|

|||||||||||

|

FEATURESOn LiteratureOn 'Old Chinese Poetry'Chien Chung-shu 錢鍾書

This essay appeared in The China Critic, VI:50 (14 December 1933): 1206-1208.—The Editor

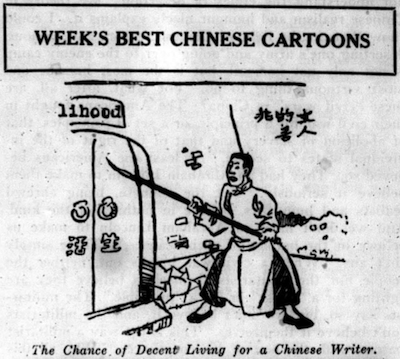

Related ArticlesMr Wu Mi 吳宓: A Scholar and a Gentleman, by Wen Yüan-ning 溫愿寧 Review of Edgar Snow's Living China (Modern Chinese Short Stories), by Sung I-chung 宋以忠 The Literary Magazines in Shanghai, by Henry H. Huang 黄聚韓 The Real Value of Chinese Literature, by Ngiam Tong-Fatt 嚴崇發 One of the consequences of 'The New Chinese Literature Movement' is the rupture between present-day literature and that which precedes it. Chinese literature is, as it were, chopped up into two—the old and the new. This rupture naturally brings about a complete transvaluation of old literary values. Here and there in contemporary criticisms of the old poetry, we are met with some vague cacklings about the Pacifism of Tu Fu (A.D. 712-770), the Socialism of Pei Chu-I (A.D. 772-846), the Radicalism of Yuen Mei (A.D. 1715-1797), etc., as if by the modernity of their—'isms' (all of which are duly honored with capital letters) were those old poets to be judged. We witness also a reversal in the literary fortunes of many men: Han Yu (A.D. 768-824), e.g., has to abide our question who has hitherto been above criticism, and a large host of old poets of varying shades of renown are now touched by the chill of neglect. These are but instances of the way the wind is blowing. Indeed, even the claim of 'Old' Chinese poetry as poetry has been seriously disputed in certain quarters. But the oft-made charges of formalism and artificiality against the 'Old' poetry are, to say the least, superficial. The 'defects' of 'Old' Chinese poetry do not lie in the rigidity of the Form (which, forsooth, is elastic enough), but in a peculiar sort of poverty in the Content. And I shall attempt to point out in this paper what we do not find in 'Old' Chinese poetry.  Fig.1 A parody of literary life: a writer beats on the door of 'livelihood' (shenghuo 生活), in The China Critic, 'Week's Best Chinese Cartoons', October 1930. Artist and origin unknown. The first thing that strikes a reader of 'Old' Chinese poetry is the comparative paucity of what Santanyana happily describes in his 'Interpretations of Poetry and Religion' as the Poetry of Barbarism. The most outstanding example is, of course, love-poetry. Amatory verses and songs on conjugal love we have, and in plenty. But for the poems that describe without any reserve that dynamic vital force which draws a man and a woman close together and that impact of hot feeling upon hot feeling, search where we will, we shall search in vain. Love is often treated as a domestic sentiment, something which suggests Mendelssohn's 'Wedding March', but rarely if ever as a primeval passion with untamed ferocity, that partakes more of the nature of a duel than that of a duet—witness the first poem in Book of Odes. The erotic 'Odes' describe lovers' clandestine meetings and flirtations rather than their raptures and deliriums. They are too soufflé in sentiment to become love-poetry worthy of the name. Great as Tu Fu is, love-poems are conspicuous by their absence in his works. Indeed, he seems to have written in blissful ignorance of the Heart. More gallant than Tu Fu, Li Po (A.D. 705-762) pays compliments to ladies some of whom are even technically 'undesirable', in many beautiful ditties. But, being of a mercurial temper, he regards woman as but a part of his joie de vivre; in fact, woman figures in his poetry mostly as his boon-companion. Li Shang-yin (A.D. 813-858),[1] the acknowledged master of Chinese amatory verse, sings of love-making rather than of love. The scenic setting of love-making furnishes a canvas for his consummate skill in poetical embroidery, and he accumulates on it learned imageries to achieve spectacular effects. All later writers of amatory verse follow suit. Suburban, domesticated scenes are invariably preferred to wild romantic ones; 'love in a valley' seems uncongenial to Li Shang-yin as well as to all later poets, and love in a boudoir would be infinitely more to their taste. The following description is very bald and unadorned for one from the pen of Li Shang-yin, but it gives the reader an idea of the typical rendezvous in Chinese poetry:

Li Shang-yin will tell the reader how the beloved shielded her face behind a moon-shaped fan to conceal her confusions at the sight of him, how she passed by him in a lumbering coach without so much as exchanging a word with him, how he was nervously startled out of his sweet dreams, how he hurried in writing his love-letters,[3] and thousand and one other little incidents which make love-making a pleasant idleness to the busy and a pleasant business to the idle; but about his own feelings he is nebulously vague, and the imaginative reader has to dot the i's for himself. Of course, it is 'bad form' to blow one's cheeks out with hysterical declarations of one's love, and Li Shang-yin's vagueness may testify to a perfect mastery of that art of 'suggestions' which Professor Herbert A. Giles gives so many Chinese poets credit for, but surely passion can not have our poet tightly in its grip, if he shows such self-restraint and insouciance. Even when he does touch upon love, pure and simple, he still employs what Aristotle calls 'indirect expressions':

So the reader is given to understanding that he (the poet) will love on to the end of his life. Li Shang-yin's way of dilating upon the 'adventitious' and leaving out the essential becomes the tradition in Chinese amatory verse. And later poets also use indirect expressions to a very great extent in order to conceal their emotions—sometimes their lack of them. One notices also that most of Chinese amatory verse is reminiscent in tone—'Emotion recollected in tranquility'. The poets all seem in their distant youth to have loved and lost,

This fact explains a good deal: When the poet gains tranquility and resignation, his passion necessarily loses ripple and edge. 'Affective memory' is psychologically an impossible feat: distant youth cannot be whistled back, and old glamours can not be recaptured. Moreover, there is in most of these verses a note of condescension on the part of the poet. The loved one seems to have won his love at the expense of her respectability and the poet seems to be aware of the fact and tries to make capital of it. This is perhaps due to the inequality of sexes in ancient China. And I venture to think that while the inequality of sexes cannot account for the absence of high comedy in the East—pace Meredith, it does partly explain the lack of genuine love-poetry in Chinese literature. The Chinese convention against calling a spade a spade has also a lot to answer for the metaphorical treatment of the theme of love. The time-honored definition of poetry (Sh'ih) as restraint or discipline (Ch'ih) clinches the matter. This definition is no mere verbal jingling; it somehow reminds us of Arnold's dictum that poetry is the criticism of life. As the ideal life of Chinese is one of decorum and ceremonious urbanity, discipline or restraint is an indispensable means to the end. Poetry thus acquires a pedagogic function, and becomes more or less a kind of 'responsible propaganda', to alter Mr Montgomery Belgion's useful terminology.[5] Accordingly, emotions raw, tempestuous and of a good 'body' (as we say of wine) must be subjected to a rigorous discipline—broken in, toned-down, lulled to a windless calm and diluted to a milky mildness before they are thought fit for expression.[6] The second thing a reader fails to find in 'Old' Chinese literature is meditative or philosophical poetry. Our didactic poetry is largely of the order of 'kitchen maxims', unredeemed by any ethical aspirations. Our old poets do not attempt to scale speculative heights or grapple with Life's problems—at least not in their capacity as poets. No sooner a poet philosophises than he becomes skeptical and nihilistic—witness the fusillade of questions shot at the T'ien (Heaven) in the third book of Chu Yuan's Li Sao. This lack of meditative or philosophical poetry becomes most conspicuous in piety dealing with Nature. Western poets are interested in Nature because she speaks to the spirit of man. They wonder at her beauty as well as exult in her significance. Whether they receive from Nature but what they give, or, as Professor Whitehead says in a highly suggestive passage in his Science and the Modern World, they express only the concrete facts of our apprehension which are distorted in scientific analysis, they are at least not merely 'sight-seeing'. Chinese poets, however, all regard natural 'views' as simply so many landscapes with an appeal to the sense of the picturesque. They are too unsophisticated or 'extravertic' to 'turn away from actuality', to borrow Mr Lascelles Abercrombie's phrase in his lecture on 'Romanticism'.'They will occasionally indulge in little passing moods; but their sorrows and joys are too volatile to crystallize into spiritual outlooks. Chinese Nature poetry is more remarkable for its sight that for its insight, for the finesse and minutiae in the description than for anything transcending passive observation. Hence the absurdity of drawing a Plutarchian parallel between T'ao Yuan-ming (A.D. 365-427) and Wordsworth. T'ao Yuan-ming's easy-going disposition totally unfits him for quasi-mystic broodings. To him (as indeed to all Chinese poets) Nature is but a background for hobnobbings and strollings. The solitary pine-tree and the chrysanthemums do not give him moments of spiritual consecration as the daffodils and the primroses do Wordsworth. If Nature inspires in him any desire to preach, he preaches what he practises—contentment and enjoyment: 'Ah, how short a time it is that we are here! Why then not set our hearts at rest, ceasing to trouble whether we remain or go? What boots it to wear out the soul with anxious thoughts? Thus will I work out my allotted span, content with the appointments of Fate, my spirit free from care.'[7] Or, as he says more boisterously elsewhere: 'Enjoy today to the utmost; let tomorrow go hang.'[8] We come across the same sentiment everywhere in Chinese Nature poetry. Two quotations from Tu Fu will suffice. After a detailed description of Nature's various manifestations in Spring-time, he winds up thus:

Again:

These quotations give the keynote to the whole Chinese temperament, a temperament not of contemplation but of enjoyment. This temperament, never surrendering itself to any contemplation for its own sake, makes it manifest not only in the lack of meditative poetry in Chinese literature, but also in the backwardness of pure science and 'puristic' philosophy in Chinese civilization. Both science and philosophy in China have been closely bound up and shot through with human interests, and neither gets to the stage when it becomes ethically neutral and ale to study things not sub specie humanitatis but sub specie aeternitatis.[10] In 'Letters from John Chinaman' there is a beautiful passage on Chinese literature: 'A rose in a moonlit garden, the shadows of trees on the turf, the pathos of life and death, the long embrace, the hand stretched out in vain, the moment that glides forever away with its freight of music and light into the shadow and mist of the haunted past, all that we have, all that eludes, the bird on the wind, a perfume escapes on the gale—to all these things we are trained to respond, and the response is what is called Literature.' But the question is: how do we respond? To us—to our old poets, at least—a rose in a moonlit garden is there simply to feast the eye—not to be 'understood, root and all' like 'the flower in the crannied wall'. The brevity of life makes the enjoyment of pleasures more imperative; the evanescence of pleasures renders the enjoyment of them more poignant. Whether the poet be hilarious like Li Po or quietistic like T'ao Yuan-ming in his enjoyment, he is not perverse in his pleasures or relentless in his pursuit of them. He will have nothing of that painful cult called Hedonism. He may be dissipated, if you please, but decadent he is not: there is a large healthiness even in his abandonments. Of course life is not a perpetual May-day with him; time and again the note of sadness is heard in his poetry. But this sadness is delimited to particular untoward events, and never diffused or universalized into an all-embracing Weltschmerz.[11] His attitude towards personal immortality is particularly illustrative. His is the biological in contradistinction to the spiritual standpoint; he concerns himself not with those abstruse problems of the imperishable soul, 'the faith that looks thru death', 'the deserts of eternity' which may lie beyond, etc., but with the prolongation of his own life to infinity. Endlessness of the present life rather than timelessness of the future one, persistence through time rather than transcendence of it, is his cherished aim—see, e.g. the series of poems entitled 'Sentiments and Moods' by Yuan Chi (A.D. 210-263), especially X, XXII, XXIII, XXIV, XXXV, XL, and LXXVIII. It follows that our old poets are incapable of that mysticism which modern critics attribute to them. Their temper revolts against any such dogged straining after the ineffable union of subject and object. Li Po, e.g., on whom epithets like 'mystic,' 'romantic' have been laid on thick, is a myth-maker, not a mystic poet. He records his happy wanderings in the realm of free fancy, and the good time he has had with the fairies, but from any taint of damp, miasmic mysticism he is seraphically free. Indeed, Francis Thompson's remarks about 'the child's faculty of make-believe raised to the Nth power' in his essay on Shelley might be one and all applied to Li Po with appropriateness. His poetry shows no syntactic torture, no tangled symbolism, no hard struggle with words such as characterize all mystic utterances. And his fairies must not be taken as symbols of inner experience; they are so 'human, all too human.' 'You Sien' (Fairyland Visited) has been the favorite theme of Chinese poets. But the fairies in the 'You Sien' poems usually have their prototypes in real human beings. The poet records an actual event either public or personal in terms of fairies. It is mystification not mysticism that the poet aims at. One may note in this connection an amusing mistake in Professor Giles's very readable book on Chinese literature. At the end of Chapter I in Book V of A History of Chinese Literature, Professor Giles gives a complete version of Ssu-K'ung Tu's 'philosophical poem, consisting of twenty-four apparently unconnected stanzas'. This poem, according to Professor Giles, 'is admirably adapted to exhibit the forms under which pure Taoism commends itself to the mind of a cultivated scholar.' This is what Professor Giles thinks Ssu-K'ung Tu to have done, but what Ssu-K'ung Tu really does is to convey in imageries of surpassing beauty the impressions made upon a sensitive mind by twenty-four different kinds of poetry—'pure, ornate, grotesque', etc. The 'twenty-four apparently unconnected stanzas' are grouped under the title 'Shih P'ing' (Characterisations of Poetry). Professor Giles has, at his own peril, ignored the title and then, with an ingenuity quite admirable in itself, translated a piece of impressionistic criticism into mystical poetry par excellence. Traduttori traditori! We have made a rapid review of 'Old' Chinese poetry and noted its defects, or rather deficiencies in love-poetry and philosophical poetry. But 'Old' Chinese poetry has the qualities of its very defects with other redeeming features in the bargain. If not impassioned, it is airy and graceful. If not profound, it is at least free from obscurity or fuliginousness. After all, the most beautiful girl can give only what she has, and it would be sheer willfulness to reprove apple-trees for not producing peaches. Anatole France said: 'Assuredly we love poetry in France, but we love it in our own way; we insist that it should be eloquent and we willingly excuse it from being poetic.' We need but substitute the word 'France' by the word 'China,' and the whole saying would apply pat to 'Old' Chinese poetry. Notes: [1] A great poet omitted in H.A. Giles, A History of Chinese Literature. [2] See W.J.B. Fletcher, More Gems of Chinese Poetry, p.145. [3] See Li Shang-yin's 'Poems Without Subjects', Mr. Fletcher has translated one of them, and that wrongly. [4] Ibid. [5] See Belgion, Our Present Philosophy of Life, pp.30 ff. [6] Cf. Mr. Arthur Waley's interesting essay on 'The Limitations of Chinese Literature' in 170 Chinese Poems, particularly pp.18-19. [7] Concluding lines of 'Home-ward Again', from Giles, A History of Chinese Literature, p.130. Cf. 'Returning to the Fields,' translated by Mr Waley in 170 Chinese Poems, p.113. [8] Concluding lines of the poem on a trip to Sieh Chuan. [9] Concluding lines of 'The River Chu'; from Fletcher, More Gems of Chinese Poetry, pp.72, 74. [10] Cf. Nietzsche's animadversions on German thought in Beyond Good and Evil, § 23. [11] Cf. the Section on 'Temper of East and West' in Watts-Dunton's excellent article on poetry in the Encyclopaedia Brittanica. |