than 3 sq km to more than 6 sq km (Nantong xingzhengju 1929: zazhu, 8; Shao 1997, 103-11). In the process, outsiders came to work in Nantong. The number of households in the city increased from 2,902 in 1910 (Fan 1964, 1/hla) to over 4,000 in 1929 (Nantong xingzheng ju 1929: zazhu, 8). By the late 1910s Nantong gained nationwide reputation as a 'model county' of modernity and local self-government, becoming something of a tourist attraction (Shao 1997).

The improved transportation and communication system, a booming population, enlarged city space, and the promotion of Nantong's model image created a unique historical moment for the further commercialization of the local economy. Among other things, a cotton market formed outside the Southern Gate in the early 1910s as a periodic fair turned into a daily bustle. More than one thousand merchants, retailers, and peasants gathered there every morning to exchange cotton and other goods (Zhang and Yang 1992, 7). In addition, a new market was built within the city near the Southern Gate in the early 1920s. While wealthy locals as well as outside merchants invested in Nantong's major industrial and commercial projects such as factories and banks, local residents also capitalized on new opportunities. For instance, Southern Main Street (Nandajie), previously a residential area but now a direct link to the new downtown development outside the Southern Gate, was rapidly commercialized. Those who grew up in that period remember how residents on Southern Main Street broke the walls and expanded the front doors of their houses to start small businesses-including teahouses. Indeed, Southern Main Street soon replaced Eastern Street as the business center of the old downtown, and its real estate value soared accordingly (Interview 2).

Archival records indicate that eighteen teahouses were added to the map of Nantong city between 1900 and 1930 (NGSLD 1952 E-1024: 324, vols. 254-56). This figure can only be considered an approximation, however, since oral histories reveal that in the mid-1920s at least forty teahouses existed within the city—along with numerous others outside the city gates and in the surrounding rural towns.[9] The teahouses on Eastern Street, where cotton and silk shops were concentrated, served as gathering points for shop customers and retailers. A number of grocery and department stores were located on Southern Main Street, along with bookstores, stationery shops, and printing offices. Teahouses there were patronized by shoppers from nearby villages and towns. Teahouses were also located in small lanes and alleys among the neighborhoods. Outside the city on the western side was a new river port where several vital local communication lines crossed. The teahouses there were for boat owners, carriers, porters, and dockers. Teahouse patrons outside the southern gate included daily visitors to the cotton market (Zhang and Yang 1992, 7). As well as serving specific occupational constituencies, all these teahouses, within the city and without, were also frequented by local residents.

Nantong's teahouses—or 'chaguan' could be divided into three types. One provided dim sum (dianxin—'heart's delights') along with tea, and was considered the most formal. Another was called 'qing chaguan', meaning pure teahouse, where tea was nominally the only thing served, though patrons could bring with them dim sum or other kinds of food if they wished. In fact, however, some of these 'pure' teahouses also served simple pancakes (bing) and oil pastries (youbing), which were less expensive than dim sum.[10] These two types of teahouses had varying names, including 'chalou' (tea chambers), 'chashe' (tea societies), and 'chayuan' (tea gardens).[11] Regular patrons generally referred to the teahouses by their owner's name, such as Li's teahouse, Pan's teahouse, and so on. Teahouse waiters had a common title: cha boshi—'tea doctor'—a term that can be traced back to the Tang and Song dynasties (Meng 1957, 2/16; Hanyu dacidian 1993, 9/382; He 1994, 155-56).[12]

A third type of Nantong teahouse was the 'tangshui luzi' (water stove) or 'laohu zao' (tiger stove—a huge stove to heat water). Its main function was to supply hot water for local residents. As in Shanghai and elsewhere (Lu 1995, 103-4), some of Nantong's tiger stoves also served tea when space permitted. Such tiger stoves cum teahouses were rather small and crudely equipped, offering inexpensive tea (made with tea powder and stem instead of tea leaves) to the passersby. A few provided bath facilities as a sideline business in summer when the demand for hot water was low. It was also common for the tiger stove teahouses to retail cigarettes and cookies and other snacks. Most of the tiger stoves were mom and pop businesses. Only a few hired helpers; in one such case it was because the owner was a widowed woman (NGSLD 1952 E-1024: 324, vols. 254-56). There were also street tea pedlars, flourishing especially during local festival events and periodic market fairs, but the available source material on such pedlars is scarce. This study thus includes only the first three types: teahouses with dim sum, pure teahouses, and tiger stove teahouses.

A Mirror of Social Change

Teahouse culture had both historical and local attributes. While some of its characteristics transcended temporal and spatial boundaries, the culture itself clearly changed over time and varied in different local settings. Popular literature has provided some conflicting images of the Chinese teahouse—a tension-filled site, as irn Lao She's famous play, and a leisurely, friendly locus, as in most travel guides. Closer examination of Nantong teahouses helps illuminate the complexity of this multilayered social institution.

Historically, the culture of tea-drinking embraced both the highbrow and the lowbrow. In the Tang dynasty, tea drinking was the subject of poetry, symbolizing the high culture of the well established (Schafer 1962, 137, 149). With the rising popularity of commercial teahouses in major urban centers of Song China, teahouse-going became part of the commoner's life (Freeman 1977, 159, 160; Gernet 1988, 36, 47-49). Tea culture was further polarized in the Ming dynasty. On the one hand, there was 'wenren cha' (literati tea), a highly refined art for character molding, and, on the other hand, there was 'shumin cha' (commoner tea), supposedly merely for thirst relief (Wu 1996, 188).[13]

Teahouse culture reflected this distinction. In the highly commercialized cities of Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces in the late-Qing dynasty, some teahouses, tastefully furnished, were elite literary establishments; others, lavishly decorated, were merchants' social institutions; and still others, crudely equipped, were lower-class gathering places (Suzuki 1982, 530). Treating teahouse culture as an abstract entity, one could indeed conclude that teahouses, like a stew with many ingredients, accommodated people from all walks of life, from nobility to street wanderer (Takeuchi 1974, 4; Amano 1979, 360; Lao She 1980, 82; Evans 1992, 141, Li 1993, 80), thus conveying the prevalent notion of teahouse equality.[14] However, concrete study of teahouses shows that the institution itself was stratified according to the status of its customers. Indeed, the case of Nantong teahouses indicates that social division and exclusion existed within as well as between individual teahouses.

Unlike big cities such as Yangzhou, Nantong did not have refined, elegant commercial teahouses as elite literary establishments. Though teahouses were supposedly open to everyone—except women—as regular patrons,[15] for reasons discussed below, local notables, refined scholars, and upper-middle-level merchants consciously refrained from visiting teahouses. Teahouse patrons in Nantong were not a blend of the high and lower classes, but a mixture of those below the middle class. They included shopkeepers, their business partners and clients, retailers, itinerant entertainers, city dwellers, brokers, policemen, gangsters, peasants, and other types of working men.[16] Nor did these separate strata necessarily mix in any given teahouse. Of the three categories of teahouses mentioned earlier, the tiger stove teahouses were mainly for working men, while frequent visitors to the teahouses serving dim sum usually had to have some regular income. The pure teahouses were known as places of local entertainment, principally storytelling and folk music, which attracted many city dwellers.

Some teahouses were more respected than others, depending on the status of their owners, the location and ambiance, the types of patrons they attracted, and, related to this, the sideline business, if any, they promoted. Before the civil service examination system was abolished, the Luo Teahouse, near the prefectural yamen where the Examination Hall (Gongyuan) was located, commanded a certain amount of respect because among its occasional patrons were scholars and students who came to take the examinations, while the teahouses near the red light district in Dongnanying were avoided by self-righteous townspeople (Interview 2). The quality of the tea also mattered, as did the utensils used for serving it, i.e., whether the teapots were purple sand earthen pottery from a well-known craftsman of Yixing County of Jiangsu Province, a place known for producing the best teapots in China, or bronze antique ware with a touch of ancient Shang and Zhou culture, or refined porcelain ware, or ordinary pots, cups, and rice bowls.

Within a teahouse, the arrangement of seats and tables was of social significance, as typified by the existence of the 'zhuzuo' (master table). This table was often set up either in the center of the teahouse or in the corner farthest from the front door, away from traffic. It was considered the most honored and prestigious spot in the teahouse. An old-fashioned wooden armchair (taishi yi) was often set up in the center facing the door, with additional chairs placed on either side of the table. The table itself was made of hardwood. Placed on the master table were gold-trimmed antique teapots, while other tables had simple bowls or teapots. Waiters would refill the antique teapots first. The master table was reserved for powerful patrons and special clients; regular customers knew the rules and never dared to occupy it. Such master tables existed in Lao She's Teahouse (1980, 16), in the teahouses of contemporary Hong Kong (Barry 1994, 213), and in the teahouses of early twentieth-century Nantong, though their arrangement might vary. In the early 1920s, a local army officer in Erjia town had monopolized a particular master table. One day a young man from outside the town insisted on sitting there despite a warning from the tea doctor. The result was a fierce brawl between the young man and the officer's bodyguards. Tables were overturned and chairs were thrown; teapots were broken and blood was shed. The young man barely escaped with his life (Zhang and Yang, 1992, 8).

Thus, teahouses were not places that automatically produced instant friendships or provided sanctuary for the 'hodge-podge of humanity' that made the stress of the real world give way to a remarkable sense of serenity and harmony, as some observers have suggested (Evans 1992, 141; Li 1993, 80-81). Teahouse equality was limited. Nantong teahouses were in a sense products of social exclusivity—for example, while women were not welcomed in teahouses, teahouses were in turn shunned by elites. Like the larger society, the teahouse recreated and reinforced social barriers. This should not come as a surprise since studies on consumption habits have indicated that the division between the high and lower classes and even that between God and man is typically expressed through food and drink (Forster and Ranum 1979, xii; Soler 1979, 127; Schivelbusch 1992, 79).[17]

Teahouses as a microcosm of the society mirrored social change, which was especially evident in times of major upheavals, as in the case of the early Republic. The rapid change of that time brought social and political dislocation to many people. Previous class boundaries were being shaken and reconstructed. Teahouses both reflected and shaped such reconstruction. A cogent example is provided by the teahouse operators. To them, teahouses were not merely a source of commercial income, but a power zone within which they could seek to influence community affairs. Their background and experience not only reflected certain characteristics of Nantong teahouse culture, but also the struggle to deal with the changing times.

Pan Yinzhou was a yamen bounty hunter (pu kuai) before 1911, which was considered a lucrative post (fei chai). A local head of the Green Gang, he went into business after 1912, buying a teahouse, a restaurant, and a bathhouse, all located in the old downtown area. His teahouse, with almost thirty tables, was the largest on Southern Main Street. While Zhang Jian was concentrating on developing the new downtown area outside the Southern Gate, Pan expanded his influence inside the gate, setting up a protection business among small shop owners on South Main Street. When disputes over rent, business space, pedlars, and other matters occurred among shopkeepers or with outsiders, Pan acted as a broker. He visited these shops regularly with his bodyguards to collect his share of the proceeds. His business was not considered upscale. His manner was said to be lower class, which seemed clear from his body tattoos. While local elites and professionals did not care to socialize with Pan and excluded him from certain community events, he used his business to define his own personal realm of social exclusivity. He would thus, for example, close his bathhouse to the public when important power holders came to bathe (Interview 5). Clearly, Pan used his teahouse and other businesses to create a sphere of influence, which not only augmented his existing status but also substantially extended his network of personal contacts. Not necessarily respected, Pan nevertheless became influential in his own right.

Nor was Pan Yinzhou alone in this. Because teahouses were centers of community life, their operators often assumed a certain degree of authority as unofficial community leaders. They may not have been liked, but they were needed. People turned to them for problem solving. Some even proved to be popular. Teahouse owner Huang of Hongqiao township gained the nickname 'Half-Street Huang' (Huang banjie) because he controlled the entire eastern part of the town. Once sued for beating a customer, Huang got the townspeople to sign a petition that was to be sent to the county magistrate, accusing the unfortunate customer of being a gangster (Xinbao 27 September 1917, 7). One could argue that Huang was a bully; but broad support for him among local townspeople may have been his reward for protecting ordinary folks, as some teahouse owners even dared to challenge local well-to-do scofflaws. In Changquan town, for example, a teahouse operator once tied up a man of property for having blackmailed another townsperson (Xinbao 14 December 1917, 7). Resorting to forceful means, he nevertheless stood up for the oppressed. These stories indicate that such people had considerable standing within the community. Like the publicans of the Paris café described by Haine, they were 'social entrepreneurs' as well as shopkeepers (1996, 118).

The influence of teahouse owners came from a number of channels. One was their broad network connections, especially with traditional social organizations like underground gangs and secret societies, as in the case of Pan. Another was their access to information. Teahouses were information centers and forums where customers would come to gossip, to exchange news, and to offer their opinions. Their conversational topics could range from national issues to local tax policy to more personal concerns (Xinbao 3 November 1918, 6). Information about community affairs, including intimate details of interpersonal relationships and family matters, was useful capital. It could be exploited to benefit some and harm others. By constructing a power zone based on business contacts and opportunities and operating mostly outside the mainstream of the local elite circle, teahouse owners, most from humble origins, could strive to maintain and improve their socioeconomic situation in a highly unpredictable world.

While teahouse operators could hope to gain status in the community, some members of the former elite were severely disadvantaged by the changing times and had little hope of regaining their lost social standing. They escaped to teahouses to look for comfort. One group of regular teahouse patrons in Nantong were city dwellers, or 'xiao shimin' ('little city people') (Link 1981, 5), of which one segment consisted of those from declining landlord and gentry families, the so-called poluohu, with a bit of money and plenty of time, but without formal occupation. Social change in previous decades had squeezed them out of their regular loop. Some of them formerly lived in the countryside but moved to nearby towns or cities after their families lost land and influence in rural communities. Typically they were literate or semi-literate, but had never learned any practical skills. Mentally, they were more attached to the past than to the uncertain present, which contributed to their withdrawal from the community. They lived on the diminishing returns from inherited property, mostly land or houses as well as cash from selling off family heirlooms.

To those from such downwardly mobile families, the teahouse helped them forget about and also absorb the shock of social change. The relatively informal and relaxing atmosphere in teahouses suited the elements déclassés well. They could while away their time, finding ready sympathy from others who shared their plight. Occasionally, they could even sell their literacy skills, enabling them to earn some money and feel useful. Teahouses thus lent their lives a certain routine and coherence and, perhaps more importantly, a sense of control over their own associations and activities, even as other things in their lives seemed to be falling apart.[18] For example, Qu Du was the semiliterate son of a Nantong landlord family which had begun its decline before his birth. Unable to manage the remaining land in the family as a rental property, he sold it piece by piece. After he became addicted to gambling he first sold his antiques, then his house. Eventually, in the late 1930s, he lost everything and became a street beggar. Before that, however, he had been a regular teahouse-goer for about twenty years. Sometimes he would write letters and prepare contracts for other teahouse patrons, charging a small fee for his service (Interview 5).[19]

Similar in situation to Qu were those who had held low-level official or semi-official positions in the late Qing dynasty but whose jobs were terminated due to institutional and other changes. Unable to make a fresh start, some looked for comfort to the teahouses. A local tax collector named Ji lost his job during a famine at the end of the Qing dynasty. He had few savings to live on and received a small monthly allowance from one of his uncles, a military officer in the Republican government. Ji was a loyal teahouse customer who frequented the same establishment for decades (Interview 1). For city and town dwellers like Ji and Qu, going to teahouses was an addiction, a morning ritual without which their daily routine was incomplete. Their stylized lives were captured in a saying that circulated in Nantong in the 1920s: 'Teahouse during the day, bathhouse in the evening; skin surrounds water in the morning, water surrounds skin in the afternoon (baitian chaguan, wanshang zaotang; shangwu pi bao shui, xiawu shui bao pi)' (Interview 1).

The teahouse appealed to these and other city dwellers for other reasons as well. It was perhaps one of the most affordable public social spaces. For three to ten copper coins, one could easily pass two to three hours. For an additional two to five copper coins, one could get a couple of dumplings or other dim sum from nearby bakeries and restaurants. If a patron had to leave for a while, so long as he left his teapot uncovered his seat would be reserved and he could come back without paying extra—a practice that uniquely fitted the teahouse, since one could not drink tea for several hours without visiting a restroom, with which few teahouses were equipped. The teapots on the tables were filled periodically and would be collected only when they were lidded (Interview 1).

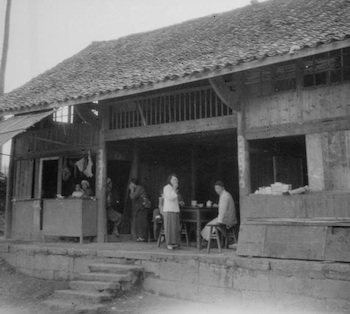

Fig.2 Billboard advertisement for a tea store, Shanghai, 1937 (Photograph: Harrison Forman. From the American Geographical Society Library, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries.)

Teahouses also accommodated clients' habits. Bird lovers could bring their cages to hang under the eaves. Water pipe smokers could have teahouse waiters affix shredded tobacco to their pipes. Folk music lovers could enjoy the house entertainment and sometimes even participate and perform for their peers (Interview 1). Some of Nantong's regular teahouse patrons would visit their favorite teahouse first thing in the morning to wash their faces, since warm water was not always available at home. Hot water and towels were a teahouse staple for regular customers (Interview 1).

Nantong teahouses started their business at about five o'clock in the morning, serving tea until noon. 'Pure teahouses' usually closed before noon and reopened in the afternoon for entertainment. Tiger stove teahouses supplied warm water all day, sometimes even at night, providing tea at any time since it was rather convenient to do so. Teahouses did not have evening hours; indeed, there was little nightlife of any kind in Nantong before 1917. The pattern of this small town's nightlife changed in 1917 with the introduction of electricity, and consequently electric streetlights. The streetlights did not exactly 'turn night into day' or 'disenchant' the night (Schivelbusch 1988, 3, 133-34, 153-54). However, they did enrich night life in tangible ways: local theaters began to stage regular evening shows; grocery stores, stationery shops, and restaurants all extended their business hours after dark, some until midnight, hoping theater-goers would pay them a visit after the evening performance. Some teahouses now remained open into the night for entertainment—though not for offering tea; the custom was that no tea would be served after dinner (Interview 1).

Entertainment, mainly storytelling and folk music, was another major attraction of teahouses. Nantong did not have specialized story halls at this time. Storytelling usually took place in pure teahouses in the afternoon and evening. There were at least ten such pure teahouses in Nantong city that also served as story halls. Most storytellers were invited from out of town by teahouse owners. Often they would perform over a period of ten or twenty days (Xu 1992, 34-36). Such events would be advertised with brief informal notes posted at the entrances of city streets, lanes, and alleys, similar to the way other official and public announcements were posted. Afternoon and evening patrons, consisting mostly of local residents, were not as diverse as the morning customers. Children were allowed to attend teahouse storytelling with their fathers. Members of the audience often participated actively in the storytelling process, for most stories were based on Chinese popular fiction and were thus familiar to the audience. Once, a storyteller in Nantong made a mistake about a detail in The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, and the teahouse audience detected it immediately. Some patrons took offense and ordered the storyteller to get off his table, demanding to know, 'Have you read the story before coming here to tell it?' In the end, the teahouse owner had to apologize to the audience and promise them a special treat the following day. The storyteller, after 'falling from the table' (daotai), was never again invited to Nantong (Interview 5). Thus, teahouses not only entertained their customers but also provided them with an opportunity to amuse each other, to show off, and to gain a sense of personal efficacy, perhaps to compensate for the feeling of powerlessness in everyday life.

However, teahouses were not merely places of leisure; they were working spaces as well. The popular notion that a teahouse was a leisure locus needs to be re-examined. Admittedly, many people went there for relaxation, and some teahouses were more leisure-oriented than others; but teahouses also served as 'offices' for various tradesmen. For instance, teahouses were ideal places for business meetings. In Nantong city, the teahouses on Eastern Street, where small shops concentrated, were frequented by shop owners, retailers, and their partners for business dealings, while their homes were usually too small for such activities. The busiest time of day for teahouses outside the Southern Gate, where there was a big market, was after ten o'clock in the morning. By then the market fair was over, and merchants, pedlars, and peasants came to the teahouses to rest and also to negotiate and arrange business for the next day. While using the teahouses to their advantage, those small merchants contributed to the flourishing of the local teahouse. Teahouses also served as 'offices' for litigation and other brokers, as well as for policemen gathering information. That is why they were sometimes identified by such functional terms as 'jiangcha' ('talk tea' -informal mediation of disputes), 'dingwu shichang' (real estate market), and 'baodating chahui' (inquiry teaparty) (Yu 1987, 214). In some cases, the name and location of teahouses not only indicated their character as working spaces, but also the kind of business they conducted. In the late-Qing dynasty, two teahouses were located on the eastern and western sides of the Haimen County yamen respectively. Both teahouses served as informal offices for litigators. The one on the east was named Dongsheng Yuan (Eastern Winning Garden), while the one on the west was called Xisheng Yuan (Western Winning Garden). The names implied that whoever conducted their lawsuits in these teahouses would win; the lure of self-interest was thus used to attract customers (Chen 1992, 29).

One litigation broker who frequented the Eastern Winning Garden was Liu Erbao. From an impoverished gentry family, he needed clients to support his family of five. In order to attract them, he pretended he was wealthy, hiring as his personal servant a seasoned actor named Lao Liu. Whenever peasants would approach Liu Erbao, his 'servant' would appear and bow to him: 'Mr. Er, an old duck has been steamed tenderly at home and you must eat it right away.' Liu would slowly get up and pretentiously respond: 'Yes, Mr. Er is coming.' Affecting he was in such high demand that he could afford to attend to a duck before taking care of his business, Liu would tell his client: 'This master (Laoye—himself) has to go home for a meal; please wait' (Chen 1992, 30). In this case, Liu Erbao used the teahouse as a theater to stage social drama aimed at making a living; the teahouse, in turn, did good business with regular customers such as Liu and his clients.

In some cases, it is doubtful if leisure alone could have sustained the teahouse. There was a teahouse near the front gate of the Tong prefectural yamen, where the Qing prefectural court was located. After the Manchu's fall, its business declined when lawsuits began to be handled by the county court, situated in an old temple south of the former yamen. Subsequently, a teahouse sprang up in the vicinity of the new courthouse (Ji, 1989). Recognizing the multiple purposes of teahouse-goers, Fan Shuzhi argued that those who came to teahouses were producers (shengchanzhe) instead of consumers (xiaofeizhe) (1990, 279). While the term 'producer' in this context may require some qualification, Fan's point is that some teahouse-goers primarily engaged in business dealings while consuming tea, rather than merely enjoying leisure.

A popular gathering place favored by practitioners of various kinds, teahouses came to reflect new tensions in career dislocation and competition. Such tensions, for example, were visible in the legal domain, where traditional litigation brokers were challenged by new developments in the early Republic, including the rise of professional lawyers.

Litigation brokers had long been active in local society in imperial China. They played a vital role in informal justice by writing plaints for and advising litigants (Macauley 1994). Social change in the late-Qing and early Republican period significantly affected this group. For one thing, their number increased toward the end of the Qing (Chang 1994, 316), due in part to institutional changes and consequent career dislocation. For instance, the abolition of the civil service examination system left many private tutors without jobs. Alternative opportunities were available, but they often required updated education and training. The transition for many was not easy. One tutor in Nantong first tried to get himself elected to the local assembly after his private academy was closed; when that failed, he became a litigation broker (Xinbao 25 July 1917, 7). Also, while low-level government students such as shengyuan still comprised a segment of litigation brokers (Chang 1994, 314- 15), litigators became increasingly diverse in their composition. In Nantong, they now included teahouse operators, gangsters, policemen, legal clerks, as well as local street hustlers (Xinbao 2 November 1917, 6; 20 December 1917, 7; Chen 1992, 29).[20] As Chang pointed out, formal legal training in Qing China was not necessary even for those who worked within the legal system, and customary rules embedded within a particular culture and the operational rules of local government were often as important as the formal legal code (1994, 298-303, 308-9). Therefore, it did not take academic degrees and expertise to become a litigation broker. What was more important was one's social finesse and 'people skills,' including the ability to manipulate and maneuver. With more and more people of varied backgrounds joining the ranks of the litigation brokers, competition among them became fierce.

What was perhaps most challenging for the litigation brokers, however, was the emergence of the professional lawyer. Compared with the traditional brokers, new lawyers held a commanding advantage. Most had received a formal law degree, which was well respected. They also had fixed offices, telephones, and secretaries. They could afford to advertise their business in newspapers. More importantly, Republican law recognized professional lawyers and allowed them to represent their clients in court (Conner 1994, 217), but litigation brokers, as in the imperial past, were denied such privileged access. Often coming from well-to-do families and closely connected to the local power circle, the new lawyers also played an important political and civic role in the community. In Nantong, the first formal law office appeared in 1913. By 1919 there were more than ten such offices. One of the professional lawyers, Xi Genqu, a former county magistrate from a prominent gentry family, held both a juren degree and a law degree from Japan. After 1911, he was a member of the Nantong Police Bureau and a director of the Board of the Nantong Local Self-government Association (Fan 1964: 14/ 3a, 15/4b, 16/5a). Xi had ties with local elites such as Zhang Jian. He set up law offices in Nantong city as well as in Suzhou, Nanjing, and Shanghai (Xinbao 20 August 1917, 1). Xi's influence, derived from his education, economic status, and political background, was something with which the ordinary litigation brokers could not compete.

The teahouse was one of the arenas where tension in the legal domain was acted out. Liu Erbao, the litigator mentioned above, once tried to settle a case for a client outside the court with a certified lawyer named Lü Yangshan. Liu rejected the idea and won the case in the end. The story, however, did not end there. Having lost face, Liu sought revenge. He used the Eastern Winning Garden teahouse and his 'servant,' Lao Liu, to gather information about Lü's whereabouts. One day when Lü was passing the teahouse, Liu threw a bag of excrement in Lü's face, publicly humiliating him. Liu Erbao gained great notoriety as a bully because of this incident, scorned by some, feared by some, and admired by others (Chen 1992, 30).

Clearly, Nantong teahouses were multifaceted public institutions. They meant different things to different people. In times of rapid social change, teahouses mirrored the struggle among ordinary people and between competing social forces. Thus, teahouse culture could be a potentially subversive energy. On the other hand, however, the relative openness and informality of teahouse culture served soothing psychological and sociological purposes, for it allowed ordinary folk to release destructive emotions and cope with social change. It was thus part of what C.W.E. Bigsby called the 'adjustment syndrome' in popular culture-by helping the individual deal with his society, popular culture facilitates social stability (1976, 5).

The Trouble with Teahouses

Unfortunately, the dualistic nature of teahouse culture often went unrecognized. In the case of Nantong, what seems ironic is that while the flourishing of local teahouses was a by-product of the high-speed commercial and modern development in the region, the teahouses themselves and their culture were never embraced by the emergent cultural elites of the early Republic. In fact, the new cultural elites considered teahouses part of the vanishing past, a negative influence on the new, Republican age. Such a critical view was especially obvious in the pages of the leading Nantong newspaper, where the new elites leveled a sharp attack against teahouse culture. To understand this elite group and its intellectual and moral universe, as well as the environment that gave rise to it, we turn first to the local newspaper, Tonghai xinbao (Nantong and Haimen [counties] New Newspaper—hereafter Xinbao). Though not the first local newspaper, Xinbao was the longest lasting and best preserved.[21] It was published almost continuously for sixteen years, from 1913 to 1929.[22] Its principal owner, Chen Shen, was originally a village landlord. He earned secondary elite status at the county level by engaging in public works and associating with Zhang Cha, Zhang Jian's brother. To polish his image as a new elite and to expand his political influence, Chen started Xinbao with a Nantong man named Lin and two friends from nearby Haimen County, Liu and Zhang.[23] Not well educated, Chen left the paper's day-to-day operation to its chief editor, a Haimen native named Liu Wei. Initially, Liu hired a few assistants and some local reporters in Nantong and Haimen counties. Later, when the newspaper expanded to cover a greater part of the Jiangbei region, he employed additional staff in Rugao, Taixing, and Chongming counties as well. The newspaper started with two pages printed every other day, but soon the number of pages expanded to eight. Its three to four hundred subscribers consisted mainly of local schools, government offices, professional institutions, and large shops and stores. It became a daily newspaper in March 1924, with an increased circulation of almost one thousand (Guan 1983, 17-20; Guan 1993, 36-37).

Like many of his intellectual contemporaries, editor Liu Wei received his initial education in the classical tradition. Later he traveled to Beijing and other cities, experiencing first-hand the rising tide of modern culture that was to characterize the May Fourth era (Guan 1983, 19). But the people of Nantong did not necessarily have to travel to encounter the new and modern, for the new developments were taking place in their hometown. In fact, outsiders came to Nantong to witness its unusual modern establishments, which were most pronounced in Nantong city's new schools and offices, Western-style buildings, newly paved streets, and modern artifacts such as automobiles and mechanical clocks. With Zhang Jian's successful promotion of the 'model' image of Nantong, many intellectual notables of the day, including Liang Qichao, Huang Yanpei, and John Dewey, came to visit and make speeches (Shao 1997). Their presence was a novel source of excitement and stimulation to the locals. They exposed the people of the Nantong area, especially the educated ones, to the fresh air of the outside world, helping to breed modern, cosmopolitan minds in this hitherto small, provincial town. Furthermore, in order to make the ordinary folk of Nantong fit into the image of 'model' county residents, Zhang Jian in the late 1910s initiated a new theater program to reform local culture and people, which involved the renowned May Fourth theater reformist Ouyang Yuqian, as detailed below. All of this further put the locals in touch with new cultural trends of the time.

While Zhang Jian himself was primarily an economic modernizer with a conservative political and intellectual outlook, the modern projects he started nevertheless facilitated, much to Zhang's own dismay, the rise of new, radical thinking in Nantong.[24] It is little wonder, therefore, that new cultural elites like Liu Wei and his editorial staff emerged during this period. The term 'new cultural elite' here refers to a segment of the May Fourth intellectuals who created an aura of social prestige for themselves mainly by producing and transmitting fashionable cultural concepts and practices, which early-twentieth-century China craved. Unlike people such as Zhang Jian who were propertied and more established social and political elites, intellectuals such as Liu Wei were short on economic resources and long on ideas, which often served as initial 'capital' for them to gain social influence. On the other hand, like Zhang Jian and his peers, these cultural elites were a hybrid group- they themselves had not left the 'decadent' past too far behind.[25] But they distinguished themselves from the former by constructing a radical outlook, considering Chinese tradition inherently evil and imported Western ideas infinitely better. They were extremely self-conscious of being crusaders against tradition and pursuers of enlightenment. Xinbao provided a forum for them to shape this elevated self-image.

In studying the rise of modern culture in eighteenth-century England, J.H. Plumb showed how, among other things, this culture was expressed in the acceptance of change and a vision of the future, a desire for expanding knowledge and self- improvement, an appetite for the fashionable, and a pursuit of organized activities and professionalization. Such tendencies prevailed among the bourgeois middle class (1973, 3, 12, 17; 1982, 316-29). While early-twentieth-century China was different in many ways from eighteenth-century England, elements of the modern culture Plumb described were nevertheless evident among the new cultural elites of Nantong, as reflected in the pages of Xinbao.

The paper's mission was stated in its inaugural issue (18 March 1913):

The establishment of the Republic should be attributed first to the power and influence of newspapers. In the future it will also depend on newspapers to check local politics and reform social customs. That is why Chen, Lin, Liu, and Zhang have founded Tong-Hai Xinbao.

Clearly, the newspaper hailed the Republic as a change for the better and arrogated to itself an active role in the reformation of local politics and culture, thus positioning itself as a voice of modernity. Indeed, the pull of the new, modern, and Western and the push of Chinese tradition went hand-in-hand as a distinguishing feature of the May Fourth culture (Lee 1987, 500). The new elites' passion for the new era permitted them little tolerance for what they considered tradition, even in the use of language. For example, in 1918 a Xinbao reporter witnessed an argument in a teahouse between a local policeman and a group of peasants. At one point the policeman struck the table and shouted: 'How could we yamen let it go?' The reporter, ignoring the substance of the argument, emphasized in his story the use of the term 'yamen,' commenting that 'The term yamen is outmoded and the policeman used it to scare the ignorant peasants' (27 October 1918, 7).

Self-improvement and productivity were other virtues favored by the new elites of Nantong. On the surface, these virtues were part of Confucian tradition. But what was considered self-improvement had changed in the early twentieth century. Going to school, for instance, was regarded in the past as a means to refine oneself. But now only going to Western-style schools was favored; attending private academies (sishu) was belittled and criticized. In fact, private academies and teahouses were among the targets of Xinbao's most frequent attacks on 'decadent' institutions. Furthermore, self-improvement was no longer only an expectation of the elite class, but of the Chinese people at large. Such change was in part due to the popularity of Liang Qichao's concept of xinmin ('new citizenry')—a strong China depending on the successful renovation of the entire Chinese population. Yet another preferred virtue was professionalism, manifested in part in Xinbao's applause for the regular, professional education offered in Nantong's Western-style schools. The paper reported on school activities with great enthusiasm, highly praising those who contributed to the new educational institution (Xinbao 9 May 1918, 3; 17 May 1918, 3; 28 September 1918, 6; 16 October 1918, 6).[26]

By promoting certain aspects of community life and criticizing others, the newspaper was trying to define a new social order and cultivate a new set of norms in the name of the Republic. Such norms valued fresh experiences, formal education, professionalism, and a productive way of living. Such things were seen as part and parcel of the modern culture. It was within this cultural frame that Xinbao found fault with the local teahouses.

To be sure, as the site and object of multiple cultural representations, the teahouse and its culture had been variably interpreted and certain of its elements had been criticized prior to the Republic. The image of teahouses as dens of iniquity was not exactly new (Suzuki 1982, 535; Yan 1997, 19). But the early Republican new elites deliberately emphasized this one view from the past in ways that suited their own purposes and attitudes. Indeed, Xinbao portrayed the teahouse as an institution entirely poisonous to the Republican order. In the four years of Xinbao surveyed in connection with this study (1913, 1914, 1917, and 1918), upwards of 90 percent of teahouse-related reportage was highly negative,[27] giving the impression that teahouses were responsible for decadent people who idled their lives away or, even worse, for 'unruly' characters who engaged in indecent and unlawful activities.

Xinbao generally considered teahouses a social ill associated with the past. With the development of modern schools and factories and the establishment of a modern concept of time, the rhythm and norms of life in Nantong were undergoing redefinition (Shao 1997, 114-24). In the self-conscious moral universe of the new cultural elites, a 'normal' pattern of life meant going to work or school in the morning and coming home in the evening; being educated and productive in a formal, organized fashion. In such a world, leisure for leisure's sake was not accepted. Teahouses were seen as part of the non-productive floating world; customers were deemed incapable of finding respectable positions in the formal social fabric. Similar to the reformers of early modern Europe who considered pastimes a 'loss of time' and idleness a sin or an occasion of sin (Burke 1995, 143), Nantong's cultural elites referred to teahouse-goers as 'wastrels' (langdangzi) who led abnormal lives (Xinbao 15 April 1913, 2).

The passivity and non-productivity of teahouses were not the only, or perhaps even the major, problems that worried Nantong's new cultural elites. It was their perceived destructiveness—their contribution to moral decay and social disorder—that the newspaper found most disturbing. Social life in teahouses was relatively intimate, informal, and open. While these characteristics were exactly what attracted clients, they also raised concerns about order and social control. The mixture of lower class customers and the various activities permitted by teahouses—including prostitution, gambling, and the singing of obscene songs—conveyed a sense of moral laxity and promiscuity. Teahouses in small, out-of-the-way lanes and alleys were automatically assumed to be indecent; it was said that teahouse owners and customers purposely chose such locations to engage in unlawful activities and to avoid policemen. Indeed, teahouse sociability was peremptorily dismissed by Xinbao as a cover for immoral or criminal conduct (26 April 1917, 7; 5 September 1917, 6).

Brothels were licensed in Nantong; only unregistered, underground prostitutes (sichang) were outlawed. The prostitutes who worked in teahouses were often of the latter type. Xinbao printed stories about the disruptive effects of prostitution in teahouses. In one incident, policemen broke into a teahouse to catch prostitutes. Of the fifteen men and women involved, some escaped, while others were injured. In the melee, blood was spilled and teapots shattered (Xinbao 4 April 1917, 7).

Gambling was another vice purportedly sanctioned in teahouses. There were two kinds of gambling. The legal type was called 'civilized style' (wen shiyang), and usually involved four people playing cards or mahjongg. The illegal type, termed 'violent style' (wu shiyang), referred to shooting dice, which often drew a big crowd (personal communication, 21 June 1997). This was a popular pastime in Nantong teahouses, made less risky for owners and patrons alike because of protection—and active participation—by corrupt local police officers. Some policemen teamed with teahouse bosses to lure gamblers inside, and then shared a percentage of the take as a commission (Xinbao 10 April 10 1917, 7); others took a regular monthly bribe from teahouse owners in exchange for protection (Xinbao 4 April 1917, 7); still others were active gamblers themselves. There were incidents in which teahouse gamblers resisted arrest and beat up policemen (Xinbao 9 June 1917, 7). Though these reports were aimed at exposing corrupt policemen and gamblers, they nevertheless portrayed the teahouses as places that encouraged destructive, lawless practices.

Xinbao also targeted teahouse owners for their role in jiangcha. Far from the humble, timid character Wang Lifa in Lao She's Teahouse, who managed to keep his business alive through dramatic social upheavals by pleasing all his customers, teahouse operators in Nantong were reported to make profits by stirring up trouble in the form of jiangcha, one of the popular ways to deal with civil disputes outside the courts. As Fan Shuzhi has pointed out, because the teahouse occupied a special position as a locus of community life, it assumed a certain status as a legitimate center of mediation (1990, 280-81). The teahouse boss was a natural candidate for the role of mediator, though policemen, litigation brokers, and local know-it-alls also played that role. Jiangcha gave teahouse owners access to information, thereby enabling them to exert influence in community affairs. It also supplied customers. The minimum number of the people involved in a jiangcha case would be three: the two disputants and one mediator. Sometimes that number could increase to six or more, as, for example, when more than two parties were involved and each had a mediator.

According to Xinbao, some people started teahouses primarily for the purpose of jiangcha. One report alleged that Chen Yuancai of Juyang town 'opened a teahouse to extort money from people in the name of jiangcha.' Chen Rufeng and Chen Rujing were brothers who had quarreled over the division of their family property. They took the case to Chen Yuancai. For the first two sessions of jiangcha Chen Yuancai charged Chen Rufeng a fee of 6.40 yuan; the third time, Chen Yuancai teamed up with Chen Rujing to extort an additional jiangcha fee of three yuan from the hapless Chen Rufeng. The latter protested, bringing the case against Chen Yuancai to a town manager (xiangdong) (Xinbao 15 April 1913, 2). In this case, the dispute not only remained unresolved, but became further intensified, expanding to include the teahouse owner himself.

While arguably a scoundrel, Chen Yuancai seemed rather civilized compared with those who, according to Xinbao, resorted to force in jiangcha and turned their teahouses into a 'yamen.' In Xinkaigang town, a teahouse owner nicknamed 'Xu Zhenshoushi' (Town Commander Xu) was said to be extremely arbitrary and coercive. If anyone disobeyed him, he would not hesitate to use force. In one case it was alleged that when Cai Qigao disputed with fellow villager Du Xueli and came to 'Commander' Xu for justice, Xu immediately tied Du up and brought him to his teahouse, ordering him to pay four thousand wen to end the case. The matter took a turn for the worse when Du's wife, frightened by her husband's arrest, swallowed six boxes of matches in an attempt to commit suicide. Du learned the news and was anxious to go home, but Xu insisted on Du's signing an agreement to pay in exchange for his release. In the end, Du was forced to sign the paper (Xinbao 27 March 1917, 7). Xu's jiangcha almost cost the life of Du's wife. Another report indicated that a father tried to take over the land his son had inherited from his uncle. The son stole the title deed from his father and showed it to a local man of property named Wu Shiming. Wu grabbed the deed, refusing to return it until the son paid a fee of one yuan. The son then went to a local teahouse boss for help, who tied Wu up and asked for a jiangcha fee of six yuan (Xinbao 14 December 1917, 7).

In each of these reported cases, teahouse operators were described as conscienceless, peremptory, manipulative, or violent. The only thing they ostensibly cared about was profiting at others' expense. They used their teahouses as courts and resorted to unjust or illegal means to secure payment of arbitrary jiangcha fees. In none of these cases did the teahouse owners or their jiangcha actually help resolve a dispute. On the contrary, they invariably made matters worse: after a costly, stressful, and sometimes even life-threatening jiangcha, the dispute remained—or even escalated. Xinbao criticized jiangcha as a harmful old custom and teahouse operators as troublemakers.[28]

Litigation brokers who hung out in teahouses were another group cited by Xinbao as a telling example of a troubling teahouse culture. As mentioned earlier, social change in the early Republic had intensified the competition within and without the ranks of litigators. In addition, their public image was significantly damaged. In the imperial past, litigation brokers were perceived as protectors of weak peasants against oppressive officials (Macauley 1994, 95). In the early Republic, however, they themselves were considered extortionists of the poor. Historically, litigators in Nantong were called, among other terms, songshi (litigation master), caoxie songshi (straw sandal litigation master), and songgun (litigation trickster or pettifogger). Of these terms, 'songshi' in the past bore a certain degree of neutral or even positive connotation, while 'songgun' had definitely negative undertones. But now every mention of 'songshi' in the newspaper was about something undesirable, thus reducing the image of 'songshi' to that of 'songgun'. Xinbao also referred to litigation brokers as songpi (litigation ruffian), songtu (litigation fellow), and chi baishui zhe (those who drink 'white water'—meaning blackmail and extortion). When professional lawyers began to emerge and the term lüshi became popular, 'tu lüshi' (amateur lawyers) became another name for litigation brokers. All these terms were interchangeable, and the litigation brokers were stereotyped as 'tigers' and 'wolves'—predators all (Xinbao 20 June 1914, 4; Interview 5).

Many factors contributed to their tarnished image. The keen competition and the extreme means to which they sometimes resorted in order to survive, as in the case of Liu Erbao, was one such factor. Their varied, often questionable, backgrounds, as noted earlier, was another. But more importantly, it was the change in perception associated with the Republican era that led to the negative image of litigation brokers. If their practice in the past was a more or less accepted, customary rule, albeit a disturbing one to officials (Macauley 1994, 89-92), the new notion under the Republic connected that practice with the vanished empire and assumed that the establishment of the Republic had delegitimated it (Xinbao 20 June 1914, 4).

In fact, institutional change in the early Republic did incapacitate litigation brokers briefly. After 1911, the remnant local judicial organ (shenpan ting) and procuratorial organ (jiancha ting) of the late-Qing legal system were combined to become the 'Nantong Local Judicial Bureau' (Nantong difang shenpan ting), and the county magistrate was given full judicial authority (Li and Chen 1992, 54, 61; personal communication, 21 June 1997). It took some time for litigation brokers to adjust to this change; but they soon resumed their business, in some cases quite successfully (Xinbao 2 and 22 July 1914, 2), which took some people by surprise.[29] Thus, when the newspaper reported that litigation brokers continued to be active, it used the word 'still' to indicate something that was not supposed to be happening any longer (Xinbao 2 July 1914, 2).

Furthermore, litigation brokers were portrayed as opponents of the new order. In one report concerning the arrest of a litigation broker who had interfered with police work, it was stated that the defendant, Qiu Zhuyan, 'opposed the new government (fandui xinzheng) and undermined the public good (pohuai gongyi)' (Xinbao 21 October 1917, 7). Another report accused a 'litigation ruffian,' who brought an allegedly unwarranted lawsuit against a local school, of 'obstructing progress' (Xinbao 6 April 1917, 7). The report did not indicate what the man had done to hinder progress other than simply suing the school, which was, on the face of it, outrage enough, insofar as schools represented progress.

Professional lawyers, who often tried to distinguish themselves from traditional legal pettifoggers (Conner 1994, 223, 247), also helped to diminish the latter's reputation. New lawyers in Nantong claimed in their newspaper advertisements that they would serve justice in an impersonal and objective manner according to the law. They highlighted their academic degrees and their duly authorized licenses to practice law, conferred by the Republican government. They presented themselves as both the products and the guardians of the Republic (Xinbao 20 March 1913, 1). Though few in number, the new lawyers were among the rising urban elite class, not only because of their educational background and economic status, but also because of what they symbolized: formal education, professionalism, and the new Republican era. The litigation masters, on the other hand, were considered baggage from the past.

Little wonder, therefore, that Xinbao frequently exposed the alleged dirty tricks of the litigation masters. To be sure, the paper also revealed wrongdoings of certified lawyers.[30] But negative stories about professional lawyers were few in number compared with the routine exposure of litigation brokers. Xinbao reported that litigation brokers often gathered in teahouses to talk with local bullies about how to extort money and 'savagely oppress the people' (yurou banxing) (Xinbao 20 November 1917, 7). Some of the litigation brokers were said to visit teahouses with their private bodyguards, not so much to protect themselves as to threaten others when necessary (Xinbao 20 December 1917, 7). In fact, Xinbao criticized anyone who came into contact with litigators in teahouses. Shi, the police chief in Shigang town, was said to have had a good reputation. But once he was reported to have been seen in a teahouse talking with local litigation masters, his sense of duty was openly questioned (Xinbao 20 November 1917, 7). The reporter did not substantiate that what Shi and the others actually said or did was immoral or illegal. Shi's principal wrongdoing, it seems, was to have socialized with the litigators in a teahouse, which was enough to warrant a public exposure and warning.

Depicted as a notorious gathering point for undesirable elements in society—conniving litigation brokers, mean-spirited teahouse operators, corrupt police officers, wastrels, and gamblers—the teahouse was purged from the new cultural elite discourse as a legitimate public space. Xinbao reported that while 'foolish country folk' in Kouzheng town of Taixing County often went to teahouses to seek justice through jiangcha, the town's elites had no such 'evil habits'. When disputes arose among peasants, local elites would meet in private homes, temples, and 'all [other] public loci' (yiqie gonggong changsuo) to render their judgements—but not in teahouses (Xinbao 25 September 1917, 6). Implicit in all this was the idea that teahouses were not legitimately 'public' places.

In reality, teahouses, like temples, only more so, clearly were public spaces, both in their physical setting and in their social representation. Because of the prevailing negative image of teahouse culture conveyed by Xinbao, however, they could not be recognized as such. The concept 'gong' (public) carried an inherently positive connotation in Chinese political rhetoric. Ever since the Warring States period, 'publicness' had been rosily packaged along with an increasingly idealized elaboration of the ancient 'Three Dynasties'. The term 'gong' gained new meaning in the early Republic. Politically, it was employed to legitimate the new government in contrast to the fallen dynasty, which was symbolically owned by a private family. Socially and culturally, 'public' carried high values—the interest of China as a nation, calling for personal sacrifice in its defense—as opposed to the narrow concerns of self-interest and self-indulgence. 'Public' thus implied something politically progressive and morally superior. Measured by this standard, the teahouse was disqualified as anything remotely close to 'public'; indeed, it was totally dismissed from the public sphere as defined by the purveyors of the new culture.

Viewing the teahouse as an alien space and teahouse-goers as an unruly lot, Xinbao expressed considerable fear of the teahouse culture, and along with it, an urgent need to control it. The primary concern was ostensibly with the maintenance of social stability and moral decency. Reports on teahouse disorders often emphasized that if such behavior persisted, peace (an'ning) in the community and the welfare of the people would be sacrificed (Xinbao 27 March 1917, 7). Xinbao applauded those victims of teahouse violence who had the nerve to stand up for themselves. The newspaper frequently appealed to 'public justice' (gongdao), local authorities, and the formal legal system in the hope that measures would be taken to prevent and punish misconduct in teahouses. In other cases, the reporters would directly suggest that certain practices be banned, and those who caused disruption be disciplined (Xinbao 6 April 1917, 7; 16 October 1918, 7).

The pressure Xinbao tried to put on local authority and law enforcement agencies was obvious not only in its ruthless attack on police corruption and impotence, but also in its attempt to hold local officials accountable for teahouse violence (Xinbao 5 September 1917, 6). When teahouse conflict erupted into lawsuits that required court attention, reporters would openly speculate as to whether the county magistrate or other local responsible officials would be likely to handle the cases properly or would be deceived by teahouse 'bullies' (Xinbao 15 April 1913, 2; 27 September 1917, 7). Such reports revealed a certain anxiety as to whether the local government's authority in maintaining social order would be compromised or corrupted by the teahouse culture. That Xinbao kept a watchful eye on local officials in their relationship with teahouses is revealed in the following report:

Yesterday, the police chief Mr. Yang of Jinsha town [of Nantong County], dressed in full uniform, went to a teahouse with a town clerk, Zhang Yuan. That a responsible military officer and a servant sat together and talked intimately not only disgraced the officer himself but also embarrassed the other customers. I heard that it was because Yang and Zhang both frequented the same prostitute that the difference in their social status did not matter to them.

(12 October 1918, 7)

Yang's uniform seemed the key point of this story, for it symbolized his position as a public figure; because of this, his socializing with a clerk in a teahouse was viewed as a compromise of his public accountability. Yang responded by defending himself in a letter to the editor:

It never happened that I was dressed in full uniform and talked intimately with a servant in the teahouse. First, I did not go to the teahouse with Zhang. Zhang was already there when I arrived. Second, we did not engage in a conversation. He said hello and I had no reason not to respond. Besides, since we were having tea at the same place, why would social status matter? Also, talking to the next table does not mean the intermingling of high and low. This is to correct the previous report which was meant to destroy my reputation.

(Xinbao 16 October 1918, 7)

Yang's retort can be read in various ways. On the one hand, he understood that socializing with the lower orders in teahouses diminished his image, so he denied doing it. Downplaying his encounter with Zhang, he rejected the suggestion that it compromised the performance of his public duty. On the other hand, he tried to defend his behavior by appealing to popular image of teahouse culture that allowed normal status rules to be temporarily bent or broken. While Yang thus expressed ambivalent feelings toward the teahouse culture, Xinbao suggested that teahouse culture was itself inherently evil and that local officials must disengage themselves from it to regain public trust and personal dignity.

Xinbao's attack on teahouses undoubtedly represented, and in turn reinforced, a certain social bias against the institution and its culture, especially among its readers, which mainly consisted of students, teachers, theater activists, big store owners, and mid- to upper-level merchants, professionals, and government officials. In the 1910s and 1920s, students from well-to-do families would make a detour en route to school in order to avoid passing teahouses. Major shops and stores forbade their apprentices and trainees from going to teahouses. Anyone violating the rule could be dismissed. The assumption was that apprentices were supposed to save money and learn skills needed to make a living in the future, and that they should not be exposed to teahouse habitués who were presumed to have no proper occupations or to be engaged in dishonest trades (Interview 3).

However, Xinbao's influence was evidently confined to educated circles. Its criticism did not stop ordinary folk from visiting teahouses, nor did it seem to succeed in altering the local government's attitude toward teahouses, which was laissez-faire in nature. Notwithstanding all the negative publicity, the local government made no effort to regulate teahouses directly. Underground prostitution and 'violent' gambling were outlawed, of course; but this policy did not target teahouses in particular, since such practices occurred in other public or quasi-public places as well. Moreover, Xinbao never published follow-up reportage on those teahouse stories that were ongoing or unfinished.[31] Given the paper's eagerness to criticize teahouses, the lack of such follow-up reportage was unlikely to have been coincidental. In this connection, it appears that local government generally ignored such incidents altogether, maintaining instead the customary attitude of official non-interference in teahouse affairs.

This raises an intriguing question: if the teahouses were indeed as destructive of public morality and socio-political order as Xinbao suggested, why were they not banned or regulated by the local government? Here we have to turn from the moral world of the new cultural elites as opinion makers to the functional world of local political elites as policy makers and their discriminating attitude toward public places such as the teahouse.

Public Places, Social Graces

Fear of social disorder and moral decline has been a pervasive theme in urban and industrial development (Stedman-Jones 1971; Smith 1995; Haine 1996). In European history, the propertied classes tried to regulate the lower orders in their living conditions as well as in their leisure pursuits, especially when the latter were perceived as a threat to established authority. The policing of Paris cafés and the 'moralizing' of outcast London were two prominent examples of late-nineteenth-century urban regulation (Stedman-Jones 1971, 271-80; Haine 1996, 22-32). Typically, such efforts reflected concerns over the putative lower class propensity for collective violence and political disorder, as in the case of London's casual laborers (Stedman-Jones 1971, 281-300), or potential substance abuse leading to moral corruption and social disruption, as in the case of Parisian cafés (Haine 1996, 22-32). In both cases, when society at large was perceived to be in crisis, the need to control the lower classes was felt more urgently.

In early-twentieth-century Nantong, occasional incidents of violent popular protest did take place as a reaction to reform programs (Shao 1994, 192-97). Notwithstanding such stresses, however, Nantong remained generally stable. Zhang Jian's dominant position and his status as a national figure protected Nantong from warlord harassment from the outside. Within Nantong, institutions were established to care for the underprivileged (Shao 1994, 67-68). Various reform projects absorbed a great deal of energy and attracted the most talented and ambitious people in the community. Nantong's 'model' status evoked a sense of pride even among ordinary locals. Of course, not everyone was content; but the community as a whole was relatively secure. This security was not threatened by the existence or activities of teahouses; and the local government thus did not need to rigidly repress them to ensure order. No harm, no foul.

Moreover, teahouse violence was neither ubiquitous nor serious enough to call for urgent action by local authority. More than likely, Xinbao overstated the destructiveness of teahouses. To be sure, Xinbao did not invent the stories it reported. The problem is that the newspaper was interested only in stories of teahouse wrongdoing, thus spreading the impression that teahouses were uniformly evil and that violence there was out of control. As suggested earlier, there were socio-political factors that contributed to the dualistic nature of teahouse culture: it could be an unsettling force in society as well as a stabilizing one. However, Xinbao's stories completely overlooked the potentially positive impact of teahouse culture. In this connection, it should be noted that the newspaper covered a broad geographical area that included as many as one thousand teahouses. Among these, there were only thirty- five reported cases of disturbance in my four-year sample—a poor indicator that teahouses in the Nantong area were generally chaotic.

Also, as members of a new, 'progressive' cultural elite seeking to portray teahouses as sinister reminders of a perverse past, the newspaper's staff may have been too biased to recognize that teahouses were economic as well as social institutions. As such, they were subject to market forces. If they were indeed so uniformly violent, and their owners so uniformly mean-spirited, they would not have been able to attract and hold patrons. Even the hypercritical Xinbao once noted the existence of a 'decent' teahouse operator named Sun who was said to be understanding and fair. As a result of his good deeds, his business grew—a case of virtue rewarded (Xinbao 20 October 1918, 7). Though this was the only positive report on teahouses among the thirty-eight news items collected by the author, we may safely assume that Sun was not the only teahouse owner who understood the relationship between doing well and doing good. Moreover, as discussed earlier, some teahouse violence occurred in reaction to outside events. Sometimes teahouses owners had to stand up to local bullies to protect themselves or their fellow townsmen, thus causing confrontations. Teahouses themselves were not necessarily the root of all the problems that found expression there, as Xinbao led its readers to believe.

Putting aside Xinbao's exaggeration of teahouse disorders, the incidents reported by Xinbao bear two primary characteristics that minimized the government's concern. First, they were localized cases, scattered widely among individual teahouses and generally involving isolated individuals, thus limiting the overall social impact of such occurrences. This is not to suggest that the disturbances were insignificant or that the individuals involved did not constitute a distinctive social stratum. It is only to point out that violent episodes were not collective acts committed by organized groups. The dispersion and spontaneity of teahouse violence made it difficult to predict and control on the one hand, but also reduced the magnitude of its societal threat on the other. Secondly, violent incidents in teahouses were by and large apolitical. To be sure, as in the case of the European coffee house, the Chinese teahouse could serve as a forum for political groups to advance their own interests. Some teahouse activities, such as discussing local tax policies and criticizing corrupt county officials, did have political overtones. But teahouse violence did not constitute a direct challenge to local political authority. Most of the disputes were over civil matters. Although some of the litigation brokers who patronized teahouses were accused by Xinbao of opposing the government, no evidence was ever presented to substantiate such charges. The apolitical nature of teahouse disorders thus posed little challenge to the local government establishment, enabling it to adopt a more relaxed attitude.