|

||||||||||

|

T'IEN HSIAThe '中国通' or the 'Sinophone'? Towards a political economy of Chinese language teachingEdward McDonald School of Asian Studies, University of Auckland

In 2010, a discussion developed in the People's Republic related to the concept among some academics of the need for China to articulate a theory and practice of what they have termed 'national strategic language' (Guojia zhanlüe yuyan 国家战略语言). A grant program at the Shanghai International Studies University has been devoted to the study of foreign language development strategy. Joel Martinsen, of Danwei, published a translation of one of the first semi-academic 'outputs' of the grant that appeared in October 2010 in the Global Times. The author of this essay which was originally a blog post, Zhang Wenmu 张文木, is a professor at the Centre for Strategic Studies, Beijing University of Aeronautics & Astronautics. Among other things, his argument states that, 'If we wish for the world to know and understand China, as we promote the national language, we must step up the formation of China's strategic language and its use on a world stage.' In relation to linguistic diversity and difference within the territory of the People's Republic, Zhang goes on to say, 'A "Chinese language" based on the "Han language" family can be fashioned to occupy a higher position domestically than the "dialects" of ethnic groups, and to express a uniform national strategic language recognized by all the people of China internationally.' Although he does counter this by saying, 'It must be pointed out that fashioning a national strategic language elevated above the dialects does not imply that dialects must be wiped out. Corresponding language policies should include the preservation and enrichment of the diversity of dialects, and the protection and elevation of the primacy of the Chinese language.' Zhang's argument and the concept of a 'national strategic language' are debated among specialists and others in China. As party-state pressures to impose ever-greater conformity on the languages, writing systems and uses of the People's Republic, it is timely to add to our own discussions of New Sinology in the present issue of China Heritage Quarterly by publishing a recent work by Edward McDonald, a specialist in the field of Chinese linguistics. Also in this section we feature Frederick W. Mote's observations on the building of a successful East Asian Studies program at Princeton University.—The Editor A New Sinology, or a more profound and humanly rich engagement with China and the Chinese world, is not a study of an exotic, or increasingly familiar Other. It is an approach that also constitutes a concerted attempt to include China as integral to the idea of a shared humanity in all of its contradictory, unsettling as well as inspiring complexity. It is a study, an engagement, an internalization that enriches the possibilities of our own condition. … Nor is this merely an engagement in one direction. For to talk of some divide, some chasm that has to be bridged or crossed, is to accept too easily the belief that difference predominantly creates barriers and distances. It also limits us unnecessarily to the idea that studying about China, learning its languages, cultures and thought systems is to limit ourselves to being interpreters of a 'correct' view of what China and Chineseness is. While such linguistic and cultural translation is essential for the growth of all peoples, our engagement with China is not merely that of sophisticated interpreters equipped through dint of hard work and long years of study with some privileged insider knowledge. —from Geremie R. Barmé, 'China's Promise'[1]

In an increasingly globalised world, more and more people with a personal and / or professional relationship with China are crossing the divide between the 'Chinese' and the 'Foreign', so long taken as an unquestioned given, and transforming it irrevocably in the process. The field of Chinese studies, however, that academic and pedagogical enterprise with the task of facilitating entry into the sphere of the 'Sinophone', remains largely locked into a reductive binary whose two poles are those of Sinophone China and Anglophone America, where it is in the ideological interests of both sides to stress separateness and incommensurability. This essay develops an argument put forward in my book, Learning Chinese, Turning Chinese: challenges to becoming sinophone in a globalised world[2] where I pose a crucial question: How well does the field of Chinese Studies face up to the needs of 'potential sinophones', that is university students currently studying Chinese or intending to do so. In the book I suggest certain trajectories over the 'Great Walls of Discourse', to use Haun Saussy's phrase, currently separating China from the rest of the world.[3] The general approach taken is summed up in the Introduction: The English word Chinese is multiply ambiguous, corresponding to Zhōngguó (de) 'related to China', or Huárén (de) 'related to Chinese ethnicity' or Zhōngwén (de) 'related to Chinese language'. It was no doubt for this reason that in recent years within Chinese Studies the third of these meanings has received a new English coinage, sinophone. In this book, however, rather than using sinophone to refer just to 'Chinese language', I have chosen to give it a broader connotation, playing on its etymological meaning of 'Chinese voice'. …As a potential sinophone, you yourself must develop your own Chinese 'voice', quite literally in terms of mastering the sounds and wordings of the language, but also in the sense of finding an identity for yourself, of establishing a reference point for yourself in the sinophone world. In the course of this process, you will obviously talk with and learn from others, in the first instance your teachers and fellow-students, and then the widening circle of Chinese speakers with whom you come into contact. After a while you will begin to assert yourself as a sinophone, to intervene in the dialogue, to put forward your own point of view, and to take issue with others' points of view.  Fig.1 Kunming street The term 'sinophone' seems to have been coined separately and simultaneously on both sides of the Pacific: by Geremie Barmé in his 2005 essay 'On New Sinology';[4] and by Shu-Mei Shih in her 'Sinophone Articulations Across the Pacific',[5] and developed at greater length in a book by the same author.[6] In Shih's usage, where the writer concentrates on the fields of literature and visual communication, and following a similar usage of the term francophone in French, the term is restricted to 'Hanyu and other Chinese language speaking communities outside China' (my emphasis). In a review of Shih's book, Sheldon Lu criticizes such a restriction as unworkable and unnecessary: The Sinophone is defined as 'a network of places of cultural production outside China and on the margins of China and Chineseness, where a historical process of heterogenizing and localizing of continental Chinese culture has been taking place for several centuries.'[p.4] 'The Sinophone, therefore, maintains a precarious and problematic relation to China, similar to the Francophone's relation to France…'[p.30] The Sinophone is a counter-hegemonic formation against China-centrism and a deconstruction of essentializing notions of 'China' and 'Chineseness.' The exclusion of China itself from the domain of the Sinophone may seem liberating and progressive at first glance in academic discourse; but ultimately, this is unsound theoretically and inaccurate empirically. A major theme throughout Shih's book is the ineluctable condition of transnationality in the Sinophone region at the present historical juncture. But does transnationality in the Sinophone region only gather momentum in Hong Kong and Taiwan, and stops [sic] short of crossing the Chinese border? The transnational is by definition border-crossing. China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the Chinese diaspora are mutually imbricated in the globalizing world. The concept of 'Sinophone' loses its critical edge in this exclusionary approach to China and the Chinese diaspora. If we have to use this imperfect label, the Sinophone would include all Chinese-speaking communities in the world, including, not excluding, China itself.[7] If the Sinophone is to include all Chinese-speaking communities around the world, it is not then a great leap to include within its scope also those from a non-Sinophone background coming to the learning of Chinese, and ultimately becoming part of Sinophone culture. Hence, in my work, extending both Barmé and Shih's usage, the term Sinophone is used not simply descriptively, as an adjective equivalent to 'Chinese language', but also as a noun, referring to a kind of role or identity, one that I argue should be taken on as an essential part of the process of learning Chinese. The term 'Sinophone' has already received the ultimate contemporary accolade—being included in Wikipedia—whose definition indeed reflects this broader usage: Adjective From the point of view of language learning, the traditional notion of 'learning Chinese' can be re-conceptualised within a more inclusive goal of 'becoming Sinophone'. As to what exactly those studying Chinese should be aiming for in terms of skills and knowledge, I would claim, along with many scholars of Chinese and of language learning more broadly, that the goal for the potential sinophone should be not simply the relatively passive acquisition of knowledge, but rather an active development of a Chinese-speaking identity: in other words, in order for the process of 'learning Chinese' to be successful, it must also involve a parallel process of 'turning Chinese'. And as Geremie Barmé points out, this necessarily also includes an 'enmeshment with the Chinese world', as well as an understanding not just of the dynamic present but of its 'complex origins' and its 'possibilities for tomorrow': In thinking about Chinese realities, we are concerned not only with the issues of the day but also with the complex origins of those realities and the Chinese possibilities for tomorrow as well. Just as the Anglophone world—that is the linguistic realm that started out limited to the British Isles—has become part of world culture, as have French and Spanish and Arabic, the Sinophone world is likewise one of global reach. Its 'hybridity' adds to lives, thinking and feelings wherever it extends. I believe that we, and more importantly, those who are being educated in Chinese now as well as those who will be literate in Chinese in the future can and will be co-creators in this process. Young people—no matter of what ethnic or multi-ethnic background—are and will be part of this extraordinary new era of human engagement in which Chinese languages and cultures are increasingly part of the global world. … Writing, thinking and creating in Chinese, not as merely passive receptors, not just to be told tirelessly what 'We Chinese' think, is, I would suggest, part of the way that a developing enmeshment with the Chinese world is already unfolding for many young people.[8]  Fig.2 Beijing traffic There is an ideological complex deeply embedded in the field of Chinese language teaching and China-foreign relations more broadly, however, a syndrome for which the language functions as the ultimate gatekeeper, which suggests that foreigners trying to learn Chinese are in effect wasting their time: that the language is too 'difficult' or the culture too 'different' for those coming from outside the Sinophone sphere ever to succeed in being admitted into it. This kind of cultural exclusionism is simply the other side of a political exclusionism—the felt need to keep foreigners from penetrating the inner circles of the Chinese sphere—which reflects the threatened stance of China towards the rest of the world since the Opium Wars of the 1840s, and whose most recent manifestations might be called the China Can Say No school of thought.[9] This syndrome also finds expression in a 'Keeping Chinese for the Chinese' kind of cultural exceptionalism—a strongly held ideological position that China and its culture cannot be treated on a par with other countries and cultures—one of whose main manifestations is the discursive phenomenon I have dubbed 'character fetishisation', that is, an inordinate if not hegemonic—to use an appropriate political metaphor—status assigned to Chinese characters in the interpretation of Chinese language, thought and culture.[10] This ideological complex, though ultimately based on Western misconceptions of the Chinese writing system, and still firmly held by many (foreign) sinologists, has become nativised among Chinese scholars and been fed into discourses of cultural nationalism more broadly, where it is put to political work arguing for the uniqueness of the Chinese situation as part of the exceptionalist ideology of so-called 国情 or 'national characteristics'. In Chapter 6 of my book, in a discussion of language reform which addresses in a linguistic context the still unanswered question of modern China–whether modernization can take place without Westernization—I comment perhaps somewhat facetiously on this defensive mindset, in a comparison of the discourses of political and cultural nationalism which are such a prominent feature of the contemporary scene: Both these political and cultural nationalisms argue, in effect, for the need to treat China as a special case, a theme that goes back to official Mainland rhetoric of the 1970s and 1980s about Zhōngguó guóqíng 中国国情 or 'Chinese characteristics'.[11] Both are manifestations of a continuing and uneasy accommodation in Chinese political and intellectual circles to the 'decentring' of China since the incursions beginning with the Opium Wars of the 1840s. The unfinished nature of this accommodation is aptly summed up in the superficially neat division of labour recommended by the late Imperial reform slogan Zhōngxué wéi tĭ, Xīxué wéi yòng 'Chinese learning as essence, Western learning as application'. The problem is that after the huge foreign borrowings of the intervening period, borrowings which have fundamentally transformed Chinese culture, no-one is quite sure any more exactly what the 'Chinese essence' might look like, a paradox reflected in the schizophrenic worldview of both Chinese Cultural Linguistics and popular nationalistic rhetoric.[12] In a recent study, William A. Callahan sees such a schizophrenic worldview as defining of China's view of itself in relation to the rest of the world, to the extent that he dubs China a 'pessoptimist nation': To understand China's glowing optimism, we need to understand its enduring pessimism, and vice versa. To understand China's dreams, we also need to understand its nightmares. China's national aesthetic entails the combination of a superiority complex and an inferiority complex. Rather than being opposites, in China, pride and humiliation are 'interwoven, separated only by a fine line and can easily trade places.'[13] He further comments on the need to see the personal and the institutional as tightly interwoven: Rather than simply being 'a land of contradictions' that suffers from 'national schizophrenia,' I think it is necessary to see how China's sense of pride and sense of humiliation are actually intimately interwoven in a 'structure of feeling' that informs China's national aesthetic. 'Structure of feeling' is a useful concept because it allows us to talk about the interdependence of institutional structures and very personal experiences. Given this simultaneous yearning for and fear of the foreign, it is not surprising that the field of Chinese language teaching, that channel above all whereby the foreign is brought into a potentially intimate relationship with the native, should exhibit a simultaneous welcome and exclusion of the foreign learner . Moreover, given that this schizophrenic worldview is part of a pervasive 'structure of feeling', it is hardly surprising that it should be largely unconscious and resistant to analysis. Such 'Great Walls of Discourse', then, although on critical analysis proving to be based on rather flimsy foundations, nevertheless permeate not just the formal pedagogical apparatus of textbooks and descriptions of the Chinese language but also the mindset of many teachers of Chinese, creating a rather dispiriting and demotivating atmosphere for the potential sinophone seeking entry into the sinophone sphere. Moreover, the peculiarities of Chinese language teaching project are embedded in and cannot be understood apart from the strategies developed over centuries by the Chinese state for managing foreigners inside China, whereby the state assumed the responsibility for looking after foreigners: keeping them happy, if possible, but above all keeping them separate. Jane Orton sketches in the historical background here and its implications for Chinese learning foreign languages, implications which are also relevant for foreigners learning Chinese: The Chinese ambiguity in attitude towards foreigners…pre-dates Western contact, although it became considerably more specifically directed at English speakers once British gunboats arrived in Chinese waterways in the mid-19th century. Adamson calls it 'ambivalence' and explains it as 'a strategy' to deal with the consequences of the foreign invasion.[14] Major among these, were a threat to the quintessential Confucian belief in the superiority of Chinese culture in a naturally hierarchical world, and the fundamental preference of the Chinese for national insularity.[15] From this perspective, the arrival of the armed invaders in the mid-nineteenth century can be seen to have faced the Chinese with what Giddens calls 'a fateful moment': a transition point where consequential decisions to launch out into something new, once taken, have an irreversible quality, or at least it will be difficult thereafter to revert to the old paths.[16] The Chinese response to their fateful moment was a decision to 're-skill', and thus they set out to 'learn the superior skills of the barbarians in order to control them' (Wei Yuan 1842).[17] The means to this end were 'a controlled and selective appropriation' of the source of the foreigners' power. The source was a new type of knowledge, clearly separate from much of Chinese knowledge, which they believed could be learned and still kept separate by those already educated in Chinese knowledge. Thus the framework for learning was to be 'Chinese ethics and Confucian teachings…as an original foundation…supplemented by the methods used by the various nations for the attainment of prosperity and strength' (Feng Guifen, 1861).[18][19] Such strategic accommodations, however, are difficult to confine within their original utilitarian boundaries; by their very nature they transform the identities of those who engage in them: As Giddens, however, points out, while deciding to re-skill/appropriate may allow learning about options available, decisions on what to choose from among the new options are more difficult to make. Furthermore, these are not simply behavioural options: they tend to refract back upon, and be mobilised to develop, the narrative of self-identity [21]. And, indeed, from the start, as each option taken refracted back upon the Chinese narrative of self-identity, one consequence of which was that the perceived source of foreigners' power would then shift. To this day the targeted source remains elusive in definition and role, and never more so than in its relationship to language.[20] The enduring nature of such managing and containing strategies is very clearly indicated in the most inclusive term for foreigners in contemporary popular parlance: the waiguo pengyou 外国朋友 or 'foreign friend' (corresponding to the guoji youren 国祭友人of official discourse), both being quasi-diplomatic terms which in the way of much diplomatic language carry more than a hint of euphemism—the foreigners will be (made to be) friendly, whether they like it or not! More colloquially, foreigners are often dubbed Lao wai 老外, literally 'old foreign', where 'old' is traditionally a term of respect; but the ambiguities of this term may be gauged in the first instance from the fact that colloquially the term is also equivalent to waihang 外行, someone who by being 'outside' the 'profession' is ignorant of its key understandings and expected behaviours; and by the fact that it is not all foreigners who qualify as 老外. In common usage, 老外 tends to refer mainly to Westerners, those foreigners whose wealth and power makes them worthy of respect, as opposed to, for example, the much less complimentary term Lao hei 老黑 'Old Black' whose connotations almost approach those of the thankfully no longer contemporary English term 'darky'.  Fig.3 Gate lion Such questions of terminology are as good a place as any to start our exploration of these complex cross-cultural journeys in which the potential sinophone will be involved. The entry point for most foreigners looking for a sustained and ongoing relationship with the sinophone sphere is through the Chinese teaching profession: specifically that part of it known in Chinese as 对外汉语教学 or 'teaching Chinese to foreigners'. In contrast to the terminology common in English language teaching, where the kind of teaching and learning is subclassified by the place of study–either 'as a second language' where it is taking place in an anglophone environment, or 'as a foreign language' in a non-anglophone environment, the Chinese term 对外 'towards foreign' stresses rather the foreignness of the targets of teaching and learning. This does, I think, reflect a still very sinocentric attitude on the part of the relevant official institutions such as the Hanban 汉办 (Guojia duiwai Hanyu jiaoxue lingdao xiaozu bangongshi 国家对外汉语教学领导小组办公室), which goes under the rather clunky English title of 'Office of Chinese Language Teaching International', but whose Chinese title includes this 对外 'towards foreign' element, institutions which tend to regard any interaction taking place as operating in an exclusively unidirectional way outwards from the presumed 'centre' of the sinophone sphere to the eager foreigners gathered at its gates. While an enviable expertise in teaching Chinese as a second language has been built up over half a century through such educational institutions as the Beijing Language and Culture University, formerly the Beijing Languages Institute, or the Mandarin Training Center at Taiwan Normal University (formerly the Center for Chinese Language and Cultural Studies), with regard to the teaching of Chinese outside the sinophone sphere, the developments necessary to make this far more complex endeavour equally successful are still largely waiting to happen. This situation has recently been pointed out with great force and cogency by a voice from near the centre, but historically often a source of dissent, Peking University. Doyen of modern Chinese grammatical studies, Professor Lu Jianming 陆俭明 of the Chinese Department of Peking University, at the time an advisor to the Hanban, starts out by advertising the change that is currently at least being recognized: The new trend in contemporary Chinese language teaching is to change from the past practice of walking on one leg to one of walking on two legs: that is, in the past it was a case of 'please come in' (请进来), whereas now alongside the continuation of 'please come in', we also need to 'go out' (走出去), so that 'come in' and 'go out' run side by side.[22] Lu's comments come from an extended discussion on the need for developing new teaching materials to suit the needs of students of Chinese as a foreign language, and he comes at these issues professedly as the linguist that he is, skilled at highly detailed and delicately nuanced treatments of contemporary Chinese grammar: his analysis is thus in effect based on a close 'reading' of current textbooks in relation to the needs of teaching Chinese to foreign learners. Lu is nonetheless well aware of the broader context in which these developments are embedded; and he goes on to raise the crucial question of what exactly is the motivation for this new phenomenon of 'going out', for creating this new profession of what he dubs Guoji Hanyu jiaoxue 国际汉语教学 or 'international Chinese language teaching': The aim for us in developing the work of international Chinese language teaching is to construct a bridge of friendship—a Chinese language bridge [Hanyu qiao 汉语桥]—for all the countries of the world, to strengthen friendly relations and economic and cultural contacts between our country and all other countries, and to create a harmonious international environment; on the other hand, not to mince words, it is to allow our brilliant and profound Chinese culture to blend into the big international multicultural family, and to contribute our strength to the establishment of a harmonious international order; and at the same time to gradually resolve the problem of the discursive rights [huayu quan 话语权] of Chinese internationally. Professor Lu is completely frank about the geopolitical context of what from this point of view he very appositely terms international Chinese language teaching, and about the linguistic and cultural economy in which he sees China taking its rightful place. But he is also realistic about the complexity of the task before the Chinese teaching profession if a truly 'international' version of Chinese language teaching is going to be able to successfully contribute to these aims: Teaching Chinese as a Second Language is a cross-disciplinary field involving among others the linguistics and graphology of Chinese, applied linguistics, educational theory, psychology, literature, culture, and art. To put it another way, Teaching Chinese as a Second Language is a science. And to science one must take an honest approach, there is no place for the slightest boastfulness or impulsiveness. And he is adamant that this science above all relies on (inter)personal interaction between teachers and students: In Chinese teaching we must certainly make good use of advanced information media such as the multimedia web, but however advanced the multimedia web it cannot completely replace the function of a Chinese teacher in providing personal instruction, nor is it a substitute for the positive influence of the special attraction a Chinese teacher brings to students. A recent 'state of the art' summary of the field by Janet Zhiqun Xing, also stresses this interpersonal aspect of its participants: referred to by Xing as 'Chinese language practitioners', defined as 'teachers and students of Chinese as [a] F[oreign] L[anguage]' who are seen to share many common goals, as she explains using a domestic metaphor: Although the members of these two categories of language practice vary in terms of status/position, attitudes and personality, they engage in activities that are very dependent on goals: to teach or learn communicative skills in the target language. These two members function as if they are a married couple practicing the Chinese language. Both of them have to work hard, learn from each other and cooperate with each other to create a harmonious environment so that teachers become skilful in teaching and students become knowledgeable and competent in communicating in Chinese.[23] The characterisation of teachers and students as forming a family immediately calls to mind the Confucian world-view, which takes the hierarchically ordered family as the model for all other forms of social organisation—though given the male-female inequality deeply embedded in that world-view, one might want to ask which is the husband and which the wife in this little scenario?—and at the same time fairly accurately reflects Sinophone cultural norms, including those of the language classroom. But whether such a model is necessarily going to be appropriate in the non-Chinese contexts to which the term 'foreign language' specifically refers is a question that is only just beginning to be raised, whether in Xing's book or in the Chinese teaching profession more widely. The geopolitical complexities of bringing the teaching of Chinese as a foreign language to the world, an endeavour whose most obvious recent manifestation is the setting up of Confucius Institutes around the globe, is a whole other topic in itself that deserves extended study. What I would like to explore further here are some of the interpersonal complexities touched on by Lu and Xing, specifically with regard to the role of the student. While the Chinese teaching profession, so far at least, has not had much to say about the specific situation of the foreign student learning Chinese outside China, once the student arrives in China he or she is immediately fitted into a particular slot in the elaborated system that has been built up over the last half century for managing foreigners within China: that of the 留学生, literally the '(temporarily) staying student'. This classification was first applied to Chinese students studying overseas, who from the closing years of the Qing Dynasty went to Japan, America and Europe to acquire the modern skills and knowledge their country so desperately needed, after which they would return to China to contribute to its 'self-strengthening'. The paradoxes of this process may be gauged from the ambiguous status of their contemporary equivalents, the so-called 海龟 or 'turtles', punning on the homophonous 海(外)归(来) '(those) returned from (over-)seas', whose challenges in readapting to 中国国情 'China's national characteristics' and the notorious complexities of its 人际关系or 'interpersonal relations' are well documented. In the case of foreigners studying in China, the whole point of being a 留学生 is that the process of 留 or 'staying' is strictly a temporary one: studies concluded, the student is supposed to return to his/her place of origin. So what happens to the 留学生 who continues to留? While the official classificatory system is silent on this point, it does provide slots for those 'foreign friends', Chinese-speaking or not, who choose to stay in China. The first of these is, as it were, the adult equivalent of the 留学生, the 外国专家 or 'foreign expert' (its usual translation, though 'specialist' would probably be closer to the mark). Like the (外国)留学生, the term 外专, as it is known for short, indicates a strictly temporary status: foreign experts are supposed to come to give China the benefit of their expertise—in the equal and opposite function of Chinese studying 'Western learning' overseas—and once having 'transferred' the relevant 'knowledge', they should then return to their home countries. Jane Orton reflects on her own experience as a foreign expert near the beginning of the Open Door period, and the frustration she felt at the limited kind of interaction that was expected of her then: The Chinese government rhetoric of 1981 positioned native English-speaking teachers working in China as people valuable in the Chinese quest—foreign experts and friends of China—but it also im-positioned them as little more than respected sources of authentic English language and meta-linguistic knowledge; and this was largely how they were treated by the groups of students and teachers they worked with. Texts of all kinds were deconstructed into turns of phrase and linguistic structure which they were to explain, but the thrust of their content as grist for thought was ignored, and attempts to attend to this level of meaning positively resisted. There was, it seemed, little interest in what the English speakers knew and valued about themselves and their societies and cultures, nor in what they were critical about or worried about with regard to them. It was as if, having found a ship anchored along a river bank, people wanted to seize the vessel and dismantle it into decking planks, brass door handles, pieces of the steel hull, etc. to be stored for later use. There was no interest in the sailors' stories of the risks and joys of voyages at sea, and no awareness at all of the human curiosity and spirit of adventure which had led to the ship being built in the first place.[24] And she reflects further on how China's needs cannot be met by such a limited understanding of exchange, a situation again with clear implications for the foreign learner of Chinese: Accessing knowledge one cannot yet recognize as such is possible only with the help of an insider; and if any help offered is to be usable, the insider will need the seeker's assistance. Or, as Giddens would put it, the narrative of self-identity which China seeks to develop through its contact with English speakers, cannot be affirmed and developed simply by 'recognising the other', however respectfully. Instead, it can only be negotiated through linked processes of self-exploration and the development of intimacy with other [25].  Fig.4 Multilingual polity Another classification mentioned by Orton, not so common now as in the days when China was largely shut off against the capitalist—and 'revisionist' communist—world, is the中国人民的老朋友 or 'friend of China'—literally 'old friend of the Chinese people'. This term was most commonly applied to the 'old leftists' or companions of the revolution whose identification with the aims and ideologies of the Communist state meant that they were able to remain in mainland China when most of the resident foreigners were expelled after 1949, or were allowed to enter in the period of the 1950s to 1970s when most foreigners were excluded: including such people as New Zealander Rewi Alley (whose case has been insightfully described by Anne-Marie Brady [26]), Britons Isabel and David Crook, and Gladys Yang (married to Yang Xianyi), Lebanese-American George Hatem, Canadian Norman Bethune, Pole Israel Epstein and so on. Such 'friends of China' seem to have become so largely through being at odds with their own countries of origin, or at least with their countries' political systems, and by being absorbed into the all-consuming and unidirectional project that was the 'socialist construction' of the 'New China'. As put by Brady, 'resident friends of China were as much linked by displacement from their own societies as they were by a strong ideological commitment to Chinese communism'.[27] Although, as documented in Brady's study with the significant title Making the Foreign Serve China, the role of these foreign friends was of some importance at the time when China felt itself to be largely surrounded by foreigners who were almost all by definition enemies, with the opening up of the Chinese economy and the concomitant refocusing from 'socialist construction' to 'economic construction' the role of such ideological fellow-travellers is now largely of historical significance. A different kind of classification, applied mostly to foreigners studying China rather than studying in China, is the second of the terms included in the title of this paper 中国通: literally one whose knowledge of China is 通 'thorough-going', 'complete' or 'comprehensive'. Many an (ex-)留学生 will have had the experience of this term being flatteringly or jokingly applied to them—often in situations where it functions as a polite nothing, largely equivalent to its linguistic counterpart 你中文说得不错 'Your Chinese is very good'— in both of which cases the compliment is often far from warranted on the basis of any actually demonstrated knowledge or skill! (In both cases the expected response is a modest 哪里哪里 'not at all' or 还差得远 'far from it'.) A quick search of the Chinese search engine Baidu reveals that the term中国通 is normally understood as having a number of connotations:

The representative example given here is a certain 陆克文, better known outside China under his original English label of Kevin Rudd. I discuss below Rudd's positioning of himself in relation to China, in particular his strategic employment of the discourse of 诤友 or 'true friend' (literally a 'critical friend'), and suggest this shows him to be a functioning sinophone rather than (merely) a 中国通. To conclude its explication of the latter term, Baidu provides a couple of further definitions which specifically contrast knowledge of China with proficiency in Chinese:

After this brief trawl through the most commonly-used expressions for foreigners involved with China, we might sum up the main assumptions of the current classifications as follows:

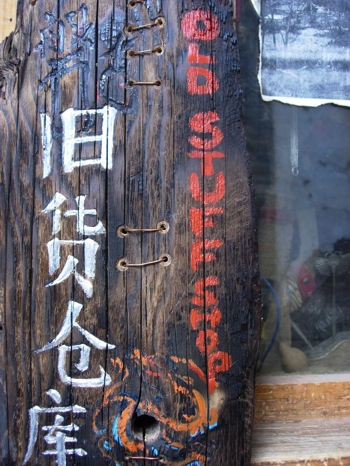

I would like to suggest that not only do such cut-and-dried categories fail to reflect the dynamic exchange and self- and other-transformation that are now increasingly taking place, they also place restrictions on the conceptualization of China-foreign interactions that will prove counterproductive to any genuine and long-term engagement. I will do this in the first instance by contrasting these two terms: sinophone and中国通. My initial context for bringing these two concepts together was an informal discussion with Professor Gao Yihong 高一虹, Director of the new Research Centre for Linguistics and Applied Linguistics in the School of Foreign Languages at Peking University, and some of her postgraduate students, to whom I had shown the Introduction to my forthcoming book. In discussing this new term 'sinophone' in the sense I am using it in my book, they raised the question of whether its Chinese equivalent should be 中国通. The following analysis draws on that discussion, as well as on some follow-up email exchanges between Professor Gao and her students that were sparked by it. My feeling was that the two were not equivalent: that 中国通, if not simply an empty compliment, as if in surprised acknowledgement that a foreigner should know anything about China at all, but rather applied in a substantive sense, still had very different connotations and indicated a quite different emphasis from sinophone. To sum up what I see as their main difference, 中国通 is above all a knowledge-based notion, it emphasises the accumulation and mastery of knowledge; sinophone, on the other hand, while including knowledge of language and culture as an essential component, is above all a pragmatically-oriented notion, it emphasises the ability to enter into Chinese-speaking societies—in short it is a contrast between 通 'cognitive understanding' and 顺 'behavioural accomodation'. As summed up by one of the participants: To become sinophone [foreigners] must certainly understand something about Chinese customs and interpersonal relationships, but that is only to help them understand the ways of using the language, not to be expert on Chinese culture as such. The same participant suggested that sinophone had very much an instrumental emphasis, and that the question of what kind of identity such foreigners possessed was much more of an issue for their Chinese 'hosts' than for the foreigners themselves: Sinophone is not necessarily an identity, although foreigners (老外) getting by (混) in China must face the issue of identity—this issue is perhaps more one raised by Chinese, and doesn't really exist as an issue for the person who really wants to become sinophone. Sinophone has a stronger implication of ability. Another participant suggested that the earlier classification中国通 was a product of a historical set of circumstances that no longer applied: '中国通' arose in a situation where the cultures of the world were cut off from each other, at that time '通' was an amazing thing. Now '通' is gradually becoming a trend, what Lao Ma [my Chinese moniker] is talking about is actually just in certain areas 通而不同 'understand but not be the same', to maintain your own viewpoint, standpoint, lifestyle, and refuse assimilation. In an article published in the same collection as Orton's quoted from above, Gao comments on the complexities of becoming part of another culture through learning the language, drawing on French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu's notion of habitus, that system of dispositions, of lasting acquired schemes of perception, thought and action which provide the basic meaningful context for the individual to make sense of his or her experience, a system in which language of course plays a key role: The learning of a foreign language involves acquiring a habitus that may be perceived to clash with the learner's first language habitus, and . . . this has generated prolonged identity anxiety among Chinese involved in learning English. The solution to easing this anxiety has been to nominate Western learning as yong (utility) only and thus to focus on the economic value of the language as capital. Yet, because there is always cultural ti (essence) embedded in linguistic habitus, attempts to separate yong from ti in the learning of English and other languages have not solved the problem. Instead, there has been a recurring ti-yong tension, which has highlighted the fundamental identity dilemmas in China's English language education. Furthermore, in contemporary China, where English language education itself has developed into a semi-autonomous field in the context of globalisation, the persistent ti-yong dilemma has acquired increased intensity and complexity.[28] Gao's analysis recalls that of Lu quoted above, and raises some very pertinent questions for the internationalisation of Chinese language teaching and the situation of the potential sinophone. In this regard, Jane Orton identifies a deeper cultural divide that complicates Chinese attempts to come to terms with the Western worldview, as for example in attempting to adapt Western student-centred communicative language teaching methodologies to the teacher-centred Chinese classroom. Orton comments on the Western focus on the 'individual', conceptualised as 'one who has a right, even a duty, to be an agent in the world, one who can and should introduce change (for the better) through his/her own action', and how the individual is 'created' through a process of behavioural training that starts from the very youngest age: Socialisation into such a way of perceiving and behaving starts at least as early as the first week after birth, when, for example, a baby born into an English speaking family is left to sleep in its own cot, in its own room, and even at times allowed to cry there alone [to the intense distress of any Chinese visitors]; and the process is continually if casually fostered by parents and teachers, who do not simply command obedience—'Put that down!', 'Look at this', 'Go and do that'- but present the world as a series of interrelated, causal events in which the child is one of the active agents—'If you ask Mrs Jones nicely, I am sure she would let you play with the dolls'. 'If you touch that, you'll get hurt!' 'If you look at it carefully, I am sure you can work out where it goes.' 'And what would you like to do?' 'Which one would you like to choose?' The focus is generally on macro level learning—problem-solving—rather than items of information, and error and minor injuries are accepted as inevitable and useful elements in the process of growth.[29] There is thus a very different understanding of 'self-construction' that underlies the 'theory of action' in each case: [I]n Western eyes, mature moral orientations and the criteria that underlie dominance and submission patterns are always in a contradictory relationship.[30] Congruently, the rights to be taken by the Western self are accompanied by a concomitant responsibility as an essential co-part of self-construction. Hence the behaviour which may appear in Confucian terms to be an unjustifiable privileging of self[优越感], in the terms of the other will often appear as taking responsibility for oneself [责任感], a central element in Western moral education and in good Western work practices, including teaching. These contradictions at core mean that the theory of action by which each form of self-identity is realised in the modern world is very different. The result is not only that the forms are often antagonistic, but that the resulting surface clashes are hard to resolve because the beliefs, values and practices of the theory they cohere in are often known only tacitly by the one side, and are simply invisible to the other. In this predicament, certain aspects of Chinese re-skilling comprises a binary struggle between a total laminate of imported practices, laying the new over the old so as to all but suffocate what lies below—a process, not surprisingly, resisted; and a 'sinicising' of the new to make it fit more comfortably with the old–a move that, in fact, robs it of the very power it was borrowed to create. Rarely in the contested areas is there sufficient clarity of what is at stake to develop the graft, which any hope of success would require.  Fig.5 Old Stuff Shop To continue Orton's horticultural metaphor, I would argue that the potential sinophone needs to enter into a process of hybridization, that the purpose of Chinese studies should be precisely to create such cross-cultural hybrids, able to move between cultures and feel at home in each, and that their value to themselves and their societies then stems from their ability to mediate between different cultures. In an earlier article discussing language learners' development of 'intercultural communicative competence', Gao puts forward a distinction between 'going across' and 'going beyond' in approaching the target culture, where the former 'focuses on the increase of target culture proficiency', while the latter 'focuses on the gaining of cultural awareness and reflective tolerant attitudes'. Gao sees the latter as to be recommended for the language learner, a process which involves three main cognitive and socio-cultural transformations:

The implications of this analysis for the current discussion are that such a project requires a personal transformation on the part of the potential sinophone, one which involves an open and non-judgmental attitude towards both the source culture and the target culture and avoids the pitfalls of cultural stereotyping and essentialism.[32] It is in this context that I would like to finish up by discussing that imputed 中国通 par excellence, 陆克文, Kevin Rudd, and his strategic intervention into the Australia-China relationship through his invocation of the discourse of 诤友 or 'true friend'. I noted above that the most inclusive term for foreigner in contemporary Chinese parlance is 外国朋友or 'foreign friend'. Geremie Barmé explains the historical context of this usage: [T]he…word 'friendship' (youyi) has been a cornerstone of China's post-1949 diplomacy. Mao Zedong once observed, 'The first and foremost question of the revolution is: who is our friend and who is our foe.' To be a friend of China, the Chinese people, the party-state or, in the reform period, even a mainland business partner, the foreigner is often expected to stomach unpalatable situations, and keep silent in the face of egregious behaviour. A friend of China might enjoy the privilege of offering the occasional word of caution in private; in the public arena he or she is expected to have the good sense and courtesy to be 'objective', that is to toe the line, whatever that happens to be. The concept of 'friendship' thus degenerates into little more than an effective tool for emotional blackmail and enforced complicity.[33] Barmé explains how Rudd, in a speech at Peking University in April 2008, chose to 'deftly sidestep the vice-like embrace of that model of friendship by substituting another': Rudd then spoke about China joining the rest of humanity as 'a responsible global stakeholder'—a lead-in to addressing the pressing issue of Tibet. By framing his comments in such a manner, he established his right—and by extension the right of others—to disagree with both Chinese official and mainstream opinion on matters of international concern. There is a venerable Chinese expression for this position: 'A true friend,' Rudd went on, 'is one who can be a zhengyou, that is a partner who sees beyond immediate benefit to the broader and firm basis for continuing, profound and sincere friendship.' 'A strong relationship, and a true friendship,' he told the students, 'are built on the ability to engage in a direct, frank and ongoing dialogue about our fundamental interests and future vision.' The distinction was not lost on the Chinese. The official newsagency Xinhua reported: 'Eyes lit up when [Rudd] used this expression … it means friendship based on speaking the truth, speaking responsibly. It is evident that to be a zhengyou first thing one needs is the magnanimity of pluralism.' Of course, in the land of linguistic slippage it is easy to see that while for some zhengyou means speaking out of turn, for others it may simply become another way for allowing pesky foreigners to let off steam. I would like to suggest that by intervening in the political discourse of China-foreign relations in this way, Kevin Rudd was moving beyond the limitations of the 中国通 role to exploit the full potential of the broader role of sinophone. The notion of Zhōngguótōng, though acceding to the foreigner the possession of knowledge about China, still leaves him or her in effect outside of sinophone society. By contrast a sinophone like Lù Kèwén, whose status as such is signalled by his possession of a Chinese name—one known to every Chinese taxi driver—has very much become part of sinophone society. Rudd was able to use his Chinese language proficiency, and his understanding of Chinese history in which the concept of zhengyou has a venerable tradition, to assert his right as, in effect, a member of the sinophone family. As a member of that family, and one who is concerned for the well-being of its members, he was able to speak out on a sensitive issue that had serious implications for the relationship of that family with the rest of the world. Reconceptualizing the goal of learning Chinese as becoming sinophone, as developing a sinophone habitus, will allow students of Chinese to realise to the full their own potential as human beings, and their potential value to the different societies, sinophone, anglophone and other, of which they become part. Geremie Barmé sketches out this more expansive vision: Just as countless Chinese people young and old study, live and travel internationally, so do people from countries throughout the world go to study, live and travel in China. They have been lured by the economic boom and employment opportunities, by educational opportunities, or just by the desire to see what is happening in a place that has been the talk of the world. Many I have encountered have found employment in big cities, or in teaching, or in entertainment, or in a host of other professions. Indeed, it has been the fashion these last few years for Chinese firms to employ a foreigner or two who can speak Chinese to make PowerPoint presentations at meetings with new business partners, or for 'display' during negotiations, or even to play the role of a foreign 'rent-a-date' for social occasions with business people. (This is a practice familiar to many from earlier days in Hong Kong and Taiwan, or equally for those familiar with business practices in Japan or Korea.) When I speak of the creative engagement with the evolution of the Sinophone world, I do not just mean that foreigners will be a trendy accessory or a useful tool. Just as those young people of Chinese background will have an impact on world culture and that of their places of origins, so will those cosmopolites with no Chinese background who are now making the Chinese world the 'habitus' for their creativity. It is the stories of these individuals and groups that will also form part of the pluralistic 'Chinese story' that is part of the global story of humanity. And it is in its telling that the other promise of China will be realized.[34] In order to realise these goals, the restrictive, rigid, unilateral, classifications of the past need to give way to new flexible, multilateral classifications, no less in language learning than in other areas of China-foreign interactions. And just as we must recognize that the fraught history of China's relations with the rest of the world since the Opium Wars has had an impact on the conceptualisation of language learning and the cultural transformation that it enables, we must also acknowledge that such threatened anxious attempts to keep the native and the foreign apart are already giving way to much more positive mutually informed and respectful interactions across these cultural divides: it is high time for Chinese Studies to join the party. Related material from China Heritage Quarterly:

Notes:I would like to thank Jane Orton, Anne-Marie Brady and the editor of China Heritage Quarterly for their comments on an earlier version of this essay. [1] & [8] Geremie R. Barmé, 'China's Promise', The China Beat, 20 January 2010, at: http://www.thechinabeat.org/?p=1374 [2] & [12] Edward McDonald, Learning Chinese, Turning Chinese: challenges to becoming sinophone in a globalised world, London: Routledge, 2011. [3] Haun Saussy, Great Walls of Discourse and Other Adventures in Cultural China, Harvard East Asian Monographs 212, Cambridge MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2001. [4] Geremie R. Barmé, 'On New Sinology', Chinese Studies Association of Australia Newsletter, No.3, May 2005. Also online at: http://rspas.anu.edu.au/pah/chinaheritageproject/newsinology/index.php [5] Shu-mei Shih, 'Sinophone Articulations Across the Pacific' Ostasiatisches Seminar: Chinese Diasporic and Exile Experience, Universität Zürich, 10-14 August 2005. [6] Shu-mei Shih, Visuality and Identity: Sinophone Articulations across the Pacific, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007. [7] Sheldon Hsiao-peng Lu, 'Review of Shih Shu-mei's Visuality and Identity: Sinophone Articulations across the Pacific', in Modern Chinese Literature and Culture published in 2007, at: http://mclc.osu.edu/rc/pubs/reviews/lu.htm [9] Song Qiang, Zhang Zangzang and Qiao Bian, Zhōngguó kĕyĭ shuō 'bù' [China can say 'no'], Beijing: Chinese Industrial and Commercial Joint Press, 1996. [10] Edward McDonald 'Getting over the Walls of Discourse: "Character Fetishization" in Chinese Studies', Journal of Asian Studies, 68.4 (2009): 1189-1213. [11] Geremie R. Barmé & Linda Jaivin, eds, New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese Rebel Voices, New York: Times Books, 1992. For a more recent comment by Barmé on guoqing and its abiding role, see his 'Strangers at Home', Wall Street Journal, 17 July 2010, online at: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704682604575369390660095122.html?mod=WSJ_LifeStyle_LeadStoryNA [13] William A. Callahan, China: The Pessoptimist Nation, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. [14] B. Adamson, 'Barbarian as a foreign language: English in China's Schools', World Englishes, 21(2) (2002): 257-267. [15] Y.Y. Liu, 'Chinese Attitudes Towards English', in K. Parry & X.J. Su, eds, Culture, Literacy, and Learning English: Voices from the Chinese Classroom, Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 1998, pp.106-108. [16], [21] & [25] Anthony Giddens, Modernity and Self-identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1991. [17] & [18] S.Y. Teng and J.K. Fairbank, China's Response to the West—A Documentary Survey 1839-1923, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1954. [19], [20], [24] & [29] Orton, Jane 'English and the Chinese Quest', in Joseph Lo Bianco, Jane Orton & Gao Yihong, eds, China and English: Globalisation and the Dilemmas of Identity, Bristol: Multilingual Matters, 2009, pp.79-97. [22] Lu Jianming 'Jìnyíbù yĭ kēxué tàidù duìdài hànyǔ jiàocái biānxiĕ' (Taking a more scientific attitude towards the writing of Chinese teaching materials), in Selected papers from the 9th Conference on International Chinese Teaching, Beijing: Higher Education Press, 2010. [23] Janet Zhiqun Xing, Teaching and Learning Chinese as a Foreign Language: A Pedagogical Grammar, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2006, p.15. [26] Anne-Marie Brady, Friend of China: The Myth of Rewi Alley, London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003. [27] Anne-Marie Brady, Making the Foreign Serve China: Managing Foreigners in the People's Republic, Lanham MA: Rowan & Littlefield, 2003. [28] Gao Yihong 'Sociocultural Contexts and English in China: Retaining and Reforming the Cultural Habitus' in Joseph Lo Bianco, Jane Orton & Gao Yihong, eds, China and English: Globalisation and the Dilemmas of Identity, Bristol: Multilingual Matters, 2009, pp.56-78. [30] R. Wilson, S. Greenblatt & A. Auerbacher Wilson, eds, Moral Behaviour in Chinese Society, New York, N.Y.: Praeger, 1981. [31] Gao Yihong, 'Developing Intercultural Communicative Competence: Going Across and Going Beyond,' Foreign Languages and Their Teaching, 27.10, 2002. [32] Jean Brick, China: a handbook in intercultural communication, 2nd ed., Sydney: National Centre for English Language Teaching and Research, Macquarie University, 2004. [33] Geremie R. Barmé, 'Rudd Rewrites the Rules of Engagement', Sydney Morning Herald, 12 April 2008, online at: http://www.smh.com.au/news/opinion/rudd-rewrites-the-rules-of-engagement/2008/04/11/1207856825767.html [34] Geremie R. Barmé, 'Worrying China and New Sinology', China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 14 (June 2008), at: http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/articles.php?searchterm=014_worryingChina.inc&issue=014 |