|

||||||||||

|

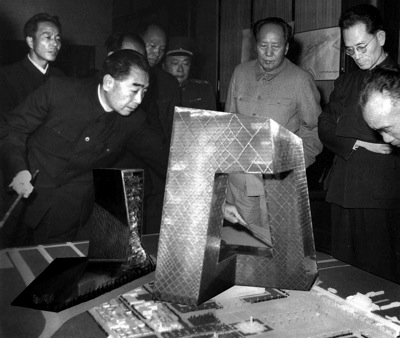

NEW SCHOLARSHIPRed Legacies in ChinaA Conference Report, Harvard University, 2-3 April 2010Jie Li 李洁 and Enhua Zhang 张恩华The two-day international conference ‘Red Legacy in China’ brought together scholars from North America, Asia, Europe and Australia to exchange perspectives on the lingering influences of the Chinese Communist Revolution as well as of other leftist currents in the contemporary era. The gathering was jointly sponsored by the Chiang Ching-Kuo Foundation Inter-University Center for Sinology, the Harvard-Yenching Institute and the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies.  Fig.1 ‘Red Legacy in China’ conference poster. The conference organizers posited a view of ‘red legacies’ that covered both the utopian ideals of revolution as well as its dystopian failures. They proposed that China’s red legacies manifest themselves in three broad ways: in the context of remnant traces of the Communist revolution and the socialist era, in contemporary representations and reinventions that evoke this past, as well as through ‘inherited’ and ongoing institutions, practices and mindsets. Associated with persons and artifacts, texts and sites, politics and capital as well as individual and collective memories, red legacies have been exerting an influence in various was in contemporary China: intellectual and mundane, spiritual and material, spatial and temporal, sociopolitical and commercial. The presentations at this conference sought to revisit, analyze and critique red legacies in contemporary Chinese culture and society. The conference began with opening remarks from William Kirby (Director of the Fairbank Center), Elizabeth Perry (Director of the Harvard-Yenching Institute) and David Wang 王德威 (Director of the CCK Foundation Inter-University Center for Sinological Studies). Apart from red legacies such as China’s national anthem and political education, Kirby pointed to non-existent red legacies such as monuments to the revolution’s victims and other ‘unconfronted, if not altogether uncontested, pasts’. Perry underlined the renewed attention on the lessons and legacies of the Chinese Revolution given China’s present economic ascendance engineered by a Communist Party that still celebrates its revolutionary origins. She emphasized that revolutionary legacies mean different things to people living in different conditions, so that it is important to be attentive to a variety of voices. In part to explain the apparent paradox of the Taiwan-based CCK Foundation co-sponsoring a conference on Red Legacy in China, David Wang mentioned that Chiang Ching-kuo himself spent four years in the Soviet Union, a fact that reflects the complexity of modern Chinese history, one in which red is just one of many colors in the broader spectrum of a shared past.  Fig.2 Huang Zhuan speaking to an image in his paper. The conference was organized into eight panels and roundtables, the first of which was ‘Red Foundations.’ In a paper entitled ‘Making a Revolutionary Monument’, Denise Ho 何若书 (University of Kentucky) drew on archival sources to reconstruct the official search in the 1950s for the site of the First National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in Shanghai, its various permutations and revisions to the exhibitions in the 1960s before the Cultural Revolution. Kaming Wu 胡嘉明 (Hong Kong Polytechnic University) presented a paper on the development of folk paper-cutting in contemporary Yan’an which has gone from being a household craft to become part of a more formal artistic and cultural heritage. ‘Building Big, With No Regret’, a paper presented by Zhu Tao 朱涛 (University of Hong Kong), explored the tradition of monumental architecture from Beijing’s ‘Ten Great Buildings’ project (1958-1959) to today’s mania for mega-buildings, demonstrating how the legacy of ‘building big’ with little regard for human and social costs has been transmogrified into a new hybrid form of monumental architectural practice in which revolutionary voluntarism is admixed with globalizing currents and capital. Felicity Lufkin (Harvard University) served as the panel’s discussant, raising in particular the implicit issue of the ‘foreign gaze’ in all three papers. The second panel ‘Red Classics Reread’ began with a presentation by Wang Yao 王尧 (Suzhou University) entitled ‘A Booklist and the Rise and Fall of “Red Classics”’, which chronicled the transformation of revolutionary fiction of the ‘seventeen years’ (1949-1966) from ‘red’ to ‘black’ during the Cultural Revolution as well as the canonization of these works since the 1980s. In her paper, ‘Castration and Incest for the People in Hao Ran’s Stories’, Xiaofei Tian 田晓菲 (Harvard University) re-read some short fiction by this popular writer of the Cultural Revolution period in search of cultural subtleties that work through inherited linguistic codes, rhetorical strategies, motifs and images designed to appeal to a broad readership. Tian argued that the more successful propaganda a work of art is, the more intricate the cultural negotiations at work tend to be. Catherine Yeh 叶凯蒂 (Boston University) examined issues of memory and trauma in two works of youth literature—Bi Ruxie 毕汝协’s underground novel The Tidal Wave 九级浪 (1970) and Wang Shuo 王朔’s Animal Fierce 动物凶猛 (1991; also translated as Wild Beasts), both of which deal with adolescence during the Cultural Revolution. Yeh traced the connections between the two novels in their narrative structures and literary tropes, which affected an entire generation’s memories of the Cultural Revolution. Alexander des Forges (University of Massachusetts, Boston) commented on these three takes on canonical ‘revolutionary’ fiction.  Fig.3 An image from Zhang Enhua’s paper. The Friday afternoon session ‘Red Performances’ began with a presentation by Han Zhao 赵涵 (Hendrix College) entitled ‘Sickness, Eggs, and Colors: Cui Jian’s Lyrical Negotiation with China’s Red Legacy’. Examining the rock musician Cui Jian’s 崔健 corpus produced from 1994, the paper contended that China’s revolutionary experience undergirded Cui’s thinking and that he appropriated the past to articulate concerns for the present, which are more social than political, more reactive than activist. Xiaomei Chen 陈小梅 (University of California, Davis) presented a paper on the revolutionary song-and-dance epics East is Red 东方红 (1964) and The Road to Restoration 复兴之路 (2009). While demonstrating the enduring power of revolutionary pageants, she argued, the more recent production also rewrites ‘red legends’ to celebrate capitalist reform by manipulating historical narratives, political orientations, celebrity and popular culture, as well as nationalistic sentiment. Finally, Yomi Braester (University of Washington, Seattle) presented on Cui Yongyuan’s 崔永元 canonization of Maoist cinema through 100 made-for TV documentaries, each telling the circumstances of a single film’s production and reception. Rather than call for nostalgia, outright condemnation, or even playful spoof, Cui takes on and shares with his audience the role of the amateur historian and cinephile. In her remarks as discussant, Claire Conceison (Duke University) called attention to the issues of spectatorship and reception that reach beyond the more limited practice of decoding text and analyzing visuality. The final session on Friday featured a roundtable devoted to ‘red historiographies’ that was chaired by Merle Goldman (Harvard University). Although invited to give a paper, Cui Weiping 崔卫平 (Beijing Film Academy) was denied permission to leave China. A message she sent to the conference was read on her behalf. In it she said that the authoritarian legacy of the Communist Party remains a part of the lived reality in China today. This was followed by a discussion of Cultural Revolution rebels by Guobin Yang 杨国斌 (Barnard College), who pointed out that the commodified legacy of the Cultural Revolution masks the alternative legacy of rebellion, which was not in and of itself responsible for violence, but rather a legitimate response to political repression as well as being a meaningful challenge to bureaucratic power. Xueping Zhong 钟雪萍 (Tufts University) spoke about New Left critical thinking in contemporary China, which uses Chinese revolutionary and socialist legacies to question the hegemonic ideas and values that have been dominant during the last three decades of economic reforms and socio-cultural changes. Li Ling 李玲 (Beijing Language and Culture University) presented a paper on the changing assessments of Deng Tuo 邓拓 in the post-Mao era. With a new reading of Xie Jin’s 谢晋 1986 film Hibiscus Town (Furong Zhen 芙蓉镇), Xudong Zhang 张旭东 (New York University) aimed to show the structural and philosophical overlap between revolutionary and post-revolutionary ideologies and their life-and-death rivalry in claiming what is “right” for the country and the people. Xiaobing Tang 唐小兵 (University of Michigan) contended that the quintessential socialist mass cultural form is the public poster, the counterpart of commercial advertisement in commodity cultures, and that both serve to change perceptions, to introduce desires and to project ideals of what life should be like. At the Saturday morning panel on ‘red art’, Harriet Evans (University of Westminster) presented a paper on images of women in posters of the Mao era, commonly associated with the slogan ‘women can do whatever men can do’. Through interviews with artists and close-readings of the posters, Evans detected ambiguities of meaning between slogan, image, intention and reception that went beyond ideological constraints governing the posters’ form and content. In a paper entitled ‘Love’s Labor’s Lost: Time for a Requiem for Socialism’, Eugene Wang 汪跃进 (Harvard University) explored artistic responses to the landslide change from socialism to post-socialism through the issue of labor. He argued that nostalgia for the glorification of labor under socialism is now displaced into some disembodied forms of experimental art, where labor is still valorized, although in sublimated ways. Andy Rodekohr (Harvard University) explored the afterlife of the crowd image following the Cultural Revolution, drawing a specific link between pervasive images of crowds in propaganda posters of the revolutionary era with the maximalist techniques of post-revolutionary China. The panel concluded with a presentation on the curatorial concept of ‘state legacy’ (guojia yichan 国家遗产) by Huang Zhuan 黄专 (Guangzhou Art Academy), who deplored the lack of independent political thought in Chinese contemporary art. Instead of cynicism and parody, he called for a neutral, ‘extra-ideological’, and critical reflection on ‘state consciousness’ through material artifacts, political spaces, cultural ceremonies, and aesthetic activities. Xiaobing Tang discussed these papers in relation to four ingrained Socialist concepts: (repressed) pleasure; labor; crowd (or communities and collectivities); and, the state.  Fig.4 An image from Zhu Tao’s paper. For the next session on ‘Red Memory Landscapes’, Kirk Denton (Ohio State University) and Enhua Zhang (University of Massachusetts, Amherst) discussed the emerging phenomenon of ‘red tourism’ in China, promoted by the central and local governments since the early 2000s as a response to the decline of socialist memory in the market reform era and as a way to stimulate the economies of these (generally) backward regions. Treating red tourism as a new form of patriotic education as well as commodified nostalgia, Denton first offered some background on the history of revolutionary tourism and then provided anthropological description of how Chinese tourists experience and participate in red tourism, with Jinggangshan 井冈山 and Shaoshan 韶山 as case studies. Prefacing her talk with a video clip of a recent trip to Shaoshan, Zhang emphasized the way red tourism in practice deviates from its stated goals of socialist education to the vulgarization of revolutionary history and the promotion of local official corruption, such as tourism with public funds and unequal distribution of tourist revenues. Beginning with a genealogy of the Cultural Revolution Museum concept, Jie Li (Harvard University) examined some existing museums and memorials of the Maoist era, among them the Jianchuan Museum ‘Red Age’ series 建川博物馆红色年代系列 in Sichuan and the ruins of Jiabiangou 夹边沟 labor reform camp. Emphasizing the commemoration of the revolution’s human costs, Li went on to propose the idea that local memorial projects could intermingle sympathetic identification with critical reflection. In what was to have been a discussion of the three papers, Elizabeth Perry (Harvard University) presented her perspectives on red tourism in today’s coal-mining town of Anyuan 安源. The Saturday afternoon panel ‘Red Dreams, Red Dust’ began with Chen Fangming’s 陈芳明 paper on ‘Ye Shitao 葉石濤 and Chen Yingzhen 陳映真: Two Aspects of Leftist Fiction in 1980s Taiwan’. While seemingly representing two extremes of the ideological spectrum—Ye being pro-independence whereas Chen being pro-reunification—the two writers’ literary careers both bear historical scars from the authoritarian era and critique the capitalist transformation of Taiwan. Letty Chen 陈绫琪 (University of Washington, St. Louis) discussed Chinese expatriate memoirs of the Cultural Revolution. Using Jung Chang’s 张戎 popular Wild Swans 鸿 as a case in point, Chen argued that such writings of victimhood play on the authenticity of suffering to facilitate the diasporic writer-individual in her formation of a new socio-cultural identity in the West. The concluding paper from Geremie Barmé, entitled ‘Red Allure and the Crimson Blindfold’, critiqued the ‘abiding, and beguiling, heritage of the high-Maoist era and state socialism.’ He argued that the origins and evolution of what would become High Maoism from the 1950s must be located in cultural and political genealogies of the Republican era. In his remarks as discussant, David Wang (Harvard University) reminded scholars also to engage with the ramifications of revolutionary legacies in peripheries beyond Mainland China, including Malaysia, Hong Kong and Taiwan. The final roundtable, chaired by Roderick MacFarquhar (Harvard University), featured general reflections on the subject of the conference. Hue-Tam Ho Tai gave a comparative perspective of remembering the war dead from Vietnam, where private families created places of memory apart from that of the state. Rudolf Wagner (University of Heidelberg) spoke of the possible benefits of having a master-narrative that prevents the eruption of social conflicts. Carma Hinton (George Mason University) provided personal reflections on reconciliations between teachers and students in the wake of the Cultural Revolution as well as discussed the need to attend to the complexities of that historical era beyond apotheosis and demonization. Eileen Chow 周成荫 (Harvard University) presented on the phenomenon of ‘white tourism’ in Taiwan, where sites associated with Chiang Kai-shek have become attractions for Mainland Chinese tourists. Wang Hui 汪晖 (Tsinghua University) argued that the Chinese revolution is a thorough social mobilization that should be distinguished from that of Soviet bloc. Elizabeth Perry asked for considering the cultural resources China deployed in order to maintain regime continuity. Interventions enlivened the discussion and challenged some of the comfortable assumptions held by various scholars. The two-day conference attracted an audience of about two hundred people. The full list of speakers and the abstracts their papers can be found on the conference website. A volume of essays generated by the conference is under preparation. |