|

|||||||||||

|

NEW SCHOLARSHIPJust Images: Ethics and Documentary Film in ChinaYing Qian 钱颖 Harvard University*

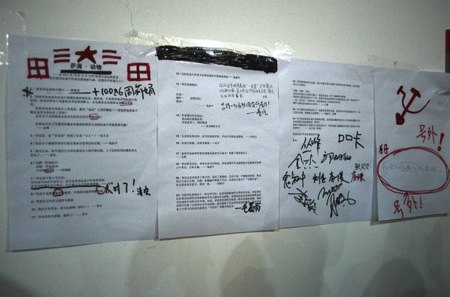

In previous issues of China Heritage Quarterly we have published material related to the documentary film The Gate of Heavenly Peace and attempts by one of the protagonists of China's 1989 protest movement to use the U.S. court system to silence independent filmmakers (see here and here). The film (as well as its makers, including the editor of the present publication) has also been the subject of theory-laden dissection as well as risible pseudo-academic throw-back Maoist analysis. In 2011, ethics in documentary film became a prominent area of contention within the world of Chinese independent cinema. The following article by the Harvard-based scholar Ying Qian offers an overview of the debate.—The Editor A Forum and a ManifestoOver the past two decades, one of the most important developments in Chinese visual culture has been the flourishing of independent documentary film. Celebrated at international film festivals, and gaining a limited but growing domestic exposure in galleries, cafés, as well as at the small number of independent Chinese film festivals, this vibrant cinematic form has been admired for the resistance of its makers to state censorship, and a commitment to registering everyday experiences in a period of dramatic social transformation.  Fig.1 The documentary film, Wheat Harvest The close bond between documentary cinema and real life, however, not to mention the complex relationship between filmmakers and the party-state make the genre particularly open to ethical concerns. As Chinese independent documentary continues to blossom, and its circulation widens, 'documentary ethics' (紀錄片的倫理) has become an increasingly pressing concern. For example, Xu Tong's 徐童 film Wheat Harvest (麥收), a film about the lives of female sex-workers in Beijing, sparked considerable controversy and led to audience protests when it premièred at the Yunfest Documentary Film Festival in Kunming, Yunnan 云之南纪录影像展 (see: http://www.yunfest.org/), in March 2009. As prostitution is a statutory crime according to Chinese law, the exposure of these women as sex-workers raised questions about whether their appearing in a documentary could be injurious to them, or possibly even lead to arrest. Labor and feminist NGOs criticized the filmmaker for failing to tell his subjects how their images would be used: in some instances the interview-participants in the film were not even aware that they were being recorded. Contributing to the gravity of the issue was the fact that, in this instance, the sex-workers had no redress in regard to the filmmaker, as their own shaky legal situation made it impossible for them to seek legal protection or take action against him. Some film critics and scholars, however, argued that the ethical issues of the film were not as clear-cut as the NGO critics claimed. The film scholar Guo Lixin 郭力昕, of the National Chengchi University 国立政治大学 in Taiwan, argued that the filmmaker had been sensitive and respectful towards his subjects, and that the resulting work could help bring about a change in social perceptions of prostitution.[1] The debates surrounding Xu Tong's Wheat Harvest energized the debate surrounding documentary ethics. In recent years, lively (and sometimes vociferous) discussions have revolved around questions regarding the legitimate use of hidden cameras, the aestheticization of suffering, and the parading of a 'backward' China to a supercilious or complacent Western gaze. The discussions have broken out at film festivals and during post-screening Q&A sessions. In fact, in China today the ethics of film making has moved to centre stage in documentary film discourse. In 2011, two dedicated symposia were organized around the topic. The most recent of these was held in October 2011 at the Nanjing Independent Film Festival. Long-time observers and scholars of independent documentary, such as Lü Xinyu 吕新雨, Wang Xiaolu 王小鲁, Angela Zito (New York University), and Guo Lixin (National Chengchi University, Taiwan, as above), and filmmakers such as Ji Dan 季丹, Xu Tong and Cong Feng 丛峰 participated in the discussion held under the title 'Paths of Chinese Documentary: Politics, Ethics and Aesthetics' (中国纪录片之路—政治、伦理与美学).[2] This essay offers an interpretative summary of the dialogues and debates at the Nanjing Forum, which to the author's knowledge is the latest and one of the most focused discussions on the issue to have been held in China. My analysis also includes filmmakers' responses to the Nanjing Forum in the form of what has been called the 'Nanjing Manifesto' (南京宣言). Infuriated by what they perceived to be a dominance of intellectuals and theoretical language at the forum, a group of filmmakers issued the Manifesto the day after the Nanjing Forum concluded. Entitled 'Shamanism-Animal: Responses to the Nanjing Forum' (萨满 ∙ 动物—对2011年10月31日CIFF纪录片论坛的回应), the Manifesto was a collage of individual responses. It was posted on the wall of the site of the Nanjing Film Festival, very much in the tradition of posting 'big character posters' (大字报 [large hand-written posters were used as both a popular and official vehicle to express disagreement and derision during the Maoist era (1950s-70s). Their use was banned in the early 1980s—Ed.]). The Manifesto expressed the filmmakers' views about documentary ethics in their own style; it was also pointedly critical of academics and film critics for their perceived rigid and homogenizing views, and what was taken to be a condescending attempt to police the field.[3] Can the Subaltern Speak through the Lens of a Camera?One of the most important issues germane to discussions of documentary ethics involves the relationship between the filmmaker and the filmed subject. The majority of Chinese independent documentary films depict the lives of people at the 'bottom rung' of the society (shehui diceng 社会底层). This has made the ethical issues in contemporary Chinese documentary film more acute. As they often work and live outdoors and literally have little to shield themselves from being captured by a filmmaker's viewfinder. 'Chinese documentaries are very colorful and exciting, but the realization of these films… has often depended upon the visibility and filmability [可看性和可拍性] of raw materials [素材] in China, in particular, the bottom layer of the society'. So wrote the film critic Wang Xiaolu, one of the organizers of the Nanjing Forum in an article published in Film Art in 2011.[4]  Fig.2 Protest at a screening of the film Wheat Harvest at the Hong Kong Chinese Documentary Film Festival The main focus of the Nanjing Forum was the question of how the subaltern (that is those of lower socio-economic status) can be responsibly represented in film. In his remarks at the forum Wang Xiaolu re-iterated the idea alluded to in his earlier article, that is that independent documentary should affirm a 'contractual spirit' (契约精神) wherein both filmmaker and subject respect their obligations to one other. Wang drew on a perception of a liberal intellectual tradition wherein equal rights, consent and social contracts are the corner stones of any kind of political or social legitimacy. As one of the organizers of the Nanjing Film Festival (中国独立影像年度展; http://www.chinaiff.org/), Wang had already helped establish the festival's 'Real Character Award' (真实人物奖). Awarded for the first time in 2011, this prize is meant to initiate a new tradition by inviting to film festivals not only filmmakers but their collaborators/subjects as well. Wang observed that while independent documentary films have enjoyed a measure of popularity both domestically and internationally, people who have shared their lives with filmmakers have previously had no opportunity to travel with their own images. Instead, they have been held 'prisoner in the film', repeatedly put on display, and subject solely to the filmmakers' interpretative maneuvers. Inviting filmed subjects to attend screenings and festivals avails the subjects an opportunity to interact with audiences, as well as to challenge the filmmaker's monopoly on interpreting their lives. In 2011, Tang Xiaoyan 唐小雁, the central figure in Xu Tong's new film Old Mr Tang (Lao Tangtou 老唐头), was the winner of the prize, and he appeared at the festival and forum with the filmmaker Xu. Wang Xiaolu's 'contractual spirit' and the 'Real Character Award' are innovations aimed at addressing some of the ethical issues generated by documentary film practice, but both initiatives were criticized at the Nanjing Forum by Lü Xinyu, a Shanghai-based film scholar who has been studying independent documentary cinema since the early 1990s, and whose 2003 book Recording China: the New Documentary Movement 纪录中国—当代中国的新纪录运动 was seminal.[5] For Lü, the bifurcation of the Chinese society into the lower castes and elites made it impossible for meaningful 'contracts' to be co-signed by individuals across the social divide. She argued that such 'contracts' serve merely to protect filmmakers, while their subjects lacked the wherewithal to enforce the contract if it is breached. Even though Tang Xiaoyan had participated willingly in the film festival to support a filmmaker, Lü warned that her presence should not be considered to be the embodiment of 'subaltern consent'. Coming from a leftist tradition, Lü borrowed from the maven of subaltern studies, Gayatri Spivak, to argue that there is a fundamental, unbridgeable disconnect between the subaltern and the rest of society. She declared that people from the bottom layer of society have no voice, and that they cannot meaningfully consent to the agendas of those who are more powerful.[6] The 'subalternization' of a large section of the Chinese population has posed a new ethical challenge to documentary film practice, argued Lü. She recalled that in the early 1990s, when independent productions of documentary films began to emerge, the word diceng, or the bottom layer or echelon, was not an existing term in China's socio-political vocabulary. At first, filmmakers were not so different from the people they filmed, and documentary films were perceived as telling the stories of common people (laobaixing 老百姓). The inequalities that developed in the 1990s and deepened over the past decade have given rise to frequent appearances of the term diceng in Chinese discourse and, Lü argued, that it is this 'brokenness' of society that has exacerbated the ethical dilemmas now present in documentary film practice. In a characteristically scholarly move, Lü went on to attempt to list three modes according to which the subaltern is represented in independent documentary film: 1. The 'populist mode': 'populist' filmmakers express their admiration for the dignity and nobility of people at the bottom of the society, and expose the injustices and grievances of these people. By doing so, the filmmakers offer a critique of the existing social order and through their practice agitate for social change;, 2. The second could be dubbed the 'realist model': filmmakers do not entertain a romantic view of the bottom layer, but instead attempt to understand it and operate according to the internal logic and codes of behavior of a sub-society (that is 'untamed realm' jianghu 江湖) beyond the bounds of legal and social control; and, 3. The third is what I would call the 'carnival model': through depictions of the lower class filmmakers such as Xu Tong attempt to connect audiences with sexuality and bodily experiences, which they perceive to be less repressed among society's 'others' than in the mainstream. These models of representation are, essentially, three distinct authorial positions that reflect different aesthetics and epistemologies, as well as different ways of interacting with filmed subjects. In her talk Lü only elaborated on the 'populist model', which she praises as being the quintessential position taken by 'Chinese intellectuals'. She traced its genealogy back to populist Russian thinkers and writers such as Ivan Turgenev and Maxim Gorki.  Fig.3 The 'Shamanism-Animal' manifesto Lü's evocation of the Russian populist tradition, and its association with the Soviet revolution, immediately elicited suspicion and criticism from other participants in the forum. This, plus Lu Xinyu's unexplained dismissal of the other two models, as well as her unabashed intellectual hauteur in categorizing and evaluating the work of filmmakers from an assured position of theoretical certainty, lead to heated responses. Her assumption that the society is irreconcilably split into stable categories of the powerful and the powerless, and that the filmmaker invariably sides and resides with the powerful, was regarded as being too simplistic and one-dimensional. This, at least, was the counter argument posed by Zhang Xianmin 张献民, a professor at the Beijing Film Academy. Others reasoned that, while a filmmaker may have acquired the social resources to become a member of the cultural elite, many have themselves grown up in under-privileged families, and continue to have profound personal, and empathetic, connections with the lower orders. Yet others argued that class does not determine a filmmaker's capacity to understand and express the experiences of the socially downtrodden: also important is the filmmaker's self-awareness, reflexivity, and the effectiveness with which he or she works with film aesthetics. Speaking against the reliance on sensationalism and shock value to attract attention, Guo Xizhi 郭熙志, a film scholar and filmmaker based in Shenzhen, argued that ethical issues in documentary might not only reflect social and class divisions, but also a poverty of aesthetic imagination and artistic vision. In other words, film as an artistic medium can overcome the class divide; but its potential can only be explored when a filmmaker is aware of the ethical complexities of representation and thereby transform these constraints into an impetus for aesthetic innovation. Finally, documentary ethics is not limited to the relations between the filmmaker and the subject. Guo Lixin, a film scholar from National Chengchi University in Taiwan mentioned earlier, argued that the highest ethics of a documentary is the political insight it offers an audience, something that allows the audience to understand the hidden structures of the society, the inter-connectedness of social experiences and the potential for (positive) social change. He criticized the excessively melodramatic TV documentary practice in Taiwan that, in his opinion, reduces complex social and political experiences into family dramas or psychological trials of the individual, Guo Lixin has a similar understanding of cinema to that held by practitioners of the 'Third Cinema', especially their preference for a 'lucid cinema for lucid people, who think and feel and exist in a world which they can change.'[7] The Nanjing Forum continued for a heated five hours. The discussion focused predominantly on the position of filmmakers in relation to the subaltern. Other important topics, such as the relationship of filmmakers to the party-state and to the international film festival circuit, as well as the ethics of watching and exhibiting documentary films were left untouched. While many filmmakers were present, they only infrequently participated in the discussion. Rather the event was dominated by the discourse of academia and theory. If the forum could itself be interpreted as a hierarchy of voices, then the filmmakers had become the 'subaltern' of the field, people who had lost their voices. Cinema as ShamanismThe day after the Nanjing Forum, a number of filmmakers issued a manifesto entitled 'Shamanism-Animal' (萨满-动物). Composed of a collage of short statements by sixteen filmmakers, and with signatures under each statement, the Manifesto was not meant to represent a unified position, but rather it was a bricolage of responses from individual creators.[8] Regardless, the Manifesto still reflected a number of shared ideas. In effect, the filmmakers collectively declared that film has its own language and logic, and that it is separate from the scholarly enterprise of theorization and classification. They expressed a general suspicion of theory: 'That thing called theory, when spoken of in excess becomes dogma; beyond a certain threshold, it becomes totalitarianism', writes Hu Xinyu 胡新宇. For the filmmakers, documentary is the opposite of theorization: it doesn't posit a priori knowledge. 'The motivation to document comes from being ashamed of one's own ignorance', wrote Hu. Theory, on the other hand, is like 'absent observation', argued Mao Chenyu 毛晨雨. The signatories to the Manifesto would appear to share a common belief that documentary cinema is an art form possessed of an innate logic that can only be appreciated outside the realm of rational reasoning . As Qiu Jiongjiong 邱炯炯 wrote: 'Documentary is like making love'. Filmmaking is also compared to shamanism. The title 'Shamanism-Animal' is attributed to the filmmaker Ji Dan 季丹, as she has reportedly compared the filmmaker to a shaman, both being conduits through which others find voice.[9] Ji Dan has been active since the early 1990s, and she is one of China's best-known new ethnographic filmmakers. Her earlier films were made in Tibet where she lived, learned the local Tibetan dialect, and spent long periods of time with local families. She was among the filmmakers whom Lu Xinyu classified as 'populist'. Present at the forum, Ji Dan was caught by surprise by Lu's classification. While declining to comment at the forum, Ji Dan wrote in the Manifesto: 'We are not making revolution, but just giving you a wake-up call (当头棒喝). Arrogance would be the reason for revolution, that'd be the end of it all' (我们不是革命,是当头棒喝! 革命是因为骄傲,就得了! ). The term Ji uses for 'wake-up call', dang tou bang he is a term associated with the tradition of Buddhist meditation: the meditating monk would suddenly be struck by his master, something supposedly meant to bring about instant realization or awakening. Moving away from the language of scholarship, and the populist tradition associated with revolution, Ji Dan prefers to use the language of religion and mysticism to explain her idea of what a filmmaker is, and what filmmaking as a practice can bring into existence.  Fig.4 Filmmaker Xu Tong The idea of filmmaking as a kind of shamanism is an intriguing one. A number of international precedents come to mind. Jean Rouch, the French ethnographic filmmaker whose idea of cinema verité and participatory cinema has had a profound influence over the years, coined the term 'cine-trance' to describe the revelatory, altered state of consciousness induced by the camera in filmmaker, his/her subjects and the audience alike. Joseph Beuys is also famous for his idea of the role of the artist's shamanic role in society. Both Rouch and Beuys are well-known in China. Indeed, in April 2011, some six months before the Nanjing Forum, the journal Contemporary Art and Investment published an issue devoted to Beuys entitled 'Beuys: a Smiling Shaman'.[10] Apart from emphasizing the unique ontology of film as artistic practice and as a bodily, sensory and even transcendental medium for communication, in the Manifesto the filmmakers also protested against the condescending attitude of academics and film critics and their assumption of the role of rule-makers and enforcers in what is an emerging artistic field. 'Critics cannot monopolize history', they declared. 'Critics have to learn from filmmakers, instead of posing as their mentors', wrote Cong Feng. He argued that critics should best reflect on their own ethical conduct, and stop assuming leadership positions in the field. Obviously, filmmakers do not like to be 'disciplined'. A blogpost entitled 'Shaman, Animal, Circumcision' (Saman—dongwu—ge baopi 萨满-动物-割包皮)', by Xue Jianqiang 薛鉴羌, a younger filmmaker said that even though critical writing on cinema is speculative, he would support it if opens up new possibilities for this creative form, but not when it tries to determine a 'history' of the field as a whole.[11] ConclusionContracts, revolutions, Russian populists, and shamanism: if one still had doubts about the vitality and restlessness of the Chinese documentary scene, the Nanjing Forum and the competing Manifesto would dispel them. After two decades in the making, the field of independent Chinese documentary filmmaking is coming of age, and the issue of documentary ethics has emerged as an arena in which a range of ideas interact and contend. What is at stake for these struggles is the shape and style of the field in the future: the structure of governance and the distribution of power, normative discourses and counter-discourses, and the extent of artistic innovation, critical engagement, and communal identity. Beyond the field of independent documentary, this discourse is also relevant to the future contours of other realms of cultural criticism and reception in China.

Notes:* My thanks to the editor of China Heritage Quarterly, Geremie R. Barmé, for inviting me to write this essay and for his extensive editorial suggestions and revisions. [1] Guo Lixin 郭力昕, 'The Rights of Sex Workers, Sexual Morality and Self-righteousness (妓權、性道德、與自我正義―再談《麥收》與紀錄片的倫理) Kulao wang (苦劳网), 31 August 2009. Online at: http://www.coolloud.org.tw/node/45653. Accessed on 21 February 2012. [2] The transcript of the proceedings at the Nanjing Forum can be found at the website of the China Independent Film Festival of Nanjing. Online at: http://www.chinaiff.org/html/CN/xinwen/xinwenliebiao/2011/1231/1775.html; and, http://site.douban.com/widget/notes/5532008/note/193132468/. Accessed on 21 February 2012. [3] For transcripts and photos of the posters, see: http://site.douban.com/widget/notes/5494326/note/181581347/. Accessed on February 22, 2012. [4] Wang Xiaolu 王小鲁, 'The Contractual Spirit of Chinese Independent Documentary' (中国独立纪录片的契约精神), Film Art (电影艺术), 2011 (5): 93-98. [5] Lü Xinyu 吕新雨, Recording China: The New Documentary Movement (记录中国:当代中国新纪录运动), Beijing: Sanlian Shudian, 2003. [6] Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, 'Can the Subaltern Speak?', in Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg, eds, Urbana, Il: University of Illinois Press, 1988, pp.271-313. [7] See Mike Wayne, Political Film: the Dialectics of Third Cinema, London: Pluto Press, 2001, p.42, for a discussion of J. G. Espinosa's notion of a lucid cinema. [8] They are: Xue Jianqiang 薛鉴羌, Cong Feng 丛峰, Zhang Chacha 张叉叉, Gui Shuzhong 鬼叔中, Jin Jie 金杰, Qiu Jiongjiong 邱炯炯, Song Chuan 宋川, Ji Dan 季丹, Bai Budan 白补旦, Feng Yu 冯宇, Hu Xinyu 胡新宇, Mao Chenyu 毛晨雨, Wang Shu 王姝, Beifang Lao 北方佬, Cao Kai 曹恺 and Yang Cheng 杨城. [9] Personal communication with J.P. Sniadecki, 20 February 2012. [10] 'Beuys: a Smiling Shaman' (博伊斯:微笑的萨满) Contemporary Art and Investment (当代艺术与投资) May 2011. [11] Xue Jianqiang 薛鉴羌, 'Shaman, Animal, Circumcision' (萨满-动物-割包皮), a blogpost at: http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_4385d5050100zlw3.html. Accessed on 22 February 2012. |