|

|||||||||

|

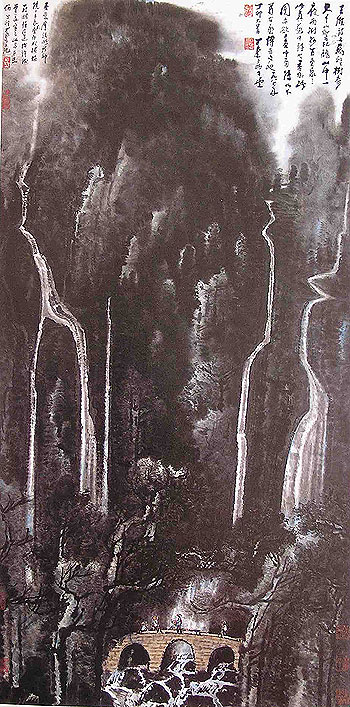

NEW SCHOLARSHIPA Century of Li Keran: Commemorating the Centenary of a guohua ArtistClaire RobertsLi Keran (1907-89), one of the most important official Chinese artists of the second half of the twentieth century, was commemorated in Beijing on the occasion of the centenary of his birth with a major exhibition and international seminar at the National Art Museum of China on 5-6 November 2007, and a series of publications. The commemoration, initiated by the Li Keran Art Foundation, was organised by the Ministry of Culture and the China Federation of Literary and Art Circles with the Central Academy of Fine Arts where Li was a professor for many years, the National Art Museum of China and the Chinese Artist's Association. The gathering also boasted a long list of supporters and sponsors including local auction houses, cultural promotion companies and a Taiwan publisher. The celebrations culminated in a lavish dinner at the Diaoyu Tai State Guesthouse with entertainment compèred by Ni Ping, one of China's best-known television personalities. These activities reflect the mix of art, politics, business and the media that surrounds the arts in China today.  Promotional advertising for the Li Keran exhibition with the Beijing Hotel in the background. November 2007. Photograph by Claire Roberts. Li Keran, who was forty-two at the time of the founding of the People's Republic of China, embraced the challenges and opportunities with which he was confronted. Born in Xuzhou, Jiangsu, to illiterate parents, he excelled at art from an early age. In 1925, he graduated from the Shanghai Art College and went on to post-graduate study in Western art at the National Art Academy in Hangzhou. His teachers included the French modernist Andrè Claudot (1892-1982) with whom he studied drawing and oil painting. Li painted propaganda art during the Sino-Japanese War and in 1946 he was invited by Xu Beihong (1895-1953) to teach brush and ink painting at the Beiping National Art College (Beiping guoli yizhuan). There he came into contact with Qi Baishi (1864-1957) and Huang Binhong (1865-1955), two of China's most influential twentieth-century brush and ink painters. Despite his training in oil painting, in the 1940s Li Keran turned to the more patriotic and less expensive medium of brush and ink and excelled in figure painting, in the literati style. In 1950, Li was appointed Associate Professor in the Department of Chinese Painting at the newly established Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing and he published an influential essay titled 'On the Reform of Chinese Painting' in the inaugural issue of Art (Meishu), the magazine of the Chinese Artists' Association. Reflecting the revolutionary spirit of the times Li Keran invoked the words of the leader of the Communist Party Mao Zedong and called on artists to immerse themselves in the lives of ordinary people (shenru shenghuo). He also argued for the retention of useful elements of China's rich cultural and artistic heritage as well as the need to draw from external sources, notably scientific principles embodied in Western art. In 1954, Li Keran put his own theory into practice and travelled south of the Yangtze on a painting trip with fellow artists Zhang Ding (b.1917) and Luo Ming (b.1912). During that trip Li spent time in Hangzhou with Huang Binhong, who was then China's most senior landscape painter. The three-month journey marks a major turning point in Li Keran's art. Thereafter, he concentrated on landscape painting that was closely observed, drawing on his experience of Western realist art and Chinese brush and ink painting. Beginning in 1954, he also began to experiment with the layered ink technique (jimo fa) that became a hallmark of his mature style. In the 1970s, Li Keran was encouraged to return from his disgrace during the Cultural Revolution as a 'black artist' to make public art. Among the tasks assigned to him were the creation of monumental landscape paintings for the Nationalities Hotel (Minzu fandian) in Beijing and the Department of Foreign Affairs, paintings for presentation as official gifts to visiting heads of state and a massive work representing the revolutionary site of Jingang Mountain in Jiangxi province for the Chairman Mao Mausoleum in Tiananmen Square. Li was an influential educator who taught at the Central Academy of Fine Arts since 1946. In 1979, he lead a post-graduate class in landscape painting at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, the first such course in China, and in 1981 was appointed inaugural Director of the Chinese Painting Research Academy (Zhongguo hua yanjiu yuan), instilling in a generation of practitioners his new landscape painting method of using brush and ink to record the actual landscape. Today, Li Keran is renowned for his black landscape paintings, for which he was severely criticised during the Cultural Revolution, but which he continued to paint in the years until his death in 1989. The November 2007 Li Keran seminar brought together arts officials, art historians, scholars and artists from China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea and Australia. Papers explored the position of Li Keran and his contribution to twentieth-century Chinese art. The noted art historian Lang Shaojun (Chinese Art Research Institute, Zhongguo yishu yanjiu yuan) described Li Keran's art as 'a milestone in new landscape painting', referring to his union of realist art and Chinese brush and ink technique. It was impossible, Lang said, for Li Keran to have escaped the conjunction of art and politics at that time, going on to observe that while he painted 'red landscapes' in the early 1960s, he never forgot the fact that he was an artist. Shui Tianzhong (also of the Chinese Art Research Institute) called Li Keran an innovator and a brave artist, for whom black was never black enough. And Wang Luxiang (Li Keran Foundation) reminded the audience just how difficult it was to be an artist in the 1950s. He went on to say that it was fortunate Li Keran lived at that time because he rose to the challenge and developed a new artistic language that successfully responded to the changed political and artistic climate. Chen Ruilin (Art Academy, Qinghua University) described Li Keran as a tragic talent-in the sense that he lived during a difficult period and suffered ill health during the latter part of his life which prevented him from attaining the ultimate goal of moving away from the depiction of things and achieving expression of the self.  Li Keran, 'Inspired by Wang Wei's poetry', ink and colour on paper, 1987. Reproduced in Shiji Keran: jinian Li Keran danchen yibai zhou nian, zuopin ji (A century of Keran: Commemorating the 100th anniversary of Li Keran's birth), Changchun: Jilin meishu chubanshe, 2007, p.245.

Li Keran, 'Inspired by Wang Wei's poetry', ink and colour on paper, 1987. Reproduced in Shiji Keran: jinian Li Keran danchen yibai zhou nian, zuopin ji (A century of Keran: Commemorating the 100th anniversary of Li Keran's birth), Changchun: Jilin meishu chubanshe, 2007, p.245.

Former students spoke of Li Keran's good character. Wang Qingli, who was confined together with him in an 'ox-pen' (niupeng) during the Cultural Revolution, commented on Li's lack of interest and participation in factional struggles. Mei Mo noted Li's fear of high officials and their demands. And of his painting practice Li Song observed that Li Keran painted quickly during the 1940s (in the manner of a literati artist) but that in the 1950s, when his style of painting and subject matter changed dramatically, he began to paint very slowly. And Zhang Ping recalled Li Keran's advice to students that they should paint a subject as if they had just been dropped to earth from the moon. In question time there was vigorous discussion about whether Li Keran's best work was created in the 1950s and 1960s or at the very end of his life in the 1970s and 1980s. He Huaishuo, a Taiwanese artist and art writer, argued that the earlier period saw Li's greatest creativity and innovation, but the great majority of mainland critics and artists insisted that it was the late period owing to the accumulation of knowledge and experience necessary for Chinese painting, with Li Keran no exception to this rule. He Huaishuo asked what kind of emotions Li Keran expressed in his dark, full and rather heavy landscape paintings, seeing in them a latent critique of the times. He urged mainland art historians to go beyond the analysis of brush and ink technique and examine the ideas and sentiments that lie behind the paintings. This question and comment provoked heated discussion between He Huaishuo and mainland art historians, artists, and keepers of the Li Keran flame. Li Keran is a significant twentieth-century Chinese painter. As an artist and an art educator he worked to make sense of his own life during a period of Chinese history that was marked by fundamental social change. His legacy is a relatively small number of carefully considered works, including oil paintings, pencil sketches, pencil drawings, brush and ink paintings (landscapes and figures) and calligraphy, a volume of writings on art and a large number of students and followers who perpetuate his once new style. The conference, publications and associated events highlighted the official reverence and respect with which Li Keran is regarded as an artist and art educator, particularly in Beijing and northern China, though he was himself was from the south. It is interesting to note, however, that the great majority of Li's oeuvre remains in the care and custody of the family and the Li Keran Art Foundation. The collection of the National Art Museum of China currently contains few works by Li Keran. On the centenary of Li Keran's birth, the artist's family and the Li Keran Foundation worked together with official arts organisations to pay tribute to Li Keran as father, teacher, mentor and innovator who worked diligently and creatively within the constraints of his time. The conference showed that it can be difficult to examine the art of the second half of the twentieth century in a dispassionate and objective manner. Perhaps the recent past of Chinese art is too close, too contested and too painful. While in their spoken remarks a number of speakers hinted at a growing interest in moving beyond hagiography to more nuanced interpretations of twentieth century art history, a truly independent approach to art historical research is still some way off. The celebrations confirmed the complexity of the Chinese art world where an individual's artistic legacy is inextricably implicated in narratives that are socio-political as well. Claire Roberts is a graduate of the brush and ink painting department, Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing (1981). She was an invited speaker at the conference at which she presented a paper titled 'Accumulated ink: the landscape paintings of Huang Binhong and Li Keran'. |