|

||||||||

|

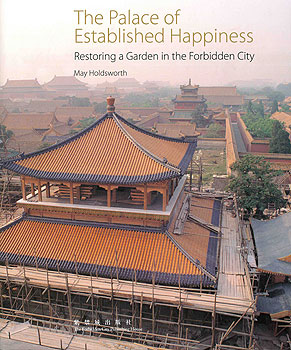

NEW SCHOLARSHIPBook ReviewMay Holdsworth, The Palace of Established Happiness: Restoring a Garden in the Forbidden City, Beijing: Forbidden City Publishing House, 2008, 220pp with illustrations.Geremie R. Barmé  The conflagration that consumed the Qianlong-era Palace of Established Happiness (Jianfu Gong) in the Forbidden City on 26 June 1923 was the penultimate dramatic episode in the living history of China's imperial palace. Untold antiquities were said to have been lost as a result of the connivance of duplicitous eunuchs and the corrupt dealings of the Imperial Household Department (Neiwu Fu). In the aftermath, a feckless dethroned emperor, Puyi, ordered the expulsion of most of the palace servants before both he and the rump of the Qing court were themselves sent packing the following year. In this lavish and highly readable account, May Holdsworth recounts the story (and conflicting truths) of the destruction of the Palace of Established Happiness, as well as the drawn-out process involved in its recent rebuilding. Just as the fire of 1923 was regarded as a symbolic moment in the Republican-era history of the Forbidden City, so the reconstruction of the Palace of Established Happiness has been taken by some, not least of all Ronnie Chan, the Hong Kong businessman and supporter of the China Heritage Fund that financed an ambitious project of reconstruction, to be a mark of the re-emergence of the grandeur of China itself. The Palace of Established Happiness is located in the northwest precinct of the Forbidden City, or more precisely at the northern end of the outer western corridor (Wai Xi Lu) of the city. It was built by order of the Qianlong Emperor (r.1736-95) in 1742, during the early flourishing of his rule. It was only one of a number of garden retreats that he would have constructed, both in the formal centre of Qing power, the Forbidden City, and in the garden palaces outside the city. That emperor (and indeed his predecessors as well as his successors) believed that an attention to gardens, and the lavishing of imperial largesse on them, were integral to the art of rulership. As Qianlong observed:

Shanghai-born May Holdsworth has written a number of works on the Forbidden City. The present book is a study of the Palace of Established Happiness and a chronicle of its rebuilding from the late 1990s. Richly illustrated and elegantly written, Holdsworth's account also offers an often chatty diary of the trials and tribulations of the reconstruction team, in particular of its tenacious and devoted onsite manager, Happy Harun (she is the daughter of a Shanghainese mother and a Jakarta-born Hakka father who changed the family name from Qiu to Harun during the Sukarno era). A geologist by training, Happy was a personal assistant to Ronnie Chan before finding herself involved in, and them obsessed with, this fascinating rebuilding project. Restoring a Garden in the Forbidden City follows the history of this extraordinary venture. Offering some detail of the various bureaucratic claims on the site, and allowing the reader some rare insights into the workings of China's leading museum, the book also offers crucial details of the actual rebuilding: the sourcing and manufacture of the thousands of liuli glaze tiles for the roofs of the buildings, the making of the 'gold bricks' (jinzhuan) used for flooring, the ornate painting of eves, the elaborate process involved in creating the 'painted ground' (dizhang) of columns, the reconstruction of the mosaic-like 'tiger-skin walls' (hupi qiang), and so on. It also introduces us to the delicate skein of relationships that brings traditionally trained craftsmen into a major project that itself showcases the fragile heritage of Chinese material culture, and its tenuous maintenance. For, in the process of rebuilding the Garden of Established Happiness, those who initiated and have overseen the project also discovered the need to preserve techniques that themselves are as endangered as many of the old structures in the Forbidden City itself. The author gives us insights into how the team working on the reconstruction went about determining the style, extent, use and decoration of the structures in the compound of the Palace of Established Happiness. It is an account that tells us much about other aspects of the Forbidden City. For all of the archival riches related to imperial rule during the Qing era, actual details of palace buildings, their evolution and information on the lives lived therein are quite elusive. Often it is only through poems from the imperial hand, or a careful reading of the Imperial Ledgers—the accounts of the imperial day—that some sense of how buildings were used, and how they changed in function, can be appreciated.  The Pavilion of Prolonged Spring (left) and the Pavilion of Tranquil Ease (right), with Prospect Hill visible in the distance. Photo: GRB. Published with the permission of the China Heritage Fund. As is the case with other projects of tangible heritage recuperation, those involved in the rebuilding of the palace and its attendant gardens were inevitably faced with deciding on the optimal moment to which the restoration would aspire. With the Palace of Established Happiness there were various choices: should it be rebuilt so that it reflected the presumed condition that it had attained (or had been reduced to) on the eve of its destruction on the summer night in 1923? Or would a moment in the nineteenth century, when it was still a part of a thriving palace, be more appropriate? In the event, it was decided that the buildings and gardens should recover the idealized state of the High-Qing era, some point at the zenith of the Qianlong reign in the mid-eighteenth century. It is an imaginative moment that bespeaks China's last blossoming as a strong, prosperous and unified empire. It is a time that appeals now to ambitious bureaucrats, Qing specialists and patriotic compatriots alike. While this choice might have been the right one for a range of reasons—it certainly resulted in a sumptuous recreation—it is also one that aligns seamlessly with the general 'Qing revivalist style' evident throughout Beijing today. After nearly a century of excoriation, since the late 1990s the Qing era has enjoyed a posthumous renaissance, and it is celebrated in the most lavish and kitsch cultural extrusions. Now it is fashionable to vaunt the age of the Three Emperors (Kangxi, Yongzheng and Qianlong), the acceptable mien of Manchu-Qing China. In terms of the tangible heritage of the former imperial capital, however, the cumulative effect is that a certain dull conformity has descended on the city's complex and layered past. Today, the authorities, the media, specialists in numerous fields and business people tirelessly celebrate the 'gold and jade resplendence' (jinbi huihuang) of the Qing. Not surprisingly, this chimes all too harmoniously with the nouveau-riche temper of the recent reform era. The 'pall of splendour' that Qing-period buildings now cast over Beijing, especially those that enjoyed the munificence of Olympic-era refurbishment, means that quirky historical moments are thoughtlessly (or pointedly) obliterated in favour of an imagined era of glory. The tennis court that Puyi had built in the destroyed garden, or other renovations of the area during the post-Qinglong century and a half of the Mid and Late Qing were excluded from the discussion about the restoration of the Palace of Established Happiness and its garden. The tasteless acts of the legitimate occupants of the palace were nugatory in comparison to the need to let the past serve the present. Anyway, as Holdsworth notes, 'There was no debate about leaving the Garden a picturesque ruin—that wasn't an option.' There was money from the China Heritage Fund to rebuild, and that meant that the devastated remains of the fire, a key site reflecting the Forbidden City's sorry fate in the first half of the twentieth century, would itself be destroyed in favour of restoration. While heritage specialists and historians might like to debate the point, for the patriotic revivalist, however, there are other contemporary dimensions to the recuperation of the past. As Ronnie Chan of the China Heritage Fund and a man of ebullience put it, 'Culture flourishes in times of prosperity and withers in times of turmoil or war. Isn't it appropriate that as China finally re-enters the family of great nations, and as China rises economically and politically on the world scene, that somebody should come along and restore the Garden?'

|