|

|||||||||

|

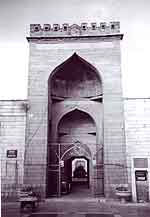

NEW SCHOLARSHIPBOOK REVIEWTHE STONES OF ZAYTON SPEAKWu Wenliang, revised by Wu Youxiong, Quanzhou zongjiao shike (Religious inscriptions of Quanzhou), Beijing: Kexue Chubanshe, 2005, 648pp., +975 black and white illustrationsWu Wenliang, Quanzhou zongjiao shike (Religious inscriptions of Quanzhou), Beijing: Kexue Chubanshe, 1957 (1st ed.), 66pp., +94 pages of black and white platesChen Dasheng, Quanzhou Yisilanjiao shike (Islamic inscriptions of Quanzhou), Yinchuan: Ningxia Renmin Chubanshe, 1984. Fig. 1 Main entrance of the Ashab Mosque, Quanzhou, built in 1310. Religious inscriptions of Quanzhou 2nd ed., plate A13.3. All plate references below are taken from this edition.

Fig. 1 Main entrance of the Ashab Mosque, Quanzhou, built in 1310. Religious inscriptions of Quanzhou 2nd ed., plate A13.3. All plate references below are taken from this edition.

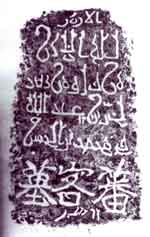

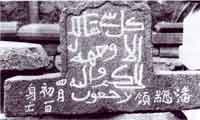

Fig. 2 Three Muslim tombs at Ling Shan, one of the main Muslim burial sites in Quanzhou in the Yuan and Ming dynasties. Plate A34.2  Fig. 3 Tombstones with Arabic and Chinese writing. The Chinese text reads, "Tomb of a foreign trader [fanke]", though this and the Arabic words "tomb area" framing the inscription above and below were probably added at a later date to the main body of the Arabic text. Probably dating from the Southern Song. Plate A76

Fig. 3 Tombstones with Arabic and Chinese writing. The Chinese text reads, "Tomb of a foreign trader [fanke]", though this and the Arabic words "tomb area" framing the inscription above and below were probably added at a later date to the main body of the Arabic text. Probably dating from the Southern Song. Plate A76

Fig. 4 Carved lotus tomb decoration, Yuan dynasty. Plate A131 The port city of Zayton was described by Marco Polo as "one of the two greatest havens in the world" and "the Alexandria of the East". The location of Zayton was the subject of a heated debate amongst 19th-century Orientalists, with arguments raised in support of various cities along in southern China, including Guangzhou, Zhangzhou and Hangzhou.  Fig. 5 Inside of the Ashab Mosque, Tonghuai Gate Avenue, Quanzhou. Photograph taken at the site of the prayer hall, facing west in the direction of prayer. The area outside the Tonghuai Gate was one of the major Muslim districts and home to the Pu clan. Plate A12.1  Fig. 6 A similar picture taken in 1958, showing strewn pieces of the stone pillars of the prayer hall that have since been erected, and a number of tombs relocated to the Quanzhou Maritime History Museum. Plate A180 In 1920, Henri Cordier presented Persian, Chinese and European sources to show that Marco Polo's Zayton was in fact Quanzhou in Fujian province, which had been a major port city since the Tang dynasty.[1] The name Zayton (or Zitun in Arabic, which when written in Arabic script can also be pronounced as "zaytun" meaning olive) derives from the city's popular Chinese name of Citong, after the coral trees (Erythrina variegata) that once lined the streets of the city. However, research on this once-great city was initially hampered by a lack of published material evidence of the cosmopolitan trading community that had flourished there during the Yuan dynasty (1206-1368). The first edition of Religious inscriptions of Quanzhou (referred to below as "the 1st edition") was published in 1957. It was the first major academic publication in which archaeological findings linking the famous medieval port city of Zayton with the site of modern Quanzhou were gathered and discussed. It included illustrations of some two hundred stone items taken from the grave sites and ruined monuments of the religious communities that lived in Quanzhou during the 13th and 14th centuries. These included stone inscriptions in a dozen languages, some of which were translated into Chinese, as well as decorative stone carvings and tomb monuments. The author, Wu Wenliang, who based the text on his own archaeological findings, was a high school teacher and amateur collector in Quanzhou. For two decades he spent his free time combing the surrounding countryside for interesting fragments of carved stone. In 1953, Wu Wenliang donated his private collection to the newly founded Communist state, and later participated in the preparations for the opening of the Quanzhou Maritime History Museum, where his collection is housed. Wu Wenliang kept augmenting this manuscript until his research activities were curtailed by the onset of the Cultural Revolution.  Fig. 7 The Ling Shan site in the 1920s, showing four stone pillars of what was probably a Ming dynasty prayer hall. This was the site of a Muslim cemetery from the Yuan dynasty. Plate A32 The second edition of Religious Inscriptions of Quanzhou, published in May 2005 (referred to as "the 2nd edition"), includes Wu Wenliang's own additions to the 1st edition, as well as further findings and research carried out by his son Wu Youxiong. Complete transcriptions and Chinese translations of all of the Arabic inscriptions are given, as well as Chinese translations of most of the inscriptions in languages other than Arabic. Wu Youxiong completed a draft manuscript for the 2nd edition in the early 1980s, but publication of the book was delayed for two decades, due to problems obtaining funding and publication rights over new photographs of the stone items housed in the Quanzhou Maritime History Museum. This extra time has allowed for new academic findings to be incorporated into the book, especially in relation to Nestorian Christian inscriptions.  Fig. 8 The foyer of the Quanzhou Maritime History Museum. This is the main institution where stones catalogued in Religious Inscriptions of Quanzhou are housed. The 2nd edition is a well-presented catalogue of some 600 stone remains of the religious communities of medieval Quanzhou. The items are arranged by religion into seven sections—Islam, Christianity, Manicheanism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Daoism and Folk Religion—with inscriptions and other carved stone fragments from Islamic monuments constituting over half of the items. What is perhaps the most exciting discovery for readers of the catalogue is the evidence of the rich tradition of decorative carving that flourished in Quanzhou during the Yuan dynasty, which is clearly depicted in the Islamic, Christian, Hindu and Buddhist chapters of the book.

Figs 9 and 10 The earliest (left, 1171CE) and latest (1381) of the dated Arabic tombstones unearthed in Quanzhou. The contrast in style of the two inscriptions indicates the evolution of a sophisticated, Islamic stone-carving industry during this period, especially during the ninety years of Mongol rule (1279-1367). Plates A30 and A55.1 The Islamic section is the most systematically researched. In addition to commentary on the individual stone items, it incorporates essays by Wu Youxiang on the Islamic history of Quanzhou and relevant extracts from old Chinese texts. The transcription and translation of the Arabic inscriptions is diligently performed by Hua Weiqing, who also notes the passages taken from the Quran, but sadly does not make sufficient use of the excellent collaborative work on the same stone inscriptions presented in Chen Dasheng's Islamic Inscriptions of Quanzhou (1984). No English translations are attempted, a task competently accomplished by Chen Dasheng. THE SITESMost of the stone items in this catalogue were found at sites to the east and south of the old city wall of Quanzhou. The Tonghuai Gate area is where the ruins of the Ashab Mosque are located, and includes the grounds of an old Muslim cemetery. This area is of particular historical interest as it was once home to Pu Shougeng's clan, the wealthiest Muslim merchant clan in Quanzhou during the Yuan dynasty and that best documented by historical sources (see the Editorial of this issue). Dozens of tombstones and grave monuments were unearthed during local construction projects in the 1950s, and initially stored at the Ashab Mosque before being relocated to the Quanzhou Maritime History Museum. (Figs 5 & 6) Another significant source of artefacts was the Islamic cemetery at Ling Shan, which is also the site of tombs dedicated to two of the Companions of the Prophet. (Fig. 7, for legendary stories about the China-bound Companions, click here.)  Fig. 11 Example of one of the complete tombstones. The text shown here reads, "Here lies the martyr, Amir Sayyid Ajall Toghan Shah bin Sayyid Ajall Umar bin Sayyid Ajall Amiran bin Amir Isfahasalar(?) of the Bakr family of Bukhara. May God bless their graves and make Paradise their permanent abodes. Died on 9 Safar 702 (1302)." Plate 44.1, translation adapted from Islamic inscriptions of Quanzhou

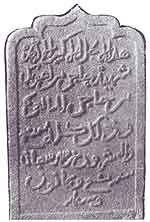

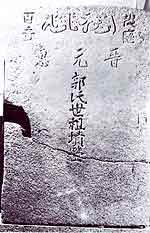

Fig. 11 Example of one of the complete tombstones. The text shown here reads, "Here lies the martyr, Amir Sayyid Ajall Toghan Shah bin Sayyid Ajall Umar bin Sayyid Ajall Amiran bin Amir Isfahasalar(?) of the Bakr family of Bukhara. May God bless their graves and make Paradise their permanent abodes. Died on 9 Safar 702 (1302)." Plate 44.1, translation adapted from Islamic inscriptions of Quanzhou  Fig. 12 Tombstone with Chinese words inscribed in both characters and Arabic script (xiaojing). The Chinese characters on the sides read, "Established residence in Huijin, Baiqi [district]." The line of Chinese down the centre reads, "The grave of Shide of the Guo family of the Yuan dynasty (Yuan Guo-shi Shizu-gong fenmu). This Chinese sentence is repeated in Arabic script at the top of the tombstone (Ayn Gwor Dagan Gun da mu ("Dagan" or Deguang is the name of the Shizu ancestor, according to lineage documents of the Guo clan). Plate A78

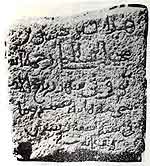

Fig. 12 Tombstone with Chinese words inscribed in both characters and Arabic script (xiaojing). The Chinese characters on the sides read, "Established residence in Huijin, Baiqi [district]." The line of Chinese down the centre reads, "The grave of Shide of the Guo family of the Yuan dynasty (Yuan Guo-shi Shizu-gong fenmu). This Chinese sentence is repeated in Arabic script at the top of the tombstone (Ayn Gwor Dagan Gun da mu ("Dagan" or Deguang is the name of the Shizu ancestor, according to lineage documents of the Guo clan). Plate A78The site where each of the stone items was found is recorded in the 2nd edition, which makes possible the composition of a detailed map of the sacred sites of the Muslim, Christian, Hindu and other religious communities that lived in Quanzhou during the Yuan dynasty. The current location of most of the items is also given, though this is not possible for many of the large grave monuments and structures photographed in the 1930s and 1950s that have since been destroyed, such as the corridors of stone archways (paifang) that stood outside the East Gate. The main institutional home for the items included in the 2nd edition is the Quanzhou Maritime History Museum. (Fig. 8) Other museums that hold major collections of stone items are the Museum of History and Anthropology at Xiamen University, and the Quanzhou Studies Centre of the Quanzhou Teachers" College where Wu Youxiong is now based. Further collections are housed in local museums near to archaeological sites in the greater Quanzhou district. THE STONE INSCRIPTIONSThe majority of the Islamic inscriptions on the stone artefacts are passages from the Quran, originally used to ornament mosques, grave monuments and tombstones in Quanzhou. Around seventy complete or partial tombstone inscriptions are presented in the 2nd edition, thirty of which have legible dates of death. These dates range from the mid-12th to the late-14th centuries, and are concentrated in the middle period of the Yuan dynasty (early-13th century). The inscriptions are recorded in a range of Arabic scripts and are carved with varying degrees of craftsmanship. (Figs 9,10 & 11)  Fig. 13 Another bilingual tombstone, with Arabic on the obverse and Chinese on the reverse. The Arabic reads, "Everything will perish except His own face (Quran 28:88). Plate A92.1

Fig. 13 Another bilingual tombstone, with Arabic on the obverse and Chinese on the reverse. The Arabic reads, "Everything will perish except His own face (Quran 28:88). Plate A92.1 Fig. 14 Reverse of Fig. 13. The Chinese text reads, "The official of Yongchun county, the Dalu(huachi)... ." The post of daruhachi (a Mongolian title usually translated into Chinese as zhangyinguan, meaning seal holding officer or overseer) was one of the senior posts in the Mongol bureaucracy. Plate A92.2

Fig. 14 Reverse of Fig. 13. The Chinese text reads, "The official of Yongchun county, the Dalu(huachi)... ." The post of daruhachi (a Mongolian title usually translated into Chinese as zhangyinguan, meaning seal holding officer or overseer) was one of the senior posts in the Mongol bureaucracy. Plate A92.2A small number of the Islamic tombstones are inscribed with Chinese characters either on the reverse side, or arranged around an Arabic inscription on the obverse side. Where the Chinese appears on the obverse, it appears that the tombstones were either erected in the Ming dynasty, when Chinese writing had a more prominent role in the local Muslim community, or the Chinese inscription was added after the tombstone was first erected. (Figs. 12,13,14 & 15)  Fig. 15 Another bilingual tombstone inscription. The main text is in Arabic, which reads: "Everything will perish except His own face. To Him belongs the Command, and to Him will ye be brought back." (Quran 28:88) The Chinese text reads, "The Commander of the Foreigners [fan]. Died on the 1st of the Fourth month." Plate A93

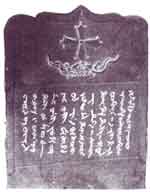

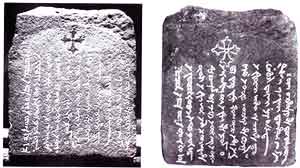

Fig. 15 Another bilingual tombstone inscription. The main text is in Arabic, which reads: "Everything will perish except His own face. To Him belongs the Command, and to Him will ye be brought back." (Quran 28:88) The Chinese text reads, "The Commander of the Foreigners [fan]. Died on the 1st of the Fourth month." Plate A93The Arabic text of the inscriptions—and Arabic is the dominant language used both then and now for such inscriptions—is sometimes supplemented by Persian, Chinese or xiaojing (Chinese written in Arabic script). The written languages used on Christian inscriptions, of which nineteen examples are presented in the catalogue, are more diverse. The dominant language appears to have been Weiwu'er (Gaochang Uyghur) written in the Syriac script (Fig. 16), though some of the inscriptions in Syriac script are not fully described in the catalogue. (Figs 17 & 18) The catalogue presents several bilingual tombstone inscriptions in Weiwu'er and Chinese, as well as bilingual texts in a Turkic language, using Phagspa script, and Chinese. (Fig. 19) There are two Latin-inscribed fragments, originating from the small Franciscan community that lived in Quanzhou in the 13th century. These Christian inscriptions have been the subject of much academic research, and some of this research is reviewed by Wu Youxiong.[2] The widespread use of Gaochang Uyghur on the Nestorian monuments, in combination with the dominance of central Asian artistic styles and motifs on the Christian, Islamic and Buddhist monuments, highlights the central role played by Mongol and Semu (central and western Asian subjects of the Yuan empire) migrants in the religious institutions of Quanzhou during the Yuan.  Fig. 16 Nestorian tombstone. Syriac text below a motif of the Nestorian cross on swirling clouds. The text begins, "In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit..." Syriac is the most common of several scripts found on Nestorian tombs in Quanzhou. Plate B21.2

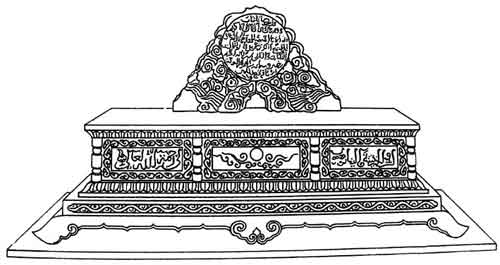

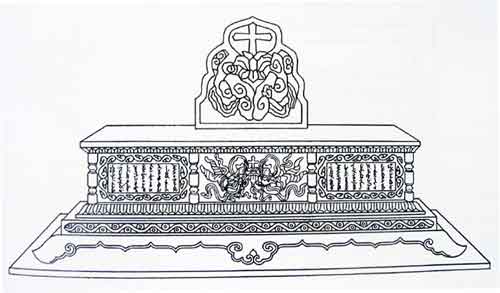

Fig. 16 Nestorian tombstone. Syriac text below a motif of the Nestorian cross on swirling clouds. The text begins, "In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit..." Syriac is the most common of several scripts found on Nestorian tombs in Quanzhou. Plate B21.2 Fig. 17 Reverse of Fig. 16. The Chinese text gives the name, title, address and death date of the deceased. MUSLIM AND NESTORIAN GRAVE MONUMENTS Fig. 18 Nestorian tombstone in Syriac script. The text is identified by Niu Ruji as Weiwu'er (Gaochang Uyghur) with extensive borrowings from Syriac. The text reads, "In the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. In the year 1613 [1301] by the calendar of Alexander the Great, or on the 26th of the tenth month of the year of the ox by the Chinese [Taohuashi, i.e. Taugas, the Byzantine and Islamic name for China] calendar. The son of Takmis Ad Ayr of Gaochang, Ostak Taskhan, came to Zaytun City in his 67th year and completed his God-sent mission. May his soul rest peacefully in heaven. Amen." Plate B17.2 The Muslim and Nestorian grave monuments found in Quanzhou are of two styles. The most common is the ridged grave monument. Several dozen examples of these are included in the 2nd edition, a sample of possibly many thousands that remain obscured or buried in the Quanzhou district. In many cases they can be distinguished as being either Muslim or Nestorian by their decorative motifs. (Figs 21 & 22) The second style is the altar-type grave monument, which has a flat top on which a small stone grave marker would once have been placed. (Figs 23 & 24) Diagrams by Wu Wenliang of Muslim and Nestorian altar-type grave monuments are shown below. (Figs 25 & 26) Relief carvings of plants have been found on both Muslim and Nestorian monuments. On the Nestorian carvings the plant is centred within the frame of the relief carving. Similar carvings on Islamic grave monuments show the end of a blooming branch or a bunch of cut flowers leaning towards the left of the frame, respecting the general aversion in Islamic art to complete representations of God's creations. (Figs 27 & 28)  Fig. 19 Nestorian tombstone with bilingual inscriptions, below motif of a Nestorian cross, supported by a lotus flower and two angels. Plate B21.2

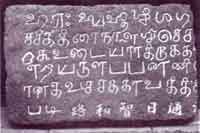

Fig. 19 Nestorian tombstone with bilingual inscriptions, below motif of a Nestorian cross, supported by a lotus flower and two angels. Plate B21.2The most common motif found on Nestorian monuments is the Nestorian cross resting on top of a lotus flower, which in turn is supported by swirling clouds. (Figs 29 and 30) In a number of instances, an ornamental cover (huagai), or parasol, is shown over the cross. The tri-partite motif made up of the lotus, the cross and cover resonate with the carvings on Buddhist stone art from Quanzhou.(Figs 31 and 32) Finally, there are a number of stone statues and figures carved in relief included in the 2nd edition, although little attempt is made by the authors to give a systematic presentation of their origins and archaeological significance. A number of illustrations are given below as an example of the figurative carving practices that developed in Quanzhou during the Yuan dynasty. These include Nestorian angels portrayed in a style similar to figurative paintings of apsaras (feitian) from the Dunhuang grottoes, and a striking series of Hindu carvings in bas relief from a pillar of a Hindu temple that was later incorporated in the Kaiyuan Buddhist monastery. (Fig. 33)  Fig. 20 Section of stone inscribed in Tamil and Chinese. Plate D10.1  Fig. 21 An Islamic ridged grave monument, found and now housed at the Ling Shan site. Plate A206.1  Fig. 22 Nestorian Christian ridged grave monuments. Plate B69  Fig. 23 Diagram of an Islamic altar-type grave monument, such as found at many sites in the Quanzhou district. Plate A338  Fig. 24 Diagram of a Nestorian altar-type grave monument. Plate A339 DYNASTIC CHANGE AND SECTARIAN VIOLENCEWith the exception of a small number of tombstones and steles from the late Song and Ming periods, the carved stones of Quanzhou were produced during the ninety-year period of Mongol rule. The stones are testimony to the flourishing of religious institutions of many denominations that occurred in Quanzhou at the time, a situation described by foreign visitors to the port city and by resident European priests. Mongol rule did not, however, bring prosperity to all people in equal measure: non-Chinese people in the city were granted an exalted status which did not, however, extend to former subjects of the Southern Song who also lived in the area.  Fig 25. Carved stone marker from the top of an altar-type grave monument, depicting the Nestorian cross above a lotus and swirling clouds. Plate B3  Fig. 26 Print of a stone marker similar to Fig. 25, taken from a late-Ming dynasty book by the Jesuit Emmanuel Dior on supposed Tang dynasty Nestorian monuments in China. Plate B11 The Yuan dynasty came to an end in Quanzhou with ten years of violent conflict between rival factions of the Mongol military that partially reflected sectarian and religious divisions. The founding emperor of the Ming emerged out of one of these factions, and was also a member of the Mingjiao sect that is understood by historians to have been organised around Maitreyan Buddhist, White Lotus or Manichean beliefs. The establishment of the Ming dynasty was accompanied by a political movement to remove obvious reminders of Mongol rule, including the religious institutions patronised by Mongol and Semu peoples. Most of the temples and mosques in Quanzhou were destroyed or partially destroyed during this period and some, such as the Tamil temple that once stood outside the Tonghuai Gate, survived only as fragments incorporated into new temples built in the early Ming.  Fig. 27 Carved bunch of lotus flowers from an Islamic tomb monument. Plate A131  Fig. 28 Carved branch of a blossoming tea tree from a Nestorian tomb monument. An excellent essay by Wu Youxiong on the sectarian violence in Quanzhou that accompanied the transition from Yuan to Ming rule is included in the 2nd edition. He concludes his essay by characterising the anti-foreign movement of the early Ming within a Marxist-Maoist theoretical framework. He writes:

Fig. 29 Stone marker from a Nestorian grave monument.  Fig. 30 Rubbing of Fig. 29, showing a tri-partite motif, common to many Nestorian stone monuments, made up of a lotus flower, the Nestorian cross and an ornamental parasol (huagai). This may have been understood as a symbol of the Holy Trinity.

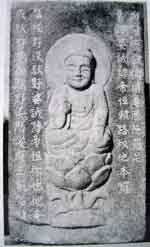

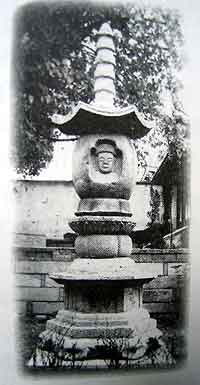

Fig. 30 Rubbing of Fig. 29, showing a tri-partite motif, common to many Nestorian stone monuments, made up of a lotus flower, the Nestorian cross and an ornamental parasol (huagai). This may have been understood as a symbol of the Holy Trinity.While this may not seem particular diplomatic, coming as it does from an academic engaged in research on cultural interaction between Chinese and foreign civilisations, it is perhaps an expression of resignation to a certain form of party-ordained historiography by an author whose private and working life had been shaped by the politics of the Communist period. The 1st edition went to press when the author of the original preface, the eminent scholar Chen Mengjia, had been labelled a "rightist". This delayed publication until Wu Youxiong's father, Wu Wenliang, wrote a new preface. The book came out in 1957, a year before the "campaign against religious privilege campaign" (fan zongjiao tequan yundong) that signalled the end of the publication of academic work relating to religion until after the Cultural Revolution. Wu Wenliang kept up a correspondence with foreign scholars relating to the foreign-language inscriptions on the Quanzhou stones. Some of this correspondence was produced in the early years of the Cultural Revolution as evidence that Wu Wenliang was "colluding with foreign counter-revolutionary factions", for which he lost his life.  Fig. 31 Front of a four-sided pillar inscribed with Chinese Buddhist scriptures, with a seated Buddha figure carved in relief. The lotus, body and crown are similar to the Nestorian stone marker of Fig. 29, hinting at common central Asian origins for many of the Buddhist and Nestorian motives found in Quanzhou.  Fig. 32 Buddhist stupa from Kaiyuan Temple, adjacent to the site of the Quanzhou Maritime History Museum. This stupa has a pagoda spire and a lotus base. Plate E16 Wu Youxiong began to arrange his father's papers in the latter years of the Cultural Revolution, but having them republished was not a simple matter. The Quanzhou Maritime History Museum had custody of his father's former collection. They had added many new items, and spent large sums of money to catalogue, display and conduct research on the enlarged collection. The Museum was unwilling to allow either full access to the collection, or publication rights to photographs, for free. Wu Youxiong did not have an academic post, making it difficult for him to obtain funding for his research. According to the main preface of the 2nd edition, the breakthrough came in the early 1990s, when UNESCO provided a publication grant. The stones of Quanzhou, survivors of the sectarian violence of the early Ming and the Maoist periods, can now be examined by scholars world-wide, thanks to this recent publication, which documents a unique period of Chinese religious and cultural history. [AHG]  Fig. 33 Angels supporting the Nestorian cross above a base of a lotus flower and swirling clouds. These angels show a likeness to apsara seen in Dunhuang murals, providing another link between the Quanzhou stonework and central Asian art from the pre-Mongol period. Plate B31 Notes:[1] Marco Polo and Rustichello of Pisa et al, The Travels of Marco Polo, 2 vols, ed. Henry Yule and Henri Cordier, New York: Dover, 1993; e-text available online via The Project Gutenberg: http://manybooks.net/titles/polom12411241012410-8.html, vol. 2, pp.285-299. [2] For example, Wu Youxiong draws on a recent essay by Niu Ruji when describing the Phagspa inscriptions: Niu Ruji, "Cong chutu beiming kan Quanzhou he Yangzhou de Jingjiao laiyuan" (A look at the route of transmission of Nestorianism based on inscriptions unearthed in Quanzhou and Yangzhou), Shijie zongjiao yanjiu (Research on world religions), 2003:2, pp.75-79. [3] Wu Wenliang, revised by Wu Youxiong, Quanzhou Zongjiao Shike (Religious inscriptions of Quanzhou), Beijing: Kexue Chubanshe, 2005, pp.310-11. References:Pearson, Richard, Li Min and Li Guo, "Quanzhou Archaeology: A Brief Review", International Journal of Historical Archaeology 6:1 (2002), pp. 23-59. Schottenhammer, A., ed., The Emporium of the World: Maritime Quanzhou, 1000–1400, Leiden: Brill, 2001. |