|

|||||||||

|

ARTICLESRECONCILING TOURISM AND CONSERVATION: THE CASE OF HISTORIC TOWNS Illustration 1: Dafu House, built in 1674, in Xidi village, Anhui province.

Illustration 1: Dafu House, built in 1674, in Xidi village, Anhui province.

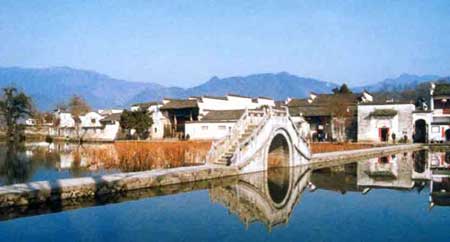

China has a far greater number of inhabited ancient and historic urban areas, towns, villages and hamlets than UNESCO could ever hope to list for protection. Visual-spatial ties of long-standing and harmonious architectural dominants translate into tourist appeal and economic potential, but abrupt shifts in economic and urban planning over the past fifty years have broken many of these ties. The switch in the 1950s to a notion of urban planning which insisted that a modern Chinese city should be an industrialised city without walls constructed around a centralizing concept such as a open space enclosing a monument was directly antithetical to the traditional Chinese notion of a city as a walled space with discrete residential districts around markets and public spaces afforded by temples. Such economic and urban planning also required that workers' residences were adjacent to industrial work spaces. Heritage management and heritage urban planning, now taken for granted in many parts of the world, were not seen to be part of Chinese urban planning, and even when tourism became a major component in Chinese economic and urban planning from the 1970s and the 1980s, heritage management was not considered relevant. The notion of cultural heritage was still reserved for isolated structures and monuments, not urban landscapes. As a result the inherited visual-spatial ties in Chinese cities were under constant threat; many historic spaces in cities passed crisis point, and some simply ceased to exist with no original architectural integrity intact. Few Chinese urban landscapes have undergone such dramatic destruction of their traditional architectural integrity, and their living and cultural environments, as Shaoxing in Zhejiang province. The problem here can be fully attributed to the lack of long-term environmental planning and a failure to anticipate and plan for the needs of future tourism. In the mid 1980s large sections of Shaoxing still evoked the descriptions of that city to be found in essays by the city's best known writers, Lu Xun (d.1936) and his brother Zhou Zuoren (d.1967), but now it is hard to imagine that Shaoxing was only recently a typical water-girt traditional Zhejiang township. In 1986 it was still possible to travel by local sampan from the Temple of Yu to the near centre of town via East Lake. The canals were relatively clear, the vistas charming, and litter only moderately intrusive. By the late 1990s the canals were impassable in places because of weed and garbage, the water was toxic, and the vistas often dominated by freeway structures, looming housing projects and mass entertainment fairgrounds replete with replica French chateaux and a faux Taj Mahal. The delights of the traveller are, of course, irrelevant to a town's inhabitants and the palpable losses in perceived lifestyle are perhaps more striking to the outsider. Many a visual paradise might come with the proviso: But would you really like to have to live there?  Illustration 2: Nanhu (South Lake) in Hongcun village, Anhui

Illustration 2: Nanhu (South Lake) in Hongcun village, Anhui

Poverty has often proved to be the most potent conservationist, in the same measure as unfettered economic development presents the greatest peril to the health and equilibrium of a more traditional urban environment. This is a paradox for conservationists throughout the developing world, and most of rural China remains part of the Third World, even if it is comparatively impressive in overall infrastructural terms. It is only over the last decade that heritage planning has become a concept in urban environmental planning in China. Many factors account for the shift in perception: the rise of a new generation of architects attuned to international practices; an awareness of the problems posed by industrial pollution; the growth of a generation of aspiring home owners who pay attention to local real estate values; and the advent of the eco-conscious tourist [1] who now sets the pace for tourism in China through lifestyle publicity in the media. The appeal of ancient towns has been nurtured among tourist consumers in China, and many ancient towns and villages now clamour for a heritage listing, egged on by the promise of tourist income. Tourism, however, provides both weal and bane for conservationists. Obviously, a sharp peak in tourism creates more problems for heritage urban management, at the same time as it provides the income and motivation to undertake conservation work. Heritage tourism as a functioning economic mode perhaps requires more planning and investment than the earlier notion of fixed facility tourism that was dominant in China until several years ago. In the latter model of tourism, entry fees and a high concentration of spending outlets ensure a quick return on investments. Heritage urban planning that both satisfies the needs of residents and caters to heritage tourism requires carefully defining the parameters of that planning by defining what actually constitutes a city, town or village. This fundamental task is more difficult than it might first appear. As in English the terms "city", "town" and "village" exist both as administrative entities and as mere figures of speech. The ancient Chinese word cheng, which is often translated into English as "city", literally identifies an urban entity by the existence of enclosing walls, and this principle still holds in modern Chinese usage. Similarly the word shi, used today for a "municipality" or "city" originally indicated a market. The picture is further complicated by the use of other traditional and modern terms to denote urban administrative units, such as "—qu" (district), "—zhou" (prefecture), and "—fu" (large prefecture). Moreover, "villages" and "towns" can exist within cities, as can districts. However, some Chinese large towns to which the suffix "-shi" (municipality or city) has been affixed can be smaller than either a "-xian" (county) or a "-zhou" (prefecture). Defining an urban unit for the purposes of heritage tourism, which has a visual-spatial homogeneity and uniqueness deemed to be worthy of preservation is even more complex. The space can be a section of a city encompassing merely one street or a number of streets, or extend to include an entire suburb or district. Being party to a number of UNESCO agreements in which the concept of heritage urban planning is implicit, China, ironically, applied for and obtained UNESCO inscription of three ancient towns as World Heritage Properties before the State Administration of Cultural Heritage (SACH) and the Ministry of Construction sat down together in 2003 to determine the guidelines for defining an ancient town and ancient village for Chinese heritage planning purposes and selecting a preliminary list of historic towns and villages. The UNESCO inscriptions are of course tentative, and wisely heed the tourism facilities and needs of listed sites.  Illustration 3: Street scene facing market tower in the ancient town of Pingyao, Shanxi

Illustration 3: Street scene facing market tower in the ancient town of Pingyao, Shanxi

The three listed towns - Pingyao in Shanxi province (listed in 1997), the old town of Lijiang in Yunnan province (1997; see "Litigation Surrounding Nakhi Ancient Music" in this issue) and the ancient villages of Xidi (see Illustration 1) and Hongcun in southern Anhui (2000)(see Illustration 2) - have benefited economically from the listing, but have suffered increased threats to and destruction of urban heritage largely as a result of excessive privatisation. The streets and shops along the main street of Pingyao maintain the overall look of a prosperous 17th-19th century northern Chinese walled town, and there are several well restored and maintained large family compounds in the vicinity of the city. Although the city's overall layout of streets and surrounding wall date from the time of its expansion in the 3rd year of the Hongwu reign of the Ming dynasty (1370), Pingyao owed its prosperity to the ascendancy of the Shanxi merchants in the Ming and Qing dynasties. To obviate the need to transport large sums of cash being handled by these merchants under escort, a new form of financial institution emerged in Pingyao. Called in Chinese the piaohao, the first of a kind of modern draft bank, the Rishengchang Piaohao, was established in the town in 1824 and, over the following century, more than 50 other piaohao institutions were founded throughout the empire, 20 of which had their headquarters in Pingyao. Pingyao is a functional modern town and part of its charm for tourists derives from its vibrant street life framed by an elegant sufficiency in the centre of the town of ancient architecture, (see Illustration 3) although most has been modified. There are very few buildings in the town preserved with utter verisimilitude, a seemingly unattainable ideal in a living commercial environment. The walls, scaled by most visitors who want an overview of the large town, have suffered much wear and tear, and collapses of sections are frequent. The most recent collapse near the town's southern gate occurred on 17 October 2004. A preliminary investigation by the Pingyao Cultural Heritage Administration resulted in the claim that the collapse was a result of structural defects in the wall itself, because the 630-year Ming walls were built on top of exisitng structures. However, Margaret Wilson, familiar with the problems faced by "conservationists" in Pingyao, points out that "none of the explanations for the collapse of the south gate mention that about three metres of earth were excavated from a long section of the south wall, revealing its original base. Also, although the wall is described as being six to eight metres thick at the base, the barbican gates have caves dug into them and a wall with a four or five metres deep cave is no longer six to eight metres thick! The collapse revealed openings into three of these caves The restoration of the collapsed section was completed on 1 May 2005, just in time for the inundation of May Day holiday tourists. However, each renovation of the walls seems to remove more of the authenticity of the original. Lijiang (see Illustration 4) in Yunnan has also suffered as a result of the growth of tourism. This is despite the fact that UNESCO has paid great attention to the issue of culture heritage management in Lijiang and set up a training group for local planners. The excellent case study report on heritage protection and tourist development in the ancient town of Lijiang submitted in 2000 speaks of "models of co-operation among stakeholders", but its findings are alarming in places. Although the listing of Lijiang was intended to preserve the old town, the influx of tourists has meant that most residents have moved out of their homes and the houses have been turned into shops, restaurants and inns. The research report written under the aegis of the vice-governor of Dayan Town, Duan Songting, describes this as serious "spatial pollution". The report describes the economic pollution, raw material cultural pollution and audio-visual pollution (including street furniture) as not serious, but laments the increase in "spiritual pollution" and the vast quantities of rubbish and garbage created by the large influx of tourists. The case study includes the results of a random community survey of 220 residents in Dayan Town, and the results reveal that the community is well aware of the need for tourism and the dilemmas it creates. Although the full report can be found online as a PDF file and downloaded, several responses from the survey are worth quoting here. Of those surveyed 45.7% of people with jobs work in tourism, and so it is not surprising that when asked whether they hoped that tourist numbers increase, 172 people expressed the wish that the number of tourists coming to Lijiang would continue to increase, while 43 hoped that the number remained stable. Moreover, when asked about the impact of tourism, 106 stated that tourists had no effect on the town, 36 believed that tourists had a positive effect, and 67 said that tourists had both positive and negative effects. Asked whether they are pleased with tourism development, 90 people said that they were satisfied, while 113 answered that they believed that tourism in Lijiang has both positive and negative impacts. Heartening for future development of the town are the responses to questions related to heritage management. Of those surveyed, 171 believed that the old town was the main reason foreign and domestic tourists came to Lijiang, while only 34 were unsure. Moreover, 179 believed that the government should invest more in protecting the old town, while only 16 stated that they thought it was unnecessary, and 20 were unsure.  Illustration 4: Canal and houses in the ancient town of Lijiang, Yunnan

Illustration 4: Canal and houses in the ancient town of Lijiang, Yunnan

All three of UNESCO's ancient village and town listings were largely based on evaluations of vernacular architectural heritage. Chinese planners are developing their own guidelines on vernacular architecture to conform to international charters, as well as recommendations regarding the conservation of historic towns and villages. The most important of these is the International Council on Monuments and Sites' Charter for the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas adopted in 1987, better known as the Washington Charter. Although the concept of "historical cultural protected areas" (lishi wenhua baohuqu) first appeared in cultural heritage documents in 1985, it was some time before the concept of cultural protection was extended from monolithic and isolated architectural entities to inhabited environments. It was not until 2002 that The Cultural Relics Protection Law of the PRC (Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo Wenwu Baohu Fa) included the concept of extending State Council protection to "towns, streets and villages deemed by provincial, regional and municipal authorities to have major historical value or revolutionary commemorative significance". In 2003 the Ministry of Construction and the State Administration of Cultural Heritage (SACH) collaborated on compiling China's first listing of historic towns and villages (Diyi pi Zhongguo lishi wenhua mingzhen/cun]), which was issued in October of that year. This was the first step in establishing a national system for protecting endangered historic towns and villages. The list comprised 10 towns and 12 villages, and all were from ethnic Han areas. Two villages listed by UNESCO, Xidi and Hongcun both in Anhui, are included in the list of villages. Here towns and villages are presented in separate tables, even though no clear criteria for the distinction between the two groups are provided by SACH: Table of Famous Historic Cultural Towns[Listed historic cultural towns appear in the left column, with the administrative division(s) above them appearing in the second column from the left and the province appearing in the central column.]

Particular regional cultural systems were identified and particular regional cultures were prioritised in the selection. Shanxi province, for example, which can be roughly equated with an identifiable San Jin (Three Jin) cultural system, is rich in towns and villages that exemplify this culture. However, only one town and one village from Shanxi were selected. Pingyao, which was selected by UNESCO in 1997 for listing as an ancient city, is in some ways not typical of the San Jin town or village. Shaanxi, and especially northern Shaanxi, arguably has more unique and homogeneous ancient towns than Shanxi, yet only one village from Shaanxi was selected. The cultural regional system to which that village belonged was described as Qin-Long culture, a regional type that is found in both Gansu, Shaanxi and even in some parts of Qinghai adjacent to Gansu. No towns or villages were selected from Gansu, Qinghai, Yunnan, Guangxi, Hainan, Hubei, Hunan, Henan, Hebei or anywhere in the north-east. Moreover, no town or village in Tibet, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia or Xinjiang was selected. The list is dominated by villages and towns in Jiangsu and Zhejiang, classified as belonging to the Wu-Yue cultural region system. This is surprising because it would seem that one of the criteria for a first listing should be the breadth of what is termed "typicality", signalling the range of future choices. "Architectural heritage" (jianzhu yichan xing) is also cited as the main criterion or "value/characteristic-type" (jiazhi tese leixing) cited for selecting particular towns or villages for inclusion on the first list. Put simply, the choices seem to be dictated by the "picturesque" nature of these particular towns, rather than the homogeneity of their architectural traditions or the typicality or representative status they have within different regional vernacular architectural systems. Habitation and sustainable economies were also not necessarily criteria for inclusion on the list. For example, Chuandixia (often pronounced Cuandixia), an atypical stone mountain village in the Mentougou district of western Beijing is not, or rather was not, inhabited when the list was compiled. It is now a resort with a floating population of artists and artisans who come from Beijing for short periods. The village was essentially abandoned ten years previously and was mostly used as a film set. Its preservation has come about in part because the inhabitants were active partisans in the anti-Japanese war affiliated with the Communist armies. It is certainly picturesque and deserving of preservation, but it is by no means a "living" village, not does it make much sense to describe it as representative of the Zhao-Yan cultural system in so far as that term refers to architectural heritage in the region. Only one village on the list has its "value/characteristic-type" (jiazhi tese leixing) described as "ethnic uniqueness" (minzu tese leixing). This is Tianluokeng in Fujian, a Hakka village. "Ethnicity" does not refer to a non-Han Chinese ethnic group, and the cultural regional system is typified as Min-Tai (Fujian-Taiwan). Tianluokeng is in fact also architecturally quite distinctive because the village consists of large round collective fortress compounds. Table of Famous Historic Cultural Villages[Listed historic cultural villages appear in the left column, with the administrative division(s) above them appearing in the second column from the left and the province appearing in the central column.]

Assessing this listing, three scholars engaged in urban resources and tourism studies point out that strategies need to be developed to conserve historic cultural towns and villages that are different from those adopted for cities.[2] Conservationist working on towns and villages need to be alert to the need for the restoration, maintenance and revitalization of vernacular architecture, as well as to sense of place (the streetscape, village shape, rural environment, rustic culture, neighbourhood and behaviour landscape). The natural and rural uniqueness of ancient villages and towns also requires attention to broader environmental protection issues. These scholars conclude that town planners, architects, economists, sociologists, historians, geographers, environmentalists, landscape ecologists and other hands-on specialists must be engaged in interdisciplinary efforts to develop criteria that will maintain local heritage sites both for the residents and the tourists. [BGD] REFERENCES[1] A number of publishing houses have now issued guidebooks to aid "the vernacular traveller" in search of authentic village life lost in urban China. Taking their cue from the media, young Chinese are seeking out the local version of "The Lonely Planet experience". China's ethnic minority regions, wilderness destinations and ancient historic towns and villages have inversely become sought after destinations. Popular series of attractive "alternative" guidebooks produced in 2005 are Zhongguo guzhen you (China ancient village travel), published by Shaanxi Normal University Press, and Guzhen shu (Ancient village books), published by Nanhai Chuban Gongsi. At the time of writing, each series comprises nearly 30 separate volumes. Details of these guidebooks can be found at: www.readroad.com [2] Zhao Yong, Zhang Jie and Zhang Jinghe, "Woguo lishi wenhua cunzhen baohu de neirong yu fangfa yanjiu" (Research on the content and methodology for conserving historic cultural towns and villages in China), Renwen dili (Human Geography), 2005:1, pp 68-74. All three scholars are attached to the Department of Urban and Resources Science, Nanjing University. In addition, Zhao Yong is also affiliated to the Construction Department of Hebei Province, while Zhang Jinghe is affiliated with the College of Earth Resources and Tourism at Anhui Normal University. |