|

|||||||||

|

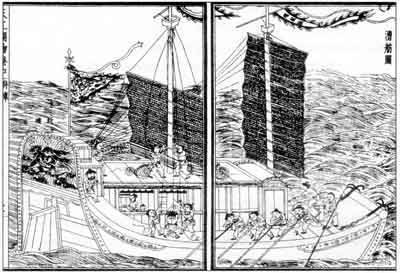

ARTICLESSHIPPING NEWS: ZHENG HE'S SEXCENTENARYThe recent production of a set of 600 Ming-style imperial cooking vessels, ironically including a steamboat, to celebrate the 600th anniversary of the maiden voyage of the 15th century navigator Zheng He, better known by the arresting honorary title of the Three Treasure Eunuch (Sanbao taijian), is perhaps no more an ironic juxtaposition of the ancient and the modern than the recent carving on Qin-style bamboo slips of China's Anti-Secession Law aimed against Taiwanese independence and approved by the National People's Congress on 13 March 2005.[1] The role of cooking in China's "march on the world" and the evocation of Qin Shihuang's legal codes in the interests of national unity reveal the breadth of China's contemporary appeal to history encompassing the range of cultural production from gustatory delights and national treasures all the way to kitchen kitsch.  Illustration of flat-bottomed caofang or coastal tributary grain vessel from woodblock

edition of the technological and scientific treatise Tiangong kaiwu (Exploitation of the Works of Heaven), 1637 [as reproduced in Gujin tushu jicheng]

Illustration of flat-bottomed caofang or coastal tributary grain vessel from woodblock

edition of the technological and scientific treatise Tiangong kaiwu (Exploitation of the Works of Heaven), 1637 [as reproduced in Gujin tushu jicheng]

The ancient-style cooking vessels, each weighing approximately 30 kilograms, and emblazoned with appropriate relief-carved dragon motifs and a schedule of Zheng He's seven voyages spanning the 28-year period from 1405 to 1433, went on display in the Nanjing Museum on 19 May 2005. The vessels took six months to produce, and absorbed the creative energies of six local artists. This tribute to Zheng He, master mariner of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), is merely one frisson in the flurry of activities organised for the sexcentenary. Stamped with patriotism, most events are designed to appeal to Chinese who hail from the various hometowns and localities in China associated with Zheng He, or who now live in the areas of Southeast and South Asia, as well as the Middle East and even East Africa, once visited by Zheng He's fleets. Although Zheng He came to be deified and included in local Chinese pantheons in Tian Hou temples, he was in fact a Muslim, a fact not overlooked in the present celebrations.[2] Zheng He (1371-1433), commander-in-chief of the renowned Ming expeditionary fleets of the early 15th century, was born into a Muslim family surnamed Ma in Kunyang, Yunnan province. His grandfather and father both bore the title Hajji, suggesting that they had made the pilgrimage to Mecca. As a boy of ten, Zheng He was recruited for military service as a eunuch in the retinue of Zhu Di, Prince Yan, who usurped the throne in 1402 to become known to history as the Yongle Emperor, known posthumously as Emperor Ming Chengzu (see illustration). For his service in helping the new emperor win the throne after three years of vicious warfare, Zheng He was promoted in 1404 to the position of Director of Eunuch Affairs and given the surname Zheng.  Detail of portrait of the third Ming emperor, Zhu Di, better known as the Yongle Emperor

[Original work is in the collection of the China National Museum]

Detail of portrait of the third Ming emperor, Zhu Di, better known as the Yongle Emperor

[Original work is in the collection of the China National Museum]

The overthrown emperor, Zhu Yunwen, was never captured nor was his body found, and was rumoured to have fled abroad. Some accounts state that the Yongle Emperor was so obsessed with the desire to find his potential rival and remove the possibility of the throne ever reverting to him or his descendants that he conceived the plan to despatch an expeditionary fleet to hunt to the ends of the earth for the potential pretender. This explanation seems far-fetched, although it should be viewed in the context of the brutal dictatorship characterised by fratricidal enmity that was instituted by the founder of the Ming dynasty, Zhu Yuanzhang. Even if the Yongle Emperor was obsessed with maintaining his own power, the voyages seem to have been also conceived as part of a diplomatic and commercial initiative undertaken because the Chinese were hemmed in by the Mongols on the north and north-western frontiers. Emperor Ming Chengzu ordered all coastal shipyards to construct vessels to be part of his first fleet. However, according to Professor Xin Yuan'ou of Shanghai's Jiaotong University, although many shipyards were involved in assembling the pan-shaped hulks of the vessels, similar to shallow draught rice transportation vessels (caofang, see illustration), the Longjiang Shipyard in the southern Ming capital Nanjing had mastered the technology for modifying such hulls so that they were wedge-shaped like Western vessels. Hulls produced in other shipyards were transported to Nanjing for finishing. How this "Western" technology was introduced to China is not explained in the press report by Professor Xin. By 1405, some 1,180 ships of various types had been built, according to Chang Kuei-sheng's account (see references), and Zheng He was appointed to direct the expeditions. The first voyage began in the winter of 1405 with a fleet comprising more than 60 large vessels and 255 smaller vessels. The total crew consisted of more than 27,800 men. The valuable cargoes carried by the vessels and the range of participating vessels in the flotilla demonstrate that the reasons for the voyages were more complex than the mere hunt for a pretender. The first fleet sailed from the Yangtze estuary and headed south, travelling along the coast to Champa, a wealthy kingdom on the Indochinese coast, and then to Thailand. Passing through the Straits of Malacca, the flotilla was attacked by an armada led by a powerful Chinese pirate, Chen Zuyi, who controlled these waters and the kingdom of Palembang in Sumatra. Zheng He's forces succeeded in defeating Chen, although Zheng lost five thousand of his men. After recuperating in Palembang, Zheng He entered the Indian Ocean and sailed on to India and Sri Lanka. He returned to China in 1407 with his captive Chen, who was to be executed. This first voyage, effectively resulted in wresting control of the Straits of Malacca, the installation of a ruler friendly to China in Palembang, and the re-opening of a sea route for Chinese vessels to the Indian Ocean. Although the sea route between the Persian Gulf and China was known in the Tang and Song, and possibly even as early as the Han dynasty, trade along this route was conducted mostly by private merchants. Six subsequent voyages took Zheng He to increasingly distant destinations, as can be seen in the following table:

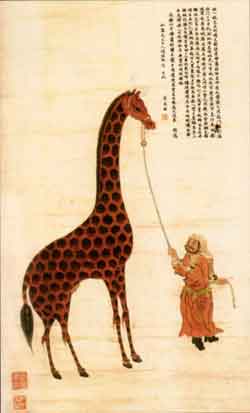

Zheng He's voyages should have been the prelude to a dramatic new chapter in Chinese maritime trade and commercial expansion, given their potential to establish or consolidate a desire for Chinese luxury goods such as silks and ceramics in Southeast Asia, South Asia and the Middle East. During his voyages Zheng He collected "tribute" items from various states that included spices and aromatics, coral, glass, sandalwood and other exotic timbers, as well as exotic species of birds and animals, including even a giraffe (see illustration).  Bronze bell cast by Zheng He

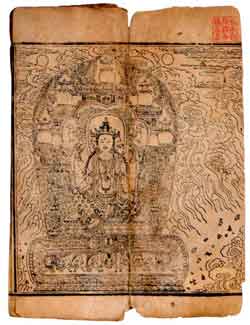

Bronze bell cast by Zheng HeOverall height: 83 cm Width at opening: 49 cm Collection of the China National Museum [Bell originally cast in Fujian in 1431 on eve of his 7th voyage] However, the voyages were not the prelude to an era of commercial maritime expansion for the Chinese empire. Tribute horded in the palace did not lead to a boom in trade. Extravagant ocean expeditions were discontinued by the successor of the Yongle Emperor, Zhu Gaochi (reign title Hongxi), better known by his posthumous title of Emperor Renzong, even though he only ruled for one year from 1424 to 1425. Zheng He would undertake a subsequent seventh voyage, but the weight of opinion at court eventually led to the condemnation of state-sponsored expeditions as vainglorious. Maritime trade itself was also banned for long periods, its conduct reverting to private entrepreneurs and outright privateers. The most extravagant claims for Zheng He have been made not in China, but in Great Britain. In 2002 Gavin Menzies, a retired Royal Navy submarine commander, made public his contention that Zheng He had sailed to the Americas, 72 years before Christopher Columbus. More surprising is Menzies' claim that Zheng He did not sail to the Americas from the west, but rather from the east, thereby having completed a near circumnavigation of the earth. To support his arguments, Menzies claims that he has located wrecks of Zheng He's voyage of 1421 in the Caribbean, although does not intend revealing their location until he has documented his finds. Few Chinese scholars accept Gavin Menzies' claim that Zheng He discovered the Americas and completed the first circumnavigation of the planet,[3] but the success of Menzies' 1421: The Year China Discovered the World demonstrates that Zheng He exercises an appeal far beyond China. Internationally, one group of enthusiasts is following the trajectories of Zheng He's voyages. The Taiwan-based Society of Extreme Exploration, directed by Alan Hsu, has invested US$5 million in a state-of-the-art sailing voyage to visit all Zheng He's ports of call. The team, comprising explorers and historians, plans to complete the trip between July 2005 and June 2008. Chinese communities in Singapore, Taiwan, the Philippines and Indonesia are also celebrating Zheng He's sexcentenary. Chinese businessmen in Semarang, Indonesia, announced in May 2005 that they are investing in a commemorative seminar and photographic exhibition, as well building a new Zheng He Temple in the city. Semarang is already known for its Sam Poo Kong Temple, where Zheng He is said to have spent time in meditation during a visit there with his fleet. Zheng He has associations with several other places in Indonesia. Legend has it that Zheng He and members of his fleet taught the residents of the Indonesian city of Yogyat how to dig water wells, and in Bali many people worship a deity called Igusti Ngurah Subandar, the local title for the treasury minister who travelled with Zheng He. Many ethnic Chinese and Balinese pilgrims worship at the minister's temple on Kintamani Mountain, two hours drive from Denpasar. In Surabaya, the capital city of East Java Province, a mosque named after Zheng He has also contributed to local religious and cultural life since it was established two years ago.  Buddhist sutra the printing of which was commissioned by Zheng He in the 1st year of the reign of the Yongle Emperor

[Collection of the National Library of China, Beijing]

Buddhist sutra the printing of which was commissioned by Zheng He in the 1st year of the reign of the Yongle Emperor

[Collection of the National Library of China, Beijing]

A number of new works on Zheng He are being published. These include an album of several hundred photographs of locations and sites scattered through China and Southeast Asia associated with Zheng He, co-published in June 2005 by Yunnan Chenguang Publishing House, Yunnan Art Publishing House and Yunnan People's Publishing House. Of particular interest to scholars is the publication of a reproduction of the original genealogy of Zheng He's family. Although Zheng He was a eunuch, some 250 Muslims, now scattered in Yunnan and Jiangsu provinces, as well as in the Chiang Mai area of northern Thailand, claim to be his descendants. As was customary, Zheng adopted the son of his elder brother. After completing his third voyage, Zheng He returned as a hero and high-ranking official to his birthplace Kunyang, where he not only had a tomb constructed for his father, but also adopted a son of his elder brother and began the record of his family genealogy. On its first page is the tomb epitaph for Zheng He's father, as well as details of his voyages and his contribution to the construction of a mosque in Nanjing. The genealogy was maintained by his descendants for four centuries down to the late 19th century. In 1937, Li Shihou, a historian, had the hand-written document photographed, before arranging for its return to the Zheng family. Li later made copies of the genealogy from his prints, but the work has been largely unavailable to historians. Its present reproduction is therefore timely. In China, conferences, exhibitions and seminars are being organised for maritime buffs, cartography enthusiasts, historical geographers and general historians. A number of conferences on aspects of Zheng He have, in fact, been held since last year. In both December 2004 and in May 2005, Fuzhou in Fujian province was the venue for a sexcentennial seminar and conference, organised under the auspices of the Ministry of Communications. The Chinese government has set up a special office headed by that ministry to organize activities to mark Zheng He's contribution to the history of navigation, and seminars and exhibitions have already been staged in Shanghai, Beijing, Dalian, Qingdao, Quanzhou, Changle and other places. The Fuzhou forum in May this year was a five-day long event attended by more than 300 domestic and overseas scholars. The organisers stated that the forum was designed to publicize Zheng's contributions to the world navigation industry and to all mankind, and to promote cooperation and exchange between China and other countries by perpetuating "Zheng's spirit of loving peace, bravery and diligence".  Modern statue of Zheng He in Changle, Fujian

Modern statue of Zheng He in Changle, Fujian

A conglomerate drawing together of China's shipping and shipbuilding industries has even convened a twinned exposition in Shanghai (8-14 July 2005) designated the Zheng He Ocean Voyages Exhibition and International Marine Expo that includes among its organizers the Ministry of Communications, the Commission of Science Technology and Industry for National Defence of the PRC, the State Oceanic Administration of the PRC and the Shanghai Municipal People's Government, to name only the major participants. A less confrontational exhibition commemorating Zheng He's voyages is currently being curated at the Chinese National Museum in Beijing. The exhibition is scheduled to open in September 2005, and a major catalogue is being prepared for it at China Social Sciences Publishing House.  Qing dynasty copy by Chen Zhang of a Ming dynasty silk scroll painting by Shen Du titled Banggela jin qilin tu (Tribute giraffe from Bengal)

[Collection of the China National Museum]

Qing dynasty copy by Chen Zhang of a Ming dynasty silk scroll painting by Shen Du titled Banggela jin qilin tu (Tribute giraffe from Bengal)

[Collection of the China National Museum]

There is an extensive literature in English and Western languages on Zheng He's voyages and China's maritime trade in general, with major contributions made by Paul Pelliot, J. J. L. Duyvendak, Wang Gungwu, J. V. G. Mills, and Roderich Ptak. [4] In China scholarship on Zheng He parallels the growth of the "New History" established by Liang Qichao (1873-1929) at the beginning of the 20th century. In 1904, in his journal produced in exile in Yokohama Xinmin congbao (New people's miscellany), Liang Qichao published a seminal article entitled "Zuguo da hanghaijia Zheng He zhuan" (Biography of Zheng He, master mariner of the fatherland). Liang Qichao pressed Zheng He into the service of a resurgent patriotism typified by concern for China's humiliated international position at the end of the 19th century. For Liang Qichao, Zheng He's achievements provided a model for what Chinese could achieve. Later Chinese scholarship was also concerned with placing Zheng He's maritime achievements within a world historical context. In 1929 Xiang Da, writing under the pen-name Jueming, published an article titled "Guanyu Sanbao Taijian xia Xiyang de jizhong ziliao" (Several documents concerning the voyages of the Three Treasure Eunuch to the West). This was the first attempt by a Chinese scholar to draw together the Chinese sources documenting Zheng He's voyages. This documentation includes the various inscriptions at his grave and other sites associated with him across China. The leading historians of the 1930s who examined Zheng He's life and career were Feng Chengjun, who worked with Paul Pelliot, Wu Han and Tong Shuye. Pioneering studies by other scholars on texts related to Zheng He include: Zheng Hesheng's "Loudong Liujiaxiang Tianfei-gong shike 'Tong Fan shiji ji'" (The carved text of Records of Foreign Relations in the Tianfei Temple in Liujiaxiang, Loudong) published in Guofeng, 1935; Xia Guangnan's "Zheng He Taigong muzhi mingba" (The text and colophon of the tomb epitaph of Zheng He Taigong) in Yuandai Yunnan shidi luncong (Articles on the history and geography of Yuan dynasty Yunnan), Zhonghua Shuju, 1935; and Sa Shiwu's "Kaozheng Zheng He xia Xiyang niansui zhi you yi shiliao: Changle 'Tian Fei lingying bei' tapian" (The study of a further historical document regarding the dates of Zheng He's voyages: A rubbing of the stele Tian Fei lingying bei from Changle), Tianjin: Dagong Bao: Shidi zhoukan, 1936). In the 1930s and 1940s, a group of scholars, exemplified by Feng Chengjun, focussed on the significance of Zheng He's voyages for Chinese trading and diplomatic relations in South-east Asia, while another group examined the significance of the voyages for what they revealed about Ming court politics. Whatever the approach, the uppermost concern has been determining the nature of the voyages, and comparisons were made with the voyages of da Gama, Magellan, Columbus and Cook. The general consensus has been that Zheng He's enterprise was not an imperial undertaking aimed to establish colonies, in contrast with most European voyages. The fact that Zheng He's flotillas were manned by such large numbers of soldiers is generally overlooked by both foreign and Chinese scholars. [5]  Grave of Zheng He at the foot of Niushoushan mountain, Nanjing

Grave of Zheng He at the foot of Niushoushan mountain, Nanjing

From the 1940s down to the present, there has been much debate regarding the dimensions of Zheng He's "treasure ships" (baochuan). As recorded in Ming shi and other ancient Chinese texts, these "treasure ships" were massive, dramatically larger than ships made anywhere else in the world at that time. In 1947 Guan Jincheng in his "Zheng He xia Xiyang de chuan", published in Dongfang zazhi in 1949, questioned the dimensions in Ming shi and sought to scale them down, citing for authority more modest figures recorded in a stele in Jinghai Temple discovered by the scholar Zheng Hesheng. Guan Jincheng effectively argued that the baochuan of Zheng He were shachuan or flat-bottomed estuarine craft. In the 1950s, however, the Ming shi account was lent credence by archaeological discoveries. A massive ship's tiller was discovered by archaeologists in 1957 at the site of the Ming dynasty Longjiang shipyard in Nanjing that produced the "treasure ships". Assimilating this new data, Zhou Shide published an article in 1962 (see references) asserting that the dimensions provided in Ming shi were basically correct, and in 1985 Xi Longfei and He Guowei confirmed in a paper that ancient vessels unearthed in the ports of Quanzhou and Ningbo also demonstrate that the dimensions provided in Ming shi were sound. Han Zhenhua argued that a large baochuan was approximately 150 m in length at the waterline and 60 m in width and depth; a small baochuan was less than half that size. From the 1970s onwards scholarship on Zheng He has accrued at a steady pace around the world, with major contributions made by Luo Rongqu, Tian Rukang, Jin Qiupeng and many others (see references, below). Scholars have focused on the routes Zheng He travelled, using evidence reinforced by closer examination of Ming dynasty nautical charts and discoveries of Chinese ceramics along the east African coast and the littoral of southern and south-eastern Asia. The sexcentenary has also provided the incentive for further research and a number of new and recent discoveries have been publicised. In July 2004 Xinhua News Agency reported that China's earliest temple dedicated to Zheng He was discovered in Hongjian village on the northern coast outside Xiamen in Fujian province, even though the discovery of this temple dating from the early Qing dynasty was made by a researcher from Xiamen University in 1989. Statues of Zheng He and his assistant Wang Jinghong were once worshipped in the temple. In a recent issue of Gugong Bowuyuan guankan (2005:3), Wan Ming discusses a group of coloured sculptures of Zheng He unearthed in 1992 in the Taoist Xianying Temple in Xianqi village, Zhanggang township, Changle, Fujian province. Located on the spirit altar on the right side of the Front Hall of the temple complex, this group of coloured figures was dubbed "The Divine Officials who Patrol the Oceans". Since their excavation, the theory has prevailed that this group represents Zheng He, but there has been no research to back up this claim and no researcher has examined when these figures were carved or in what historical context. By examining the ritual conventions governing the clothing worn by officials in the Ming dynasty, Wan Ming establishes that the figures do indeed depict Zheng He. These sculptural pieces are the first discovery in China of any sculptural images of Zheng He, and they are also the oldest sculptures of Zheng He found anywhere in the world. Perhaps every major anniversary of Zheng He's voyages brings us slightly closer to an image of Zheng He that is more easily assimilated and admired, at the same time as the projected image of Zheng He is more distant yet seems to loom larger – a Genovese still waiting for a true Italian-style Columbus Day. [BGD] NOTES:[1] On 18 April 2005 Xinhua reported that a craftsman in Shaoyang city, Hunan province, had carved a bamboo slip version of China's Anti-Secession Law. The 86.4 cm long folding sheet comprises 72 slips, each 26 cm long and 1.2 cm wide, on which the Anti-Secession Law is written in traditional Chinese in a regular cursive style. Xinhua reported that, "The exquisite bamboo slip-sheet and the firm box blend deep emotion, consummate skill, and law, making the artwork a solemn, elegant and classic collection". [2] Three speeches delivered at the Seminar Commemorating the 600th Anniversary of Zheng He's Voyages to the Indian Ocean, held under the auspices of the Ningxia Academy of Social Sciences at the beginning of 2005 are included in the 1st issue of the quarterly Huizu yanjiu (official English title: Journal of Hui Muslim Minority Study) for 2005. The articles are: Ms. Li Dongdong, Minister of Propaganda of Ningxia, "Hongyang Zheng He jingshen wei jiakuai Ningxia fazhan gongxian" (Proclaim the spirit of Zheng He to accelerate contributions to Ningxia's development); Wu Haiying, Director of the Ningxia Academy of Social Sciences, "Zheng He jingshen ji qi dangdai yiyi" (The spirit of Zheng He and its contemporary significance); and Yang Huaizhong, Honorary Director of the Ningxia Academy of Social Sciences, "Zoujin Zheng He" (Approaching Zheng He). Wu Haiying's article cites Liang Qichao, and echoes Liang's sentiments, while the latter article stresses Zheng He's contribution as a Muslim and the role he played in establishing relations with the Muslim Middle East. [3] Menzies is, however, exhaustively cited in Chinese popular writings. The view that ancient Chinese mariners, if not Zheng He, did discover the Americas is, nevertheless, widely accepted in China, and a number of scholarly and popular texts present this case. See Lian Yunshan, Shei xian daoda Meizhou? Jinian Dong Jin Faxian Dashi daoda Meizhou 1580 nian (Who first reached the Americas? Commemorating the 1,580th anniversary of the Eastern Jin dynasty monk Master Faxian's arrival in the Americas), Beijing: Zhongguo Shehui Kexue Chubanshe, 1992; Ju Deyuan, Zhongguo xianmin haiwai da tanxian zhi mi (Riddles concerning the great maritime discoveries of the early Chinese), Beijing: Beijing Tushuguan Chubanshe, 2003. [4] Geoff Wade's article The Pre-Modern East Asian Maritime Realm: An Overview of European Language Studies provides the best bibliographic introduction to European language studies of Zheng He and the maritime history of East and Southeast Asia. [5] An exception is Geoff Wade's paper of 2003, "Ming China and Southeast Asia in the 15th Century: A Reappraisal", which describes the voyages and their motivation as "proto-imperialism". Li Yili, in a recent article (see references), characterises the voyages as imperial self-aggrandisement. REFERENCES:Chang Kuei-sheng, "Cheng Ho" entry in L. Carrington Goodrich and Fang Chaoying eds., Dictionary of Ming Biography 1368-1644, New York and London: Columbia University Press, 1976, pp 194-200. China Society of the History of Navigation (Zhongguo Hanghaishi Yanjiuhui) and the Organising Committee for the Commemoration of the 580th Anniversary of the Glorious Mariner Zheng He (Jinian Weida Hanghaijia Zheng He Xia Xiyang 580 Zhounian Choubei Weiyuanhui) eds., Zheng He shiji wenwu xuan (Selection of cultural relics associated with the achievements of Zheng He), Beijing: Renmin Jiaotong Chubanshe, 1985. Duyvendak, J. J. L., Ma Huan Re-examined, Amsterdam: Noord-Hollandsche Uitgeversmaatschappij, 1937. Duyvendak, J. J. L., "The True Dates of the Chinese Maritime Expeditions in the Early Fifteenth Century", T'oung Pao, 1938, Vol. 34, pp 341-412. Jin Qiupeng, "Yijin faxian zui zao de Zheng He xia Xiyang chuandui tuxiang ziliao: 'Tian Fei jing' juanshou chatu, in Wang Tianyou and Wan Ming eds., Zheng He yanjiu bainian lunwen xuan (A selection of papers commemorating a century of scholarship on Zheng He), Beijing: Peking University Press, 2004, pp 256-259. Ju Deyuan, Zhongguo xianmin haiwai da tanxian zhi mi (Riddles concerning the great maritime discoveries of the early Chinese), Beijing: Beijing Tushuguan Chubanshe, 2003. Lin Rechuan, Mingmo Qingchu de siren haishang maoyi (Private maritime trade in the late Ming and early Qing), Shanghai: Huadong Shidan Daxue Chubanshe, 1987. Li Yili, "Jinian Zheng He: Women ying zihao haishi zixing? " (Commemorating Zheng He: Should we be proud, or should he give us cause for reflection?) , Yanhuang chunqiu, 2005:1, pp 76-80. Lian Yunshan, Shei xian daoda Meizhou? Jinian Dong Jin Faxian Dashi daoda Meizhou 1580 nian (Who first reached the Americas? Commemorating the 1,580th anniversary of the Eastern Jin dynasty monk Master Faxian's arrival in the Americas), Beijing: Zhongguo Shehui Kexue Chubanshe, 1992. Lin Wo Ling (Lin Woling), Longyamen xinkao: Zhongguo gudai Nanhai liang zhuyao hangdao yaochong de lishi dili yanjiu (Long-ya-men Re-identified: A historical geography study of the two important junctions in the ancient Nanhai sea routes), Singapore: Nanyang Academy, 1999. Luo Maodeng, annotated by Lu Shulun and Lan Shaohua, Sanbao Taijian xia Xiyang ji tongsu yanyi (Popular romance of the journey to the Western Ocean of the Three Treasure Eunuch), Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe, 1985. Luo Rongqu, "Shiwu shiji Zhong-Xi hanghai fazhan quxiang de duibi yu sikao, Lishi yanjiu, Beijing, 1992:1. Menzies, Gavin, 1421: The Year China Discovered the World, UK: Bantam Press, 2002. Mills, K. V. G., and Roderich Ptak, Hsing-ch'a Sheng-lan: The Overall Survey of the Star Raft by Fei Hsin, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1996. Pelliot, Paul, "Les grands voyages maritimes chinois au debut du XVe siecle", T'oung Pao, 1933, No. 30, pp 237-452. Ptak, Roderich, and Karl Anton Sprengard eds., Maritime Asia: Profit maximisation, ethics and trade structure c. 1300-1800, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1994. Rivers, Capt. P. J., "1421" Voyages: Fact and Fantasy, Ipoh: Perak Academy, 2004. Tian Rukang (T'ien Ju-kang), "Cheng Ho's voyages and the distribution of pepper in China", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1981. Wade, Geoff, "Ming China and Southeast Asia in the 15th Century: A Reappraisal", paper presented at the Workshop on Southeast Asia in the 15th Century: The Ming Factor, 1-2 May 2003, Singapore. Wade, Geoff, The Pre-Modern East Asian Maritime Realm: An Overview of European Language Studies, ARI Working Paper no. 16, Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, 2003. Wan Ming, "Mingdai de Zheng He suxiang: Fujian Changle Xianyinggong chutu caisu zai tan", (Sculptural portraits of Zheng He of the Ming dynasty: Further study of coloured sculptures unearthed at the Xianying Temple in Changle, Fujian), Gugong Bowuyuan yuankan (Journal of the Palace Museum), Beijing, (June 2005) 2005:3. Wang Guanzhuo, Zhongguo gu chuan tupu (Illustrated compendium of ancient Chinese ships), Beijing: Sanlian Shudian, 2000. Wang Gungwu, "China and Southeast Asia 1402-1424" in J. Chen and N. Tarling eds., Social History of China and Southeast Asia, Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1970. Wang Tianyou and Wan Ming eds., Zheng He yanjiu bainian lunwen xuan (A selection of papers commemorating a century of scholarship on Zheng He), Beijing: Peking University Press, 2004. Zheng Hesheng and Zheng Yijun eds., Zheng He xia Xiyang ziliao huibian, Jinan: Qi-Lu Shushe, 1983. Zhang Jian, "Zheng He hanghai tu fuyuan", Sichuan wenwu (Sichuan cultural relics), 2005:2, pp 80-83. Zhou Shide, "Cong Baochuanchang tuogan de jianding tuilun Zheng He baochuan" (Confirming that the hypotheses regarding Zheng He's treasure ships in light of the tiller discovered at the treasure ship drydock), Wenwu, Beijing, 1962:3. |