|

||||||||

|

ARTICLES嘉 The Triumph: A Heritage of Sortsby John MinfordThe following material is taken from a new translation, with commentary, of the Book of Change. This short extract can fruitfully be read in tandem with Mary Beard's The Roman Triumph, Harvard, 2007, where the scholar of classics argues that the Triumph was a central feature of Roman culture. Highly ritualised celebrations remain important means for expressing military prowess and political vigour in the contemporary world, something evident in Tiananmen Square on 1 October 2009.—The Editor. Ceremonial triumphs, of a gruesome nature, have a long history in China. References can be found in the most famous of all the Confucian Classics, the ?eighth-century BCE Book of Change (Yi Jing 易經). The text used here is that of the silk manuscript unearthed in 1973 at Mawangdui, near Changsha. The manuscript, which was buried in the tomb of the Marquis of Dai, Chancellor of Changsha, can be dated with some precision to the beginning of the second century BCE. (See Zhang Liwen 張立文, Boshu Zhouyi zhuyi 帛書周易注譯, Zhongzhou guji, 2008, p.346.) Hexagram XXX

Yang in Top Place Commentary: Compare this with a bronze inscription (the Duo You Ding Cauldron discovered in 1980) probably from the reign of King Li (859-842), in which 235 men have their heads cut off, 23 prisoners are shackled and held for interrogation, 117 Rong-barbarian carts are captured; and with another inscription probably from the slightly later reign of King Xuan (827-782), when the 'illustrious Earl Ji' attacked the Xianyun, cut off 500 heads, shackled 50 prisoners...—from Edward Shaughnessy, The Composition of the Zhou Yi (1983), pp.41-2, and p.298, n.49. Compare also the contemporary classic, The Book of Songs (Shi Jing 詩經): Song 168, verse 6 出車 'Out Go the Chariots' Orioles sing in harmony. 采蘩祁祁 執訊獲醜 薄言還歸 赫赫南仲 獫狁于夷 In his translation of The Book of Poetry Legge calls this song 'An Ode of Congratulation on the Return of the Troops from the Expedition against the Xianyun'. Prisoners are being interrogated, or as Legge speculates 'put to torture', before their ritual beheading (p.264). Song 178, verse 4 采芑 'Gathering Millet' How foolish were those savage tribes 蠢爾蠻荊 Again, Legge (p.284) describes this song as follows: 'Celebrating Fangshu, and his successful conduct of a grand expedition against the tribes of the South'. Fangshu's victory was the occasion for a great military triumph. But the most famous triumph recorded in bronze inscriptions is the one celebrating the success of Yu's campaign against Devil Territory, on the Da Yu Ding and Xiao Yu Ding cauldrons.

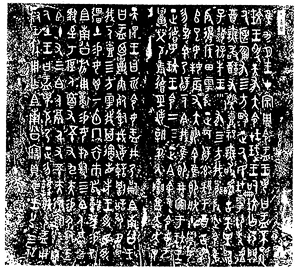

In the twenty-third year of his reign (981 BCE), King Kang of Zhou 周康王 appointed a man named Yu 盂, the grandson of one Nangong Kuo 南宮括, one of the high ministers mentioned by the Duke of Zhou as serving both Kings Wen and Wu, to act as an overseer of the Supervisors of the Military [sirong 司戎]. Yu commemorated this appointment by casting a great ding 鼎 cauldron, now referred to as the Da Yu Ding [大盂鼎 the Great Cauldron of Yu], one of the most impressive bronzes of the entire period.  Two years later, Yu cast another bronze cauldron, known as the Xiao Yu Ding [小盂鼎 the Lesser Cauldron of Yu], the inscription on which describes in grand detail the ceremony held to celebrate his decisive military victory won by Yu over a people known as the Guifang 鬼方 [Devil Territory], probably living in the Ordos area of northern Shaanxi and Shanxi. Only portions of a single rubbing of the lengthy inscription of this vessel still survive (the vessel itself, probably discovered in the 1840s, was lost shortly thereafter in the course of the Taiping Rebellion), but it deserves extensive quotation both for the light it sheds on the Zhou expansion late in King Kang's reign, and also as an excellent example of the sort of military and court ceremonial narrative found in some bronze inscriptions.

Herrlee Glessner Creel's description of this ceremonial triumph is an evocative one, and his footnote particularly gruesome and enlightening.

|