|

||||||||||

|

NEW SCHOLARSHIPGhulja in 1912: A Chronicle from the Russian Muslim PressIntroduced, translated and annotated by David Brophy Postdoctoral Fellow, Australian Centre on China in the World, The Australian National University

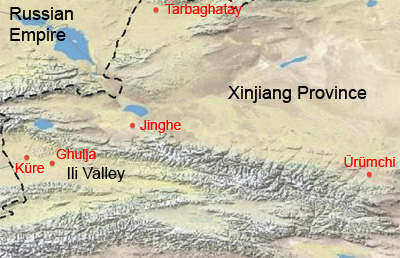

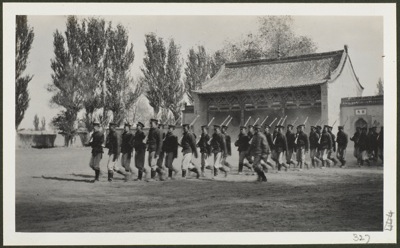

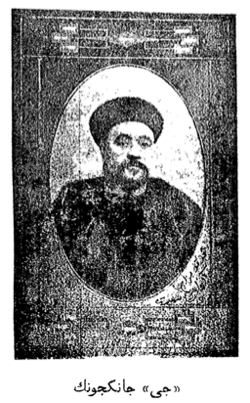

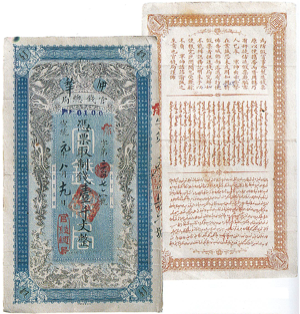

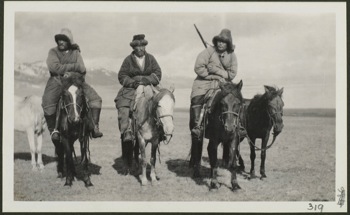

The Xinhai Revolution was not a single event, but rather a process that played itself out in ways that were as diverse as the population and geography of the soon-to-be defunct Manchu-Qing empire itself. In many places in the north, abortive revolutionary uprisings were suppressed, and only with the abdication of the emperor and Yuan Shikai's proclamation of the Republic of China did holdout officials grudgingly fall into line. Such was the case in Ürümchi, centre of the civil administration of Xinjiang province. To its west in Ili, on the other hand, a concentration of revolutionaries from Hubei province were able to take power and declare their loyalty to the new Republic, holding out against military expeditions dispatched from Ürümchi in the crucial early months of 1912.  Fig.1 Map of the Ili valley The Ili Valley was, as it is to this day, home to a wide variety of peoples, some such as the Kazakhs and Uyghurs who claim indigeneity, but also many recent arrivals. In the eighteenth century, the Qing occupation saw first Manchu, Chahar Mongol, Sibe, Solon and Daghur communities sent from Manchuria to garrison the new frontier. The nineteenth century witnessed a steady flow of Han Chinese and Hui Muslim migrants, and the opening of trade with Russia from the 1850s swelled the population of Russian subjects, mostly Turkistani and Tatar traders. These well-travelled Silk Road entrepreneurs linked Ili, and in particular the largely Muslim town of Ghulja (Ningyuan 寧遠; now Yining 伊寧), to a Turkophone print culture founded on the intellectual centres of Russian Muslim life on the Volga and the Siberian steppe, places such as Kazan, Ufa, and Orenburg. Pioneered since the middle of the nineteenth century, by the early twentieth century editorial offices in these cities were publishing daily newspapers and weekly journals with large networks of contributors and readers, including among the Muslims of Xinjiang, who could subscribe through the Imperial Russian postal service, or obtain copies brought by trading caravans.  Fig.2 Time front-page banner At the turn of the century, in the face of Slavic dominance Russian Muslim intellectuals keenly felt the need to develop their own communal resources. Periodicals stood as symbols of cultural strength. Tatars living in Xinjiang frequently expressed a belief that growing Russian strength on China's doorstep might doom China to a colonial fate similar to their own. Hence they identified strongly with the growth of modernising forces in China, and welcomed the Xinhai Revolution of 1911-12. In the collapse of dynastic rule in China they saw a possible harbinger of Tsarism's own decline. The Orenburg daily Time (Vaqıt Вакит) not only translated and reprinted news on the Xinhai Revolution from Russian sources, but published dispatches by three men living in Ghulja at that time. Twelve of these dispatches are offered here in English translation. These articles are a valuable source on the history of the Xinhai period in Xinjiang; they add detail and perspective to a story that is itself not well known. They also impart something of the complexity of political life on this particular edge of the Chinese-speaking world. They describe; a revolt led by anti-Manchu Han revolutionaries leading to the installation of a Manchu at the head of the new regime; the fissiparous tendencies of local Kazakh and Mongol groups; and, the looming presence of the Russians and the Cossack guards, ready to intervene should events take a turn contrary to their interests. While local Muslims were, unsurprisingly, wary of the rising tide of Chinese nationalism, for contributors to Time such hesitancy was a symptom of backwardness, and they berate local Muslims for failing to take advantage of the new political situation. This dual nature of Chinese nationalism—an inspiration to outsiders, but a source of anxiety for non-Chinese such as Uyghurs or Mongols within the former empire—was to remain a feature of China's presence in world politics throughout the twentieth century. My annotations to the texts are marked by square brackets []. Where possible I have identified names, places, and titles by adding Chinese characters to the original. In those cases where individuals are otherwise unknown to me it should be kept in mind that the Arabic script does not allow for an unambiguous rendering of Chinese syllables; my reconstruction of some names could well contain errors (e.g., Mu may well be Mao). Note also that dates in the articles follow the Russian Julian calendar. I have provided the Gregorian equivalents. The translations are followed by a link to the original texts. I am grateful to the editor of China Heritage Quarterly for his suggested revisions of the draft translations. G.E. Morrison, the Australian journalist, sojourned in Ghulja in 1910 while on his epic ride from Beijing to Russian Turkistan. Thanks to the Mitchell Library in Sydney, I have been able to provide a few of his photographs to accompany the articles. For more on Morrison in the years surrounding the Xinhai Revolution, see Linda Jaivin's 'Morrison's World', the Seventy-second George E. Morrison Lecture, presented at ANU on 13 July 2011, the text of which is also available in this issue of China Heritage Quarterly.—David Brophy Events in Ili Province, 4 February 1912After the Chinese revolution had consolidated itself in the regions of Hankou, Henan, Wuhan and elsewhere, a branch of it reached our province of Ili [i.e., Turkistan under Chinese rule].  Fig.3 Yang Zuanxu 楊纘緒 (Yang Tongling in the text). (Photograph: courtesy of Xue Er 雪珥) The centre of the administration in Ili province is Küre [Ch: 惠遠 Huiyuan]. Two or three months previously an official named Zhi [志銳 Zhirui] came as jiangjun 將軍 (Military Governor). This man was a Manchu, and a defender of the old ways. Upon his arrival he closed down the jadid [new-method Islamic] schools, saying that they were 'nests of rebellion' and, since Chaghan [the new year celebration on 22 December 1911], he has sent the Qalmaq[1] and Sibe troops back to their homes, saying to them that he would tell them when to report for duty. However, Yang Tongling[2] 楊統領 (the leading army officer here) maintained some three hundred and fifty personal troops, all Chinese by race. The Jiangjun didn't dare dismiss these. Yang Tongling himself belongs to the Chinese race, and he has received European-style training. Not long afterward, conflict erupted between Yang Tongling and the Jiangjun. Eventually, on 25 December [7 January 1912], at around eight or nine in the evening, Yang Tongling invested the city with his forces and bombarded the Military Governor's office. The Governor fled with his family and hid until dawn. He was found nonetheless, dragged into the street and shot. When the uprising broke out, no one could get in or out of the city because the gates were shut. Afterwards, the rebels sacked the offices of the Governor and other high officials and set fire to them. They took [the officials] prisoner. When the rebels had established control over the populace they announced that they would govern the Ili Province as a republic, under a da dudu 大都督,[3] and they appointed Guang [廣福 Guangfu], who had been governor before Zhi, to head the government. At present the province of Ili is being administered as a republic. Yang Tongling was the Editor-in-Chief of the Ili Provincial News [Yili baihua bao 伊犁白話報]. Our readers may recall that this paper was also published in a Turki edition. Kh[udayberdi]. Q[ulja]. Kh. Q., 'Ile vilāyeti vāqıʿaları', Vaqıt, 22 January 1912, p.3. Notes:[1] Consistent with long-standing usage in Turkistan and Russia, the author uses the word 'Qalmaq' here to refer to Mongols. It is the same word as 'Kalmyk', the Mongolian nationality who occupy the Republic of Kalmykia on the shores of the Caspian sea. [2] Yang Zuanxu 楊纘緒 was, appropriately, a native of Wuchang 武昌, Hubei province, and graduate of a Japanese military academy. In 1908, while working as a military instructor in the Hubei New Army, he and his unit were transferred to Ili. [3] Dudu, and da dudu, are ancient military titles denoting supreme command. They had been in use since the Han Dynasty but, phased out in the early Qing they were superseded by the Manchu banner hierarchies. The title dudu was revived during the Xinhai year and the first years of the Republic when it was used to denote provincial military chiefs. Eventually it was replaced by the title dujun 督軍. Events in Ili Province, 23 February 1912Two or three months ago Zhi Jiangjun came from Beijing to the town of Küre, which is the centre of Ili province. After his arrival a dispute erupted between him and Yang Tongling [Yang Zuanxu 杨缵续]. The Jiangjun is a supporter of the government, and belongs to the Manchu race. As for Yang Tongling, he belongs to the Revolutionary Party (Gemingdang 革命黨) and is Chinese by origin, and he has studied in Europe. Yang Tongling himself came three or four years ago from the direction of Beijing. He had three hundred and fifty soldiers of his own kind. After Zhi Jiangjun arrived, he failed to disperse monthly salaries to Yang's troops, and became directly hostile towards Yang. Conflict developed between them. On 8 December [21 December] the Jiangjun dismissed a number of Sibe, Solon and Qalmaq soldiers and instructed them to return in the new year.  Fig.4 New Army soldiers drilling in Küre. (Photograph: G.E. Morrison; courtesy of Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW [a1788097]) After the dispute arose, Yang Tongling was granted permission by the Jiangjun to visit Beijing. He met with the Russian consul in Ghulja and had him issue a pass allowing him to journey through Russia as well as receiving letters for the Governor-General of Tashkent and the Russian Consul in Harbin. Thereupon he then departed for Küre. After Yang Tongling returned to Küre, the soldiers who had come with him found out that he had been given leave for his trip, and they remonstrated with him: 'Set our affairs in order before you leave. We haven't been paid for three or four months now. We placed our trust in you by coming here. If you leave now, we will starve to death!' Yang Tongling responded: 'Very well, if you are willing to obey my orders, I will give not abandon you.' The soldiers were satisfied, and they swore loyalty to Yang. On the evening of 25 December [7 January 1912] around nine o'clock, Yang Tongling had his soldiers placed two guns outside the Jiangjun's yamen and shot fireworks.[1] Afterwards, Yang fired his own gun twice. Then they took aim at the Jiangjun's house and fired. At the sound of fireworks, gunfire and the cannon, the Jiangjun, his wives, and his servants fled outside. The guards of the Jiangjun's yamen returned fire. The Jiangjun, his wife's coachman Hasan (a Russian-subject Tatar) and other employees fled into the Sibe and Solon neighbourhoods. They hid there until dawn. As dawn approached Hasan apparently went to the Jiangjun and told him he could spirit him away to a place where he couldn't be found. Since escape proved to be impossible, they hid him in some hay. The shooting continued until ten o'clock midday on 26 December [8 January 1912]. Yang Tongling was probably only shooting to scare people since his guns and cannons were firing blanks. All the reserve cartridges and fuses were in the hands of the Sibe and Solon, who were on the side of the Jiangjun. The Sibe and Solon were trying to keep control of the arsenal, and when they started to fire more fiercely, Yang's supporters too replied with real ammunition. During the fighting, Guang Jiangjun (Guang is a Manchu Jiangjun who preceded Zhi) went to where the firing was coming and said to Yang Tongling: 'Stop firing! There is no use in shooting, it will only hurt both sides. We must resolve this conflict through negotiation. I am willing to act as an intermediary in peace talks.' Yang Tongling ordered his supporters to cease fire and, when this side stopped, the Sibe and Solon side also stopped shooting. Guang Jiangjun summoned Meng Galai Da, and the meyen (government officials who manage the affairs of the Sibe and Solon), and encouraged them to make peace with Yang. They also made the Sibe and Solon hand over their weapons and surrender.[2] On the night of 25 December, about forty of Yang Tongling's soldiers went to Mu Amban's house (a government official who supervised the affairs of the Kazakhs and Qalmaqs), forced the door open and demanded to see Mu. They were told that he had gone with his wife and children to join Guang Jiangjun. Apparently the soldiers made to strip the house, but their officers prevented them from doing so. Instead, they set fire to the place before leaving. Amidst the conflagration Manchus rushed in and stole the furniture. [By this time] Mu Amban had taken refuge with his family in a storehouse attached to the house and had locked the door. Once the house caught fire, one of his Kazakh subordinates informed Wang Luzong (the officially-appointed company director of the Leather and Wool Company).[3] who sent someone to batter down the doors and spirit the amban and his family away to the yamen. At one o'clock on the day of 26 December [8 January 1912], Yang Tongling's soldiers found Zhi Jiangjun in the hay and brought him to the 'chanfuzul' (treasury).[4] Soldiers held both of his arms while another shot him from behind. Meanwhile, Guang had summoned Yang Tongling and the government supporters to the Duma [дума, i.e., municipal assembly] to begin peace negotiations. Yang Tongling had his men look for the government officials who were in hiding and bring them to the Duma. They also found Mu Amban in his hiding place and took him to the Duma. Guang Jiangjun met with Yang Tongling, Meng Galai Da, Bao Amban and He Daren at the Duma and explained what he knew of the events. These officials requested that Yang pardon Fu Galai Da[5] and Tomachi Ghaldamin (a government official). Yang accepted these petitions and forgave them. After that, the officials jointly requested that he also pardon Zhi Jiangjun. Yang Tongling apparently forgave him too, but before it was announced to the soldiers Zhi had already been killed. After Zhi's death, his senior wife had fainted and expired, but his second and youngest wives survived. They were spared. The jiangjun's assistant dutong 都統 was wounded during the evening mêlée. The respective yamen of the jiangjun, dutong, as well as that of Meng Galai Da, and Mu Amban's house, had been razed. The treasury and the Leather and Wool Company were seized were now under military guard. During these events five men died on Yang Tongling's side, and on the side of the government the jiangjun, his son and his hiya (a lower-level secretary), and a total of twenty Sibe and Solon were killed. On 27 December [9 January 1912] General Guang was made da dudu. Other officials have yet to be appointed. Henceforth, all titles such as jiangjun, dutong, daotai 道台, zhifu 知府, meyen amban and xianguan 縣官 are to be abolished, and a new administration appointed. The bazaars and areas around Küre, Suidun and Ghulja are completely safe. No harm was done to the traders in the fort of Küre. The da dudu has apparently sent a letter in the name of the government announcing that he intends to deal with the Russian Consul in accordance with previous agreements. The Consul said that he could not accept this without the permission of his government, so he returned the proclamation, and sent telegrams to Saint Petersburg and Beijing explaining the situation. They say that a reply came stating that if [the new government] maintained neighbourly relations as before, [the Consul] should accept its proclamations. If there are infringements, however, he should make this known. The da dudu is said to be busy preparing a constitution for Ili Province. It will probably be promulgated soon. Notes:[1] The author uses the word pujang < Ch.: paozhang 炮仗 'firecrackers'. [2] Manchu galai da, Ch.: yizhang 翼長 'brigadier'; meyen here is short for Manchu meyen amban, Ch.: lingdui dachen 領隊大臣. Meng Galai Da is the Manchu official Meng-ku-tai 蒙庫泰, an official of the Plain Blue Banner of the New Manchu Battalion, the main unit that resisted the uprising. [3] The Ghulja Leather and Wool Company (Pimao Gongsi 皮毛公司), founded in 1905 on the initiative of the Ili General, was one of Xinjiang's first joint-stock companies, with shares held by private investors and local officials. [4] A loanword from Chinese chanfuzul derives from qianpuzi 錢鋪子 'banking house', cf. Uyghur ashpuzul < ash 'food' + puzul < 鋪子. [5] Either the Sibe official Fu-le-hu-lun 富勒祜倫, or the Solon Fushan 福善.  Fig.5 M[ansur] Sh[eykhof] (Ghulja). M. Š. (Ğulja), 'Ile vilāyeti vāqıʿaları', Vaqıt, 26 February 1912, p.2. Events in Ili Province, 10 March 1912Those who initiated the uprising here and who are its primary inspiration are young Chinese officers who studied abroad. Their leader is Yang Tongling, a graduate of a Japanese military academy. According to the most conservative reckoning Muslims make up three quarters of the population. Yet they are absent from the conflict and they have not made any moves. They regard the uprising as if it was a war in a foreign country, or a fictional tale. They continue to chat and gossip as before. Although there are a few among them who follow the Chinese around, it is not in accord with any principle, but simply because they feel that as a result of this uprising they might obtain some office. The future of the uprising, and whether or not the new administration will be beneficial or detrimental for the Muslims, is still unclear. The courts and bureaux of the new administration are being put into order. Although with the passage of time, [Muslims] may benefit from changed social and political conditions, this is but a distant possibility. This is because they are completely ignorant of the affairs of the world; they are still a long way far from understanding the implications of changes to the country's administration, of autocracy and freedom, and a knowledge of how to adapt themselves to these and benefit from them. They pass their lives believing in superstition and fables. On account of this, even if a republic is established in China, it is highly doubtful that the Muslims here will benefit from it. Events in Ili Province, 19 March 1912The uprising continues. There is news that the rebels have taken Xihu 西湖, which was held by Ürümchi. Wounded soldiers have begun to return. Those returning from battle say: 'Government troops from Ürümchi far outnumber the rebels. The rebels pushed ahead despite all kinds of obstacles. They have killed thousands.'' It is only natural that Russia will look to its own interests here and keep a careful eye on developments. Up until now they have not interfered; to all appearances they remain neutral. The Russian Consulate was planning to bring in troops in order to protect its own subjects. However, as yet this has not happened; it would appear that they have not thought it necessary as the fighting has been at such a distance. The Consulate maintains a permanent guard of fifty mounted soldiers. There is no sign of movement among the Muslims here. They lie still, saying 'whoever takes my mother as wife will be my father'. Rumours that the Kashgari Muslims have appointed a khan from their own number were spread to uncertainty among Chinese in the interior. The idle words that are encountered in The New Times [Novoe Vremia/ Новое Время—a Russian daily], that 'one witnesses here the idea of pan-Islamic unity; its propagation is aimed at stirring up the Muslims' are pure falsehood. The fact that the Muslims here have neither the inclination nor knowledge to do such things is proof positive of the inaccuracy of such reports. M[ansur] Sh[eykhof] (Ghulja). M. Š. (Ğulja), 'Ile vilāyeti vāqıʿaları', Vaqıt, 6 March 1912, p.2. Events in Ili Province 29 March 1912 Fig.6 Portrait of Zhirui 志銳 from the pages of Time What Zhi Jiangjun, a member of the ruling Manchu dynasty,[1] did when he came to Ili province as was to abrogate the reforms introduced by the previous governor Guang and the head of the military, Yang Tongling. During the time of Guang Jiangjun new-style schools (xuetang 學堂; maktab) had been opened in the cities as well as in some of the villages. Zhi closed them, saying that these would become nests of rebellion, that people do not need literacy, since if they learn to read they will start to disobey the government. Previously in the cities municipal Dumas had been opened, with members elected from each community (Taranchi, Kashgari, Dungan and Chinese) in accordance with their size. Their role was to resolve disputes among the traders, and work on reforms in the city. Zhi closed the Duma as well. The reason he gave was that if people were to manage their own affairs then they would no longer pay attention to government officials. During Zhi Jiangjun's serving in Ili as an official with the rank of daren in the five or so years prior to this, he tyrannised the people of Ili, and for this reason people throughout the province were concerned when he was promoted to jiangjun. Yang Tongling (who now stands at the head of the republican troops fighting against the supporters of the old) is an ordinary Chinese who was born and educated in Hubei. Afterwards, in order to broaden his learning, he travelled to Japan where he increased his understanding of the military. He then returned to his native Hubei and took up service in the army. He was later appointed to Ili as an officer with the rank of tongling. He has been exerting himself to the utmost for the propagation of education in China. When the Revolutionary Party organised an uprising against the government on 25 December in the city of Küre, which is the centre of Ili province, they bombarded Zhi Jiangjun's yamen with cannon. At that time, the Jiangjun had money there worth 100 to 150,000 roubles. Although they took a lot of it after the fire started, it was consumed in the flames. Singed notes have now begun to appear in the bazaar. However, the merchants won't accept them since they are worried that the banks where they live won't recognize them. Following the uprising Chinese started depositing the money they had previously kept at homes in the Russo-Asiatic Bank in Ghulja. Asians too had the habit of burying their money in the ground or storing it with foodstuffs. That custom may now be coming to an end. In the Chinese state there are a total of twenty provinces and to date the revolutionaries have taken fourteen of them, including Ili. It appears that henceforth five provinces will be autonomous. Only four provinces are left to the Manchu government. In Chinese Turkistan the centre of the province called Xinjiang is Ürümchi. Other noteworthy places in this province are: Ghulja, Suiding, Kashgar, Khotan, Yarkand, Qarghaliq, Aqsu, Kucha, Korla, Qarashahr, Toqsun, Turfan, Qumul [Hami], Barköl, Chöchäk and Manas. In each province there is one xunfu 巡撫 and two or three daotai (vice-governors). Each daotai has two or three zhifu beneath him, and each zhifu three or four xianguan (county officials). In China the civil administration is organised thus: the first rank is the xunfu, the second rank is fantai, third is daotai, fourth zhifu and fifth xianguan. As for the military, the first rank is dashuai 大帥, commander of all the troops in a province; then zongtong 總統, in charge of the troops of more than four provinces; then tongling, in charge of more than one province's troops, [equivalent to] the rank of general. There is also the daren who is in charge of more than five hundred soldiers, [equivalent to] the rank of colonel. The officials who supervise the nomadic peoples and the Manchus, and officials involved in other affairs, are always drawn from the Manchus. These are not appointed in order to carry out any particular task, rather they are appointed simply to exploit the people. They themselves spend a lot of money to obtain a position. The first rank is jiangjun, the second rank is meyen amban, and the third is galai da. [Xinjiang] province has not completely gone over to the revolutionaries yet. This is because the provincial head, the xunfu, is not inclined to give in. From the other towns the response has been that they will support whichever side the xunfu submits to. The daotai and xianguan of Ghulja have resigned their positions and moved into quarters in the Russian neighbourhood. In place of the daotai and xianguan new officials were appointed by the authority of the da dudu.  Fig.7 Local Ili currency, 1910. (Source: Zhu Yanjie, et al., eds, Xinjiang qianbi 新疆钱币, Ürümchi: Xinjiang Meishu Sheying Chubanshe and Hong Kong: Xianggang Wenhua Jiaoyu Chubanshe, 1991, p.112.) On 30 December [12 January 1912] in the city of Ghulja the flags of the da dudu were raised. The flag is white, in the middle is a symbol of a sun in red, and around it are stars. In the middle of the sun there is something written in Chinese. Apparently these words translate to 'a light is born unto the nation'.[2] The new government is now said to have divided its troops into ten or twelve divisions. They are continuing to increase the number. For the infantry the monthly salary is twelve taels, and if the soldier has his own horse it is twenty-four taels (this is the equivalent of six and twelve Russian roubles respectively). The government provides money for clothing and food. To clothe its troops the regime of the da dudu awarded a contract for 4000 cloaks and 4000 pairs of leather pants to the company of Husayn Musabayev and Brothers, with the stipulation that they are must deliver these goods within fifteen to twenty days. They also ordered 400 Cossack saddles from the same company. Because of the uprising in the province of Ili, the exchange rate of the Russian rouble rose. At first one rouble was worth one tael ninety-seven fen Chinese currency. Now it has risen to two taels and thirty fen. This is because Chinese merchants are fearful and are exchanging their money for roubles and putting it in the bank. The bank does not accept Chinese currency. Notes:[1] Zhirui was the cousin of two of the Guangxu Emepror's concubines, his favourite Zhen Fei 珍妃 (best known as the concubine supposed to have been cast into a well at Cixi's command) and Jin Fei 瑾妃. On the link between Zhirui's fortunes and those of his cousins, see the recent article by Xue Er 雪珥: 'Uncle of the Empire Ashamed to Look at himself in the Mirror' (Guojiu toulu xiu duijing 国舅头颅羞对镜), online at: http://nf.nfdaily.cn/nfdsb/content/2011-07/07/content_26491127.htm. [2] More than likely the Xinhai watchword guangfu 光復 'revive the light', a rallying cry of anti-Qing societies and deployed by revolutionaries post-1911 to refer to the victorious uprising, similar to the way in which jiefang refers to the 1949 revolution. (The 1945 end of Japanese colonial rule on Taiwan is also referred to as guangfu; and post-1949 Taiwan-based KMT efforts to retake the mainland were also spoken of as attempting to guangfu dalu 光復大陸. For more on guangfu see the Glossary in this issue.[LINK]) Events in Ili Province, 3 May 1912A decree issued by the provisional republic has arrived. Translated into Turki it has been circulated among the people, most of whom have reacted favourably. The document announces Yuan Shikai's election as President and details regarding the Preferential Policies towards the emperor. It calls for unity and solidarity and promises that subjects of China would enjoy the same rights regardless of ethnicity, race, or religion. According to the decree, the emperor has not entirely abdicated from the throne, and while Yuan Shikai is titular President of the Republic, in truth he will hold an office similar to Turkey's Grand Vezir [ṣadr-i aʿẓam], and China will not be governed as a republic, but as something resembling a constitutional monarchy.[1] In fact, there are even doubts about this, as historical precedents indicate. Among its population of four or five million, there may be a few outstanding individuals familiar with how governments are run in developed countries; they are capable of administering the Chinese state in conformity with these, of leading the homeland and the nation towards civilisation, and who are willing to sacrifice themselves and what they own to attain enlightenment. However, for every one such champion there are inevitably a hundred recalcitrants. The country is vast, there is no railway or telegraph lines linking the provinces. Communication between Ghulja and Beijing is via Russia; there is no direct route. The situation is the same in other regions. When the flag of freedom and republicanism is raised in one place, the monarchists there employ all kinds of tactics in response. For example, the Republic has now been proclaimed in Beijing, but the fighting is going on here between those on the side of the government, i.e., those in Ürümchi, and the revolutionaries. When a warning comes from Beijing that 'the Republic has been established here, all fighting must cease for it is futile', but they reply that 'we are not resisting the Republic, we are doing battle with local bandits'. In summation we can say that we have witnessed the fact that republicanism has often foundered in other countries because it has not been grounded in constitutional government. Now, for a people who had faith that happiness lay in the old ways and in whose blood those ways continue to course it will not be easy for them to abandon the old in favour of a republic. Should they be successful, despite both custom and nature, they will go down in history. M[ansur] Sh[eykhof] (Ğulja). M.Š. (Ğulja), 'Ile vilāyeti vāqıʿaları', Vaqıt, 20 April 1912, p.2. Notes:[1] The author refers to this form of constitution as istiqlāl, a term that connotes sovereign authority, and now means 'indepdendence' in many Turkic languages. By contrasting this istiqlāl with a full-blown jumhūriyyat 'republic', he is referring to the confusing compromise between the Qing court and the revolutionaries, brokered by Yuan Shikai in early 1912, according to which the deposed Emperor retained his title, a lavish income, and other priveleges. News from Ili Province, 10 May 1912 Fig.8 The Ghulja branch of the Russo-Asiatic Bank. (Photograph: G.E. Morrison; courtesy of Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW [a1788107]) On 24 February [8 March] the leader of the Revolutionary Party, Yang Tongling came to Ghulja from Küre. The Kashgaris, Taranchis and Dungans (Chinese Muslims) prepared a welcoming tea and met him outside the city.[1] On 25 February [9 March] Yang Zuanxu paid visits to the Russian Consul, the military officials, postal officials, the chairman of the Russo-Asiatic Bank, and Baha al-Din Effendi Musabayev. They in their turn returned the visit. On 26 February [10 March] at ten in the morning a feast was given at the Musabayevs' in honour of General Yang Zuanxu. To the feast also hosted the acting Russian Consul, the honourable A.A. Diakov, the chief of the Cossack guard. Kopeikin, postal director Mr Zinoviev and his deputy, the chairman of the Russo-Asiatic Bank Suvorov, as well as officials of the new Chinese government, including the Daotai (Vice-Governor) Feng Temin 馮特民, the Xianguan (County Official) Huang Lizhong 黃立中 and others.[2] At the banquet General Yang Zuanxu expressed the hope that the Russian government would welcome China's republic, and that the Chinese Republic wished to remain on friendly terms with Russia. He offered a toast to the health of the Russian imperial family and the progress of that country. Raising his glass in response, Mr Diakov spoke of his wishes for consolidation of the republican government in China, and for the health of the founders of the Republic, Sun Yatsen and his comrades. He also said that the Russian government welcomed the Chinese republic. Mr Kopeikin congratulated General Yang on the victory of his troops in the battle of 18 February [2 March], and expressed the hope that he would be triumphant in future battles. He thereupon made a toast. The banquet broke up at two o'clock. General Yang finished his business on 27 February [11 March] and on 28 February [28 March] he returned to Küre. M. Terjümani. M. Terjümānī, 'Ile vilāyeti ḫeberleri', Vaqıt, 27 April 1912, p.2. Notes:[1] The author refers to this welcoming ritual as a sajang, perhaps a loanword from Mongolian saǰang 'porcelain', i.e., tea cups. [2] One can only make a tentative guess at this man's identity, the Arabic script here is ḪANG LWYD. Huang Lizhong was a businessman from Anhui who was appointed head of the treasury following the rebel victory. Events in Ili Province (19 May, 1912)These days agitation against the republic continues among the Qalmaqs.[1] Word has arrived that six thousand Qalmaqs were coming to lay siege to Ghulja and Küre. On hearing this 'news' the republicans were fearful. They deployed five hundred well-trained soldiers to Ghulja from Küre. Prior to this there had been no Chinese soldiers in Ghulja. Their commanders have them drill daily in the cool of the evening to hone their skills. Those who are versed in military matters say that the Chinese training is based on that of the German military. Since early March those involved in the fighting have been stationary. However, provisions and equipment are still being sent. There is a lot of wrangling over these matters. The Chinese edition of the Ili Provincial News continues to appear.[2] It is read both with great anxiety and with excitement. The Chinese paper here is very thin. Newspapers and books are printed only on one side, the other side is blank. When these newspapers leave the press, they are posted on the walls of busy thoroughfares for passers-by to read.  Fig.9 Ili Provincial News, the Turki edition of the Yili Baihua bao A Turki edition should be appearing soon something the editor,ʿAbd al-Qayyum Effendi (a Russian Tatar) went to Küre to discuss. If the new paper has a style that conforms with the temper of the people (by comparison with the first edition which has closed down due to a lack of readers), it will be a definite advance and greeted enthusiastically by readers. The welter of political change has, to an extent, awakened the people. It has forced them willy-nilly to concentrate on the unfolding trends of the times. Those who previously took fright and recited 'lā hawla'[3] when they heard the name of a newspaper, are now starting to subscribe themselves, or at least borrow them from someone else. They wait impatiently for the post (the Russian post only comes twice a week). Their numbers are still small, and most of them are Russian subjects. Among our Turkic brethren who are subjects of China there are hardly any newspaper readers. Despite this, we comfort ourselves with the happy thought that everything starts from small beginnings, that gradually they will develop and their defenders multiply, and that eventually people will crop up who say that if such-and-such ishan or and-such akhund does it, I will do it too. If in particular one considers that our people are given to mimicry, then perhaps as the days pass the emulation of others in mimicry of this good deed might also multiply. In any case, we hope that this will be the case. Considering all this, the first necessity is that newspapers, as far as possible, be well enough written to attract the interest and demand of the population. Mansur Sheykhof. Manṣūr Šeyḫof, 'Ile vilāyeti vāqıʿaları', Vaqıt, 6 May 1912, p.2. Notes:[1] The Mongols in the district did not greet the nationalist uprising with enthusiasm. One group fled the chaotic situation and migrated to the newly independent Mongolia via Russia. Others crossed the mountains to the south and requested arms and ammunition from the daotai of Aqsu which they hoped to use to defend themselves against the revolutionaries. It is not surprising, then, that rumours of an impending Mongol attack were circulating in Ghulja at the time. [2] This continuation of the Ili Baihuabao was the New Press (Xinbao 新報), the first issue of which appeared on 22 February 1912. [3] The first words of the Arabic phrase lā ḥawla wa lā quwwata ʾillā billāh, which means 'there is no power and no strength other than with Allah', were said to ward off danger. One hadith describes these words as 'one of the treasures of Paradise' (Ṣaḥiḥ al-Bukhārī,, vol.8, book75, no.393). Events in Ili Province, 2 June 1912)Delegates from the xunfu in Ürümchi, a supporter of the Manchu government, and from the revolutionaries in Küre (New Suidun), have left for Chöchäk [Tarbaghatay, Ch: 塔城 Tacheng] for peace talks. The negotiations are to be held in the Russian Consulate. The of revolutionaries' delegates set out on 9 April via Jinghe 精河 under He Daren (a zhifu in the former Manchu government).[1] The group also consists of two civil and two military officials, one telegrapher, thirty to forty Cossack soldiers (as guards) and a merchant. The conditions on which the revolutionaries intend to settle are: 1. There is to be only one da dudu in Xinjiang Province; 2. The da dudu is to be elected by the people or should be appointed by the president in Beijing; 3. The da dudu is to be stationed in Ürümchi, and towns which were previously subordinate to this province should remain so; 4. There should be a single currency in the territory of Xinjiang, and the main treasury should be located in Ürümchi; and, 5. The republican constitution should apply to Xinjiang. If the delegates from Ürümchi are agreeable to these five conditions, then a peace accord can be reached. If not then there will be no settlement. On 14 April [27 April] a telegram from the president in Beijing announced that the daotai of Kashgar had been appointed as da dudu.[2] On 15 April [28 April], a force of two hundred Cossacks with two machine guns arrived, supposedly in order to protect the Consulate and Russian subjects here. M. Terjümani. M. Terjümānī, 'Ile vilāyeti vāqıʿaları', Vaqıt, 20 May 1912, p.3. Notes:[1] He Jiadong 賀家棟, from Changsha in Hunan, appointed zhifu of Ili a few years previously; he returned to Hunan at the end of 1912. [2] This decree was issued on 25 April. At the time, the daotai of Kashgar was Yuan Hongyou 袁鴻祐. Yuan was assassinated by mutinous soldiers in Kashgar on 7 May before he could take up the appointment. Events in Ili Province, 16 June 1912A commission of the revolutionaries led Hu Daren went to Chöchäk to negotiate a peace settlement at the request of the supporters of the Ürümchi government. They arrived in Chöchäk to discover that noone had been sent Ürümchi. They then sent word to the governor of Ürümchi governor asking why this was so and received the reply: 'I've retired and so it's none of my business.'[1] This made the moustaches of the republicans bristle. They decided to force the matter by attacking Ürümchi. To this end provisions and military supplies were hastily despatched. It appears as though success could will be on the side of the republicans, this is particularly so as generally the people of Ürümchi, and in particular its soldiers, are said to be enamoured of the republicans and are hopeful that they forge a way ahead.  Fig.10 Kazakh nomads. (Photograph: G.E. Morrison; courtesy of Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW [a1788089]) The republican flag has now been raised in certain parts of the province of Ürümchi and the Kazakhs here have taken advantage of the weakness of the current regime. They have begun to rob and loot own headmen and chiefs on the grounds that they have grown rich on their livestock and their food. 'You fed us to the Chinese', they declare. 'Now we will reclaim own herds.' The entire livestock and wealth of several headmen in the Turghay[2] territory was plundered by commoners in their jurisdiction. Now they are arming themselves so they can plunder the district officials. They are some five hundred in number and they face an official force of three hundred. If they have the wind behind them and are successful in their a raid, Kazakhs throughout the Ili Valley will be encouraged, their fears will dissolve, and they too will set about raiding their local chiefs. They are just waiting to see the outcome of the clash. There is nothing the local authorities can do to hold them in check. Either that, or they are fearful of stirring them up against themselves. Mansur Sheykhof (Ghulja). Manṣūr Šeyḫof (Ğulja), 'Ile vilāyeti vāqıʿaları', Vaqıt, 3 June 1912, p.3. Notes:[1] The Ili delegation reached Tarbaghatay on 10 May, three days after the assassination of Yuan Hongyou in Kashgar. As a result of Yuan's death the office of provincial governor remained temporarily vacant. Yang Zengxin was not appointed to the position until 19 May. [2] The wording here is ambiguous: Ṭurğay digän il could refer to a Turghay tribe, or to people living in a place called Turghay. Unfortunately, the name Turghay does not appear in any lists of Kazakh sub-groupings in Ili that I have seen, nor is it a familiar toponym in the district (cf. Torghay in western Kazakhstan). News from Ghulja, 21 June 1912Last autumn the Russian Consul Fedorov[1] retired and left Ghulja. [Subsequently,] consular duties were carried out by the secretary of the Consulate, Mr Diakov.[2] Now Mr Diakov has been appointed consul-general in Ürümchi and he will depart shortly. Mr Diakov was attentive to the interests of the traders; he was an advocate of equitable and honest dealing, and he rejoiced in the education and progress of every race. He said that for the traders here to learn Russian was as essential and necessary as food and water, and he intended to open a Russian school. He covered the school's expenses, and requested support from the treasury for teachers' salaries. The people of Ghulja are distressed at Mr Diakov's departure, but we congratulate people in Ürümchi for gaining such a progressive Consul. The new Consul in Ghulja is Mr Brodianskii, a man who previously worked in the Orient (possibly in Korea).[3] As is the custom, the people greeted him with bread and salt. According to those who spend their time at the yamen, Mr Brodianskii is knowledgeable about the East, studies the petitions presented to him in a timely fashion, and treats all the same. As a result, his arrival has been welcomed by the people of Ghulja although he has only been here some five days. The Russians have deployed some two hundred mounted soldiers and two machine guns to protect their subjects here, bringing the number of Russian soldiers in Ghulja to two hundred and fifty. On the third day [following the new Consul's arrival] the general [i.e., Guangfu] arrived with a musical escort. The musicians will be here throughout as the general's stay. The renowned Yang Tongling has [also] returned to Ghulja, most probably to pay a visit to the new Consul. The Russian soldiers, either in honour of Yang Tongling, or for some other reason, put on a zhigitovka (a military show). On that occasion the sky was clear and it was cooler than normal. It was though the heavens were saying: 'let the people of Ghulja, who have not had any entertainment for some years, enjoy themselves. Let them relax and watch'. A banquet was held for Yang Tongling by the consul from two until around four o'clock that afternoon in the garden of the Consulate. Afterwards everyone, be they young or old, rich or poor, on horseback or travelling by foot, hurried to the north of Ghulja to see the military display. We also went to see it, travelling in the cart. We travelled five or six versts.[4] We came across a basin of about one verst square, at its foot water did not flow (it was flat), and it was covered with yellow soil. After a certain distance its sides gradually got higher. It was a natural auditorium, just like one of those huge theatres in great cities that cost thousands of roubles to build, where all can see, and none are deprived of the spectacle. People were squatting around the sides of the valley, on one side a tent had been erected for dignitaries, with samovars boiling away. On the other side were some old black Kazakh yurts, and in front of them in people were gossiping in various tongues about all kinds of things. In the middle of the valley the musicians made the air reverberate with their playing. At the appointed hour the dignitaries of both countries had arriving (Yang Tongling was also present), and the zhigitovka started… All in all, the zhigitovka turned out well, the soldiers having displayed great skill and expertise. At one point they ran to the Kazakh yurts and made off with a Kazakh girl; thereupon, and this was particularly amusing, a Kazakh woman jumped on a cow and chased after the girl, screaming all the way! This delighted the crowd and made everyone laugh until their bellies hurt. It turned out that they weren't Kazakhs at all, but players dressed up in Kazakh costume. The festivities continued for three hours. Mansur Sheykhof (Ghulja). Manṣūr Šeyḫof (Ğulja), 'Ğulja ḫeberleri', Vaqıt, 8 June 1912, p.2. Notes:[1] Sergei Aleksandrovich Fedorov was Consul in Ghulja from 1904 to 1911 and the author of a description of Ili, Opyt voenno-statisticheskago opisaniia Iliiskogo kraia, Tashkent: Tipografiia Shtaba Turkestanskago Voennago Okruga, 1903. [2] Aleksei Alekseevich Diakov was the Consular Secretary in Ghulja from 1906 to 1912 and Consul in Ürümchi from 1912 to 1917. [3] Lev Grigorevich Brodianskii was Vice-consul in Seoul in 1911, in Incheon 1911-12 and consul in Ghulja during the years 1912-16. [4] Here the author uses the Turkic unit of measure chaqırım, literally 'the distance at which a shout can be heard'. In contemporary Tatar usage it corresponds to the Russian verst (=approx. 1.0668km), as it probably does here. Events in Ili Province, 25 June 1912These days the Russian and Chinese officials and local worthies are occupied visiting one another, hosting banquets and dealing with guests. Previously it was noted that Yang Tongling had come from Küre to Ghulja for a second time. On the third day Ili's da dudu (President of the Republic) also came. He is busy with inspections. Yang Tongling travelled regaled in military uniform and seated in entirely European fashion in military dress in a cart with two large flags raised, one white the other red. However, the da dudu rides a horse, is dressed in the Chinese fashion and has three red flags. Both are accompanied by a military escort and their movements are accompanied by appropriate pomp and ceremony. For the first few days of the visit Yang Tongling was followed by locals who gawked at his clothes, his cart and all the attendant pageantry. Eventually, curiosity satisfied, the spectators melted away. , A Chinese musical troupe that played at special feasts also appeared, presumably in honour of the da dudu. The musicians were all young children. The Chinese music, was lively and melodious to the ear—evidence that among these Chinese there is a also considerable aptitude for music. People say that they were playing in tune, too. Among the Chinese there were no new sumptuary regulations; they were free to wear what they pleased. If someone has the money, be they soldier or citizen, they buy whatever catches their eye and dress up in it. Bakers sport the same chekmen cloaks with red lining that soldiers and generals wear, and go around attaching colonel's epaulettes to their jackets. They can't get enough of such finery. According to the merchants, young Chinese very much enjoy wearing käläpüsh (Kazan skullcaps), and a lot of them are being sold. Even out on the streets one meets a lot of Chinese who have donned the skullcap. Local skullcap dealers say that they will enjoy a large turnover in their wares, and our progressives are happy that 'Muslims' are on the increase. As far as I know, the true reason is probably as simple as this: Chinese liberated from the strict [old] regime are like birds that have been set free from captivity, they are bewildered and don't not know quite what to do. They see others wearing skullcaps and, thinking that these people are wearing them for some reason, the Chinese decide to wear them too. Events in Ili Province, 30 June 1912The Republic is being consolidated, and it is continuing to put down its roots and strengthen its branches. The leader of the troops fighting with the Ürümchi forces, Ma Tongling, has returned to Küre; he also visited Ghulja. The other troops have also started to return. A few soldiers were left behind for security. In other words peace has been established on the fronts where previously the greatest anxiety existed. There is now no present danger. The [Qalmaq] Mongols who came, or were intending to come to lay siege to Küre and Ghulja have disappeared of their own accord. The Chinese soldiers who had come to defend Ghulja have likewise returned safely to Küre without bloodshed. Currently there are few if any Chinese soldiers left in Ghulja. Of the Kazakhs who robbed their own officials, those who had incited the violence were taken into custody by the local authorities and tried. The livestock and goods they stole were restored to their owners. These Kazakh who had been smitten with a desire get rich and made ready to rob their own chiefsbecame an object lesson to other Kazakhs. Their hearts wavered, their spirits sank, and they turned away from thoughts of brigandage. In other words, among the Kazakhs too the danger has passed. The Manchus in Küre who were stalwarts of the old regime and afraid that after the first Jiangjun was killed the new government would suppress them, had moved to Ghulja with their families and thrown themselves on the mercy of the Russian Consul. They abandoned their homes in Küre, but there were no empty houses in Ghulja; they had all filled up with Chinese. Rent in Ghulja thus rose as much as tenfold. It had become very difficult for homeless and indigent people to remain. Recently the da dudu announced that: 'Peace has been established in Ili and there is no cause for fear. Everyone should be master of his own home and carry on his trade and occupation as before. Empty homes will be seized by the treasury after a certain time. Do not be negligent!' At the moment, although rents have fallen slightly, they are still higher than usual. Related material from China Heritage Quarterly:

|