|

ARTICLES

To Dig or Not to Dig | China Heritage Quarterly

To Dig or Not to Dig: Qianling Mausoleum in the Spotlight Again

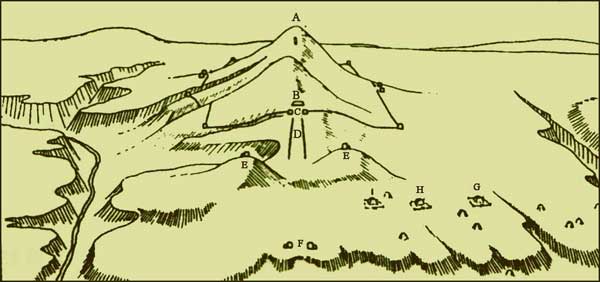

Fig. 1 Pre-modern style painting showing the layout of the Qianling complex. Source: Cover of the journal Qianling wenhua yanjiu (Cultural Research on Qianling).

Empress Wu (Wu Zhao, c.627-705) was the only woman ever to have ruled China directly and to have founded her own dynasty, albeit short-lived. She was also the only woman in Chinese history to have assumed the title 'emperor' (Zetian huangdi, Emperor Zetian), unlike other imperial women who effectively ruled but only in their capacity as empresses-dowager.

Empress Wu's dynasty, titled the Zhou (690-705), was legitimated through idiosyncratic rituals drawing on Buddhism; she even invented Chinese characters to give textual distinction to her innovations in state ideology. Ultimately her years of direct rule proved to be only a tumultuous interregnum in the history of the Tang dynasty (618-907). Despite the ruthlessness which characterised her rise to power, she limited her choice of victim to those members of her own family, in-laws and officials and generals who stood between her and total power. The fact that she frequently issued decrees announcing changing in her reign title (nianhao) also automatically entailed the proclamation of general amnesties (dashe), which cancelled many of the execution notices she signed.

(click on image to viewer large size map)

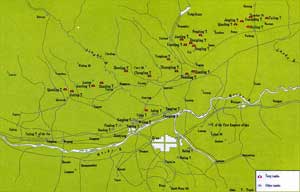

Fig. 2 Map showing the location of Tang dynasty mausolea in the Guanzhong plain. Source: Xi'an: Legacies of ancient Chinese civilization, Beijing: Morning Glory Publishers, 1992, p.227.

At the end of June 2006, the Qianling Museum in Shaanxi province staged a conference to commemorate the 1300th anniversary of the interment of Empress Wu at Qianling. Meaning 'Mausoleum of the Heaven Hexagram', Qianling is only one of the 18 mausoleums of the 20 emperors of the Tang dynasty (618-907) scattered across the Guanzhong plain, China's 'Valley of the Kings'. The Guanzhong plain, which and lies to the north-east of Xi'an, the provincial capital of Shaanxi, and today embraces a number of counties, is not only the location of the mausoleums of emperors of both the Western Han and Tang dynasties, but also of hundreds of 'satellite' tombs belonging to members of the imperial families, as well as leading civilian and military officials. The mausoleums of the Tang dynasty's emperors, unlike those of the Western Han, are not characterised by large earth tumuli erected on the plain, but are built into the sides of the mountains that ring the plain. As can be seen from correlating the map (Fig. 2) and the information contained in the table below, the tombs are not arranged chronologically, although the layout of each individual tomb complex did conform to the sumptuary regulations of the Tang dynasty. The Tang mausoleums on the Guanzhong plain are:

| Xianliang tomb of Emperor Gaozu (Li Yuan, r.618-626), located northeast of present-day Sanyuan county. | Fengling, tomb of Emperor Shunzong (Li Yong, r. 805), located northeast of present-day Fuping county. |

| Zhaoling, tomb of Emperor Taizong (Li Shimin, r.626-649), located northeast of present-day Liquan county. | Jingling, tomb of Emperor Xianzong (Li Chun, r.806-820), located northeast of present-day Pucheng county. |

| Qianling, tomb of Emperor Gaozong (Li Zhi, r.649-83) and Empress Wu Zetian, located northwest of present-day Qianxian county. | Guangling, tomb of Emperor Muzong (Li Heng, r.821-824), located north of present-day Pucheng county. |

| Dingling, tomb of Emperor Zhongzong (Li Xian, 684, 705-710), located northwest of present-day Fuping county. | Zhuanling, tomb of Emperor Jingzong (Li Zhan, r.824-826), located northeast of present-day Sanyuan county. |

| Qiaoling, tomb of Emperor Ruizong (Li Dan, r.684, 710-712), located northwest of present-day Pucheng county. | Zhangling, tomb of Emperor Wenzong (Li Ang, r.826-840), located northwest of present-day Fuping county. |

| Tailing, tomb of Emperor Xuanzong (Li Longji, r.712-756), located northwest of present-day Pucheng county. | Duanling, tomb of Emperor Wuzong (Li Yan, r.840-846), located northeast of present-day Sanyuan county. |

| Jianling, tomb of Emperor Suzong (Li Heng, r.756-762), located northwest of present-day Liquan county. | Zhenling, tomb of Emperor Xuanzong (Li Chen, r.846-859), located northwest of present-day Jingyang county. |

| Yuanling, tomb of Emperor Daizong (Li Yu, r.762-779), located northwest of present-day Fuping county. | Jianling, tomb of Emperor Yizong (Li Cui, r.859-873), located northwest of present-day Fuping county. |

| Chongling, tomb of Emperor Dezong (Li Shi, r.780-805), located northwest of present-day Jingyang county. | Jingling, tomb of Emperor Xizong (Li Xuan, r.873-888), located northeast of present-day Qianxian county.

|

The last two emperors of the Tang dynasty, not listed above, were buried in today's Henan and Shandong provinces, respectively.

The two largest Tang mausoleums are Zhaoling and Qianling. These tomb complexes belong respectively to Li Shimin, the second Tang emperor, known as Taizong (600-49, r.626-649), who oversaw one of China's greatest periods of cultural and political accomplishment, and to Empress Wu and Gaozong (name: Li Zhi, 628-683, r.649-83), Empress Wu's ineffectual husband and the third Tang emperor, from whom she wrested power after he succumbed to a stroke.

Layout of Qianling Mausoleum

Fig. 3 Line plan of the arrangement of Qianling. Source: Kimura Takashi, Qianling wenhua yanjiu, vol.1, p.57.

Empress Wu directed the construction of Qianling, which began in 683, just after the death of Emperor Gaozong in Luoyang (the provincial capital of present day Henan), which Wu Zetian preferred to Chang'an as her capital. It was Gaozong's last request that he be buried on the Guanzhong plain, and Empress Wu saw that this request was carried out, even though a number of her advisers, including the poet Chen Zi'ang, suggested that the imperial necropolis outside the Eastern Capital, Luoyang, was a more desirable location. Empress Wu despatched geomancers to select an appropriate site on the Guanzhong plain, and they selected Liangshan, a mountain rising to 1069 metres above sea level at the plain's edge and located 80 kilometres from Chang'an.

Fig.4 General view towards Qianling along spirit way ( shendao).

Like other imperial mausoleums, Qianling comprised a complex of underground chambers, while the surface structures included monumental gates, a long spirit way lined with stone statuary, a large enclosed mortuary garden, memorial halls, chapels, lodges, shrines and imperial quarters where the souls of the deceased monarchs could eat and sleep. (Figs. 3 & 4) The complex was constructed by teams of soldiers and labourers working around the clock for seven months, and Emperor Gaozong was buried there in 684. At the conclusion of the funeral, Empress Wu broke with precedent that proscribed the erection of stone epitaphs before imperial graves and erected for her late husband a record of his achievements. This was placed outside Red Bird Memorial Gate (Zhuquemen) at the mausoleum. The roughly square memorial garden which is the enclosed sanctuary housing the concealed entrance to the subterranean tomb measured approximately 1,500 metres along each side.

Fig. 5 Photograph showing a stone horse guarding the spirit way ( shendao) leading to the Qianling Mausoleum. Source: Luo Zhewen, China's imperial tombs and mausoleums, Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1993, p.85.

Fig. 6 Photograph showing a stone lion guarding the spirit way ( shendao) leading to the Qianling Mausoleum. Source: Luo Zhewen, China's imperial tombs and mausoleums, Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1993, p.86.

Fig. 7 Photograph showing stone animal guarding the spirit way ( shendao) leading to the Qianling Mausoleum. Source: Xi'an: Legacies of ancient Chinese civilization, Beijing: Morning Glory Publishers, 1992, p.235.

The 'spirit way' (shendao) (Figs. 5, 6 & 7) leading to the outer precincts of the complex is more than one kilometre in length and the stone sculptures of fabulous beasts, zoologically known animals, attendant officials and a guard of honour lining it reflect the cosmopolitanism of the Tang dynasty. These examples of monumental art can still be admired today and many reveal clear influences of Western Asian royal masonry, notably that of Persia. A large retinue of stone figures representing ambassadors from more than sixty countries still stands in one sanctuary within the complex, although these figures lost their heads to tomb vandals during the mid- and late-Ming dynasty.

In 705, the Zhou dynasty which Empress Wu Zetian established after her husband's death was brought an end, and in 705 Emperor Zhongzong restored the Tang. Empress Wu was imprisoned in Shangyang Palace where she died at the end of that year. Before her death, she summoned Emperor Zhongzong to her side and requested that she be buried together with her former husband. After her death, there was great opposition to Wu Zetian's last wish, but Emperor Zhongzong finally stifled debate and buried her at Qianling in early 706.

The Qianling Conference

The recent Qianling conference not only focused attention on the achievements of Empress Wu, but saw the issue again raised of whether or not to excavate Qianling Mausoleum. Surveys of the site suggest that the tomb has not been robbed. Tourism officials in Shaanxi remain eager to excavate both burial chambers in this mausoleum and as well as the tomb of Qin Shihuang, believing both sites to be untouched treasure troves that will rival the pits housing the terracotta armies of Qin Shihuang as tourist attractions.

The curiosity and determination of those with a tourist-oriented agenda is piqued by a statement in the last will of Emperor Gaozong contained in the text of his epitaph at Qianling, in which the emperor requests that his most highly prized paintings and calligraphy be placed in the tomb. Whether or not Empress Wu, who organised and oversaw her husband's burial and erected the epitaph that broke with Tang sumptuary regulations, fulfilled her husband's dying wish remains a matter of conjecture, as her propensity for acting with perversity is well attested in the historical record. Few, if any, original paintings on silk or paper survive from the Tang dynasty, and the discovery of previously unknown examples would be miraculous. However, the tomb chamber that putatively contains such valuable material would need to be hermetically sealed from the atmosphere and underground influence to have survived. Archaeologists would also have to ensure that the seal of the burial chambers was not broken on effecting entry if they are not to destroy these hopefully well-preserved works within an instant.

The Empress with No Epitaph

Fig. 8 Photograph showing the 'stele without characters' ( wuzibei) of Empress Wu Zetian at Qianling. Source: Xi'an: Legacies of ancient Chinese civilization, Beijing: Morning Glory Publishers, 1992, p.230.

The fact that Empress Wu seems to have rested content with erecting a stele bearing no inscription (wuzubei) as her own epitaph at the mausoleum is often interpreted as clear proof of her arrogance. (Fig. 8) However, like so many of the stories surrounding Empress Wu and her shared mausoleum, there seems to be no basis for this interpretation. The 'stele bearing no characters' was only classified as an unusual form of epitaph in late imperial epigraphic studies, prior to which the monument with the plain surface at Qianling was not described as a epitaph. Moreover, the plain monument would have been erected by Emperor Zhongzong, not by Empress Wu. She had broken with precedent in erecting an epitaph for Emperor Gaozong, and Emperor Zhongzong in turn was probably aiming for monumental symmetry in erecting this enigmatic structure on her behalf. Moreover, any description of her achievements that conformed to Tang protocol could only have been mendacious and so finally no inscription could ever have been carved on the stone.

In the Shadow of Guo Moruo

At the Qianling conference, it was archaeologists, cultural heritage officials and scholars, rather than tourism officials, who engaged in heated discussion with fellow professionals regarding the issue of excavating Qianling. Officials from the Shaanxi Provincial Administration of Cultural Heritage and Qianling Museum expressed a willingness to proceed with the excavation if suitable technology and sufficient labour were made available to them. These two organisations outlined their interim plan for the conservation and restoration of the surrounds of Qianling Mausoleum. In the 1950s and 1960s, China's pioneering archaeologist and historian Guo Moruo (1892-1978) had pressed enthusiastically for the excavation of Qianling, and in 1958 archaeologists succeeded in excavating the underground passage leading down to the sealed main burial chamber under Liangshan Hill.

Guo Moruo was imbued with the myth and romance of Wu Zetian. He had written a stage play extolling her intellectual and political strengths and virtues. Guo's recasting of the lives of many Chinese rulers and historical personages conventionally deemed to be tyrants as paragons of the exercise of perfected power mingled elements of Thomas Carlyle and Friedrich Nietzsche. Guo's interpretations lent intellectual authority to Mao Zedong's romantic vision of himself as the heir of Qin Shihuang, Emperor Han Wudi and Empress Wu. Despite Guo Moruo's prestige and influence in the period prior to the Cultural Revolution, the State Bureau of Cultural Relics opposed the many applications to excavate Qianling Mausoleum and ensured that the State Council enact legislation preventing the tombs of rulers from being excavated without permission from China's highest legislative body. Much of this was the result of the unfortunate excavation in 1956-58 of Dingling, an imperial mausoleum of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644).

The Hubris of Dingling

Although Guo Moruo's collation and interpretation of inscriptions on oracle bones still remain highly regarded by archaeologists, his reputation as a field archaeologist is tarnished by the scandals associated with the excavation of Dingling, the mausoleum of the Wanli Emperor (r.1573-1620) of the Ming dynasty located in the Ming Tombs valley north-west of Beijing. That excavation and its attendant history have been characterised as 'a tragedy' by Yue Nan and Yang Shi in their documentary work titled Fengxue Dingling (translated into English as The dead suffered too: The excavation of a Ming tomb, Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1996). The botched excavation of Dingling in 1956-58 was never formally approved, many of the artefacts were destroyed in the Cultural Revolution and the excavation report was only cobbled together from notes by survivors of the excavation in 1986.

Formal approval from the State Council had only been given for the excavation of a nearby mausoleum, Changling, the tomb of the Yongle Emperor (r.1403-1424). In October 1955 a request for instructions on the excavation of Changling, signed by Guo Moruo, Shen Yanbing, Wu Han (mayor of Beijing, a specialist in Ming history and a Yongle devotee), Deng Tuo, Fan Wenlan and Zhang Su was placed before Zhou Enlai. News of the request appalled Zheng Zhenduo, director of the Bureau of Cultural relics under the Ministry of Culture, and Xia Nai, deputy director of the Institute of Archaeology under the Chinese Academy of Sciences, who knew that China did not have the technology to undertake such an excavation, and they attempted to persuade Wu Han, vice-mayor of Beijing who had initiated the request, to withdraw it. They also requested that the premier not sign the authorisation to excavate. Under the cultural weight of Guo Moruo, who served for a time as Mao Zedong's 'muse', however, Zhou Enlai caved in and the excavation of Changling was authorised, with an unwilling Xia Nai placed in charge of it. However, Dingling was excavated between 1956 and 1958 as a 'trial excavation' only, in order to examine stratagems for determining the layout of the yet to be excavated Changling.

The final stages of the almost unintentional excavation of Dingling were disastrous. Lacking the technology to process and preserve adequately the timber articles and textiles which were unearthed, the team was busy attempting to save as best they could the bodies of the Wanli Emperor, his empress and concubines, when the Anti-Rightist Campaign began. The team was no longer under the Changling Excavation Committee headed by Xia Nai, but formed part of a new collective unit under the control of the group preparing to establish the Dingling Museum intended to house the finds. The original team had been effectively sidelined. Xia Nai and the excavators were forced to put aside their all important final cataloguing and processing being conducted underground, in order to attend compulsory political meetings at the Academy of Science. While the excavators attended meetings, the excavated objects rapidly decayed.

On 6 September 1958, Xinhua News Agency released the story of the first excavation of an imperial tomb since the establishment of the People's Republic in 1949. The excavation of Dingling had been kept secret for nearly three years. When Xinhua reported the news, emulative groups imbued with the enthusiasm for socialist construction in China's countryside and the coming Great Leap Forward (1958) formed across rural China to undertake the excavation of identified imperial tombs that had rested dormant and neglected, except by tomb robbers, sometimes for millennia. In the same month, some of the major objects unearthed from Dingling were displayed in the rostrum by the northern gate of the Forbidden City.

Thereafter, events unfolded rapidly. Zhao Qichang, who had supervised much of the excavation, was sent as punishment to the countryside, away from the excavation site where work resumed on the cataloguing and measurement of all the unearthed objects for the excavation report. Zhao was the first victim at Dingling of the Anti-Rightist campaign. The workers preparing materials for the museum accelerated their work, thereby destroying more valuable objects. The Dingling Museum was scheduled to open on 30 September 1959, and the director of the museum ordered that the imperial coffins be thrown away, because plaster and cement replicas had already been prepared for display. The coffins were tossed into the gorge over the parapet of the wall enclosing the mausoleum. The remaining imperial skeletons were placed in a warehouse, but in 1966 they were incinerated in a public bonfire by local Red Guards. The excavation report only appeared in 1986, ten years after the Cultural Revolution decade ended. The report was prepared from notes concealed from the Red Guards by some members of the archaeological and museum teams.

Only on 12 December 2006 was it announced that a proper storehouse for the Dingling finds would be constructed in the third underground marble chamber of the Dingling mausoleum, and that the new three-storey facility occupying 3,000 sq m of floor space, will feature modern security and fire equipment, as well as temperature and humidity controls. No date for completion of the facility earmarked to cost RMB 26 million was provided, but Li Dezhong, deputy director of the Office for the Ming Tombs Area Administration, in announcing the news, said that the only recently completed above-ground facility housing the relics at the Dingling site had also failed to control temperature and humidity. Given the fact that it will take more than half a century to salvage what remains from the incompetent excavation of Dingling, China's archaeologists are naturally cautious about proceeding with further destructive excavations of imperial mausoleums.

Arguments Presented at the Qianling Conference

China today presents an utterly different political landscape from that of the 1950s-1970s, and the advances in archaeological technology over the past half a century have been many. However, an over-confidence in present abilities to handle the problems presented by an unknown situation—the condition and layout of the underground interior of Qianlingis—is also a dangerous thing. Ma Wenting, Party committee secretary of the Qianling Museum, stressed at the conference that 'the fever for excavating Qianling' has passed, but added that the tomb must contain a staggering wealth of artefacts. This latter conjecture was corroborated by 83-year old Shi Xingbang, former director of the Shaanxi Provincial Archaeology Institute and head of the Shaanxi Archaeology Society. Shi Xingbang had supervised the excavation of the Tang dynasty underground crypt at Famensi Temple, sealed up twenty years after Qianling, and the spectacularly beautiful and academically important treasures found there were beyond the wildest hopes of the excavating team. Shi stressed that Qianling is the only Tang dynasty mausoleum that has not been plundered, and so skeletons, various silver and golden articles, ceramics, carpentry and silk items inside the tomb would be invaluable for archaeological purposes. Although the structure of the tomb remains sound, he argued that nobody knows what the tomb is like inside or whether earthquakes, mildew and the environment have affected its contents. Shi Xingbang remains confident that archaeologists today could handle all contingencies presented by the excavation.

However, many attending the conference were opposed to Shi Xingbang's views, including Su Bai, archaeology professor emeritus from Peking University, who believes that given China's limited scientific technology, the environment 1,000 meters underground is comparatively stable and should be allowed to continue to preserve the tomb and its objects undisturbed. The State Administration of Cultural Heritage is also opposed to the excavation of Qianling, holding also to the principle that preservation and salvage are more important than digging. Shaanxi lodged requests to excavate Qianling in 1986, 1994 (this proposal was drafted by Shi), and in 2000.

Seventeen of the Tang imperial mausoleums are reported to have been robbed in the late-Tang and subsequent Five Dynasties period, but there is no record of Qianling having been successfully plundered. A 1958 survey of the tunnel leading down to the burial chambers confirmed the view that Qianling had not been robbed. The director of the Qianling Museum, Fan Yingfeng told the conference that the written records suggest that the imperial catafalque was located in the central underground chamber and that the coffin was encased in jade that prevents decay. On the basis of written records, some scholars at the conference suggested that the burial chambers contain more than 800 tonnes (dun) of ancient paintings, silks, lacquer objects, ceramics, timber, silver, gold and jewelled articles.

Advocates of excavation also used the 'politically correct' argument that the excavation of Qianling would constitute a salvage excavation because the area is prone to earthquakes, but that line of reasoning cannot be backed up with geological statistics. To add weight to their Tutankhamen fantasies, the advocates of excavation cited the wealth of treasures found in the five excavated satellite tombs of Qianling, which has a total of 17 identified satellite tombs. Only three of the five are open today—the tombs of the Yide and Zhanghuai Princes and the tomb of the Yongtai Princes, which were excavated in 1960 and 1970. Although these contained valuable tricolour wares, the major discoveries were the valuable tomb frescoes. (Fig. 9)

Liu Qingzhu, head of the China Archaeology Society, and other leading Chinese archaeologists were quick to question the claims made on behalf of Qianling's treasures. Liu pointed out that, despite the claims, the satellite tombs are unspectacular, aside from their murals, while Chen Jingyuan pointed out that Emperor Gaozong was buried in the Qianling complex only seven months after construction of the tomb complex was initiated, a very short time in which to assemble burial goods especially when compared with many other Chinese imperial complexes that were constructed and filled over decades. Moreover, in 683 Emperor Gaozong had issued a memorial calling for 'the exercise of thrift in the matter of imperial burials' and, unlike Qin Shihuang and many other emperors, he did not spend time preparing for the hereafter.

Fig. 9 Scene of a polo match. Detail from murals in tomb of the Zhanghuai Crown Prince, a satellite tomb of Qianling Mausoleum.

Faith in the view that Qianling has not been robbed might also be misplaced. Several participants at the conference pointed out that the surveys conducted of the mausoleum were far from rigorous. It should be recalled that in 2001, as a result of preliminary survey work that found no evidence of tomb violation, archaeologists were so confident that the 2,000 year-old Laoshan royal tomb in western Beijing had not been robbed, that the opening of the tomb was directly televised on China Central Television. Excited midday viewers were disappointed to discover that the tomb had been effectively cleaned out by tomb robbers, and the on-the-spot reality TV program revealed that crime can pay.

The custodians of Qianling will probably have to rest content with preserving the above-ground environment surrounding the mausoleum. On 23 July 2006, Beijing qingnianbao (Beijing youth daily) reported that the nearby Zhaoling mausoleum of Tang emperor Taizong (Li Shimin) was suffering damage from illegally operating lime kilns in the tomb's vicinity. The Guanzhong plain is a threatened environment, and it may help to let sleeping emperors lie in peace. [BGD]

|