|

|||||||||||

|

NEW SCHOLARSHIPA Chinese Reformer in ExileAssociation of Asian Studies Panel Report, 16 March 2012Jane Leung Larson

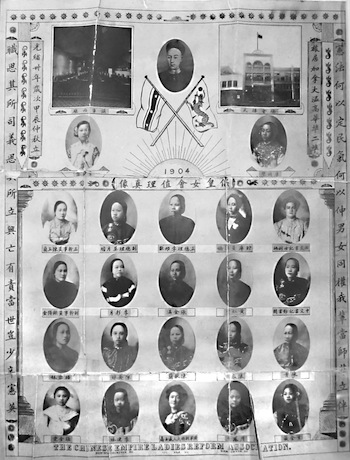

The following is an account of a panel at the Asian Studies Association annual conference, held in March 2012 in Toronto, Canada. The full title of the panel, convened by Jane Larson, was 'A Chinese Reformer in Exile: Kang Youwei and the Baohuanghui 保皇會 as Transnational Chinese History'. The participants were: Jane Leung Larson (chair), Belinda Huang, Evelyn Hu-DeHart, Zhongping Chen, Robert Worden and John Fitzgerald. This account, which offers a summary of each of the presentations at the panel, is reproduced with the kind permission of Jane Leung Larson from the Baohuanghui site with minor emendation. For an account of the work of Jane Leung Larson and the Baohuanghui site, see here.—The Editor PerspectivesJohn FitzgeraldHow does one write a transnational Chinese history of Kang Youwei's years in exile and the reform movement he led while abroad? After reading our papers about Kang Youwei in the US, Canada and Mexico, the Australian Sinologist John Fitzgerald pictured 'historiographical continents colliding', grinding together Chinese history, North American history, with Chinese diasporic studies in the middle. He proposed a world historical perspective that took into account the movements of people, the hardening of state boundaries (as expressed, for example, in the Chinese Exclusion Policy in the US), and increasing nationalism on all sides, alongside shared visions on both sides of the Pacific of a future one-world utopia—Edward Bellamy's Looking Backward, which influenced Kang Youwei's Datong Shu. Fitzgerald speculated that Kang was perhaps the best-traveled writer of his time with the highest access to power. In North America alone, he visited fifty cities and towns in the US and ten in Canada, and spent many months living and traveling in Mexico. Traveling around the world, Kang had 'ready entrée into elite society, not just Chinese communities. Mayors, Governors, Governors General, the US President, the Secretary of State, even the King of Sweden drops by for a cup of tea!' Fitzgerald has written about Kang's 'awakening' as a Confucian utopian and said he'd assumed that the 'panoptic vision of a rational Confucian bureaucrat' was behind Kang's program for a one world government. But the panel papers revealed Kang to be 'a One World Frequent Flyer … an early kind of World Bank or Asian Development Bank official, who travels very [long] distances, very fast, business class, meeting with leaders and telling the world what its problems are and how to solve them.' Fitzgerald marveled at Kang's hyper-rational approach to how governments should work together and his attempts to get Great Britain and the United States to use military force to restore the Emperor. Kang thought that: 'the world should be organized into equal nations, it's the common duty of global citizens to help each nation realize its destiny, so let's make China a better place … we're all in this together!' This precocious form of 'high order nationalism' was ahead of its time and doomed to fail. When no governments came to his aid, Kang pivoted to overseas Chinese and galvanized their energies by providing these already successful business elites with unparalleled investment and networking opportunities through the Baohuanghui and by championing their cause against discriminatory North American policies toward the Chinese. Kang never visited Australia, said Fitzgerald, but Liang Qichao's reception in Australia was quite similar to Kang's in North America and resulted in the founding of eleven Baohuanghui chapters and Liang's attendance at the founding dinner of the Australian nation in 1901. Kang Youwei's Travels in Canada, the United States, and Mexico, 1899-1909: An Outline of His ItineraryRobert L. WordenThe panel was inspired by a dissertation written forty years ago—'A Chinese Reformer in Exile: The North American Phase of the Travels of K'ang Yu-wei'—by Robert L. Worden. We hope to revive and update this valuable dissertation and see its publication as a book. Worden's presentation, in Fitzgerald's words, was 'an elegant overview of the people, places and issues' encountered by Kang in North America, where he spent twenty-nine intermittent months between April 1899 and June 1909. Worden contends that Kang's North American experience was transformative for him and for his historical role as a 20th century political figure. Ultimately, says Worden, Kang's twentieth-century achievements contributed more to China's political development than did the nineteenth-century Hundred Days of Reform.  Fig.1 The Chinese Ladies Empire Reform Association of Vancouver, British Columbia (Source: Vancouver City Archives) Kang's exile experiences had broadened his world outlook and provided ample opportunities to record his thoughts in writing. He witnessed the phenomenal growth of the reformist movement and then saw its collapse. The years during which he traveled in North America and elsewhere, however, were evolutionary for Kang and helped establish him as a significant twentieth-century figure. He exchanged ideas with numerous influential foreign political, economic, and religious leaders whom he met during his travels, and sought their assistance in establishing a constitutional monarchy in China. He met with and helped organize the elite and rank-and file of overseas Chinese communities and emerged as their champion in trying to reform their native land while endeavoring to help them overcome the prejudices of their adopted lands. His opposition both to Qing absolutism and the US Chinese exclusion laws was popular among Chinese in North America and even among many non-Chinese. The competition between pro-reform and pro-revolution factions strengthened both sides and, for a time, overseas financial and moral support leaned more to Kang's less radical and less risky cause than Sun Yat-sen's call for revolution. But as the Qing proved impermeable to progress and constitutional government, opposition political forces became more radicalized and the only meaningful alternative to the status quo, despite too-little-too-late Qing efforts at reform, was revolution. The Baohuanghui and the later Imperial Constitutional Association 帝國憲政會 were an important transitional force in the years between when reform ideas were popular and revolution became inevitable. Thus, one can argue that Kang's and the Baohuanghui's failure helped pave the way to revolution as much as, if not more than, the Hundred Days Reform. Kang's political philosophy that brought him to prominence in 1898 continued to evolve during his exile. His Datong utopian ideas were aimed at a distant future time when China and the world would enjoy a 'universal peace' but, in the meantime, it provided inspiration to future emerging communist leaders. Kang realized, however, that China had to achieve a position of strength before it could enjoy universal peace. It was during the period of his North American travels that Kang made 'a significant shift of emphasis in his social thinking' and what Hsiao Kung-chuan called his 'detour to industrial society'. Experiences in the real world became, for Kang, the means of national salvation for China. The real world he saw in North America included seats of government, factories, mines, prisons, banks, places of learning and worship, restaurants, and entertainment. He conversed with the leaders of such institutions and studied their strengths and weaknesses. Self-government, by which he meant elected by the people, coupled with peace and prosperity, could alone raise China to its rightful place in the world… . Kang Youwei in Canada and the Early Development of Baohuanghui in North America, 1899-1905Zhongping ChenZhongping Chen has shown that Canada and Canadian Baohuanghui leaders played a much larger role than previously understood both in Kang's political evolution and that of his organization. Chen has delved into Canadian newspapers, police reports, and writings by Kang and Canadian members, which reveal that Canadian Chinese leaders often took the initiative from Kang in organizational matters and were entrusted by Kang to travel throughout North American to form new chapters as well as to take control of the Baohuanghui's Commercial Corporation in Hong Kong. Indeed, Chen argues, local community leaders, rather than Kang's closest disciples such as Liang Qichao, Liang Qitian and Xu Qin, founded most of the Baohuanghui chapters throughout the world and certainly were in charge of their subsequent development. Chen thoroughly details Kang's travels throughout Canada on three trips between 1899 and 1905, noting that Kang's own accounts of his travels were 'sometimes misdated, exaggerated, or even fabricated'. Kang's first and second trips, both in 1899, are significant because they shed light on the formation of the Baohuanghui and its future directions. Kang landed in British Columbia on 7 April, intending to visit the US before sailing to Great Britain to seek foreign intervention to restore the Emperor. Since this was the first Western country Kang had ever visited, he was intensely interested in exploring Canadian institutions and within five days had outlined a new, more radical agenda for political reform in China: 'Representative parliamentary government, a system of national banks, state ownership of mines and railways, free education, both elementary and advanced, and including the establishment of technical schools and government seminaries for military and naval training' (Province, 13 April 1899). Chen notes that Kang's speeches in Victoria and Vancouver Chinatowns received such a strong emotional response that Kang realized overseas Chinese were ripe for his political message and eager to tell him their stories of discrimination and suffering as immigrants. Kang also expanded his message as he gained his first experience with the huge audiences of mostly non-elite Chinese, moving from stressing the restoration of the Emperor and Chinese solidarity to promoting good behavior and abiding by Canadian law. Perhaps most intriguing to local leaders was his proposal 'to unite all overseas Chinese through a gigantic commercial corporation.' Soon after Kang left Canada for England, Vancouver Chinese leaders met to plan this corporation and elect officers, duly reported in the local newspapers. Many of the elements of the future Baohuanghui Commercial Corporation were discussed at this time—raising stock from overseas Chinese, opening banks, building steamships, building a railway line in Mexico, and managing the conglomerate from Vancouver. When Kang returned to Vancouver in July 1899, he found a ready-made organization, which he proposed to call Baoshanghui, 'the society to protect merchants'. The names Baohuanghui and Chinese Empire Reform Association were proposed respectively by Victoria leaders Huang Xuanlin and Li Mengjiu. How the organization shifted its aims from commercial to political is not known, but in the programmatic document for the new organization, Kang described it as a corporation [gongsi] and took into account both political and business interests of overseas Chinese. Canadian Baohuanghui leaders also played key roles in the 1900 Qin Wang uprising and in the establishment, operations and funding of the Commercial Corporation. Chen notes that clashes between Kang and Canadian Baohuanghui leaders (especially Ye En) beginning in 1905 would lead to the organization's decline. Kang Youwei and the Baohuanghui in Mexico: When Two Nationalisms CollideEvelyn Hu-DeHartIn May 1911, there was a fatal clash between Chinese nationalism in the form of the Baohuanghui's ambitious business developments in Mexico and Mexican nationalism as embodied in the revolutionaries who stormed the Baohuanghui base of Torreón and carried out 'the single most violent and brutal aggression against the Chinese throughout the America,' massacring 303 Chinese men, among them a close relative of Kang Youwei. Because Torreón was so significant for Kang's fevered rush into business in 1906-1907 and the resulting pressures on the Commercial Corporation and the Baohuanghui itself, Evelyn Hu-DeHart's examination of Mexican archives as well as Baohuanghui correspondence is of special interest. Hu-DeHart described the opportunities that Kang and the Baohuanghui found in Torreón and the consequences of Baohuanghui activities in this city for the organization, the Chinese living there and Mexico itself. She suggests that the very prosperity that the Baohuanghui engendered in Torreón 'probably hastened the coming of Mexico's own revolution'. 'The decision to set up regional headquarters for Mexico in the northeastern city of Torreón, in the border state of Coahuila, probably had a lot to do with the leaders of the Chinese community there, particularly one Wong Foon-Chuck (Huang Kuan Zhuo).' Hu-DeHart has discovered that as early as 1899, Wong began contacting Baohuanghui leaders in Canada, and two of the organization's peripatetic organizers visited Mexico in 1901 (Liang Qitian) and 1902 (Xu Qin), joining Wong in praising Mexico as a destination for Chinese immigration and investment. Torreón in particular was attractive because Mexican state and federal governments were providing tax abatements for investments in modern industry, department stores, and banks. Torreón (caiyuan 菜園 or vegetable garden in Chinese) was also the site of Chinese-owned market gardens, which 'employed upwards of 100 Chinese horticultural workers, and by their sheer size, numbers and location, could not be missed by anyone entering the city.' Chinese became the largest foreign group in Torreón and the most visible. Kang first arrived in Mexico from the US in December 1905 for five months and in Torreón personally 'tested the waters for investment potential, using his own funds to buy up a block of land for 1,700 pesos and sold it several days later for 3,400 pesos, neatly doubling his initial outlay.' Kang and the Baohuanghui moved from stir-frying land to leveraging borrowed funds [from the Chicago restaurant King Joy Lo run by the Baohuanghui] in a new bank, Compañía Bancaria Chino y México (Huamo yinhang), a subsidiary of the Commercial Corporation. The bank was later combined with the most ambitious Baohuanghui investment in Torreón, an electric streetcar line, and the company had its own building downtown. 'Torreón's reaction and response to these highly visible Chinese commercial enterprises were varied and apparently contradictory.' In 1907, Wong Foon Chuck was honored as one of the city's 'founding fathers.' At the same time, a strong anti-foreign and anti-regime movement was building among both local Mexican businessmen and others wanting to end the dictatorship of seven-term President Porfirio Diaz. Kang shared many of the same nationalistic goals as the father of the 1911 Mexican revolution, Francisco Madero, but oblivious to the stirrings of Mexican nationalism and unaware of the danger this might put his compatriots in, Kang made a special trip to Mexico City in 1907 to meet President Diaz. The revolution began in Madero's home state of Coahuila, and most of Torreón's Chinese and the Baohuanghui businesses were among its first victims. Creating Trans-Pacific Students: Kang Youwei and Baohuanghui Schools in North America, 1899-1909Belinda HuangFor Kang and the Baohuanghui, education was 'the foundation of national strength' and an essential part of the organization's program in North America. Distinct from schools set up by other Chinese community groups, Belinda Huang noted that the Baohuanghui network of paramilitary and elementary schools 'introduced Qing current affairs and a new curriculum into the classroom and more explicitly reflected Chinese North America's shift to more national and explicitly political methods of self-identification.' Not unique to North America but also located in Japan, Malaya, Java, Australia and China, the Baohuanghui 'general education' schools emphasized physical education, ethics, philosophical and textual knowledge, and Western science and technology. In North America, these schools also helped children improve their Chinese language literacy, using specially prepared age-appropriate course material. Baohuanghui-funded students were sent to Japan, Europe and the US to study in high schools and universities. Only in Canada and the US, however, were there paramilitary schools, the Western Military Academies (Gancheng xuexiao). 'The 1905 Association convention in New York and the revised constitution placed the "nurturing of human talent" [yucai 育才] and "military spirit" [shangwu jingshen 尚武精神] prominently on the agenda.' Further on, the constitution reads: 'those willing and inspired youth who enroll in the Academy must courageously and robustly develop their full potential in the hopes that, one day, they will defend our country… . After three years of study, the regional branch and the local principal can select and enroll the promising students into American military schools to prepare as future commanders and leaders. Their costs will be covered by the head office.' Huang says that in fact the Western Military Academies 'were military organizations modeled on the American armed forces'. 'The organizers [generally American veterans but also the self-proclaimed 'General' Homer Lea] often disguised the extent of their military operations because it was illegal to train with actual weapons in Canada or the United States,' and 'the students were expected to serve in the Chinese Reform Army (Zhongguo weixin jun) in China.' As many as 2,100 men in more than twenty cities, many of them low-paid restaurant and laundry workers, contributed fifty cents a month to learn 'military science and tactics', often drilling with weapons behind closed doors or performing outdoor maneuvers in remote places. The Academy students, Huang said, were 'cultural brokers' whose 'displays of marching expertise [in American parades] earned them rare positive portrayals and begrudging praise in the usually hostile mainstream English-language media.' At the same time, because of their exposure to non-Chinese culture, 'they self-identified as 'Chinese' before most of their compatriots in China.' Kang is said to have written the Academy's song which linked the students to China's future, by calling on them to 'revitalize our Middle Flowering Realm [wo Zhonghua 我中華]' and 'to defend the nation [weiguo 衛國] without wavering and forget all poverty and hardship.' Huang believes these paramilitary schools were 'the first successful trans-North America effort to include young people in Chinese politics': During [the military schools'] peak from about 1900 to 1905 they created a new focus and activity for young Chinese men in major North American cities to participate collectively, for the first time, as militant, active, 'Chinese' men... . Participation in the army simultaneously encouraged the youth to take pride in their dual connections to China and North America. The students were encouraged to see themselves as the next generation of leaders who would build a more powerful China and improve their collective lives in North America. |