|

EDITORIAL

No. 19, September 2009

The Heritage of T'ien Hsia, All-Under-Heaven

T'ien Hsia Monthly 天下月刊 first appeared in 1935, at the height of Republican China's 'era of openness'. Based in Shanghai until the editors fled to Hong Kong following the Japanese invasion, the English-language journal T'ien Hsia reflected a positive relationship between the patriotic aspirations of some members of a Western-educated intelligentsia and a generous spirit of cosmopolitanism. Many of the authors featured in the pages of the journal aspired to be an equitable part of the world community; they were close observers of and commentators on recent developments in Euramerican culture while also paying due attention to the major cultural trends of their own world.

In this issue of China Heritage Quarterly we focus on T'ien Hsia Monthly and avail ourselves of that distant era of openness to (re-)introduce our readers to the concept of T'ien Hsia—that of an ecumenical but principled spirit of global engagement that thinking Chinese people aspired to in an earlier age. We will be introducing relevant work from the magazine in future issues of China Heritage Quarterly under a dedicated heading in the menu bar.

That bygone spirit, or at least an aspiration in its favour, is today shared by many members of the global Chinese community. It is also one that enlivens the thinking of those who are positively involved with the burgeoning presence of China on the world stage. In this year of commemoration and sombre reflection (see our March and June issues), the endeavours of the editors and writers of T'ien Hsia Monthly also deserve reconsideration by those interested in the mixed and contested heritages of Chinese culture and thought. By evoking t'ien hsia (and we consciously employ the Wade-Giles spelling used in the Republican era) we invariably will encounter other, and less palatable, dimensions of the work, in particular the revived statist-Confucian concept of tianxia 天下, as well as the ways that the Chinese party-state and thinkers in its thrall attempt to articulate views of a new world order for themselves and others.

In the Features section of this issue we mourn the passing of three figures who have been mentors, an inspiration and friends of those of us related to the China Heritage Project of The Australian National University. We also offer Sun Fo's 孙科 'Forward' from the inaugural issue of T'ien Hsia. The tenor of Sun's remarks resonate with views today that contrast with the virulent strains of fomented Chinese nationalism, something that has been such a public feature of that country's international presence, in particular since March 2008. We also feature an essay by C.L. Hsia 夏晉麟, a noted lawyer and diplomat of the Republican era. An oral history interview by Sang Ye 桑曄 from the upcoming book The Rings of Beijing reflects the life of a man who lived outside the mercurial realm of the ever-changing political fashions of the People's Republic.

In Articles, John Minford discusses how major victory celebrations were marked in ancient times, offering thereby an interesting perspective on the 1 October 2009 mega-event in Tiananmen. Professor Emeritus Anthony Yu has kindly allowed us to publish a memoir of his education with his grandfather and the Beijing-based film-maker Andrea Cavazzuti has given us permission to reproduce the film that he and Carlo Laurenti made on the 1999 grand celebration in Beijing, The Future is Served. We also reprint an article on nomads by Owen Lattimore from the first issue of T'ien Hsia. It offers some historical context to more recent borderland issues in China. Michael Dutton and Deborah Kessler take up the issue of how Australia can be literate in an 'Asian future'. In this section we also include another oral history interview by Sang Ye related to the legacy of the Great Leap Forward of the late 1950s and early 1960s, one that continues to spread heartbreak and sorrow half a century after the event.

In New Scholarship we introduce Critical Han Studies, an undertaking involving numerous scholars who are thinking about, debating and analysing one of the most often used but little studied aspects of the Chinese presence: the Han. The work of scholars like Thomas Mullaney, Mark Elliott and James Leibold, whose writing we feature here, as well as the efforts of their colleagues similarly engaged in Critical Han Studies, adds an important dimension to our appreciation of what tianxia has meant, and what it may mean in this new millennium.

It is a rare pleasure to be able to publish work from a Manchu writer, and we do so in the form of Mark Elliot and Elena Chiu's translation of Jakdan's 扎克丹 preface to selected stories from Pu Songling's Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio 蒲松齡 聊齋志異. We also introduce an upcoming book by Claire Roberts on the friendship between the artist and art historian Huang Binhong 黃賓鴻 and the translator Fou Lei (Fu Lei 傅雷).

I am grateful to Janos Batten for scanning material from T'ien Hsia Monthly and illustrative material from another 1930s magazine, Yuzhou Feng 宇宙風, edited by Lin Yutang 林語堂. Again, Lois Conner has again generously allowed us include some of her wonderful work in this journal, and her images of Mongolia accompany a reprinted essay by Owen Lattimore in Articles. As ever, Jude Shanahan has been understanding, patient and forgiving as she has designed this latest issue of China Heritage Quarterly. The December 2009 issue will be guest edited by Duncan Campbell, and it takes as its focus the heritage of traditional libraries (cangshu lou 藏書樓).

Everything in the World

Geremie R. Barmé

Fig. 1 When the Great Way prevails, the Universe will belong to all.

大道之行也天下為公

In this issue we consider the heritage and legacy of T'ien Hsia Monthly 天下月刊, an English-language publication edited by Shanghai-based writers, educators and thinkers from 1935. Starting from the next issue of China Heritage Quarterly we will include a new section in the menu bar called, simply, 'T'ien Hsia'.[Fig.1] Under this rubric, one that pointedly avoids the increasingly problematic Hanyu Pinyin term Tianxia (which has various connotations related to 'China' and the Chinese world, more of which will be said below), we will reprint essays, reviews and creative works from issues of T'ien Hsia Monthly relevant to the focus of each issue. We will also include in this new section material related to the broader spirit of locally inflected cosmopolitanism favoured by today's open-minded Chinese writers and thinkers, as well as by their non-Chinese interlocutors.

Tianxia wei gong

Fig. 2 The China Critic in Hu Shi’s 胡適 calligraphy. T'ien Hsia Monthly was founded in 1935 with support and funding from the Republican government. Produced under the auspices of the Sun Yat-sen Institute for Advancement of Culture and Education (Zhongshan Wenhua Jiaoyu Guan 中山文化教育館) in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China, T'ien Hsia Monthly was the second journal of its kind produced during the 'Nanjing decade' of 1928 to 1938. The other was The China Critic (Zhongguo pinglun zhoukan 中國評論周刊) founded in 1928.[Fig. 2]

In the Features section we introduce this important publication by reprinting the 'Foreword' written for the inaugural issue by Sun Fo (Sun Ke 孫科), the President of the Legislative Yuan and the son of Sun Yat-sen. Sun Fo was born in Guangzhou in 1891 but grew up in Maui, educated in both classical Chinese and English he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1916, and gained a Master of Science from Columbia University the following year. After a varied professional history related to his father's political enterprise, he became the head of the Legislative Yuan and helped draft the 1930s Republican constitution. He would be a critic of authoritarianism, and his father's aura provided some protection for him, although in his later years he go on to serve the Chiang Kai-shek government-in-exile in Taiwan. He died in 1973.

Following the endless strife between left and right from the 1920s, there was a relative period of exchange, and even civility, in the 1930s and T'ien Hsia is a product not only of the 'lonely isle' (gudao 孤島) era of Shanghai from the late 1930s, but also of the unsettled truce between political enemies that came about during a period of national crisis as the country faced invasion. As Shuang Shen notes of the magazine in the recently published book Cosmopolitan Publics: Anglophone Print Culture in Semi-Colonial Shanghai at that time:

…one encounters a specific form of intersection of cosmopolitanism and nationalism, which was conditioned by the specific context in China in the 1930s. On the one hand, the magazine [T'ien Hsia Monthly] exhibited some distinctly cosmopolitan traits, such as its use of a foreign language, English; the inclusion of the writings of many non-Chinese nationals; and its active attempts to continue to introduce foreign cultures during the war. On the other hand, the magazine also showed a nationalist inclination through activities such as meticulously documenting China's recent cultural achievements and tirelessly translating Chinese literature into English.[1]

One could argue that using the global (and albeit colonial) language of English the editors of the magazine were also sidestepping the rancorous politics of journal publication in Shanghai at the time. They were freeing themselves thereby from the often-vituperative style of polemical exchange that had increasingly infested Chinese public discourse from the 1920s (something that would be exacerbated in the following decades, and which still weighs heavily on mainland Chinese prose today).

Fig. 3 A float made for the 1 October 2009 National Day parade featuring the national flag and sunflowers, a popular symbol in the Mao era. T'ien Hsia was not merely involved in promoting Chinese ideas to an English-language readership, it also offering reviews and articles on international, in particular Euramerican, culture. The magazine's Editor-in-Chief, Wen Yuan-ning (溫源寧), trained in law at Cambridge although before taking up the job in Shanghai he had been a professor of English literature at Peking University. With his broad interests in modernist literature and China's contemporary plight, Wen's obsession with the cosmopolitan spirit is a feature of his editorial work for T'ien Hsia, as well as his contributions.

Today, the concept of Tianxia has connotations that hark back both to autocratic times and into the future, with a meaning that is pregnant with possibility but also deeply unsettling. As we consider the generous spirit of some Republican thinkers and writers, we are reminded of the plangent fate of many of their number and their fellows following the establishment of the People's Republic of China on 1 October 1949, an occasion celebrated by the sixtieth national day parade that will fill Tiananmen Square in Beijing the day after this issue of China Heritage Quarterly is launched.[Fig. 3]

Party Empire

This moment in 2009 is one of official national celebration and commemoration, it is also a moment of achievement that is being observed by interested audiences and anxious people and pondered around the world. The material achievements of the Chinese people in recent decades deserve grand celebration; the behavious of the Communist Party itself, however, is far from being above reproach.

Among the many cultural 'offerings' (xianli 献礼) funded by the state and pro-state business, made by creative and productive individuals and groups in China to mark the occasion, a cinematic extravaganza called Founding of a Nation (Jianguo daye 建国大业) was produced, starring among others Jacky Chan and Jet Li.[2] Commentators remarked that many of the Chinese stars in the film actually hold foreign passports and enjoy international careers. This is perhaps a sign not of disaffection from China as much as an indication that the creative world of China is not limited to some geopolitical territory. From another angle, the name of the film itself is suggestive: the word daye 大业 is one used by founding empires. Indeed, the Chinese title of Frederick Wakeman's important book on the early years of the Qing dynasty, The Great Enterprise (University of California Press, 1985), is Daye.

While the extravaganza occupies the centre of Beijing, there is less to celebrate when we consider the harsh treatment of those who speak out against the egregious behaviour of the Party, or who attempt to offer more nuanced views of the troubled past. A recent example is the banning from the mainland net of the work of the writer Lung Ying-tai in September, shortly before the grand day. It is said that this Taiwan writer who is now based in Hong Kong incurred the wrath of the authorities by publishing her carefully researched and multi-vocal account of 1949 and its divergent histories: Big River, Big Sea—Untold Stories of 1949.[3] The book duly appeared in the open Chinese territory of Hong Kong and Lung promoted yet another book that gained kudos from having been 'Banned in China'.

When looking back at 1949, we would remind readers that the previous issue of China Heritage Quarterly featured two oral history accounts of the momentous events of 1949 and their impact on real lives (see Sang Ye, 'The First National Day', at: http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/features.php?searchterm=018_1949firstnationalday.inc&issue=018). We have also published Dai Qing's account of the 'peaceful liberation of Beiping' in 1948, and the tragic denouement of the public intellectuals who had held out hope for the new regime (see Dai Qing, '1948: How Peaceful was the Liberation of Beiping?' in the June 2008 issue of China Heritage Quarterly, at: http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/features.php?searchterm=014_daiqing.inc&issue=014).

Fig. 4 'Faded National Flag', by Gu Ba. Source: Yuzhou Feng 宇宙風, 1935. On the eve of Dai Qing's own fall from grace in 1989, she published a powerful account of the fate of Chu Anping 儲安平, whose work is relevant to our present discussion of Tianxia. A journalist, editor and publisher, in the late-1940s Chu produced a prestigious and influential magazine, The Observer (Guancha 觀察), which became the forum for the political writings of China's men and women of conscience during the bloody Civil War between the Nationalist forces of the Republican government under Chiang Kai-shek and the Communist armies led by Mao Zedong and Zhu De.[Fig. 4]

In 1947, Chu wrote an article in The Observer in which he reviewed the sorry state of the Nationalist government in the late 1940s. The continued relevance of the writer's observations struck a chord with students and concerned citizens when Dai quoted it in her own work about Chu's life and fate, published in early 1989. Just as so many ideas and views from China's past seem prescient and pressingly relevant today, Chu's remarks made in the late 1940s remain resonant as the Party-state displays its armed strength before the world this year:

In a nation where political parties come to power through armed violence, even if the ruling party has reached an impasse, it will struggle doggedly to maintain its hold on power. This is only natural. If it's a righteous struggle then their effort can be appreciated. However, if they have taken the wrong path and they are merely battling to keep themselves in power then in the end everything they do will be a waste and a criminal act... The Nationalists today have become an organization for the protection of vested interests. We hope that it will pay more attention to the needs of the common people on the lower rungs of society, and not treat them as meaningless...

The Communist Party is presently making a big song and dance about 'democracy'. But if we consider the basic spirit of the Communists we must realize that they are an anti-democratic organization. In terms of the spirit in which they rule there is no difference between them and the Fascists. Both aim at using a strong organization to control people's thinking. The Communists are undoubtedly chanting 'democracy' today in order to unite people to oppose the political monopoly of the Nationalists. But their real aim is their own political monopoly, not democracy. There is a prerequisite in the discussion of democracy, one that cannot be compromised: people must be allowed intellectual freedom. Only when they have such freedom, when they can freely express their ideas, will the spirit of democracy be realized. If only those who believe in Communism are allowed this freedom, then there will be no [real] intellectual freedom or freedom of speech... To be quite frank, our present struggle for freedom under Nationalist rule is really a matter of increasing the degree of our freedom. If the Communists were in power the question would be whether we would have any freedom at all.[4]

After 1949, following a false dawn, Chu Anping, like so many others, tried to accommodate himself to a new and increasingly repressive government. His remarkable journal was closed, but it was soon re-launched as The New Observer (Xin Guancha 新觀察), it was little more than an anodyne outlet for the Party's propaganda effort. For a time it seemed that Chu too would conform and learn to swallow the nostrums of the day. He became a publishing bureaucrat and he was eventually given a prestigious position with Guangming Daily 光明日報, a leading newspaper avowedly aimed at the intelligentsia intellectuals as well as being the organ for the Chinese Democratic League.

In 1956, the Party launched a campaign in which it encouraged its critics and malcontents to speak out, or as the slogan put it to 'let a hundred flowers bloom and a hundred schools of thought contend' (baihua qifang, baijia zhengming 百家齊放,百家爭鳴, the so-called Hundred Flowers Campaign). It was a nationwide movement during which people were welcomed to 'help the Party correct its errors'. After some months of 'blooming and contending', in the spring of 1957, under Chu's tutelage, Guangming Daily attempted to assert its independence by setting up a network of correspondents outside Beijing. For a short time, the paper itself became something of a forum for dissenting views. On 1 June that year, encouraged himself to speak out against the egregious failings of the Communist Party, Chu wrote a contribution to the 'speaking out' entitled 'The Party Empire' (dang tianxia 黨天下), with the subtitle 'Some advice to Chairman Mao and Premier Zhou Enlai'. Under Chiang Kai-shek the concept of 'Tianxia' had been perverted to serve the interests of what Communist critics like Chen Boda 陳伯達 would sum up as 'the Chiang family dynasty' (Jiangjia wangchao 蔣家王朝). After remarking on the way in which the Communist Party had in turn insinuated itself into every aspect of public and private life, Chu offered the following:

The crux of the problem lies with what I call the 'Party Empire'. In my opinion the Party's control of the state does not give it the right to treat the nation as its personal property. Everyone supports the Party, but no one has forgotten that they [themselves] are the true masters of the nation. The main concern of a political party that takes power should be the realization of its ideals and implementation of its policies. Certainly, a party needs to remain strong so that it can do this and maintain stability; it needs control over some crucial sectors of the state mechanism. This is quite natural. However, to put a Party boss into every unit and organization throughout the nation, in every bureau and group, and to make everything, no matter large or small, contingent on the reaction of the Party man, to force people to rely on the Party man's nod of approval to do anything, is surely somewhat extreme, isn't it?...

Soon thereafter, Mao turned the campaign for free speech into a witch-hunt for dissident opinion. Chu and many others connected with the Guangming Daily were labelled as 'Rightists' and denounced as conspirators who had made a 'frenzied attack on the Party and planned to turn China into a bourgeois country'. Most of them were persuaded to 'recognize' their errors and undertake self-criticisms. After many years in obscurity, Chu Anping disappeared mysteriously in 1966.

A Whole Tianxia of Hurt Feelings

Great economic achievement and enhanced international standing put to one side, there are dimensions of China's 'coupling with the world' (yu shijie jiegui 与世界接轨) since the 1990s that has well suited a polity led by a secretive and fearful élite burdened with a residual Cold War mindset. Taking umbrage for slights, real and imagined; high dudgeon used as a theatrical ploy against nations around the world; orchestrated paranoia and poisonous rancour on the net and media—these are all aspects of China's popular engagement with the global community. Such a narrow and testy view of 'Tianxia' often leaves scant room for a relaxed and mature international presence, and too readily poisons potential amity. While the world may be ready for a China risen, it is easily unsettled by unnecessary pique and hyperbolic eruptions. This policed approach to Tianxia is heavily reminiscent of the old Cultural Revolution-era slogan: 'Hold the motherland in one's breast while casting one's gaze over the world' (xionghuai zuguo, fangyan shijie 胸怀祖国,放眼世界), which was an expression of politically calibrated patriotic defiance. Of course, in the Deng Xiaoping years the old Maoist formula was recalibrated to become 'look out to the world, consider the future' (fangyan shijie, fangyan weilai 放眼世界, 放眼未来). However, when the country and its people are more in the world and part of the world than ever before, perhaps it is time for such slippery sloganising to be reconsidered.

The Party-state's use of nationalism and the imposition of its view, its historical perspective and its own mission on the nation, and those who have befriended it, create a paradoxical situation. As C.L Hsia noted in the first issue of T'ien Hsia Monthly (reproduced in full in the Features section of this issue):

One vice of Nationalism is jingoism. In a nationalist age, Pan-nationalism and its sturdier brother irredentism can admirably serve the purpose of Imperialism. In the name of Nationalism citizens have been called to take up arms to secure any territory to which their nationality has ever had any sort of claim or on which their national flag has ever been hoisted, and to wreak vengeance on any land on which their fellow nationals have suffered in person or purse. Such misplaced nationalism looks forward to the ultimate extension of one's 'mission' at the expense of the missions of all other peoples.

When Nationalism proceeds unchecked it becomes intolerant toward internal criticism or toward minorities within the nation which leads to either oppression or ugly domestic strife.

In recent years in China there has been renewed talk of a Tianxia, in particular in the context of a new 'Tianxia System' for international politics, one that is inclusive and articulated through a 'magnanimous social grammar'. This approach to a new age for the international order has been articulated by the Beijing-based international relations thinker Zhao Tingyang in a language that has found a ready reception in China. As William Callahan remarks in an insightful discussion of Zhao's work:

In China's all-inclusive Tianxia system distinctions between inside and outside, and even friends and enemies are more relative that absolute. While the west, according to Zhao, starkly divides the world according to racial distinctions, Chinese thought unites it according to an ethical logic that is cultural. The goal of the Tianxia system is 'transformation' (hua) that changes the self and the Other, normatively ordering 'chaos' by transforming the 'many' into 'the one'. While Carl Schmitt defines politics as the practice of publicly distinguishing between enemies and friends, Zhao tells us that 'Tianxia theory is a theory for "transforming enemies into friends', where 'transformation' seeks to attract people rather than conquer them'.[5]

Fig. 5 T'ien Hsia Monthly, frontispiece. Callahan's study of Zhao's theory points out is flaws, both in its cavalier use of classical Chinese thought and modern international social science theory. However, he also persuasively argues that China's thinkers are aware that mere economic heft and diplomatic power are not enough for one of the grand civilisations of human history, one that is enjoying an unprecedented growth and international influence. They feel that it is necessary also to generate new ideas about human society and global organisation, even to offer 'Chinese solutions' to world problems. Zhao Tingyang is only one of many who would now 'look out to the world' (fangyan shijie).[Fig. 5]

The Party's Place in Tianxia

Theories about China's incorporation in the new world order abound: how will it play a role as a responsible stakeholder, or equal partner and participant? Will the global rules of engagement by necessity (and due to sheer economic heft) be rewritten? Will the post-WWII protocols fall into desuetude and be replaced by some new multi-lateral, multi-centred international system? Can Chinese thinkers, constrained as they are by the realities of the Party's autocratic behaviour and skittish paranoia, really be free to debate and argue for a more open and daring involvement with the world? Will the talk of new ideas in China be constantly constrained by the priorities of an unelected and shadowy elite, and so on.

The Party-state leaders of the People's Republic are somewhat more cautious, at least in their public statements, about what China can expect from the world, and what the world can expect from China. After all, the Party-empire remains fearful of much of its own history. It shies from a truthful accounting in public of its conflicting legacies and its territorial claims, and rigorously persecutes those who go against manufactured 'mainstream opinion'. It has difficulty confronting rationally the reasons why its borderland populations are restive, it continues to police dissenting opinion and is ever-vigilant about those who would challenge its role, its vehement rhetoric or even deride its unsteady gait on the global stage. Yet, for all this uncertainty, and regardless of the fact that the present leaders will in two years give way to new internally appointed corporate men, they are anxious to make a show of China being able to impress the world with a certain 'soft power' charisma. Perhaps there are those who even believe that Party-approved or a normative 'Chineseness' can somehow cause trading partners, governments and wary publics to overlook the harsh realities of 'the Party-empire', or at least to be cowed by its egregious expression even when it affronts their own sovereignty. This international domestication of responses to China's political habitus has increasingly unsettling ramifications.

On 17 July 2009, at the Eleventh Meeting of Chinese Ambassadors in Beijing, the state president Hu Jintao made a speech in which, among other things, he emphasized the need for the country to achieve 'four strengths' (si li 四力). That is to say, China's diplomatic effort must concentrate to ensure that the nation:

Politically enjoys enhanced influence (zhengzhishang geng you yingxiangli 政治上更有影响力);

Economically enjoys enhanced competitiveness (jingjishang geng you jingzhengli 经济上更有竞争力);

Promotes an enhanced national charisma (xingxiangshang geng you qinheli 形象上更有亲和力); and,

Ethically/morally has enhanced appeal (daoyishang geng you ganzhaoli 道义上更有感召力).

Hu emphasized that China should not make enemies for itself, or take an aggressive stance (buyao shu di, bu yao chuji 不要树敌,不要出击) in its diplomatic engagement, and that 'diplomacy will play a key role in helping us achieve the goals of reform, development and stability crucial to tackling the financial crisis and maintaining rapid economic development.'

On 9 August 2009, in an interview with Xinhua News Agency, China's Foreign Mininster Yang Jiechi 杨洁篪remarked that in the last few years Chinese foreign policy had moved from ensuring the nation's international survival to that of pursuing development, the underlying thinking is no longer about emphasizing difference (li yi 立异), but rather in pursing similarities (qiu tong 求同). China needs to work with other nations and ensure positive relations. Similarly, in an interview published on 1 June 2009, Wu Jianmin 吴建民 (former Chinese ambassador to The Netherlands and France, head of the News Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and presently the President of the Foreign Affairs Institute in Beijing) remarked that cooperation was the dominant thinking among the country's leaders. That was not to deny that there will be struggles (douzheng 斗争), even in those instances the emphasis is on 'struggle but not breaking off [ties]' (dou er bu po 斗而不破). These 'struggles' are taken up with the aim of achieving better cooperation, not for the sake of generating diplomatic rifts. Some, he said, criticise the Party-state for being diplomatically too soft; given the fact that China has such obvious strengths it should be more confident about getting angry (fa piqi 发脾气) when the need arises, and banging the table (pai zhuozi 拍桌子) when the situation calls for it. But, Wu argued, what's the use of such behaviour? And he said in effect, If we act tough now that we are only a nation in which the average annual income is US$3000 what will we be like when we are making US$20,000 per capita? The West has spoken of China's re-emergence in terms of the 'rise of a great power' (daguo jueqi 大国崛起), but it's a trap, that's because the accepted view is rising great powers always hold sway over others and dominate. China cannot pursue such a strategy. China will be on the rise for many years to come. As Deng Xiaoping observed, we have to 'hide our capabilities and bide our time' for at least one hundred years.[6]

Those today who would re-imagine and retro engineer the concept of Tianxia for a revivified China must engage in mental acrobatics of a kind familiar to connoisseurs of Maoist era dialectics. China is a party-state that employs coercion, education, nationalism and heedless economic growth to maintain a 'harmonious society'. Its moral authority is based on economic performance and a rigid national cohesion backed up by extraordinary military might and vituperative propaganda. The rule of virtue, social order and civilising grace that were all supposed to be the hallmarks of All-Under-Heaven in the past are glaringly absent. Well may Hu Jintao and his fellows call for enhance moral suasion and cultural charisma as China features more prominently as a global power. And the line is now for the world to better appreciate 'China's story' (Zhongguode gushi 中国的故事), sadly it is a story that the Party-state assumes can have the one narrative thread, a coherent dramatic arc and carefully selected and worthy dramatis personae. They might want a monologue, but who wants to listen?

The solemn undertakings by the Communist Party's leaders, propagandists and fellow travellers to usher in an era of democratic freedom for China were made over sixty years ago in the face of senescent Nationalist rule, and the family-state of Chiang Kai-shek's increasing autocracy. Chu Anping was prescient in his warnings against accepting the Communist Party's promises at face value; many of his fellow public intellectuals were more kindly disposed, and desperate to believe, in a brighter future under a new party. But, as the Party would eventually claim: one historical decision to support their rise to power gave them a mandate, for the weal and the bane of the Chinese nation, to rule the Chinese Tianxia henceforth. The Party-state also arrogates unto itself the right to determine appropriate Chineseness, what constitutes the Chinese tradition, acceptable history, and permissible interpretations of the vast and complex heritage, material as well as intangible, that those today inherit.

An Age of Openness and its Legacies

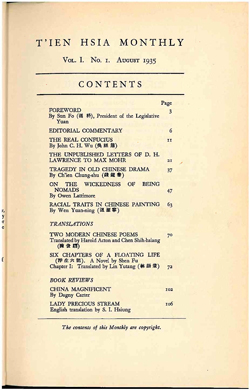

Fig. 6 T'ien Hsia Monthly, contents. Over the past decades scholarly work on Republican China (1912-49) has brought into relief the many rich developments in a era that pre-dates by decades many things that are more readily associated with mainland China's post-1978 Open Door and Reform regime: positive engagement with international bodies, new institutions as well as institutional reform, improved governance and various nation building initiatives, economic performance and cultural efflorescence, among others. This work on the Republic is neatly digested in Frank Dikötter's The Age of Openness: China Before Mao (California University Press, 2008). Dikötter's corrective view of the Republican era is timely and important. To an extent the present issue of China Heritage Quarterly engages with that undertaking and attempts, in a small way, to bring the conversation of the past into the context of the present. But, we should also note that certain salient features of post-socialist Chinese attitudes, behaviour and institutional practice that are less felicitous also have roots that reach at least as far back as the formative years of the Republic.[Fig. 6]

The extremist rhetoric of revolution, for example, was a major feature of the early Republic. The ready resort to outrage, vituperation and denunciation are hardly of recent origin. The verbal violence of that earlier era and the evolution of a public culture that fed on and into consumer vitriol formed the basis for the later militarist language of the Communist revolution, as well as of the hyperbole of contemporary Chinese media hype. Similarly, the use of imperial and autocratic symbols and habits endemic in political life and practice helped transform traditional modalities into the political landscape of Chinese modernity. The 'partification' (danghua 黨化) of the nation struck root in the 1920s and 30s, and early on caused disaffection among many thinking people. The constant civic campaigns and militarisation of the society of the Republican era would develop into a national biorhythm under the Communists; they were building on a heritage evolved over many years rather than merely importing something ready-made from the Soviet Union of the 1950s. Indeed, the Party-state of the Nationalist era presaged much that would continue after 1949. It is this legacy too that provides part of the bedrock of communication between the estranged parts of China even today.

The consideration of T'ien Hsia and its Döppelganger, or sinister twin, Tianxia is important in the era of an economically vibrant China. In 2009, Australia experienced the complications of a relationship with a politically narrow and authoritarian polity that is economically avaricious. In developing an approach that balances liberal values with economic value, issues related to China's own maturation on the global scene come to the forefront. The aspirations and hopes of thinking people today lead often to the ideas and ideals of the past—in particular of the May Fourth Era and the late 1940s, discussed previously.

Fig. 7 Sun Yat-sen's Tomb, Zhongshan Ling, Nanjing. Photo: the author. It is on this sombre note that the year of anniversaries and commemorations draws to an end. All too soon another year of uncomfortable celebration will confront the Chinese world. The year 2011 marks the centenary of the Xinhai Revolution 辛亥革命 that saw the abdication of the last dynastic house in Chinese history and the birth of the Republic of China. That Republic promised national strength, democracy and freedom. While its promise would soon be betrayed, the heritage of those who rejected autocracy and demanded a role in their own political future will be celebrated in some parts of the Chinese world not only as a closed chapter of history but as the precursor of a modern civil joining with the world.

The quotation at the start of this issue features Sun Yat-sen's famous hope—Tianxia wei gong.[Fig.7] It is worth recalling that talk of the Great Way or Way of Heaven has often led Chinese thinkers to ponder, and despair. In conclusion, we should recall the early historian Sima Qian's agonised reflection from his 'Biography of Boyi and Shuqi', recorded in his Records of the Grand Historian:

Some people say, 'The Way of Heaven [tiandao 天道] is fair and without prejudice. It is always on the side of the good man.' Yet as for Boyi and Shuqi [who starved to death in the mountains], were they not good men?...Is that the kind of reward that Heaven bestows on the good? Robber Zhi killed innocent people daily…and yet he lived to a ripe old age. What virtue did he posses to bring him such benefits?...These thoughts vex me greatly! The so-called Way of Heaven, does it exist or not?[7]

Notes:

[1] Shuang Shen, Cosmopolitan Publics: Anglophone Print Culture in Semi-Colonial Shanghai, Rutgers University Press, 2009, pp.62-63.

[2] See: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/the-thoughts-of-chairman-mao-starring-jackie-chan-and-jet-li-1783408.html.

[3] See 龍應台, 《大江大海:一九四九》, 香港:天地圖書有限公司, and www.cosmosbooks.com.hk for details.

[4] From Dai Qing, Chu Anping and 'the Party Empire', translated in Barmé and Linda Jaivin, eds, New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese Rebel Voices, New York: Times Books, 1992, pp.360-361.

[5] William A. Callahan, 'Chinese Visions of World Order: Post-hegemonic or a New Hegemony?', in International Studies Review (2008) 10, pp.749-61, at p.752.]

[6] 'Wu Jianmin shu Zhongguo waijiao 60 nian bianhua: taoguang yanghui reng yao guan 100 nian' 吴建民述中国外交60年变化:韬光养晦仍要管100年, at: http://www.china.com.cn/news/local/2009-06/01/content_17862291.htm/

[7] Quoted in Limited Views: Essays on Ideas and Letters by Qian Zhongshu, Selected and Translated by Ronald Egan, Cambridge, Ma.: Harvard University Asia Center 1998, p.311.

|