|

ARTICLES

Ming Fever | China Heritage Quarterly

Ming Fever:

The Present’s Past as the People’s Republic Turns Sixty

Michael Szonyi

Harvard University, Cambridge*

Fig. 1 Those Happenings of the Ming Dynasty.

In the summer of 2007, while collecting research materials in rural south China, I was struck by how often historical topics came up in conversation with the villagers I was interviewing. Evening interviews had to be scheduled around the nightly television broadcast of a miniseries about the founder of the Ming dynasty, the Hongwu 洪武 emperor (Zhu Yuanzhang 朱元璋, 1328-98, r.1368-98) Next morning, everybody would be talking about the previous night’s episode. Browsing the main Xinhua Bookstore in Beijing a few weeks later, I was also struck that the biggest bestseller, the book with the most prominent display, was not a guide to success in business or how to prepare for the TOEFL, but a work of history. The book was the first volume of a series called Those Happenings of the Ming Dynasty (Mingchao naxie shi’er 明朝那些事兒), and over the next few months, I often noticed people, young and old, on airplanes and long-distance buses, in university cafeterias and on park benches, engrossed in reading books in this series. China had caught ‘Ming fever’ (Ming re 明熱).[Fig.1]

The People’s Republic (PRC) has always had a complex and fraught relationship with China’s history. Mao Zedong read historical works voraciously and was fond of quoting from them and employing historical allusions. But he also launched campaigns like the Anti-Four-Olds movement (po si jiu 破四舊), seeking to destroy the influence of the past as well as its material legacies in the hope of producing a blank slate on which to build a utopian future. Like other regimes in China and elsewhere, the PRC government has frequently used historical narratives to construct national identity and to legitimate policies. One has only to think of official accounts of the history of Taiwan or Tibet. The current Ming fever suggests that the past is still very much part of life in the present in China. But the driving force behind this use of the past is popular consumption rather than state production. In this essay I use the recent Ming fever as a way of exploring the uses and power of history in the People’s Republic. Rather than assessing the accuracy of any particular historical narrative or representation, my interest is in how and why such narratives are seen as relevant to present day concerns.

I do not wish to over-state the significance of the contemporary interest in history in general or the Ming period (1368-1644) in particular. In China today many other issues matter to people more than stories about history—economic worries, political instability and social turmoil—and most people take less interest in the distant past than they have pride in recent accomplishments. But the Ming fever is nonetheless a social phenomenon that can perhaps tell us something important about the PRC today and even tomorrow. I will argue that the Ming fascinates people today both as a parallel to their own world and as the perceived origin of key elements of it. The Ming bears witness that an economically vibrant, globally engaged China can still be truly Chinese, while the fall of the Ming sounds a warning about official corruption and elite profligacy in the present. But the Ming analogy also permits reflection on the sensitive issues of a multi-ethnic nation. Ming history, therefore, serves in China today both to legitimize the present and as a safe tool by which to criticize aspects of a present in which open discussion of politically sensitive themes remains constrained. Popular understandings of history can serve as a window into how Chinese people think about themselves, their society and their prospects.

A Chronology of the Ming fever

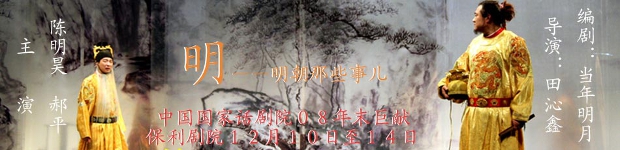

Fig 2 Online Ming pundit Dangnian Mingyue.

The first symptoms of what would come to be called the ‘Ming fever’ or fad appeared in 2005, the six hundredth anniversary of the voyages of Zheng He 鄭和 (1371-1433), the eunuch who led a series of massive official naval missions throughout southeast Asia, as far as the Middle East and the west coast of Africa. The anniversary inspired a host of commemorations, culminating in the State Council declaring 11 July to be ‘China National Maritime Day’ (Zhongguo hanghai ri 中國航海日). There were state sponsored conferences and exhibitions, historical reconstructions, and a high-budget television drama about the exploits of the fifteenth century traveler. The Nanjing shipyards where Zheng He’s boats were built have been developed as a park and museum. (See, for example, China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 2, June 2005).

Several other television miniseries aired in the next year to great acclaim, including ‘The Great Ming Dynasty in 1566: the Jiajing 嘉靖 Emperor and Hai Rui 海瑞’ (Da Ming wangchao 1566—Jiajing yu Hai Rui 大明王朝1566—嘉靖與海瑞), a retelling of the famous story of a dynasty under threat and of the minister whose loyalty and honesty were his undoing. Popular interest in the Ming dynasty took other forms as well. In 2007, the distinguished Renmin (People’s) University historian Mao Peiqi 毛佩琦 gave a well-received series of seventeen lectures about the Ming era on the television program Lecture Room (Baijia jiangtan 百家講壇). The show has been a sleeper hit for CCTV since it first aired in 2001. Almost cancelled due to low initial ratings, it has become one of the most popular shows on television, creating in the process several academic media stars.

Fig.3 Daming wangchao poster.

Fig.4 The Ming historian Mao Peiqi.

Publication of popular books on the Ming has also been booming, including biographies of emperors and prominent ministers, fictionalized accounts of the fall of the dynasty, and several collections of lectures by prominent scholars. Of the more than fifteen thousand books of history published in the PRC in 2006, the largest number reportedly dealt with the Ming.[1] Ray Huang’s 1587—A Year of No Significance, first published in Chinese in 1982, has been re-issued in a new and expensive commemorative edition. A Chinese translation of Gavin Menzies’ 1421: The Year China Discovered America appeared in 2005. Although Menzies’ claims that Zheng He’s fleets went as far as Australia and California have been almost universally dismissed by professional historians both in China and the West, the book aroused considerable popular interest.

The newest site of popular interest in the Ming is the Internet. Here the central figure is Shi Yue 石悅 , a young official in China’s Customs Service who is better known by his internet pseudonym, Bright Moon of Yesteryear (Dangnian Mingyue 當年明月). The name is a reference to continuities over time; though everything changes, the moon is as bright as it was long ago. In March 2006, Dangnian began to post tales about the Ming dynasty on the popular BBS site Tianya 天涯, under the subject line ‘Those Happenings of the Ming’. The posts generated huge numbers of hits and a considerable uproar. Netizens divided into two camps. Dangnian’s admirers labelled themselves ‘Ming fans’ (Ming fan 明矾) and celebrated his combination of erudition and flair. Others launched attacks on the BBS, disagreeing with Dangnian’s historical views or accusing him of artificially inflating his numbers of hits. Some posted graphic pictures of traffic accident victims on the comments section, hoping to dissuade readers. Some launched screen-flooding or spamming to interfere with the operations of the website. Accusations of ‘Internet terrorism’ flew back and forth. There were calls for the Tianya moderators to step down.[3]

Recognizing the interest, publishers quickly bought the rights to Dangnian’s work. The first volume—the one that I saw in the Beijing Xinhua Bookstore—appeared in late 2006 to great acclaim. As one effusive reviewer put it, Dangnian’s book was written with ‘the patience of a Swiss watchmaker, the attention to detail of a German engineer, the romanticism of a French vintner, and humor of an American movie star.’[3] Six more volumes have appeared since, with total sales reportedly reaching two million, a remarkable figure given that the content of the earlier books can easily be downloaded for free. Dangnian is now said to be the bestselling author of history in decades, and has undergone a remarkable transformation from a retiring and sometimes awkward blogger to a polished celebrity. His stage adaptation of the King Lear story, titled ‘Ming’, premiered at the National Theater in October 2008.

At some point, all of this public interest in a long lost dynasty was given the label ‘Ming fever’. Having been labelled the phenomenon became the subject of study and analysis. Stories about Ming fever began to appear in the media in 2007 with headlines such as, ‘Why is the Ming so hot?’, ‘How did the Ming dynasty become a tasty snack?’ Even the journal Contemporary Nursing offered ‘A psychological interpretation of the Ming history fever’. It truly seemed, as a popular catchphrase ran, that ‘this year is the Year of Ming’ (Jinnian shi Mingnian 今年是明年) (The term ‘Year of Ming’ can also be read ‘Next Year’, so the phrase is a pun that also means ‘This Year is Next Year’). By mid-2009, the marketers had taken over the idea, and copies of Happenings of the Ming Dynasty were being sold with a sticker that read, ‘Re-heat the 2008 Ming fever’.

Ming Fever: Parallels and Origins

Fig.5 ‘Reheat the 2008 Ming Fever’.

The Ming is not the only historical period about which there has been a fever (re 熱) or surge of popular interest in the last few years. ‘National Studies fever’ (Guoxue 國學熱) centers on contemporary interpretations of classical texts. The ‘Yu Dan fever’ (Guoxue 于丹熱) celebrates a charismatic academic whose popularized interpretations of Confucius were launched on the same television show as Mao Peiqi’s talks on the Ming, CCTV’s Lecture Room. High Qing fever and Late Qing fever explains several television miniseries. A fever for world history has been most evident in the 2006 CCTV documentary ‘Rise of the Great Nations’ (Daguo jueqi 大國崛起), which implicitly compared China today to the great empires of the past. What is the character of these fevers? What is it that makes some historical periods ‘feverish’? More broadly, what explains these waves of general interest in history and historical topics in contemporary China?

The content of the new history shifts away from the explanatory frameworks that dominated historical writing in the early years of the People’s Republic. Class struggle and historical materialism are no longer the key driving forces of history. Instead, there is a new focus on the role of the individual in making history. But earlier black-and-white caricatures of historical actors are rejected in favour of new efforts to recognize their complexity. This means reassessing their historical significance. The effort to show more nuanced personalities extends even to more sensitive recent history, such as the sympathetic portrayal of a Japanese soldier in ‘City of Life and Death’ (南京!南京!), a recent film about the Nanjing massacre.

These fevers have all been multi-media phenomena, taking shape in books; on the Internet; on electronic bulletin boards and sometimes also as computer games, and on television in the form of televised lectures and historical miniseries. Matthias Niedenführ notes that television miniseries or historical soap operas have effectively created nationwide events by virtue of their simultaneous daily broadcasts. These events encourage the citizenry to reflect on and talk about national history.[4]

Clearly, the fevers are driven in part by the market and the commodification of history. Without a certain critical mass of middle-class consumers of history who purchase books and DVDs, use the Internet and watch advertisements there would be no historical fever. The influence of market considerations is most evident in big budget television miniseries. In publishing, too, the popularity of Dangnian’s work quickly spawned a host of imitators, and within a year of Happenings of the Ming Dynasty hitting bookstore shelves it was joined by Happenings of the Han Dynasty, Happenings of the Tang Dynasty, and so on. Several of the recent Ming-related books are written by academic historians seeking a broader market.

In some cases the Chinese state has had a role. One example is the production of the miniseries, ‘The Great Ming Dynasty in 1566’. It seems that in 2003, during an inspection tour of Hainan, Wu Guanzheng 吳官正, at the time a Politburo Standing Committee member and Secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, the body within the Chinese Communist Party charged with maintaining internal party discipline, visited the home of Hai Rui, the famously virtuous Ming official. He asked senior provincial officials why they were not doing a better job of popularizing Hai Rui as part of an on-going anti-corruption campaign. Production of the miniseries began not long after, with Hainan party leaders giving strong backing and a unit of the Discipline Inspection Commission named as co-producer of the show.[5] (This is of course not the first time Hai Rui’s history has been politically manipulated. It was a play about Hai Rui, interpreted as an allegorical critique of Mao Zedong, that launched the first salvoes of the Cultural Revolution.)

Fig.6 Politburo member Wu Guanzheng.

But the Internet limits the capacity of both the government and the formal media to control the interpretation of history. All these historical fevers have generated considerable public debate. The debates, often highly impassioned, play out in private conversation, in the press, and above all on the Internet. Their subjects can be broadly divided into three issues. First, there are debates about actual historical judgments. For example, as part of the late Qing fever, some nineteenth-century figures formerly portrayed as reactionaries, such as Li Hongzhang 李鴻章 and the Empress Dowager 慈禧太后, have been reassessed and even re-labeled as progressives. Not everyone agrees with these more positive assessments. The sympathetic portrayal of the Japanese soldier in ‘City of Life and Death’, though he was only a fictional character, led to death threats against the film’s director. Second, there are debates about form and genre, about the validity of different types of historical representation. For example, there has been much discussion about how to situate Those Happenings of the Ming Dynasty in the traditional schema of official versus non-standard histories (yeshi 野史), and of history versus historical fiction.

Third, there are debates about the links and parallels between historical periods and contemporary China.[6] The Ming fever arises to a large part from a widespread sense that there are two real and significant connections between the Ming and the present. First, people see parallels between the Ming and the People’s Republic. Second, people trace the origins of important current phenomena back to the Ming. The use of these connections, both for operating in the present and for debating and projecting particular images of the present and future, underlies the Ming fever.

Fig.7 Zhu Yuanzhang.

Fig.8 Mao Zedong.

The parallelism begins at a high level of generality, with the overall contours of the dynasty. According to the standard narrative taught today in Chinese schools, the rise of the Ming is the story of a strong, authoritarian founder, Zhu Yuanzhang, with an overarching social vision. After a period of terrible social turmoil and suffering, by sheer force of will the founding emperor expels foreign invaders, restores order, and sets about implementing that vision. But frustrated by his inability to realize his vision, to turn people and institutions to his will, he lashes out, causing the common people great suffering. In the end, much of his vision dies with him.

This narrative of the dynastic founder had already become ‘public property’ by the late Ming, as historian Sarah Schneewind points out in her introduction to a recent collection of essays on the political uses of Zhu Yuanzhang. Since then, his image has frequently been used to comment on, legitimize, or criticize other historical figures. One twentieth-century example is the biography of Zhu Yuanzhang written by the noted Ming historian Wu Han 吳晗 in the 1940s, which was widely interpreted as a veiled critique of Chiang Kai-shek.[7] Today, it is Mao Zedong to which people compare Zhu Yuanzhang. The parallels between the two are invoked often in my conversations. ‘Zhu Yuanzhang was very brutal. But he had to do what he did, or he could never have become emperor. He was just like Mao Zedong,’ one elderly villager told me in early 2009. (Here I should point out that there is a fundamental flaw in the ‘experimental design’ of this project. I am a historian of the Ming, and many of my interviews with rural people involve questions about the Ming. So of course people talk to me a lot about the Ming because that is what I ask them about.)

The possible parallels between Zhu Yuanzhang and Mao Zedong have long been obvious, and Mao even referred to them himself. Anita Andrew and John Rapp have written a book on this very subject.[8] But the parallelism that strikes readers of Those Happenings and viewers of The Great Ming Dynasty today goes beyond similarities between the two regime founders. Until the 1980s, the standard narrative of the Ming after Zhu Yuanzhang was that the dynasty grew backward, inward looking and corrupt. Today that view is changing. Readers of Ming history today learn that out of the early Ming era grew the prosperous, vibrant and mobile society of the sixteenth century, with its colorful urban life, diverse intellectual currents and relatively fluid gender relations. This picture of a society growing by dint of its people’s creativity, entrepreneurialism and diligence, ‘out of the plan’ established by the dynastic founder, resonates with the self-image of many people in China today. In other words, the standard narrative of the Ming, the version taught in schools today, follows an arc in which many people of the PRC today can trace their own story.

While the Ming fever is a popular phenomenon, an arcane debate in academic history in China laid the groundwork for the popular re-evaluation of Ming history. Reluctant to consign the Chinese to being passive subjects of their own history, Mao Zedong once proposed that China’s ‘feudal society’ had contained embryonic ‘sprouts of capitalism’ (zibenzhuyi mengya 資本主義萌芽) prior to the arrival of Western imperialism. In the Mao era some PRC historians sought to identify and analyze these sprouts and explain why they failed to develop into mature capitalism, in keeping with the Marxist expectations of universal patterns of progress. These efforts led to the discovery of the high level of commercial development in rural China and the extensive urbanization and rich urban culture of late Ming and Qing. Professional historians have been interested in these topics since the 1970s; through the media they now reach a mass audience of consumers of history.

Besides a general sense of the parallels between the arc of Ming history and recent developments in the PRC, there are also more specific and more explicitly normative parallels: ways in which people in the PRC today compare aspects of the contemporary situation with the Ming, in order to present a particular vision of the present. A recent example, though one clearly driven by state rather than purely popular concerns, came from the celebration of the sixtieth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), held in April 2009 in Qingdao. Xinhua News Agency reports compared the current situation with the Ming voyages. ‘During seven voyages by Zheng He’, one report declared, ‘China's own Christopher Columbus-like navigator, what was then the largest flotilla in the world imposed neither a colonial treaty nor claimed a piece of soil.’[9] Comparisons between the Ming voyages and China’s current naval build-up are obviously intended to convey a long history of peaceable intentions towards the outside world, in contrast to the baleful history of European and US imperialism.

Fig.9 Mao Zedong at the Ming tombs, 1952.

The new narratives of the Ming also challenge the stereotype of the Ming as a dynasty that turned inward, rejecting contact with the outside world. The emphasis on the voyages of Zheng He, comparisons with which the regime has also used in support of the ‘Going Out’ to the world (zou chuqu 走出去) policy proposed by Party General Secretary Jiang Zemin 江澤民 in the 1990s, is only part of the story. There has also been growing interest, again supported by less well-known academic history, to show that the end of the Zheng He voyages did not mean the closure of the country. On the contrary, private trade between southeast China and southeast Asia continued to flourish and helped to drive the newly discovered general prosperity of the mid Ming.

This in turn challenges old notions of the Ming as being fundamentally backward and stagnant. In the new narrative, the question becomes why the Ming did not go on to develop a full-blown overseas empire. Mao Peiqi’s answer is that ‘the real failure’ of the Ming was that the state never fully supported private commercial endeavours in the way that European countries would do in the coming centuries. His explanation for this failure is ‘uneven regional development’ and the fact that ‘political authority’ fell into the hands of people from these less economically developed regions, and later the Manchus.[10] It would be hard not to read this as argument as a commentary on contemporary China and a call for continued reform even at the cost of uneven economic development. In this sense the Ming fever serves as a way of talking about China’s relations with the larger world in the past, and therefore also in the present and future. Criticisms of insular and closed-minded groups who would turn back the clock on policies of engagement with the world for economic development and modernization have obvious resonance in today’s China.

These parallels rest on a sense that we can look to the past for instructive parallels to the present. There is a second rather different line of thinking that sees the Ming as important not as an analogy for modern China but as the source of modern China. In this approach, the Ming represents a critical historical convergence of the traditional Chinese order and the beginnings of modernity. As one avid historical blogger sums up the new story of the Ming,

In Ming China… thought was open-minded. In his attitudes and policies towards the outside world, not only was the emperor, the supreme political authority, not the representative of a conservative factions but he could be called the vanguard of opposition to conservatism. The economy and popular spirit attained a high level of development; philosophy and thought were extremely lively. Society was fundamentally different from what had come before. [Ming China] was the main beneficiary of economic globalization and it was the economic center of the world. It produced the world’s leading anti-authoritarian philosophers.[11]

There had been other times of openness to the outside world, most famously the Tang era. But many historians and non-historians in China now see the late Ming as fundamentally different from earlier periods, not only for its social and economic developments but also for the new trends of thought that arose alongside them. Seeing these intellectual movements as the birth of Chinese individualism, they find in the late Ming the origins of an indigenous Chinese modernity.[12] As one newspaper reporter commented in 2007, ‘the intellectual enlightenment in the scholarly world, of which Huang Zongxi 黄宗羲, Gu Yanwu 顧炎武 and Wang Fuzhi 王夫之 were representative figures, contained within it the origins of China’s modernization.’[13] In light of current efforts to revaluate traditional Chinese culture and construct a distinctively Chinese form of modernity, the Ming is widely seen as showing that Chinese culture contained the potential for modernity even without European imperialism and influence.

Prasenjit Duara has coined the term ‘hegemonic modernity’ to convey the idea that modernity is not a specific historical condition or phase but rather an ideology, one that has been constructed and institutionalized, and that has come to be dominant over other ideologies.[14] But the hegemony of modernity does not exclude the possibility that there can be multiple forms of modernity. The concept of an indigenous Chinese modernity with its roots in the Ming allows Chinese people today to challenge the hegemony of Western-style modernity without challenging the hegemony of modernity in general. This has important implications for thinking about China’s place in the world today. Perhaps China since the Ming has been following its own path to modernity. Perhaps it was diverted by the negative influence of Western imperialism but never completely lost the path, and today, by recognizing the value of its own traditions, it is returning to that path. If this is the case, then China’s current vision of modernity should be judged on its own terms, not held to falsely universalized standards of Western modernity.

Tensions and Contradictions

Searching the Ming for parallels with or origins of contemporary China can lead down some problematic paths. Efforts to make connections between past and present generate tensions or contradictions in how the past itself and its relations with the present are understood. By tensions I do not mean concerns about the validity of a given historical interpretation (though specific interpretations do generate endless debates on the Internet). Rather, my interest is in the logic by which a particular interpretation of an historical issue does the work it is desired to do in the present. Any specific use of history disrupts or undermines other uses. It may be that these tensions enhance the appeal of the Ming today. Perhaps the history of the Ming dynasty can serve as a venue for reflecting on contemporary issues precisely because one can use the Ming to make such a wide variety of arguments.

The ultimate contradiction in the use of the Ming as a celebratory or encouraging analogy with the present is that the Ming dynasty eventually fell. If people in the PRC today see themselves as following a narrative that follows a similar arc to the transition from early to mid Ming, the late Ming then becomes a harbinger of future dangers (though if it could survive the 276 years that the Ming lasted, the PRC would be doing rather well). The purpose of the analogy then becomes to break from the arc. This use of history as both model of the present and warning for the future is of course not new. The notion that one can learn from the past and thereby avoid repeating its mistakes runs through Chinese historiography. It is not even a new use of the Ming. In the 1930s, a previous outbreak of Ming fever tried to use historical analogy to rouse anti-Japanese resistance. That episode focused on the late Ming political failure to respond to Manchu threat on the borders, and celebrated those late-Ming heroes who sacrificed themselves in defense of the nation. Today there is no obvious immediate comparable threat on China’s borders. Nor is there much danger of palace eunuchs hijacking national politics, another factor to which late Ming weakness is typically ascribed. But some of the other causes of the Ming collapse: official corruption, elite disunity, public and private profligacy and a decline of public morals are very much concerns of the present day. Part of the appeal of the Ming today is surely that it provides a forum for comment on these problems of the present. Wu Guanzheng was of course thinking of the Ming in this way when he called on the apparat to promote Hai Rui.

Fig.10 Ming-era naval vessels.

A second tension in current accounts of the Ming relates to the dynasty that succeeded it, the Qing. Here the Ming fever intersects with two concurrent but distinct Qing fevers—a ‘high-Qing fever’ that celebrates the prosperity of the late-seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, comprising the reigns of emperors Kangxi 康熙, Yongzheng 雍正 and Qianlong 乾隆, and a ‘late-Qing fever’ that explores the dramatic changes of the nineteenth century and the efforts of statesmen and ordinary people to respond to the challenges of Western imperialism and internal crisis. Both of these fevers contain within them their own contradictions. These complicate efforts to find in them either the origins of modern China or parallels with China’s rise today. The logic of the high-Qing fever is troubled by the decline that followed so closely upon these reigns. If this was such a splendid age, what explains the disasters of the next century? As for the late-Qing fever, it is hard to make a case for a distinctive Chinese modernity with indigenous origins by looking at a period when Western imperialism seems to be the dominant historical force. If China’s finest statesmen could do nothing to stop foreign imperialism, what does this say about the potential for modernity inherent in Chinese culture?

But the two Qing fevers share a common element that may limit their effectiveness as historical analogy: the awkward fact of Manchu rule. When the history of the Ming was last deployed in the 1930s to rouse patriotic sentiments against the Japanese threat, the foreign origin of the Manchus was central to the effectiveness of the parallel. The Han Chinese Ming was to the Manchu invaders as the Republic of China was to the Japanese. But in PRC official perspective today, the Qing is celebrated as the multi-ethnic imperial predecessor of today’s multi-ethnic harmonious society. So at least within officially sanctioned versions of history, the analogy of anti-Manchu resistance can no longer play a mobilizing role. On the other hand, the rising influence of nationalism in contemporary China, both nationalism contrived and manipulated by the state and also nationalism bubbling up from below, means a growing contradiction between two views of the Qing, as a great Chinese empire and as a foreign empire ruled by foreign invaders. This contradiction came to a head in late 2008, when the Qing scholar Yan Chongnian 閻崇年 was assaulted at a Shanghai book-signing (see Danwei for more details of this case.). Yan writes of the Qing as a time of merging and exchange between the different ethnicities that make up the Chinese people. His assailant was offended by this effort to whitewash what he saw as the reality of the Qing entry into China—foreign invasion. On the Internet Yan was ‘outed’ as an ethnic Manchu. One can read this event as expressing a tension between authoritative narratives of the Qing—authoritative in the sense of being linked to political authority—and popular nationalist understandings.

Fig.11 A Zheng He-era ship.

Many popular nationalist interpreters of history favor the Ming, the last imperial dynasty whose ruling house was ‘Han Chinese’, over the Manchu Qing. As one scholar put it, ‘The Qing has the additional element of ethnicity, of a foreign ethnic group as rulers. If you want to use the past to look at the present, today there is no such factor.... If we get rid of this factor, what we’re left with is the Ming.’ Or in the words of an anonymous commentator on an article about the Ming fever, ‘Only with the revival of true Han culture can there be a revival of China.’[15] (The fact that the expansion of the empire to roughly the boundaries of China today happened in the Qing tends to be forgotten by Han nationalist critics as does the slipperiness of the very concept of Han Chinese.) In today’s China, the politics of historical representation embodies a tension between a larger but multi-ethnic Qing empire and a smaller but Han-ruled Ming empire. Both as a mirror and as a source of modern China, the Ming lies in uneasy tension with the Qing. The uneasiness reflects contesting visions of the Chinese nation past, present, and future. Whether individuals are more interested in the Ming or the Qing as the source for their historical analogies reflects their different positions on the question of what is China’s most important inheritance from the past, and therefore on the character of China today.

Conclusions

Paul Cohen has written that to live on as myth, an event or a person must embody themes or characteristics that are pertinent to later times.[16] To put this another way, certain eras or issues are more likely to generate fevers, to become ‘feverish’, precisely because of their perceived relevance to the present. The current Ming fever, I have suggested, has arisen at least in part because many people perceive the Ming as relevant or useful as a set of analogies to the present, as a source for important dimensions of the present, and therefore as a resource for reflecting on the present. Many of those involved in the Ming fever agree. As the blogger Dangnian puts it, ‘People who read (kan 看) history do so in order to look at (kan 看) themselves. Historical fevers are a refraction of the confusion and puzzlement of people who live in a time of transition.’[17] Another popular blogger compares the Ming fever to the passion for local history in Taiwan a few decades ago. ‘Perhaps such historical fevers [are a response to] a general anxiety in times of transformation.’[18]

Fig.12 A poster for Dangnian Mingyue’s play Ming

Like so many other areas of life in the PRC today, popular interest in history is shaped by—but not fully determined by—the two great forces of state and market. Despite the power of the state to impose an authoritative vision and of the market to offer a commodified one, many of the most interesting aspects of popular history lie in the interstices of the two. History retains a striking capacity to serve as a venue for commenting on the present and future, and therefore as a site of competition for the right to speak. In other words, my argument here is that we should pay attention to the presentation of history in China today because history is to some degree a venue for politics in the broadest sense. The history of the Ming is interesting to people in China today not only because it is entertaining, but because the writing of this history shapes collective self-understanding, simultaneously legitimizing some aspects of the current order while critiquing others. Perhaps the Ming is feverish—it generates heated passions—precisely because of the limits on serious open discussion of political and social issues in China today. We might even see historical fevers in China today as another manifestation of the very forces that in other contexts lead to overt dissent and protest.

Much of the attention to the recent sixtieth anniversary of the People’s Republic looked to the future. But many Chinese people are also thinking about the past. The past remains both a mirror for reflecting on the present and a resource for constructing the future. This was more true than ever in a year of historical anniversaries like the one just past, some of which were officially commemorated, others suppressed, all of them contested. Historical fevers inhabit an ambiguous space between a China of recurring patterns and a China moving forward into its own distinctive modernity. Popular narratives about the past embody ambiguities and unresolved tension. This is not just because of the inadequacies of the historical evidence or the challenges of representation, but because of the ambiguities and tensions that surround China’s current situation and future course.

Notes:

* This article is based on a paper presented at a conference on ‘The People’s Republic of China at 60’ at the Fairbank Center, Harvard University, 1-3 May 2009. I would like to thank Bill Kirby, the organizer of the conference, for permission to publish this article in advance of the conference volume. For comments and suggestions, I am grateful to Macabe Keliher, Sarah Schneewind, Wei Yang, Ray Lum, Wang Xiaoxuan and the editor of the present journal.

[1] Guo Li and Li Pei, ‘Looking for the True Character of the Last Han dynasty’ (Tanxun zuihou yige Han wangchaode benlai mianmu), Southern Daily (Nanfang ribao), 4 March 2007.

[2] The controversy is described in ‘On the Those Happenings of the Ming Dynasty affair on Tianya’ (Ji Mingchao naxie shi’er Tianya shijian), at: http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_4991e77f0100052e.html.

[3] Liu Qiang, ‘On Those Happenings of the Ming Dynasty’ (Shuoshuo Mingchao naxie shi’er), Study Theory (Xue lilun), 2008, no.5.

[4] Matthias Niedenführ, ‘Historical Revisions and Reconstructions in History Soaps in China and Japan’, in Steffi Richter, ed., Contested Views of a Common Past: Revisions of History in Contemporary East Asia, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

[5] ‘The Central Discipline and Inspection Committee Participates in the Making of ‘The Great Ming Dynasty’, promotes Hai Rui’s anti-corruption spirit’ (Zhongjiwei canbo Da Ming wangchao xuanchuan Hai Rui fanfu jingshen), 3 March 2007, at: http://www.hq.xinhuanet.com/news/2007-03/04/content_9416253.htm.

[6] Mao Peiqi argues that market forces of supply and demand are behind the current Ming fever. A high-Qing fever had begun in about 1996, and after a decade, he writes, ‘aesthetic exhaustion’ had set in: people were hungry for something fresh. Surrounded by obvious signs of Ming greatness in the form of relics like the Forbidden City and the Great Wall, Mao continues, the general public, the consumers of history, turned their interest to the dynasty that produced such monuments.

[7] Q. Edward Wang, ‘Victor or Villain? The Varying Images of Zhu Yuanzhang in 20th Century Chinese Historiography’, in Sarah Schneewind, Long Live the Emperor: Uses of the Ming Founder across six centuries of East Asian History, Minneapolis: Society for Ming Studies, 2008; and, Mary Mazur, Wu Han, historian: son of China’s times, Lanham MD: Lexington Books, 2009.

[8] Autocracy and China’s rebel founding emperors: comparing Chairman Mao and Ming Taizu, Lanham MD: Rowan and Littlefield, 2000. For a more recent discussion, see Geremie R. Barmé, ‘For Truly Great Men, Look to This Age Alone—was Mao Zedong a New Emperor?’, in Timothy Cheek, ed., A Cambridge Critical Introduction to Mao Zedong, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming 2010.

[9] Yan Hao, ‘Commentary: Chinese ocean presence a must for peaceful development’, at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2009-04/23/content_11246107.htm.

[10] Chen Xiang, ‘Why is Ming History so Hot?’ (Mingshi weishenme zhenme re?), Chinese Reader (Zhonghua dushu bao), 24 January 2007.

[11] Chen Hao, ‘Alas, Our China is Already a Thing of the Past—the Ming dynasty’ (Naihe Jiangshan yicheng wangshi—Mingchao), 1 February 2007, at: http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_4b4e45fb010006rx.html.

[12] Compare Theodore de Bary, ‘Individualism and Humanism in Late Ming Thought’, in Self and Society in Late Ming Thought, New York: Columbia University Press, 1970.

[13] ‘Speaking clearly about the Ming dynasty’ (Mingming baibai shuo Mingchao), Jilin Daily (Jilin ribao), 15 March 2007.

[14] Prasenjit Duara, The global and regional in China’s nation-formation, New York: Routledge, 2009, pp.8-9.

[15] ‘This is the Year of the Ming’ (Jinnian shi Mingnian), News Magazine (Xin shiji zhoukan), March 2007, at: http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_4bf9fb3e010007uq.html.

[16] Paul Cohen, Speaking to History: the story of King Goujian in twentieth-century China, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

[17] ‘How did the Ming dynasty become a tasty snack?’ (Mingchao za chengle xiang bobo?), Cross-strait Consumers Journal (Haixia xiaofei bao), 1 March 2007, at: http://www.66163.com/Fujian_w/news/fjgsb/319/14.pdf.

[18] Guo Li and Li Pei, ‘Looking for the True Character of the Last Han dynasty’, op. cit.

|