|

|||||||||

|

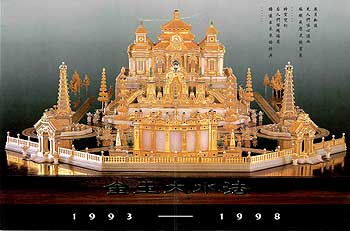

EDITORIALNo. 8, December 2006YUANMING YUAN, THE GARDEN OF PERFECT BRIGHTNESSThe Garden of Perfect Brightness, or Yuanming Yuan (Yuan Ming Yuan, also known in English as the Old Summer Palace), now constitutes an extensive public park just inside the northwest stretch of Beijing's Fifth Ring Road. It was part of an series of garden palaces and residences that covered an area including present day Peking and Tsinghua universities, as well as the Jade Spring Hill (Yuquan Shan) party retreat, the Summer Palace (Yihe Yuan), the Fragrant Hills (Xiangshan), the botanic gardens and various adjacent temples. Along with the Forbidden City and the Imperial Mountain Villa (Bishu shanzhuang) at Jehol (Rehe, modern-day Chengde), the Garden of Perfect Brightness was an integral part of imperial rule from 1726 (r.1723-1735), the year the Yongzheng emperor formally moved there, up to the assault by Anglo-French forces following the Second Opium War in 1860, which devastated the palaces and courtly residences of what is Haidian district today. Partially rebuilt in the 1870s and then finally dismantled so that the Summer Palace could be reconstructed in the 1880s, the Garden of Perfect Brightness remained a site of plunder until relatively recently. It is now celebrated as China's 'national ruin'; but the ruin park is also the centre of debates that touch on issues of heritage and the environment, preservation and restitution, as well as history and national identity. While some agitate for the garden palace, or at least part of it, to be rebuilt as part of a symbolic gesture to mark a China recrudescence, others have already constructed partial replicas outside Beijing (at 'First City Under Heaven' in Tongzhou, in Zhuhai near Macao, Shenzhen and Shenyang, for example). More recently, plans have been mooted for a full-scale mock-Yuanming Yuan to be built at Dongyang, Zhejiang province, by the Hengdian Corporation. In this issue we discuss recent debates surrounding the Garden of Perfect Brightness, as well as key works on the subject. We are also featuring some writing that is not readily accessible online, including Geremie R. Barmé's 1996 Morrison Lecture, 'The Garden of Perfect Brightness, a life in ruins' and 'A Case of Mistaken Identity', his study of the 'traitor' Gong Xiaogong, the man who supposedly led the foreign troops to the garden in 1860. We also discuss a recent stageplay and a major documentary film, both produced in Beijing in 2006, that take this contested imperial ruin as their theme.  'View of Distant Seas' (Yuanying Guan), winter 2000. Photo: Lois Conner. Tracer light by GRB. Between Ruination and Restoration Fig. 1 The only extant bridge in Yuanming Yuan. Photo: GRB. Heritage sites often generate controversy, but for obvious political and cultural reasons the Garden of Perfect Brightness elicits reactions from nearly everyone. While many heritage sites are restored to a presumed 'representative moment' in their history, the gardens in their dilapidated state have undergone ceaseless change, different in nature but no less radical from the days when they were an expanding and magnificent imperial demesne. The gardens, the exploitation of them and the debates surrounding them reveal in essence many of the central issues and lurking problems in China's quest to preserve its heritage. (Fig. 1) In August 2000, the Beijing city government approved plans for the restoration of the Garden of Perfect Brightness (Yuanming Yuan). The grounds of the once majestic and extensive series of palace gardens lived in and expanded by Qing-dynasty rulers from the time of the late Kangxi reign to the end of the Xianfeng reign (1700s to 1860) were dotted with audience halls, government offices, imperial residences, studies and libraries, as well as hundreds of pavilions, belvederes, studios, fountains and waterways covering approximately 352 hectares. The garden palaces now referred to as 'Yuanming Yuan' in Chinese is in fact the three connected gardens: Yuanming Yuan, Changchun Yuan and Qichun Yuan. In dynastic times the area was called 'The Five Gardens of Yuanming' (Yuanming wuyuan), comprising the three already mentioned as well as Xichun Yuan and Chunxi Yuan.[1] (Fig. 2)  Fig. 2 An imaginative artistic representation of the Yuanming Yuan prior to 1860. The series of marble 'Western Pavilions' (Xiyanglou) in the north-eastern corner of the Changchun Yuan gardens were designed by Jesuit missionaries during the reign of the Qianlong emperor (r.1736-1795). The ruins of these pavilions and their fountains are the most visible remains of what was quintessentially a Manchu-Han garden, and they are taken by many visitors as being representative of the Yuanming Yuan as a whole, even though in extent and architectural style they were of minimal importance. That the marble structures survived over a century of plunder (see Features, 'The Garden of Perfect Brightness, a life in ruins') has, ironically, made the Western Palaces the most famous symbol of the place and its ruination. The pavilion and fountains of 'View of Distant Seas' (Yuanying Guan) are what the art historian Wu Hung has called the 'national ruin' of China. (Fig. 3) It is also this building that is most widely copied by builders, digital designers and craftspeople. (Fig. 4)  Fig. 3 View of Distant Seas. Photo: GRB.  Fig. 4 A gold and jade representation of View of Distant Seas and the fountains, made by craftspeople working for the Shenzhen Huajing Yuan company, 1998. Indeed, the destruction of the garden palaces, attributed in toto to an Anglo-French Expeditionary Force in 1860, has become a leitmotif for the national humiliation China suffered during its 'modern period' (officially regarded as spanning the years 1840-1949). The razing of the palace gardens, and the extensive pleasure grounds, residences and parks in the area of Haidian was underscored by the destruction in 1900 by the Eight-Power Allied Expeditionary Force of many other rebuilt structures and noble residences. Only one bridge and the Zhengjuesi Temple survived into recent times. The Rise of Yuanming YuanThe site of the Garden of Perfect Brightness was recognized as a district-level 'unit for cultural protection' in 1960. However, interest in the Yuanming Yuan only began to increase as revolutionary Maoism waned. The Yuanming Yuan Study Society was established in the mid 1970s, and its concerned members realised that destruction of the site continued as farmers removed stones that remained scattered and buried throughout the site to construct houses, bridges and to line canals. As early as 1977, academics with expertise in history, architecture and the gardens like Wu Liangyong, Hou Renzhi and Shan Shiyuan were discussing the need for the remains to be protected and used as an educational resource.[2] (Fig. 5) Fig. 5 Cover of an early booklet produced by the Yuanming Yuan Management Office, 1994. Major earth moving projects were set in motion when the Yuanming Yuan Management Office was established. At an academic conference held in Beijing in 1980 to coincide with the 120th anniversary of the destruction of the Yuanming Yuan, a petition calling for the protection of the palace site was drafted. The first signatory of that petition was Song Qingling, the widow of Sun Yat-sen, Father of the Republic of China. In 1983, the State Council designated the Yuanming Yuan an historic garden site, but no protection order was issued, and in 1984, the Yuanming Yuan Study Society developed a plan for the partial restoration of the ruins of the Western Pavilions, as well as mooting longer term plans for the site as a whole. Yet it was only in 1988 that the area was included in the third group of major cultural sites under state-level protection and partially opened to the public as a tourism spot. It was this easy public access that also led to increased interest in the history and fate of the ruined gardens.   Figs 6&7 Newly constructed gates to the Yuanming Yuan and the Changchun Yuan with 'tiger-skin walls', 2000. Photo: GRB. In the 1990s, donations of funds by patriotic compatriots in Hong Kong allowed for the three garden-parks of Yuanming Yuan, Changchun Yuan and Qichun Yuan to be protected by a boundary of 'tiger-skin walls' (hupiqiang) of the kind used for imperial parks and hunting grounds (such walls are in evidence in the northwest corner of Peking University and at the Summer Palace). (Figs 6&7) However, on 20 October 2006, Beijing Youth News (Beijing qingnian bao) reported that the last stretch of the tiger-skin perimeter had just been completed. Thus, it had taken twenty years to sequester once again the former imperial precinct; moreover, it cost an estimated 400 million yuan to moved the 615 families and work units that had occupied parts of the gardens over the years. Unearthing the GardenIn the early 1990s, the Western Pavilions became a site used by state and party leaders to recall the humiliations of the past and to celebrate the regnant nation (and it featured prominently in the 1997 return of Hong Kong to mainland control). In 1993-1994, the government proposed using foreign capital to construct a miniature replica of the Yuanming Yuan on the site of the original, and draft plans and initial archaeological surveys were made. This plan focused on three areas in the southwest section of the site—the Garden of Aquatic Plants (Zaoyuan), the Thirteen Locales (Shisansuo) and the Mountain and River Retreat (Shangao Shuichang). To comply with state regulations on cultural relics protection, Beijing Municipality commissioned archaeologists from the Beijing Cultural Relics Institute to survey and excavate the sites and prepare a draft plan. Shortly thereafter, an area of more than 4,600 sq m at Zaoyuan was excavated between September and December 1994. The entire building complex in the southwest corner of the garden was uncovered. Although all the buildings had been levelled, the outline of the stone paths and ponds could still be seen at the time of the survey.The Beijing government's proposal to launch incursive reconstruction project in the garden, however, resulted in a public outcry and the proposal was scrapped. However, the idea was floated again in 1998 at the Beijing Municipal Political Consultative Conference, and in May 1999 the Beijing government authorised the Beijing City Planning Authority to draw up a draft plan for the Yuanming Yuan site. The debate spread in the mass media after the historian Wang Daocheng and Chen Liqun voiced their opposition, and the novelist Cong Weixi published a rebuttal in Beijing Evening News (Beijing wanbao).[3] Fuelled by enthusiasm for Beijing's 2008 Olympic bid, the plan was, however, eventually approved in August 2000. Authorities on ancient architecture and the environment were quick to denounce it again. The contretemps about whether the park be preserved as it was, partially restored, partially rebuilt or fully restored raged in the print media for some months, and every time a new incident involving the gardens occurs the familiar battle lines are redrawn and the debate unfolds anew. Xu Pingfang, head of the China Archaeology Society, and originally head of the Institute of Archaeology under the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), voiced the opinion that the Yuanming Yuan should be preserved as a large excavated archaeological site, which will reveal the dimensions and topography of the original gardens. Liang Congjie, a member of the Political Consultative Congress and founder of the citizens' group 'Friends of Nature', warned that tourism at a site many times larger than the Summer Palace would pose an environmental threat that had to be anticipated. Luo Zhewen, head of the Ancient Architecture Group of the State Cultural Relics Bureau, argued that only a small and representative section with historical significance should be restored, and that it was absurd to envisage, for example, rebuilding the Western Pavilions buildings. Luo's proposals can be seen as a tacit endorsement of the original, more modest 1994 plan. During 2005-2006, Wang Daocheng, along with Ye Tingfang, a researcher in the Foreign Literature Research Institute of CASS, continued to be among the most publicly outspoken opponents of plans to rebuild or restore part of the gardens. In a series of speeches and articles over recent years they have individually declared that the ruins are themselves of key heritage value and that they must be protected. Such scholars have also strenuously argued that the present quality of workmanship would be far inferior to the artisanship originally devoted to the numerous palaces and buildings (see 'The Lei Family Builders' in Articles).   Figs 8&9 Tourist attractions in Yuanming Yuan. Photo: GRB. While the debates have continued, the single extant building dating from the Yuanming Yuan, Zhengjuesi Temple, has been restored. Proximate to the north wall of Peking University the temple was an elegiac ruin occupied by a boiler factory. It has now been completely refashioned, and as a result it evinces none of the powerfully moving ruination of the past or the heritage value of the decrepit original. It has, in short, become yet another showcase 'Qing-era temple' of the type quite common in the capital. Covering the GardensThe clash between advocates in favour of protecting Yuanming Yuan as a heritage site, its ruins frozen in time, its role in patriotic education assured, and those who would either restore it in part or completely, or indeed those who vaunted the 1990s policies—influenced by the radical marketization of the society—that the park should make money through customer-pays entertainments (theme rides, zoos, boat rides and so on) came to a head in April 2005. (Figs 8&9)  Fig. 10 A Qianlong-era painting of 'Tantan dangdang' on silk, one of the 'Forty Views of Yuanming Yuan'. Source: Yuanming Yuan sishi jing tuyong, Beijing: Yuanming Yuan, 1991. The park authorities had already been busy with 'restoring' sections of the original area of the Yuanming Yuan from 2004, in particular the area around the imperial audience hall (Zhengda Guangming) and the emperor's residence and the nine islands that surround the lake behind it (Jiuzhou Qingyan). During this process the extensive fish ponds of 'Tantan Dangdang' (Figs 10&11) and the swastika-shaped studio 'Peace in All Directions' (Wanfang Anhe), a studio favoured by Yongzheng, were also unearthed and their foundations restored, often with more bricks and mortar than more stringent heritage experts would have approved. Some thirty original bridges, or parts thereof were also featured in this process, not as functioning structures but as repaired rumps and remnants. (Fig. 12)  Fig. 11 'Tantan dangdang' unearthed and partially restored, winter 2006. Photo: GRB. Then in November 2004, without due regard for environmental considerations, and anxious to preserve the water-filled lakes and waterways of the areas of the garden open to the public (the Changchun Yuan and Qichun Yuan), the park management had the lakes drained and the lake beds covered in plastic sheeting. Given the increasingly dire water shortages of the capital, and concerned that the appeal of the gardens to the paying public be maintained, the management reasoned that this would prevent lake water from seeping away. The planned cost of the project was 30 million yuan (some AUD$5 million). Given the public and expert attention focused on what is the largest unused area of land, and one of the most politically sensitive sites, within the Fifth Ring Road of China's capital, it is not surprising that there was an outcry over a project for which no environmental impact assessment had been prepared. Concerns were voiced that the living waters, cut off from the complex underground water system of the once marshy Haidian district, would become 'dead water' and that the biodiversity of an already endangered area would be further compromised.  Fig. 12 A restored bridge near the site of the former imperial apartments, Yuanming Yuan, summer 2005. Photo: GRB. From 1998, lakes, waterways and rivers in Beijing were increasingly being lined with cement to contain water, creating a host of new problems for conservationists. The Yuanming Yuan case showed that plastic sheeting had now replaced cement since 2002 when outcries over its use had forced the Beijing Water Resources Bureau to abandon the strategy. In April 2005, the Yuanming Yuan management was ordered to a halt and in May expert witnesses were invited to address a public investigation held by the State Environmental Projection Administration into the ill-conceived plan. It was the first such hearing of its kind and the decision that eventually resulted—to stop the folly of sheeting the lakes—was widely hailed as a rare victory for the environment and for nascent democratic processes.  Fig. 13 Dry waterways at Yuanming Yuan, Lois Conner, winter 2004. With public attention and media voracity focused on the gardens, it was also reported that for years the Yuanming Yuan management, while raising a great hue and cry about preserving the gardens as a patriotic site and a symbol of past humiliations, had been leasing out parts of the gardens for undisclosed sums to people in the arts and the legal profession. It was widely known in the arts community that two 'comic cross-talk' (xiangsheng) performers had rented the 'fairy isle' in the middle of the Lake of Plenitude in the mid 1990s, while a large area next to the formal entrance to the Yuanming Yuan had been leased out for the building of a series of offices and exclusive apartments (the Wangchun Yuan Villas).[4] The 'plastic sheeting incident' and public outrage at the commercial avarice of the garden authorities led to renewed debates about the fate and function of the long-suffering Garden of Perfect Brightness and it inspired, in 2006, a new environmental play (see 'On Stage & Screen' in Features).  Fig. 14 Dry waterways at Yuanming Yuan, Lois Conner, winter 2004. A Paradise LostWith the various films, TV documentaries and constant discussions, The Garden of Perfect Brightness has increasingly figured in the popular imagination. It also brings a specialist and generalist interest in issues related to cultural heritage and the fragile nature of China's built (or ruined) heritage into clear focus. (Figs 15&16) Fig. 15 Detail form a Qianlong-era painting on silk of the imperial audience hall, 'Zhengda Guangming'. Source: Yuanming Yuan sishi jing tuyong, Beijing: Yuanming Yuan, 1991. Amidst the continuing and always rancorous debates surrounding the fate of the original site of the Yuanming Yuan, the Zhejiang Hengdian Corporation announced in the summer of 2006 that it would invest two billion yuan and expend five years to rebuild the gardens entirely, but in Zhejiang. 'While the Yuanming Yuan in Beijing represents the gardens following the devastation of 1860, our project will recreate Yuanming Yuan as it was at the height of its glory,' a company spokesperson said. The project will create a theme garden of 350 hectares that, as the Hengdian publicists point out, is as big as the original. While the Garden of Perfect Brightness was built over nearly a century, Hengdian Company wants to finish its work within five years, perhaps to catch the 150th anniversary of the initial destruction of the gardens and surrounds in 1860. Given the proliferation of theme parks in China (there are an estimated 2500 such sites in the country according to a recent count, 70% of which are losing money and only 10% of which turn a profit), Hengdian's plan seems to meld commercial bravado with a desire to make a patriotic investment. Ruan Yisan, a professor at Tongji University's Centre of Research into Historically Famous Cultural Cities, said that such a project 'was of little value'.  Fig. 16 Government-erected plaque at the site of the imperial audience hall, 'Zhengda Guangming', summer 2005. Photo: GRB. The US-based academic Wong Young-tsu's book A Paradise Lost[5] was published in Chinese translation and the effect of its title is reflected in the rhapsodies for the gardens found in Zhang Guangtian's 2006 play, 'Yuanming Yuan' (see 'On Stage & Screen' in Features in this issue) in which the garden gains a mytho-poetic status as somehow representing the essence of the Chinese national spirit. For many years, the Manchu-Qing rulers were excoriated for their corrupt rule. Even the height of the Qianlong reign, during with the gardens flourished, was excoriated by political leaders and historians of modern China as being emblematic of 'feudal' decadence. However, the revived importance of the Manchu-Qing era in contemporary China, after decades of political obloquy, is perhaps an indication that finally the last dynasty and its complex cultural heritage are being 'domesticated' into a contemporary Chinese identity. [GRB] This issue of China Heritage Quarterly was produced under the aegis of my Federation Fellowship project, funded by the Australian Research Council and ANU. * My thanks to Dane Alston for his help in scanning images for this issue, and to Jane Macartney of The Times Beijing Bureau for a copy of the DVD of the film Yuanming Yuan. My colleague Bruce Doar also provided key information on the recent history of the gardens. Bruce and I also wish to acknowledge and thank Jude Shanahan, who designs and produces our publication. Notes:[1] Zhang Enyin, 'On the origins of "The Three Mountains and Five Gardens"' ('Sanshan wuyuan' shuoyuan) in his Sanshan wuyuan shilüe, Beijing: Tongxin Chubanshe, 2003, pp.1-5. [2] 'A written exchange concerning the preservation of the remains of Yuanming Yuan and how to use the past to serve the present' (Guanyu Yuanming Yuan yizhide baohu ji gu wei jin yong deng wentide bitan), April 1977, collected in Wang Daocheng, ed., Yuanming Yuan—lishi, xianzhuang, lunzheng, Beijing: Beijing Chubanshe, 1999, vol.1, pp.452-65. [3] See Wang Daocheng, ed., Yuanming Yuan—lishi, xianzhuang, lunzheng, vol.2, pp.772-806. [4] 'Yuanming Yuan responds to [inquiries about] renting out the lake island' (Yuanming Yuan huifu huxindao chuzu) and 'Villas built inside Yuanming Yuan?' (Yuanming Yuannei jian bieshu?), Beijing qingnianbao, 20 May 2005. [5] Young-tsu Wong, A Paradise Lost: the imperial garden Yuanming Yuan, Honolulu: Hawai'i University Press, 2001. See also Che Chiu Beng, Yuanming Yuan: Le jardin de la clarté parfaite, Besançon: Éditions de l'Imprimeur, 2000. |