|

|||||||||||

|

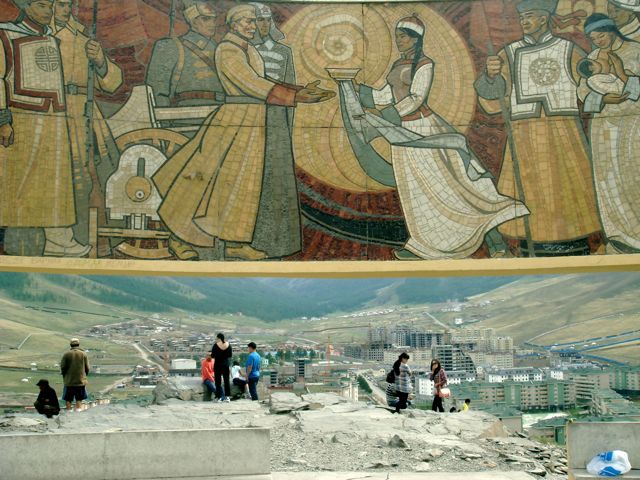

NEW SCHOLARSHIPThe Past and Present of Inner Asian StudiesAn Australian Centre on China in the World Research Theme Workshop 23-24 March 2012David BrophyAustralian Centre on China in the World Much intellectual energy has been devoted to defining the landlocked territories that surround the agricultural heartland of China. Alexander von Humboldt's already confusing tripartite division of Inner Asia, Middle Asia and Central Asia is only the beginning. To these we might add the French 'High Asia' (Haut Asie), Russian 'China Beyond the Wall' (застенный Китай), 'Eurasia' in its various guises, or more recent contributions such as Zomia, whose boundaries could arguably be extended to the mountains and steppes of China's northwest.  Fig.1 The past and present of Inner Asia: The Zaisan memorial to Soviet-Mongol friendship, framing a view of Ulaanbaatar's newest suburbs (Photograph: Ying Qian)

Acknowledging this confusion of categories, at least from the perspective of Chinese Studies in the English-speaking world, there is an emerging notion of 'Inner Asia' as this Chinese periphery. Yet such a category encounters resistance in China, and enjoys little traction among ethnic minority scholars as well for whom the ethno-national unit usually defines the boundaries of scholarly enterprise. Exploring the various traditions at play in our vision of this part of the world, and reflecting on what is at stake in the competition between them, was the goal of a workshop held at The Australian National University (ANU), 23-24 March 2012 under the title 'The Past and Present of Inner Asian Studies: towards defining places, nomenclature and approaches'. Co-sponsored by the Japan Society for Inner Asian Studies and ANU's Mongolian Studies Centre, the workshop marked a step towards broadening the scope of the 'China Time' research theme of the Australian Centre on China in the World. The first panel of the workshop considered the Qing legacy, opening with Mark Elliott's presentation on the New Qing History and its reception among scholars in China. Joe Lawson's 'Passing as Inner Asian: Xikang and its Peoples in the Early Twentieth Century' took up categories of political geography in the Ming-Qing-Republic transitions, considering the role of the 'pass' as determinant of the dichotomy of Inner Asia and China Proper. Then David Templeman spoke on 'Tibetans as "Inner Asians"', asking whether or not there is a Manchu-centric bias in New Qing History, one that obscures the view of Tibetans as independent actors internationally, actors as capable of manipulating as being manipulated. The second panel was united by an interest in Japanese scholarly traditions. Lewis Mayo opened up the geographic frame of reference of the workshop by looking at Dunhuang Studies in its relationship to Toyogaku 東洋学 and Pacific Studies. Set against the rise of maritime powers such as Japan, he argued, 'scholarly work on the Dunhuang texts and artefacts appears as a form of inquiry framed by the shift from land-based to pelagic empire.' Following this, Onuma Takahiro discussed more recent trends in Silk Road/Inner Asian Studies in Japan, charting post-WWII controversies challenging the pre-eminence of the 'Silk Road' in popular and scholarly views of the region. In her talk Li Naranggoa spoke about 'Japanese Images of the Mongols', drawing on a wide range of literary and artistic depictions of Japan and Mongolia, covering a broad range of issues, from hypotheses related to Genghis Khan's Japanese heritage (the legend of Yoshitsune), to the exploitation of Mongolian history for anti-Western ends (the representation, for example, of Marco Polo as the instigator of the Mongolian invasion of Japan). In the third session, which focussed on Islamic minorities, Christopher Rea discussed the domestication of the Xinjiang folk trickster Nasriddin Effendi / Afanti 阿凡提 in Sinophone Chinese culture since the 1950s, as an 'an endearingly unthreatening portrait of Uyghurhood.' Anthony Garnaut examined the notion of 'Inner Asian Islam' as a problematic category, looking at Han Kitab (Islamic texts in Chinese) works which profess loyalty to the Qing and compatibility of Sinophone Islam, implicitly or explicitly rejecting association with Inner Asian centres of power such as the Junghar Mongol court, or the Sufi strongholds of the Tarim Basin. In the final paper of the day, David Brophy considered Turkology as a discipline and its role in mapping the ethnography of China's northwest, particular as practiced by the Russian/Soviet school. The second day of the workshop returned to a discussion of Chinese discourses. Justin Tighe presented his research on the pioneering female pilot Lin Pengxia 林鵬俠, active in the transition period of the 1930s, when China's north-west went from being regarded as a site of national crisis to one of national revival. Finally, Tom Cliff drew on his fieldwork experiences among employees of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps 新疆建设兵团 to probe the idea of frontier 'construction', comparing the self-narration of the early generation of PRC migrants to Xinjiang (self-styled 'constructors' 建设者) with that of more recent arrivals. The concluding discussion dwelt on ambiguities in the use of the concept of 'frontier'. Inner Asia seems inherently to refer to China: the Qing did indeed transform these regions into an imperial periphery. As such, Inner Asian perspectives might be seen as complementing and enriching a full view of Chinese history. Yet frequently Inner Asia is treated not in this way, but at one of two extremes: either as an interesting sidelight that has little to contribute to mainstream Chinese history ('Frontier Studies' as a distinct field), or as something too close, a presence that threatens to destabilise the very notion of Chinese history, for example, the view that the Qing should be regarded as an 'Inner Asian' polity that occupied China from without. Meanwhile, the growth of interest in Inner Asian perspectives can itself call into question the 'frontier' as a guiding concept. After all, one person's distant frontier is another person's homeland. This will be an ongoing conversation, one that must involve scholars from a variety of backgrounds. It is one which will necessarily be influenced by the direction of China's political and social development. We might ask, for example, how the 'frontier' and 'Frontier Studies' in China will look, for example, if and when the Chinese Communist Party achieves its goal of equalising economic indicators and living standards across the nation? |