NEW SCHOLARSHIP

The Great Yu | China Heritage Quarterly

The Great Yu Da Yu 大禹

A Temple 禹庙 and a Tomb 禹陵

Sang Ye and Geremie R. Barmé

Fig. 1 The Yu Tomb in the hand of Jiang Zemin 江泽民, former General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party.

As we noted in the March 2007 issue of China Heritage Quarterly, the State Administration of Cultural Heritage listed the ritual ceremonies (jidian 祭典) associated with the Great Yu (Da Yu 大禹) outside in Shaoxing, Zhejiang province as a national cultural intangible heritage property in 2006 (see Bruce Doar, 'Chinese Myths of the Deluge'). On 2 March 2007, the Ministry of Culture further approved the Zhejiang provincial government's proposal of 12 February 2007 that the ritual ceremony for the Great Yu be elevated to national status. It is now classified as one of eight ‘national ceremonies’ (guoji 国祭).[Fig. 1]

As is so often the case with cultural sites in China, the organizational history of Yu Tomb reflects the changing political and economic priorities of the party-state.

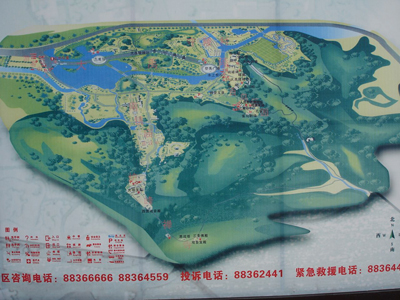

Fig. 2 Overview of the Yu Tomb Scenic Area. Photo: GRB.

In 1950, shortly after the establishment of the People's Republic of China, the Yu Tomb was converted into a primary school under the management of the local government Yu Tomb Township. From 1954, the buildings and cultural artefacts at Yu Tomb were officially overseen by the Shaoxing Cultural Management Committee, although the school remained on the site until 1966. From 1966 to 1976 the area was severely damaged due to political movements and, as part of the purge of the shade of the Great Yu, a pesticide factory located there. Repairs began in 1976 and in 1979 the area was opened to tourism, the management of which was undertaken by the Yu Tomb People's Commune at the behest of the local Shaoxing 绍兴 government.

From 1981 to 1999, control of the area reverted to the Shaoxing cultural bureaucrats who established the Yu Tomb Cultural Protection Office. In 1999, the Yu Tomb Scenic Area Management Office was established and tourism to the site was henceforth managed by the Shaoxing Municipal Tourism Investment Development Company.[Fig. 2]

The Cultural Revolution

According to Chen Weiyu 陈惟于, a man put in charge of restoring the cultural properties at Yu Tomb from 1976 to 1979, the scene that greeted him at the Yu Tomb following the Cultural Revolution was one of devastation. (Chen is now an adviser to the Shaoxing local government on matters related to social development):

During this era the Great Yu was decried as the preeminent one of all emperors, kings, generals and ministers. His statue was destroyed and the head and neck were placed on an open trolley and paraded through the streets of Shaoxing. The buildings of the Yu Temple were turned into a pesticide factory—that's because according to legend the Great Yu was a worm, so it was reasoned that pesticides could kill him once and for all.

Fig. 3 Inscription at the entrance to the ceremonial area at the Yu Tomb. Photo: GRB.

After the Cultural Revolution, when I assigned here the main hall of the Great Yu Temple had a leaky roof and the back wall of the enclosure had collapsed. The floor of the temple itself was covered in moss. The pesticide factory might have been relocated, but they had stripped the place, including the main door, before they left. Many of the paving stones used for the floor had also disappeared and they are no longer produced. I was able to buy a load of them from the local peasants who had taken them from ancient graves.

At the entrance where they now have Jiang Zemin's calligraphic inscription used to be a field of big containers used for compost. We employed local farmers to remove the cesspots, one yuan per pot. Overall, they were very help full. 'Great Yu was a good man,' they said. 'We'll move the shit so you can repair Yu Tomb, though we wouldn't help out if it were anything else.'

It was relatively easy to rebuild the temple, what couldn't be replaced were all the ancient trees that had been cut down. I found two large pagoda trees in town and the owner didn't even charge me. He donated them for free. They are now celebrated as the 'Great Pines of Yu Temple' (Yu miao cansong 禹庙苍松), even though they're not. The man who donated them is Zhu Zhonghua 朱仲华, he should be remembered.[Fig. 3]

Fig. 4 The new altar at the ceremonial ground looking towards the Kuaiji Shan on which a statue of Great Yu can just be made out. Photo: GRB.

The National Ceremony 国祭

From 1949 to 1994 there were no public commemorative ceremonies held at the Yu Tomb. In 1995, limited celebration of the legendary figure of the Great Yu was once more allowed, and even supported by the local authorities and the Shaoxing community as a whole. As mentioned earlier, in 2006, the ceremony at Yu Tomb was listed as one of China's national intangible heritage properties. Since 2007, a major national commemorative ceremony has been held at Yu Tomb and the newly created forecourt.[Fig. 4] This ceremony was designed by Shao Zhongkai 邵仲凯, a director who has worked with the Zhejiang provincial Song and Dance Troupe. Lasting for fourty-five minutes, the order of service is as following:

- Standing at attention in silence.

- Nine beats of a drum to signify that the Great Yu quieted the waters of the Nine Prefectures (Jiuzhou 九州).

- Presentation of offerings by male officants wearing clothing embroidered with dragons and leather skirts. The offerings consist of: the Three Animals (Bull, Sheep and Goose—the traditional Pig having been replaced out of sensitivity for Muslim Chinese); the Five Crops, or cereals (rice, wheat, proso millet, foxtail millet and soybeans); and, the Five Fruits (local produce).

- Offering of incense.

- Beating of drums and bells. The drums have thirty-four faces representing the thirty-four provinces, municipalities, autonomous regions and special administrative regions of the People's Republic. A bell is struck thirteen times a figure that represents the 1.3 billion descendants of the Yellow Emperor.

- Playing of music, three orchestras perform: ancient bronze bells (bianzhong 编钟), traditional musical instruments and a western percussion band.

- Presentation of wine (local Shaoxing rice wine, the brand being 100 year-old rice wine of Dragon Mountain of the Ancient State of Yue 古越龙山百年陈酿黄酒).

- Offering of wine.

- Reading of the offertory prayer. This doggerel text includes reference to contemporary political policies in a mixture of semi-literary and demotic Chinese, these lines are highlighted in red:

Fig. 5 Stele at the Yu Temple. Photo: GRB.

- Participants and audience bow.

- Singing of a hymn of praise (two hundred people since 'Paean to Great Yu').

- A dance performance presented as an offering.

- Formal conclusion of the ceremony with streamers and fireworks.[Fig. 5]

The Making and Marketing of Remembrance

Zhu Yuangui 朱元桂 was the associate director of the first local public ceremony (gongji 公祭) at the Yu Tomb. He is the head of the Cultural Policy Research Unit with the Shaoxing Municipal People's Consultative Congress. He was in charge of the ritual aspects of the ceremony:

Fig. 6 The rebuilt main hall at the Yu Temple. Photo: GRB.

I was in charge of organizing the order of events for the ceremony as well as the offerings, vessels, offertory tables, the incense burners and the kinds of bells and drums used during it. Our task did not end with creating a respectful solemn atmosphere, we also wanted to do something that was a spectacle, attractive to tourists, a ceremony that would contribute to the development of tourism in Shaoxing. People would claim that we were just repeating a ceremony to commemorate the Great Yu that has been in use for 4,000 years. That's what you tell the tourists, the reality is somewhat different. We don't know how they commemorated Great Yu in the distant past. We followed [the Mao-era principle of] 'winnowing out the old and encouraging the new' (tui chen chu xin 推陈出新)… For example, out of respect for the Muslims, who are part of our Chinese nation, we replaced the pig used as an offering in traditional ceremonies with a goose. Our local ceremony established the framework and contents for what has now become the national ceremony (guoji 国祭).

Another local official who did not wish to be named offered the following comment on the business plan followed for the national ceremony:

Fig. 7 A fresco in the rebuilt main hall featuring the Great Yu. Photo: GRB.

In the lead up to the first public commemoration we had no idea how to budget for it. We decided we needed guidance so we asked the people at Huang Ling county how much they spent commemorating the Yellow Emperor (Huang Di 黄帝). They told us that, all up, they paid eight million yuan. We thought that was just too much: eight million for a ceremony that didn't even last an hour! But then we calculated that this activity would strengthen our ties to the central government and would have a flow-on effect on tourism, as well as enhancing our united front work with our Hong Kong and Macao compatriots, not to mention being able to attract investment to our area, so we put our minds to it. In the end, we far outspent that eight million and our budget was closer to fifteen million.

We went back to Huang Ling county and told them about the discrepancy and they said that was about right. They said: 'When we'd originally inquired we were too embarrassed to tell you the actual cost; we thought you might give up on the idea if you knew. You might also go around saying that we were wasting money.' They were right about the cost. Then, on the basis of what we'd done in 2005 we set about investing in the area so we could apply to be listed as an intangible cultural property, and for the right to perform the national ceremony. That cost 2.1 billion yuan. To perform this ceremony really does strengthen our relationship with the Centre. If we didn't have it there'd be no reason for Party-state leaders to come to Shaoxing any more. In the past, we had Lu Xun. Who's going to commemorate Lu Xun nowadays? When it comes to the Great Yu, even [former Party General Secretary] Jiang Zemin comes.

The Si Lineage 姒姓 and the Tomb of Yu

Fig. 8 The Republican-era Yu Temple and the rebuilt statue of the Great Yu. During the Cultural Revolution, the statue was beheaded. The head was then paraded through the streets of Shaoxing and ritually denounced. Photo: GRB.

Fig. 9 A photograph of the national ceremony to commemorate the Great Yu on display at the Republican-era Yu Temple. Photo: GRB.

Again, as we noted in March 2007:

Although various places in China have associations with Da Yu, it is Shaoxing that has come to be elevated to national status and, as outlined above, the veneration of Da Yu in that southern city indicates how different aspects of Da Yu are emphasised to appeal to different groups. There is an ongoing process in China for organised religions and governments to co-opt elements of folk religion for other purposes. According to some writers, Da Yu is the southern equivalent of Huangdi, the Yellow Emperor, but his role as a national progenitor is little emphasised at present, despite the existence of the primordial phallus (renzu) in Shaoxing. In genetic terms, he is remembered instead as a clan ancestor, although Yu, hailing from a mythic period when surnames had not acquired patriarchal significance, is variously claimed by the Si, Yu and Xia clans. The last of the three clan names is quite obviously an anachronism, unless Yu adopted the title of his own son.[Fig. 6]

In February 2007, the Si clan stole a march on the Yu and Xia clans by dint of better organisation. The deputy-director and secretary-general of the Shaoxing Si Clan Research Society, Si Daniu told reporters from Xinhua News Agency on 2 February that the society had determined to revive the ancient custom of sacrifices to Da Yu in the first lunar month, and that for thousands of years his clan had made sacrificial offerings to Da Yu both in the first lunar month and on the occasion of Da Yu's birthday in the sixth month. The clan can count on more than 200 family participants in this year's events, the first since the ceremonies at the Da Yu mausoleum were listed as a national intangible cultural heritage property by the central government.[Fig. 7]

The spokesman for the Si clan, whose observances honouring their ancestor ceased in the 1950s, also made it clear that the clan's sacrifices would fulfil the requirements of the tailao sacrifice and exceed them, by including three local types of tea and six local types of wine among the offerings.[Fig. 8]

According to our research in October 2009, the complaints of the Si Clan villagers cover the following issues:

Fig. 10 Pillars with the Republican-era Yu Temple in the background, formerly a pesticide factory. Photo: GRB.

- Yu Ling Village has been a natural village for thousands of years and the forced resettlement broke that continuity. 'We have lost our history', as one villager observed. 'Although we enjoy improved living conditions what's more valuable?'

- The Si Clan of Yu Ling Village are the direct descendants of the Great Yu and they can trace their ancestry back 4,000 years. 'We have our own ideas and methods for the protection and management of Yu Tomb. Why are our opinions ignored?'

- 'Since being relocated to Yu Tomb New Village we can no longer go to Yu Tomb freely. We are the descendants of the Great Yu, but now we have to buy an entry ticket to pay our respects to our own ancestor. It's ridiculous!'[Fig. 9]

- The authorities have said that in our new village we must be ready to welcome and entertain visitors, whether they are members of the clan returning to pay a visit or worshippers from afar. They say we have to open our doors to ticket-buying tourists and let them see us going about our daily lives. Can you call that a home?[Fig. 10]

In our future writing on this subject, more will be said about the fate of the Yu Temple during the Cultural Revolution era, the activities of the Si Clan and the views of Si Daniu, who is mentioned above, and the evolution of the new national ceremony in Shaoxing.