|

FEATURES

Teahouse | China Heritage Quarterly

Teahouse 茶馆

Lao She's 老舍 Play and Ying Ruocheng's 英若诚 Performance

Ying Ruocheng and Claire Conceison

The novelist and playwright Lao She (Shu Qingchun 舒庆春, 1898-1966) accounted for a history of modern China, from the late Qing until the end of the Republic of China, by recounting the vicissitudes witnessed by a Beijing/Beiping teahouse, Yutai. In Lao She's time as a celebrated 'people's artist' in the years before the Cultural Revolution, the interdiction posted on the wall of his stage teahouse, 'Do Not Discuss Affairs of State' 莫谈国事, remained salient; they are as much of a warning today as they were during the embattled years of the past, be they pre- or post-1949.

The following material is reproduced from the autobiography of the actor Ying Ruocheng, written in collaboration with Claire Conceison, and published as Voices Carry: Behind Bars and Backstage during China's Revolution and Reform, Rowman & Littlefield, 2009.

Claire Conceison is a Professor of Theater Studies and Asian & Middle Eastern Studies at Duke University.

Capitalizing on the fame of the much-loved play a Lao She Teahouse, a tourist-oriented performance eatery, was opened in Beijing in 1988 (see here and here.). A film version of Lao She's stage play was made by Xie Tian 谢添 in 1982.—The Editor

Full House for Teahouse

Of all the productions I participated in as an actor, the most significant was Teahouse. It debuted in 1958, and the people of Beijing had never seen anything like it. At that time, a typical play might run for a week, and that was considered lucky, but Teahouse ran for over a hundred performances.[1] Beijingers continued attending plays after Teahouse opened in 1958, but by the early 1960s, it became very difficult to draw audiences to the theatre. Following the failure of the Great Leap Forward, the economy was very bad—a period we referred to by the euphemism 'the difficult years'.

After the early, heady days of the new republic, China's intellectuals embarked on a terrifying roller-coaster ride. Our leaders initially exhorted us to speak our minds during the 1957 Hundred Flowers Movement, but then, almost overnight, the leadership counter-attacked, and those who had made the most scathing comments were singled out and labeled 'Rightists'. During the nationwide movement, at least 300,000 people suffered this disgrace—my brother Ying Ruocong was one of them. Scientists, technicians, teachers, artists, and others who were targeted were demoted in rank, forbidden to practice their professions and sent to the countryside to do manual labor. Many of them, like my brother, were rehabilitated only after two decades or more.

Fig.1 Ying Ruocheng as Liu Mazi (Pockmark Liu) in Beijing People's Art Theater's 1958 production of Teahouse (Photograph: courtesy of Claire Conceison and Beijing People's Art Theater)

The whole affair shocked China's intellectuals and muzzled most of the malcontents. It also created the necessary political atmosphere for the next big movement—the Great Leap Forward. In 1958 peasants were told to double or triple their production quotas, with the theory that once certain ideological barriers could be breached, the working masses were capable of achieving miracles. The leaders realized the quotas were excessive, but it was an article of faith that the masses should never be doubted or discouraged. Soon the media caught up with this strategy, and in due course there were endless reports of miraculous harvests. Factories in the cities picked up on the fever and steel production quotas were doubled. The entire countryside was collectivized, with production teams upgraded to brigades and brigades transformed into people's communes, in which the collectives shared the work and its spoils. Family kitchens were abolished and everyone ate in communal canteens free of charge. It seemed that, overnight, China's problems were going to be solved.

Amid these glowing reports about the success of the Great Leap Forward, we in the theatre company were totally unaware of what was truly happening in the countryside. We went on blithely performing every evening and rehearsing new plays during the day. Then suddenly we noticed a surge of peasants on the streets of Beijing, some of them begging for food door-to-door. At first we thought this was due to natural disasters in isolated areas. But as the days went by, the number of what the newspapers called 'vagrants' showed no sign of abating. We knew something must have gone wrong. Edible goods began to disappear from grocery-store shelves, and the rules for buying grain products with ration coupons were strictly enforced.

It was now up to the state propaganda machine to explain away the food shortage, and each explanation was more bizarre than the last. No one dared state the truth. In Marxist jargon, it was a classic example of 'ultra-leftism' when leaders are divorced from reality, confusing it with wishful thinking. It was precisely the kind of thing Mao had opposed during the 1930s, but this time, Mao himself was the ultra-leftist.

During the three 'difficult years', my wife gave birth to our second child, Ying Da. He was born a healthy 3.6 kilograms, but I didn't know how we would be able to feed him. We were luckier than most of our colleagues, since we had a bit of extra money from my moonlighting as a translator. With those funds, I surreptitiously bought food on the black market. We managed to scrape by thanks to my wife, who spaced out the little food we had to make it last as long as possible. Not every family was so fortunate—many couples split up amidst the pressure brought by the shortages.[2]

Plays during that period became political propaganda, and people just got bored, but by 1962-1963, we began to draw people back to the theatre by reviving popular plays like Teahouse.[3] Then the Cultural Revolution began, and we no longer staged plays for the public at all.[4] Artists were shipped off to cadre schools in the countryside, while Wu Shiliang and I were sent to prison. After the Cultural Revolution finally ended, the theatre's most popular pieces were revived because the young people had never seen them. This brought audiences back to the theatre and artists back to the stage, and Teahouse in particular created a huge sensation.[5]

After Lao She's tragic suicide following his interrogation during the Cultural Revolution, the revival of his masterpiece was considered a spiritual triumph.[6] As an actor who had performed in many of his plays, I was elated to see him rediscovered and appreciated. When the new regime had been established in 1949, Lao She was already a well-known novelist, and through his close relationship with the Beijing People's Art Theatre, he developed into a dedicated playwright. He felt that the performing arts were more accessible to the common people than printed literature, which required literacy from readers. In his first collaboration with the theatre, on Dragon Beard Ditch, he found in Jiao Juyin the ideal stage director for his plays. Most of the actors in the brand new theatre company were in their twenties and inexperienced, but guided by Lao She's writing and Jiao Juyin's directing, they became the best interpreters of Lao She's work. Between its founding in 1950 and its staging of Teahouse in 1958, the Beijing People's Art Theatre produced more than half a dozen of Lao She's plays, including a stage adaptation of his famous novel Rickshaw Boy (also known as Camel Xiangzi), in which I played Liu Siye (Fourth Master Liu).[7]

Fig.2 Ying Ruocheng as Liu Mazi Jr. in the 1979 revival of Teahouse (Photograph: courtesy of Claire Conceison and Beijing People's Art Theater)

Teahouse came about in a rather interesting way. In the original version of Dragon Beard Ditch, there was a scene set in a small teahouse, and this scene became a favorite moment that instigated the idea of a separate play with a similar setting. Lao She was also deeply interested in the idea of constitutional democracy in China (something that had inspired his play A Family of Delegates). After the Constitution of the People's Republic of China was created in 1954, Lao She wrote another play about the history of constitutional democracy and its failure under all the regimes before 1949. When he came to the theatre to read his first draft, people were not very enthusiastic and he was prepared to scrap the whole thing. But everyone agreed that there was one scene set in a Beijing teahouse at the end of the nineteenth century that should be expanded into an entire play. The result was Teahouse.

The play has more than sixty characters and covers a span of fifty years, from 1898 to 1948, showing daily life in a teahouse during the fall of the Qing dynasty, the establishment of the Republic, and the civil war between the Nationalists and the Communists. Lao She's stage directions call for a sign to be plastered on the wall throughout the play that says 'Do Not Discuss Affairs of State'—a move that required quite some courage at the time. Unlike other plays of the time, Lao She never tackles any of the political issues of the day head-on, but provides convincing three-dimensional images of the common (and even the grotesque) that were rarely portrayed on stage up until then. Some of the play's most memorable scenes—such as an aging eunuch buying a young wife—verge on the bizarre and ridiculous, but simultaneously give the play a remarkable inner truth.

Lao She's mastery of Beijing dialect and the language of the man in the street—from coolie and shopkeeper to artisan and petty official—was unsurpassed, and made his work, especially Teahouse, almost untranslatable. In 1978, I accepted the challenge and produced an English translation that was published and used for British and other European audiences when we toured the production in 1980.[8]

Synopsis

The following synopsis of the play is taken from the promotional materials for the 2005 Kennedy Center Festival of China, at which the Beijing People's Art Theatre performed a revival of Teahouse:

The 'Yu Tai' teahouse in the ancient capital of Beijing was a witness and a microcosm of the times.

In the first Act, which takes place in the year 1898, the year of reform and the ensuing crackdown, we see the plight China has been reduced to: a weakened state, an impoverished populace, foreign aggression on the rise, foreign goods, including the infamous commodity, opium, flooding the market. The peasantry, mainstay of the nation, was forced into bankruptcy and selling off their own children. Residents in Beijing, as exemplified by frequenters of the teahouse, were apathetic to the national disastrous situation, but the discerning few, the better informed, began to get involved. Some advocated political reform, trying to persuade the reigning Emperor to head the movement; others pinned their hopes on industrialization as the only way to bring the nation to prosperity and the people to affluence. All these hopes were dashed after the crackdown. With the success of their coup, the die-hard ruling clique at the court was more arrogant than ever, even the Grand Eunuch insisted on the impossible, he wanted to by a young girl as his bride .The Imperial Secret police was more powerful than ever and the underworld barons had their heyday. All these, of course, leads to the inevitable conclusion: The Great Qing Empire is finished.

The Second Act takes us twenty years later. The Dynasty has fallen, a Republic has been set up, but the people are worse off than ever. In the same teahouse we see the manager trying his best to keep up with the times, but the incessant civil war waged by warlords of different factions and the general anarchy and lawlessness makes his efforts totally futile. In the distance, however, we begin to hear the rumble of a revolution, the younger generation, represented by the students, are restive and fomenting a protest under the banner of patriotism and democracy.

The Third Act takes us another thirty years later. After eight years of bitter war against the Japanese, the common people had hardly had time to celebrate China's victory when the reactionary factions in the Kuomingtang instigated an all out civil war. The political situation became even more oppressive and corrupt, and we see even in this usually backwater gathering place, the Yutai teahouse, the seething discontent of the populace and the more vehement protests of the students. The manager of the teahouse now a man of over seventy, whose only ambition in life has one for survival, is finally reduced to despair and ends his own life.

The playwright, Lao She, who has been honored with the title of People's Artist, (the only writer to be thus designated in the PRC) thus condemns and buries three crucial periods in China's recent history, and transpires his hopes and love for the new society of which he was an active and ardent participant.

In the original production and the subsequent revival and tours, I played the role of Pockmark Liu (Liu Mazi) in the first and second acts, and his son (Pockmark Liu Jr.) in the third act. Liu was the worst of the lot. There were retired musicians; there were sellers of cheap cigarettes; there were sellers of peanuts—but he was selling human flesh. He was a pimp who arranged temporary liaisons, and also sold young women as wives to the highest bidder.

I still remember vividly Lao She's reaction to my portrayal.

'You brought the play to life', he said. 'But some people wished you to be more villainous.'

Lao She was a man of great capacities, and what he didn't know was not worth knowing. We actors all loved him, because he was so magnanimous and full of all sorts of humor.

Director Xia Chun was entrusted with the job of starting the rehearsals in 1958, but he didn't really do very much. He kept at it for about three weeks, by the end of which everybody felt hopeless. Xia had no idea how to deal with this. The play is rather unusual to begin with, with so many characters and such vast time coverage. At the time, Jiao Juyin was not immediately given the job for political reasons—he was going through the Anti-Rightist thing. The decision to bring him in to the rehearsals had to be made from quite high up. At last, after twenty days of moping around with Xia Chun, Jiao was called in, and the whole scene changed. Xia Chun stayed on, of course—with the kind of social system we had at the time, he couldn't exactly be kicked out. We all had to pretend that he was the director, but nobody took him seriously.

Jiao, on the other hand, was just about the most erudite theatre scholar I have ever met, and an exceptional director. He had spent many years in France, had been a university professor, and had founded the Chinese Traditional Opera School, so in addition to working with so many superb spoken drama actors at the Beijing People's Art Theatre, Jiao also mentored the most famous Peking Opera actors in the country.[9]

When Jiao Juyin directed me in the role of Pockmark Liu, he often took me aside to work on aspects of my character. Liu has a whole philosophy behind him and felt totally justified in what he was doing. As an actor, it wasn't enough for me just to play a villain. That's what made playing the role so interesting.

My Return to the Theatre

If I had stayed one more year at the theatre, I wouldn't have had to move, because the Gang of Four collapsed in 1976. They were arrested and imprisoned, and the atmosphere began to change, but I chose to remain at the Foreign Languages Press for two more years.

Eventually, my return to the Beijing People's Art Theatre was prompted by the fact that the theatre was always coming to the press to 'borrow' me for various projects. Our editor-in-chief finally got fed up and said, 'You constantly come and try to borrow him. It's like the tiger borrowing the pig. I'll never see the pig again.'

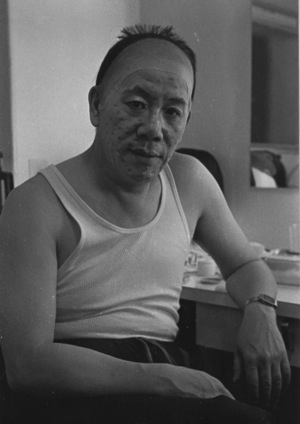

Fig.3 Ying Ruocheng backstage applying makeup to play Liu Mazi (Photograph: courtesy of Claire Conceison and Beijing People's Art Theater)

At the time, I did not wish to go back to the theatre. I thought that was a page in my history that had been turned for good. But several things happened that led me to change my mind. For one thing, there were a group of 'foreign experts' who were invited to China to assist with the editing of publications into foreign languages in China. These language 'experts' were unanimous in their praise for Lao She's Teahouse—the play was a phenomenon unto itself. Some of the foreign experts were long-time China hands who had seen Teahouse when it was first staged in 1958, and they enthusiastically recommended the play to other Westerners. I was persuaded by the Foreign Languages Press to translate it into English, which I did in 1978, and the play then enjoyed a second hit run in Beijing and was also well-received when it toured abroad. As soon as I finished the translation, it was published by the magazine Chinese Literature, a publication of the Foreign Languages Press.

Amidst this renewed interest in Teahouse, I was approached by the theatre. At that time Cao Yu was quite ill and Jiao Juyin had already passed away. I suddenly found myself one of the senior members of the theatre company. The administrators at the theatre all realized that without me it would be difficult—perhaps nearly impossible—to restore the play. I was one of the few people who could still remember the last time we produced it, which was in 1963, three years before the Cultural Revolution. Records hadn't been carefully kept and the notes weren't complete, or in some parts were even wrong.

So it was the revival of the play Teahouse in 1979 that brought me back to the People's Art Theatre for good. In addition to translating the script into English preceding the revival, I also reprised my role as Pockmark Liu. Teahouse became the first modern Chinese play ever sent to be performed abroad. In 1980, we toured Germany, France, and Switzerland. That same year, I accompanied our theatre president, Cao Yu, to England and the United States.

After Lao She's death in 1966, Teahouse became a prime target of calumny, and the amount of slanderous attacks on both the play and its production could fill a fair-sized volume. In that respect, Teahouse is but one of the numerous examples of good plays unjustly suppressed and banned during that period. Its rehabilitation and revival in 1979 helped people rediscover Lao She and reappraise some of the criteria by which Teahouse and other theatrical productions had been judged—or misjudged. As a literary critic phrased it during one of the symposia on Teahouse: 'We have not done sufficient justice to Lao She's writing in the past. It took the upheaval of the last ten to twelve years to make us realize that. There is much we can learn from Lao She.'

Having performed in many of Lao She's plays and in all performances of Teahouse from 1958 through 1979, I fully agreed with this assessment. Teahouse had always been a popular play and the audience reaction had always been strong—but we were not prepared for the rapt attention and outbursts of spontaneous laughter during the 1979 performances. Was it due to the nostalgia and goodwill of our old fans? Not entirely. For one thing, a large part of the 1979 audience consisted of young people under age thirty who had never seen any modern spoken drama, let alone Teahouse. The truth is that the revival of Teahouse served as a timely antidote to the kind of stereotyped ultra-Leftist fare crammed down people's throats in the previous ten to twelve years. For a large number of people to see life truthfully portrayed and to hear the everyday speech of Beijing turned into pithy, expressive dialogue were in themselves exciting experiences. Even more significant was the fact that after so many years of turmoil, people were beginning to realize that the evils of the old social order die very hard indeed and that the phenomena Lao She depicted in Teahouse as an indictment of past social injustices had reappeared in uncanny and devious ways. The result was that not only the audience but also the actors were reading new meanings into the text. Scenes like the arrest of Master Chang for worrying aloud about the future of the Qing Empire, or the illiterate thug being turned into a college student overnight in order to suppress student demonstrations, forcefully reminded people of what had been happening in their midst only a few years before.

In writing such incidents into the script, Lao She had been careful to heed his own warning that appears throughout the play in the form of signs plastered onto the walls of the teahouse: 'Do Not Discuss Affairs of State'. Lao She cleverly avoided specific references to politics, but merely depicted their impact on the lives of ordinary people during three periods (1898, 1918, and 1948) spanning fifty years—thereby creating a classic that remained as relevant in 1979 as it had been in 1958. It remains so today.

Source:

These excerpts are reproduced from Ying Ruocheng and Claire Conceison, Voices Carry: Behind Bars and Backstage during China's Revolution and Reform,

Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2009, pp.136-40 & 151-2. A Chinese version of the book was published as 水流云在:英若诚自传, Beijing: CITIC Press, 2009.

Notes:

[1] There were about fifty performances of Teahouse when it premièred in 1958 and another fifty when it was revived in April-September 1963. It was restaged twelve times during 1979-1981. For international performances of the place, see Note 8 below.

[2] Ying's recollection of the Anti-Rightist Movement and Great Leap Forward come from his article 'China's Wild Ride' in Time International.

[3] Archival statistics of the Beijing People's Art Theatre illustrate the startling accuracy of Ying Ruocheng's recollections: in 1957, audiences for plays (as determined by the length of the run of each play) increased from a previous average of less than or about one to two dozen performances to at least thirty and often upwards of fifty, sixty, or even seventy performances. Audience numbers peaked with 120 performances of Guo Moruo's Cai Wenji in May-December 1959, then began to fall again in 1960 and remained low until an increase in mid-late 1962. See Beijing Renmin Yishu Juyuan 1952-2002, pp.138-153.

[4] During the six years from June 1966 until September 1973, there were no spoken dramas created or performed publicly by the Beijing People's Art Theatre. There were, in fact, performances of a very limited number of political plays at the Beijing People's Art Theatre during the later years of the Cultural Revolution, but they were relatively few. From September-December 1973, three plays were performed there. In 1974, five plays were performed, three of them the same as in 1973. In 1975, the same group of plays was performed (with one addition) but with increased frequency. 1976 began with the same kind of repertoire, but activity picked up mid-year. All propaganda plays staged during the Cultural Revolution were collectively scripted works resembling huobaoju ('living newspaper plays'). For precise listings with full production information, see Beijing Renmin Yishu Juyuan 1952-2002, pp.153-160.

[5] Ying Ruocheng's reminiscences about Teahouse (both the 1958 original production and the 1979 revival) are drawn from two sources: our taped interview on 1 July 2000, and an article he wrote in English in 1979 ('Lao She and His Teahouse, pp.3-11).

[6] Lao She (Shu Qingchun, 1898-1966) drowned himself after being interrogated by Red Guards at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution. The revival of Teahouse in February 1979 with the original cast was ostensibly to commemorate the eightieth anniversary of his birth.

[7] The current Beijing People's Art Theatre's official founding date is 1952, though its establishment ('Old Renyi'), dates to 1950—which is when then-president Li Bozhao commissioned Lao She to write the play that would become Dragon Beard Ditch (Longxu gou). The play is listed in the theatre's official documents as premiering in 1953, though Ying Ruocheng correctly recollects that it was first staged in 1951, the year after Lao She wrote it. Plays Lao She wrote for the Beijing People's Art Theatre between 1950 and 1958 were Dragon Beard Ditch (written 1950, staged 1951 and 1953), A Family of Delegates (Yijia daibiao, written 1952, not staged), Spring Flowers, Autumn Fruits (Chunhua qiushi, 1953), Young Assault Troop (Qingnian tuji dui, 1956), Camel Xiangzi (Luotuo Xiangzi, original novel 1937, stage adaptation 1957), Teahouse (Chaguan, 1958) and Red Courtyard (Hong dayuan, 1958). Ying Ruocheng recalls Saleswomen (Nüdianyuan, or as Ying translates 'Girl Shop Assistants') as being produced before the premiere of Teahouse, but according to Beijing People's Art Theatre records, it was staged afterwards, in March-May 1959.

[8] Teahouse toured Europe between September and November 1980; visited Japan in 1983; played in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Canada in 1986; went to Taiwan in July 2004; and toured Washington, D.C., Berkeley, Pasadena, Houston, and New York in October-December 2005, marking the first time a professional spoken drama from China was ever performed in the United States. Ying Ruocheng's English translation was used for the supertitles during performances.

[9] Jiao Juyin (1905-1975) founded the school in 1930 and served as its president. In 1935, he enrolled at the Sorbonne in Paris, France where he earned a doctorate in 1938. He spent 1942-1946 in the wartime capital of Chongqing, then returned to Beijing and became the Dean of the Humanities College/Western Languages Department at Peking Normal University. In 1952, he was appointed vice-president of the Beijing People's Art Theatre (as one of its founding members). During the Cultural Revolution, he was sent to Heavenly River (Tiantanghe) cadre school for labor reform. He returned to Beijing and died of lung cancer in 1975, during the final year of the Cultural Revolution.

|