|

||||||||

|

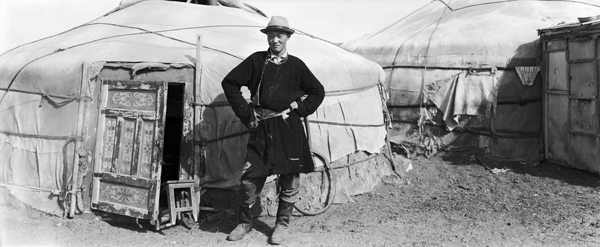

ARTICLESOn the Wickedness of Being NomadsOwen LattimoreT'ien Hsia Editorial Note: The Editors welcome a frank and honest expression of opinions, but do not hold themselves responsible for them. China Heritage Quarterly Editorial Note: In light of the continued unsettled ethnic affairs of the People's Republic of China, the following essay published nearly seventy five years ago offers some interesting perspectives and insights. Many of the issues related to immigration, nomadic lifestyles and environmental degradation which feature so prominently today were already in clear evidence during the middle years of the Republic of China. Minor editorial changes have been made to this article in line with our in-house style. All policies towards the Mongols, whether Chinese, Soviet or Japanese, appear to start from, a common premise: that something must be done about the nomadism of the Mongols. If, in other words, the Mongols can only be cured of being Mongols, all will be well—at least, for China, the Soviet Union or Japan. My own knowledge of Outer Mongolia is admittedly inadequate, since it is entirely derived from refugees who have fled from Outer Monoglia because they did not like the new form of government there. Nor have I, since 1930, been in the part of Inner Mongolia which overlaps into Manchuria, so that I have no first-hand knowledge of the Japanese policies initiated there under Manchoukuo. My remarks must therefore be based primarily on the part of Inner Mongolia which is included in the provinces of Chahar, Suiyuan and Ninghsia.  Mongolia (Mongol uls), 1997. Photograph by Lois Conner The underlying problems of Inner Mongolia are social and economic, more than political, although antagonisms between China and the Mongols usually take political forms. The interest of the Mongols, for geographical and climatic reasons, are as, predominantly pastoral as those of the Chinese are, or have been in the past, agricultural, and this for centuries has prevented satisfactory fusion between the two peoples. Chinese colonization of Mongol territory was in past history virtually impossible. The mobility of the Mongols, and the lack of 'nerve-centers' in Mongolia, in the way of cities that could be seized, paralyzing the economic and political life, made it unsatisfactory to send out expeditions to occupy and hold the country. The Mongols, on the other hand, in spite of their much smaller numbers, could always raid very effectively into China, occupying vulnerable cities and cutting vital arteries of administration and trade, such as roads and canals. Moreover Chinese agriculture was highly specialized. It was essentially an intensive agriculture, based on an economic exchange between comparatively small, hand-tilled farms and numerous, populous cities. Long-distance exchange of commodities was limited very largely to canal, river or coastal transport, except for goods (few of which, in the nature of things, were essential commodities) which would stand a high cost of transport. Grain, for instance, can be transported by cart only over a very limited distance; within a few days the animals which pull the cart eat up the whole value of the load. In Mongolia, river approaches hardly exist and canals are impossible, so that Mongolia under the old conditions could never have been made a producing area for the export of grain to China. Within Mongolia itself, the poor soil and arid climate did not favor a 'crowded' economy of numerous, well-peopled cities surrounded by closely farmed fields. Consequently, economic and social conditions confirmed the military and political conditions in preventing a shift of the Chinese population toward Mongolia. The introduction of mechanized transport started an economic revolution in Mongolia as well as in China. The effects in China were striking enough. Railways have destroyed the old north-south main line of long-haul commerce of which the Grand Canal was the artery, and have modified the importance of the Yangtze and other main lines of transport. An east-west 'draining' of China has been substituted, which makes the Treaty Ports the outlets of China's wealth and largely accounts for foreign domination of China's economic life. In Mongolia, railways favored foreign domination only indirectly; the immediate effect was to extend Chinese control. Cheap haulage by rail made Chinese colonization possible where it had never been successful before. Wherever frontier railways have been built, fed by the colonization of previously uncultivated Mongol lands, the 'economic distance' for the haulage of grain freights by cart from outlying districts to railhead has proved to be from about 100 to about 150 miles, depending partly on roads, subsidiary developments of various kinds, and other local conditions. Beyond these distances, colonization fails to "take hold" without further railway development. This at least is the conclusion indicated by a comparison of railways and colonization areas, notably in Manchuria but also in Chahar and Suiyuan. Railways not only increased the depth of Chinese penetration into Mongolia. They enormously increased the rate of colonization; and the social and economic results of this were of primary importance. In the comparatively restricted areas of pre-railway penetration into Mongolia—among the Kharchins of southern Jehol, for instance, and the Tumets of southern Suiyuan—a certain amount of fusion was possible. Chinese economic and social standards prevailed over those of the Mongols, but the rate of change was leisurely enough to permit many Mongols to learn Chinese, take up agriculture, and form a society Chinese in its main elements, but preserving a healthy regional pride and unashamed of its partly Mongol origins—indeed, proud of them, for on the whole the Mongols of these regions were wealthier and had a higher standard of living than the incoming Chinese. The settled Mongols of these marginal regions tended to preserve the Mongol language as a secondary language; and they modified the Chinese agricultural economy by continuing to keep a comparatively large number of livestock. At the same time, many frontier Chinese in contact with them tended to learn partly Mongol ways of life. The resultant amalgamated society was capable of an indefinite expansion into Mongolia, wherever the range of trade and exchange permitted. The formation of such a composite society, however, requires time for slow adaptation. Its growth requires generations, rather than years or even decades. The railways changed all that. The new, overbearing economic forces which they introduced demanded results. If there was not time to adapt the suddenly expanding Chinese population to the old social and economic conditions, then the old conditions must be smashed and new conditions created which would be subservient to the new economic forces. Something of the same kind of change, from slow adaptation to the steamroller imposition of new standards, took place in the transition from the pre-railway to the post-railway colonization of the American West. The result, in Mongolia, was to turn the Mongols abruptly into a victimized people. Wherever the Chinese came, the Mongols had to get out. They suddenly found themselves stigmatized as a 'backward' people, 'too primitive' to take up the new Chinese agriculture—although they had not been too primitive to take up the old 'mixed' border economy. An entirely artificial line was drawn between 'civilized' agriculture and 'primitive' pastoral economy, dependent on livestock. To be a nomad was a kind of social crime.  Mongolia (Mongol uls), 1997. Photograph by Lois Conner This makes it possible to understand why the Mongols of Inner Mongolia have resented and feared all Chinese policies regarding Mongolia, especially progressive policies, all during the years of the Republic. They have felt that the benefit, if any, accruing to Mongols out of policies made in China would be merely incidental and accidental. Every progressive movement in Mongolia under the Republic has resulted in Mongols being driven out of Mongol territory, to make room for Chinese. About ten years ago, during the wars between Feng Yü-hsiang and Chang Tso-lin, some of the more active leaders of the younger Mongols formed a Mongol affiliate of the Kuomintang. The Mongol troops raised under this movement actually took part, eventually, in the Nationalist reunification of China. The Mongols who had led the movement looked forward, to a Kuomintang-guided regional and racial autonomy, under the principles laid down in the San Min Chu I: but even this hope failed, for the Chinese point of view prevailed over that of the Mongols, and the next move within the Kuomintang was one of centralization, leaving no room for an autonomous Mongol Kuomintang. Not only were these leaders—at that time the most important pro-Chinese element among the Mongols—disappointed in not being allowed to apply Kuomintang principles in Mongolia, in affiliation with the Central Party but autonomously independent of it; they saw Chinese encroachment on Mongol lands continuing and even increasing. Colonization of the Mongol regions in Manchuria, for instance, reached its maximum intensity in 1929-30 and the early part of 1931, after Mukden had come to terms with Nanking and hoisted the Nationalist flag. Closer identification of the Inner Mongolian Leagues with the provinces of Manchuria, Jehol, Chahar, Suiyuan and Ninghsia had been one of the first results of Nationalist unification. In 1931, there was published a draft plan for further extending the control of the frontier provinces into the still largely self-governed Mongol tribal regions. A form of hsien government was contemplated which would have practically smothered the remnants of Mongol self-government. Not that the Mongols objected to 'progress,' as such. Their younger leaders were largely republican in sympathy, and opposed to the preservation of antiquated forms of power in the hands of hereditary princes and the Lama Church. What they feared was that 'reorganization,' under a strictly Chinese initiative, and accompanied by colonization, would blot out the Mongols as a racial and national entity, under the sheer weight of Chinese numbers, before they themselves could initiate Mongol reforms based on a reconstruction and modernization of Mongol society. The plan just mentioned was published in the Monggol-on Arban Edur-un Daromal, or Meng-ku Hsün-k'an, the Mongol Ten-Day Journal, printed in both Mongol and Chinese by the Mongol-Tibetan Press in Nanking, an organization closely affiliated with both the Council of Mongol and Tibetan Affairs and the Kuomintang. It appeared, with an irony which could not have been more closely calculated, in a special number celebrating the anniversary of the Chinese Revolution, on the 10 October 1931. This meant that within less than a month after the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, on the 18 September of that year, it was read by every Mongol intellectual and practically every adult literate Mongol. From the point of view of Chinese interests in Mongolia, no more disastrous date could have been chosen.  Mongolia (Mongol uls), 1997. Photograph by Lois Conner The shock of the Japanese invasion galvanized the whole of Inner Mongolia. As an alternative to revolution in Outer Mongolia and the colonization of Inner Mongolia, what would Japan offer? Mongol autonomy under a restored monarchy in Manchuria? There can be no doubt that the Mongol movement which led eventually to the formation of the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Political Council at Bato Khalagha (Pailingmiao) was a direct result of the setting up of Manchoukuo. Indeed, one might as well be frank; there is no point in fogging the issue with polite words. The genesis of the Inner Mongolian autonomy movement was the feeling that united action would make it possible to bargain both Japan and China, to see which would offer the best terms. Since then, however, relations between China and Inner Mongolia have become relatively cordial. It may be worthwhile to attempt a consideration of this improvement from an outright Mongol point of view, rather than a Chinese or Japanese point of view, or according to the tenets of Marxism or any other set system. Among the Mongol leaders the best known name is that of Te Wang, or Prince Demchukdongrob, of West Sunid, in Silingol League, in the north of Chahar province; but the leadership also includes other elements: veterans of the abortive Mongol Kuomintang movement of ten years ago, still younger intellectuals, most of them of non-aristocratic birth, men who have, in the past, led armed rebellions against China, and old-fashioned hereditary princes whose one idea is to calm things down, to hold on to what they have got as long as they can, and to prevent any drastic change of any kind. I have heard Te Wang accused of being ambitious to make himself a 'second Chingghis Khan'; but actually he is more like an Inner Mongolian Roosevelt, attempting to bridle the too impetuous Left with one hand and to whip up the sluggish Right with the other, and so drive the two together on the road of the Center, toward a sober and realistic autonomy, characterized by reforms a good deal in the spirit of Kemalist Turkey. The prevailing note of the Mongol leadership is undoubtedly realistic, with a touch of pessimism. As realists, the Mongols know that it is safer for them, in their weakness, to associate with China than with an expansionist Japan—if they can manage it. They know that so far as they have a quarrel with China, it is with the frontier provinces, which do the actual colonizing of Mongol territory, more than with Nanking. They know moreover that Nanking is primarily concerned with the closer unification of China, and they are willing to gamble on the chance that a little pressure from the side of Mongolia will in the long run do more to promote Nanking's control of these provinces than to impair it. They are willing to gamble also on the chance that the frontier provinces will not undertake troop movements in Mongolia on a really large scale, because of the Japanese situation. Perhaps most of all, however, Japanese policy has favored closer understanding between Nanking and the Mongols. It is true that the establishment of a monarchy in Manchoukuo made a good impression to begin with among Mongol conservatives. The creation of an autonomous Mongol province of Hsing'an, within Manchoukuo, also sent a wave of excitement and half-believing hope westward through Inner Mongolia. Japanese bureaucracy, however, has killed what Japanese statesmanship might have accomplished. The rigidity of the control exercized over the Mongols in Manchoukuo, the fact that the Mongols are not trusted to carry arms unless they are actually enlisted in military service, and the fact that none of the Mongols holding office under Manchoukuo is considered a really capable potential leader by either conservatives or progressives, has convinced them that, so far at least, Mongol autonomy as promoted by Japan is a sham. This, however, does not alter the fact that the Mongols, being realists rather than theorists, by grim necessity, have no intention of fighting to the death against Japan. They know that a Japanese move westward through Inner Mongolia would be only part of a general 'forward policy' in North China; and they have not yet had enough support from China to make them feel like dying for China. In face of a determined Japanese move, they would submit and, for the time being, make the best of it. Since the Mongol question is now in suspense, and the period of direct relations between Mongols and Chinese, uncomplicated by Japanese intervention, has now closed, there could not be a better opportunity to sum up the characteristics of the period of intensified colonization, and its effects both on the Mongol nomad and the Chinese colonist. What, actually, is nomadism, Mongol nomadism? To begin with, there has for centuries been no true nomadism in Mongolia. The Mongols live under a form of society which was established as a compromise between the political requirements of the Manchu empire, and the social and economic traditions of the Mongols themselves. Each Mongol tribal group occupies a territory with well-defined frontiers. Within this territory, all of the land belongs to all of the tribe. People move about freely, because in an arid climate it is not practical to keep animals grazing always on the same fields. Most families in Inner Mongolia have one summer camping-place, to which they return year after year, and one winter place, which is even more permanent, because it is convenient to accumulate a store of fuel for the winter. These two camps are often only a few miles apart. No individual holds any property in land. There being no 'capitalist' monopoly of land, wealth and social advancement depend primarily on the energy and competence of the individual. If he manages his livestock with skill, the natural increase of every year is a clear increase in wealth; he does not have to lay out capital for the purchase of pasture land on which to feed his herds. Nor can the rich man, by asserting private ownership of land, prevent the poor man from grazing his flocks on it. Under such conditions a prince can be poor and ignorant (and often is) and a commoner can be rich and educated.  Mongolia (Mongol uls), 1997. Photograph by Lois Conner In the true Mongol society, as developed by the Mongols themselves, the prince is neither owner of the land nor autocratic master of the tribe. Mongol society created many democratic checks on even the social authority of the prince. It is one of the numerous ironies of the present situation that the excessive authority of the princes is largely a creation of the Chinese Republic. In order to facilitate Chinese colonization, frontier officials 'recognize' in the Mongol princes an authority which according to Mongol standards they ought not to have. Thus Mongol land can be "legally" taken over whenever a prince can be forced or bribed to sign it away in the name of the tribe. In the Mongol society, whether nomadic or semi-nomadic, there is no inherent vice which prevents the development of what we call civilization. In the great days of the Mongol conquests the efficiency of Mongol administration, involving complicated adaptation to varying conditions over an immense empire, was not inferior to Chinese administration in any of the great periods of Chinese history. In engineering and finance they were quickly abreast of the most 'modern' practice of the times. They picked up technique and talent, men and methods and materials, from all over the world known to them with an acquisitiveness never exceeded by 'Western civilization.' The Arabs, another nomad people, within a few years of the first rush of their conquests, were leading the world of their time in mathematics, astronomy, medicine and public administration. In our own time the Mongol learns, given the the opportunity, to handle motor cars and wireless as readily as the Chinese or the Russian does. The herdsman ought not to have to consider himself 'backward' any more than the American rancher consider himself 'inferior' to the American farmer. There is no reason why a herdsman should not read a book, or write one, as well as a farmer. Indeed, I personally do not hesitate to say flatly, although there are no statistics by which I can prove it, that the percentage of literacy is higher in Mongolia at the present time than in China. Setting aside the usual preconception that a settled life is in some mysterious way 'higher' than a nomad life, let us examine the results of colonization in Mongolia. The type of colonization created by the rapid building of railways demanded quantity rather than quality. (This was true in America also.) There was no time to select and train colonists with a view to making the best of the geographical, climatic and economic conditions characteristic of Mongolia. No supply of colonists with capital of their own was available. Consequently the land came under the control of capitalists who could afford to take over large holdings and place tenants on them. The colonists had no experience in handling livestock; consequently 'mixed' farming could not develop rapidly. In order to produce financial results, land had to be farmed even if it was naturally more suitable for grazing than for ploughing. The society that has developed in colonized regions is therefore characterized by a maximum of the bad features of Chinese agricultural economy, and a minimum of the good features of the Mongol economy. Absentee landlordism and excessive crop-rents prevail. Even casual observation makes it plain that standards of literacy, hygiene and self-respect are low as compared with rural China generally. It is no wonder that banditry is everywhere associated, not abnormally but normally, with colonized regions. The first flood of railway-stimulated colonization is now over. It has in fact already reached the point of diminishing returns. It has become obvious that thousands of square miles have been colonized that ought never to have been opened to farming colonization at all. A great deal of Inner Mongolia is semi-arid. The rainfall supports a growth of grass which to a certain extent conserves moisture. The gradual rotting of grass and grass roots produces, over centuries, a thin covering of very fertile soil; but the rainfall is not heavy enough, and the grass not thick enough, to create a deep soil layer. When such land is ploughed, it produces good crops until the wind gets to work at the soil that has been cleared of grass roots and loosened by the plough. The good soil is then blown away, and sand begins to work up from below; or else, by the capillary action of the exposed soil, alkali is drawn up from the subsoil. Nor can the rainfall be supplemented by irrigation. The subsoil water is not sufficient, even where it is not too alkaline. Such districts become totally unproductive, for even if they are abandoned, the old growth of grass will not come back; at least not for many, many years. Human action is rapidly extending the desert areas in Mongolia.  Mongolia (Mongol uls), 1997. Photograph by Lois Conner The low standard of living is also dragging down the once comparatively high standard of the regions colonized before the railway period. Casual observation of the old regions in which Chinese and settled Mongols lived interspersed will bear this out. Everywhere the old comfortable, prosperous buildings are falling into ruin, and the people of the present day live in hovels. Rigorous military action has greatly eased the bandit situation in the last year or two; but the improvement is precarious, for the actual conditions which create banditry are extending. Just at the time when agricultural colonization has failed or run into difficulties (although in places it is still being encouraged, as if failure were not inevitable) new possibilities are becoming evident. As industrialization in China increases, a greater demand for raw materials is being created. The textile industry of Suiyuan is already using Mongol wool. Chinese are beginning to use milk and butter, which formerly were not part of their diet. The demand for leather is increasing. It will not be long before the demand for iron and coal from the new idle reserves of Mongolia becomes practical, instead of theoretical. It would seem that under a diversified economy, with the dead level of a low-grade agriculture improved by the revival of livestock and the development of industry, both the Chinese colonist and the Mongol ought to get a fresh start. As a matter of fact the Mongol, trained from child¬hood to be independent and to do all kinds of different things for himself, to work with leather and felt, to drive a cart and handle a caravan, to be out in all weathers, to find his way over great distances and above all to make his own decisions for himself, promptly and in every kind of circumstance, ought to be well placed in competition with the peasant colonist who has lived in one mud hut all his life, attending without any exercise of initiative to an unchanging routine of planting and harvest, with all his decisions made for him by the landlord and the calendar. Only recently I suggested this to a Mongol friend, but he was pessimistic. He is a leader of the progressive Mongol group in the Bato Khalagha Autonomous Political Council, but he feels that the Mongols have all the breaks against them. 'What you say would seem reasonable to you or me,' he said, 'and of course there are many Chinese who realize that the present forms of colonization are all wrong. The trouble is that the present relation between Chinese and Mongols is already a "going concern"; it has been started, and it is nobody's business to stop it. Besides, when they see what is wrong, they see it as Chinese; nobody has any idea of putting things right for the sake of the Mongols. 'As for the people whom we actually have to deal with—military and provincial officials—they understand absolutely nothing but t'ung hua.[1] We already have competent Mongols who could work with these officials, but they are constantly being antagonized by finding that they cannot work with, only under, the present Chinese policies. It looks as if what is going to happen, in spite of anything we can do, is the driving out of us Mongols by low-grade colonization, after which progressive Chinese will be free to improve things for the colonists who have replaced us.' At this point we would seem to be up against an issue as between sentiment and realism. If the Mongols missed the tide of history, if it is true that they will be unable to survive unless China, or some other country, stops to help them along, then why, after all, should China, hard pressed to hold its own against foreign economic control, Japanese territorial encroachment and internal poverty and lack of resources, turn aside to consider the Mongols, to the possible detriment of the struggle for unification and reconstruction in China? This is an argument which may well have seemed forceful before 1931, when China was working against time to gain control of its own frontiers and forestall foreign aggression. But the fact is that in 1931 the blow did fall. No realist, examining the wreckage caused by that blow, can deny the weaknesses it has revealed in China's position. Faced with one of the major crises in Chinese history, China is compelled to deal with a frontier which, as far as the Mongols are concerned, has not by any means been completely or satisfactorily 'sinized,' assimilated to China. The Mongols are only a minority people, weak in themselves; but they are a minority which has largely been antagonized, and whereas their resentment was formerly impotent, it is now quite possible that somebody else may make use of the Mongols against China. If this is true, then realistic considerations demand that China abandon the effort to coerce the Mongols. The policy indicated by the situation is one of endeavoring to co-operate with the Mongols, on terms as generous as possible, in order to convince them that association with China can be made more advantageous for the Mongols themselves, than association with either Japan or the Soviet Union. The steady improvement in relations between Nanking and the Mongol Autonomous Political Council at Bato Khalagha indicates that this is the policy now being followed. Underlying the present cordiality, however, there is a very serious weakness, and that is the fact that the initiative has been taken primarily by the Mongols themselves. It is the Mongols who have persuaded China that the autonomy movement is not necessarily directed against China. The movement did not arise from Chinese efforts to stimulate a form of autonomy beneficial to both Mongols and Chinese. If the Mongols have taken the lead in effecting this temporary improvement, they may later take the initiative in altering the direction of Mongol nationalism. For, in this major crisis, China is handicapped, almost crippled, by lack of a suitable frontier personnel. The old intermediate groups, Chinese who were half Mongol and Mongols who were half Chinese, have been virtually obliterated by the surge forward of a new Chinese population during the years of railway-stimulated colonization. The cleavage between this new population and the Mongols could hardly be more absolute, for its advance has been characterized throughout by a ruthless over-riding of Mongol interests. There has been, of late years, a vigorous growth of the 'frontier movement' and 'frontier school of thought' in China. This, however, has been guided almost entirely by the theory of t'ung hua—of absorbing the frontier peoples and making Chinese of them, whether they like it or not, or of driving them out, instead of co-operating with them. There is no getting around it. Among the many curious paradoxes of the relation between Chinese and Mongols, none is more ironical than this: that the 'backward' Mongols, the 'primitive nomads' who were not even considered suitable building material for the reconstruction of China, know more about China than the 'civilized' Chinese, the representatives of 'progress,' know about Mongolia. Among the Mongols of Inner Mongolia the number of men who have a good Chinese education is large enough to be considered really significant. The importance of the fact that such men are familiar, through what they read in Chinese, not only with the economic, social and political problems of China but with world affairs, should not be under-estimated. To these must be added the smaller but still important numbers of men who know Russian, Japanese and Tibetan, and the few who know English and other languages. Among Chinese, on the other hand, I do not know of a single official important enough to be influential in forming Government policy, and of very, very few intellectuals writing in the newspapers and more serious publications on frontier affairs, who have a competent knowledge of Mongol, a first-hand knowledge of Mongol life and an understanding, from the Mongol point of view, of Mongol history and current Mongol problems. This applies also, so far as my knowledge goes, to relations with other frontier peoples. How is China to adjust itself, rapidly enough, to changed frontier conditions, and develop the frontier experts that are urgently required? I do not pretend to know; except that, like any man of sense, I can see that a constructive policy must include economic integration as well as political and military mastery.  Mongolia (Mongol uls), 1997. Photograph by Lois Conner Because I cannot pretend to authoritative knowledge, I must end this article on a note of pure speculation. I began with confessing ignorance of Outer Mongolia, and would remind the reader again of this confession. Nevertheless the picture cannot be a complete one if Outer Mongolia is not at least sketched in. Moreover I can say this of my ignorance; it is comparable to that of many of the younger Mongols who know of Outer Mongolia only by theory and hearsay, but are forced to include it in their attempts to find a way out of the labyrinth in which they are involved. It is no use marking Outer Mongolia with the label 'Red—No Exit.' If every other exit is blocked, sooner or later they are going to try the Red exit. It would seem that in Outer Mongolia also it is a sort of crime to be a nomad. Outer Mongolia was, according to the refugees who have left it, an easy land, without any great poverty to drive men to social revolution. Nevertheless the social revolution followed the nationalist revolution in Outer Mongolia, and there is reason to believe, as I have elsewhere argued,[2] that this was inevitable. In Outer Mongolia, as in Manchuria and Inner Mongolia, the old Mongol way of life, on being brought into comparison with new social economic forms, was condemned as 'inferior' and 'backward.' Mongol ideas appear to have been ruthlessly subjugated to alien ideas—deriving, in this instance, from the Soviet Union; although Soviet influence in Outer Mongolia is, apparently, much more indirectly and circumspectly exercized than Japanese control in Manchuria. One cardinal difference, however, distinguishes the changes going on in Outer Mongolia from those imposed on Manchuria and Inner Mongolia; in Outer Mongolia, the voice which decrees 'what is best for the Mongols' may be a Russian voice, but the intention of the changes is a genuinely pro-Mongol intention, and the process of change is in the hands of Mongols, and supported by Mongol troops. Only in Outer Mongolia are both subordinate and high executive positions held by Mongols; only in Outer Mongolia are the schools unmistakeably Mongol; only in Outer Mongolia are the troops Mongol throughout—Russian officers being restricted, by the testimony even of dissatisfied refugees, to training and teaching functions. Where new institutions are introduced, they are manned as fast as possible by Mongols; there is no equivalent of the Chinese introduction of agriculture in Inner Mongolia, which takes the land of the Mongols away from them, or of the Japanese overlordship in Manchurian Mongolia, which reduces the Mongols to the standing of a subject people, to be 'colonially' administered. This may be due to the far-sightedness of Soviet policy, or it may be due merely to the fact that the Soviet Union has not the same oversupply of colonists as China, or the same reserve of unemployed bureaucrats as Japan. That is not the point. The only point of dynamic importance is that in Outer Mongolia alone the introduction of new, alien standards is accompanied by methods which allow of Mongol trust and confidence, a feeling that the future, although new and strange and in some ways terrifying, is yet going to be a Mongol future. About four years ago a wave of new measures for the advancement of the revolution in Outer Mongolia drove several thousand malcontents into Inner Mongolia. I saw hundreds of these refugees at the time, and heard their tales of oppression, of the harsh dictation of measures that to them seemed unreasonable and needless. In the last year I have again seen many of them, and have found a change going on, not as yet universal, but undoubtedly significant. What they say amounts to this: 'The present state of things in Inner Mongolia cannot last. We understand and prefer the old Mongol way of life. We were born free nomads, and free and nomad we intend to live, as long as we can. We do not like this "revolution" business; we do not know what it is all about, and we don't want to. But if it comes to a bitter final choice, of being dragooned by China or dragooned by Japan, we are not going to stand for it. We are going back to Outer Mongolia, to be dragooned by Mongols.' Are we, then, going to see the social 'sinfulness,' the mysterious 'inferiority' of the nomad finally wiped out altogether and replaced by entirely new standards? It may yet be that we shall see a Mongolia in which the Mongols are restored to the control of their own destiny; in which the old nomadic collectivism has evolved into a new, but still Mongol collectivism, and in which the new economic forces of mines and industry, railways and machines, will be manned not by alien conquerors who have reduced the Mongols to an American Indian degradation, but by the free Mongols themselves. It is this possibility which is, to-day, the one valid standard of reference for comparison of the relations between the Mongols and the Soviet Union, the Mongols and China, or the Mongols and Japan. Source:Owen Lattimore, 'On the Wickedness of Being Nomads', T'ien Hsia Monthly 1, no.1 (August 1935): 47-62. Notes:[1] 同化。This expression, much heard along the frontier, is of little comfort to Mongols. It ought to mean 'assimilation,' but in practice it has come to mean 'extermination of the Mongols, to make room for Chinese.' [2] See 'Prince, Priest and Herdsman in Mongolia,' in Pacific Affairs, Vol. VIII, No. 1, March, 1935. |