|

EDITORIAL

No. 7, September 2006

CHINA'S INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE

In 2006, China embraced the notion of 'intangible cultural heritage' with all the enthusiasm and publicity once only reserved for a new economic reform measure. In this issue we return to the topic of Intangible Cultural Heritage, previously the focus of our Second Issue (June 2005). In the first half of 2006, the State Administration of Cultural Heritage (SACH), the massive bureaucracy under the Ministry of Culture once known as the State Cultural Relics Bureau, issued two lists of more than 500 cultural heritage items, embracing folk tales, ethnic festivals, regional musical, dramatic and storytelling art forms, handicrafts and even sacrificial cults. Governmental and cultural organisations across China have also held numerous meetings, staged conferences and exhibitions, and received further nominations of 'intangible cultural heritage' items. For the central government, the UNESCO-sponsored concept of 'intangible cultural heritage' has enabled cultural bureaucrats to sidestep uncomfortable talk of history and tradition, and it has provided conservationists with new notions for discussing and extending heritage protection.

In our Editorial we look at the new approach to the past that these listings make possible, and in our Features section also examine SACH's preliminary listings in detail ('A Tale of Two Lists'). For reference purposes, we append and translate the two lists issued by SACH in PDF format.

National, local and even international political interests often find themselves in conflict regarding the provenance and ownership of cultural items. In Articles, we examine 'The Rehabilitation and Appropriation of Great Wall Mythology', focusing in particular on the listing of the legend of Meng Jiangnü and Chinese ancient 'soccer' as intangible cultural heritage items. We also include a recent oral history interview by the writer Sang Ye under the title 'Living with the Past', in which he talks with a retired caretaker at Jade Gate Pass at the westernmost point of China's Great Walls.

The need to document and define items of cultural heritage nominated by SACH, as well as by the other ministries and cultural authorities of central, provincial and local governments, represents a massive intellectual undertaking. Little solid new scholarship on intangible cultural heritage items actually exists. In Intellectual News, we review one of the few contributions to this new field of studies of intangible cultural heritage that has recently appeared, Li Yun and Zhou Quangen's study of Tibetan opera.

In this issue, we also continue to provide an overview of other heritage issues through our regular digest of archaeological and heritage news briefs, and Jeremy Clarke SJ reviews the recent exhibition of Qing imperial treasures in the Musée Guimet in Paris.

Approaching the Past:

Preparing an Inventory of Intangible Cultural Properties

Fig. 1 Cover of Issue 1 of the newly published journal China Intangible Cultural Heritage (Zhongguo feiwuzhi wenhua yichan), published in May 2006 by the Zhongguo Yishu Yanjiuyuan (China Arts Academy).

China has within its borders one of the largest, if not the largest, number of oral and musical literature traditions of any country in the world. This is not only because China is home to more than fifty disparate ethnicities, but also because the majority ethnic Han culture is fragmented into so many regional dialect groups. Even today, it is estimated that roughly 40% of the Chinese population does not speak standard Chinese or putonghua.

The concept of 'intangible cultural heritage', first coined by conservationists in the 1980s and subsequently 'codified', or at least 'sketched out', under the auspices of UNESCO, has found a welcoming home in China. Although sixty states have ratified UNESCO's Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage which came into force on 20 April 2006, none has more wholeheartedly embraced the concept than China. News items on the topic appear in the press on a daily basis, and specialist magazines on this aspect of heritage preservation are now being published. (Fig. 1) Although China's enthusiasm may have initially been premised on the possibility of having many cultural properties acknowledged internationally as World Masterpieces of Oral and Intangible Heritage, UNESCO has now discontinued such listings. Yet media attention to 'intangible cultural heritage' issues in that country dramatically increased in 2006. In China, the edifice of intangible cultural heritage now occupies centre stage as the concept that will enable the preservation of aspects of traditional culture in danger of being lost forever. It is invoked in major cultural policy statements and the ever-increasing use of the term shows that in China 'intangible fever' might provide the impetus and framework for what may well be radical new approach to culture and tradition.

'Intangibility' and 'Spirituality'

Zhou Heping, Vice-Minister of Culture, has made it clear that 'intangible cultural heritage', like Deng Xiaoping's socialism, must have unique Chinese characteristics. The Chinese construct of 'intangible cultural heritage' (feiwuzhi wenhua yichan) is grounded in an artificial distinction between the material (materialism) and the spiritual (idealism), a bifurcation that is epistemologically and ontologically less readily acceptable by Western conservationists and heritage theorists than by Chinese cultural officials and ideologues who have long been familiar with a clear-cut rhetorical and ideological dichotomy between materialism and idealism. In the post-Mao era, the Chinese Communist Party sought to salvage 'spiritual' values and 'spiritual' civilisation from the wreckage of 'dialectical materialism' and 'historical materialism', two philosophies or rather ideologies that guided and sustained PRC intellectual life for nearly four decades. However, these efforts went far beyond the perceived need to create socialist ethics and a sense of public order. In the hands of ideologues, the concept of a spiritual or intangible realm that encapsulated the belief systems and thinking of society was distorted by efforts to enforce conformity. Such efforts, as epitomised by the repressive 1983-84 campaign against 'spiritual pollution', were heavy-handed and echoed the political purges and campaigns of the Maoist era. The new Chinese coinage of 'intangible cultural heritage' has enabled the party's ideological watchdogs to move away from the unappealing and discredited 'spiritual' formulae, even though 'spiritual civilisation' (jingshen wenming) and 'intangible cultural heritage' are both given space in the 'State Outline Program of Cultural Development in the 11th Five-Year Plan Period', issued by the Office of the Central Committee of the CPC and the Office of the State Council on 13 September 2006.

Ironically, the concept of feiwuzhi (used for 'intangible'), which in English literally translates as 'non-material', is premised on the existence of a 'material' (wuzhi) category, a dialectical notion which Marxism-Leninism can readily accommodate. For Chinese conservationists, however, what we might term 'material heritage' is conventionally translated as 'wenwu', mawkishly translated into English and endorsed by long-term usage as 'cultural relics'. (China's State Cultural Relics Bureau has attempted to divest itself of the antiquarian implications of 'relictology' and restyled itself in 1988 the State Administration of Cultural Heritage, or SACH, even though no attempt has been made to date to change its Chinese title, Guojia Wenwuju.) The neatness of the formulation 'intangible cultural heritage' is of course mere sophistry, but Chinese Marxist dialectical materialism always rested on a linguistic substratum of what historians of Chinese philosophy called 'primitive', 'primordial' or 'naïve dialectics'.

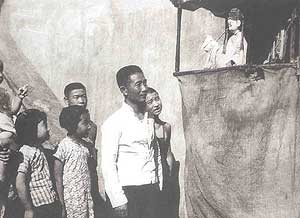

Fig. 2 Vintage photograph of a street puppet show ( mu'ouxi) in the Tianqiao district of Beijing. These performances were swept from the streets in the late 1960s because they were deemed to be feudal, superstitious and pornographic, and have only been revived in 'theme park' settings in recent years. Although 'puppet shows' are listed as intangible cultural heritage property no. 236 (IV-92), Beijing municipality is not one of the twelve nominating administrative bodies. Photo source: Zhongguo feiwuzhi wenhua yichan, 2006:1, p.46.

The notion of 'intangible cultural heritage' has also enabled cultural policy makers to sidestep the moralising and judgmental categories of 'quintessence' (jinghua) and 'dross' (zaobo) that informed PRC historiographic morality and attitudes to tradition and specific aspects of the Chinese past, and provided liberation from the pejorative notions of 'superstition' and 'feudalism', rubrics once used to damn much of China's pre-1949 tradition. Nevertheless, 'intangible cultural heritage' is intended implicitly to preserve the 'best' of traditional culture. For the moment no one is suggesting that opium smoking, foot-binding or local practices of witchcraft, for example, be listed as aspects of China's 'intangible cultural heritage', but impediments to conservation efforts are still thrown up by the moralistic freeze-frame of the High-Maoist period as evidenced by the vociferous opposition of members of the general public to recent conservationists' efforts to preserve an ancient bordello in Changsha which is a rare example of Ming dynasty architecture.

China's cultural policy makers have thus been able to use 'intangible cultural heritage' to acknowledge, accept, document, resuscitate and preserve aspects of China's tradition that were once threatened or slated for condemnation, destruction, suppression and elimination. (Fig. 2) At the same time, the notion of 'intangible cultural heritage' has recast many historical practices and traditions as museum exhibits or decorative items that can no longer make an ideological impact on current beliefs, customs and lifestyles.

Publicising Intangible Cultural Heritage

China's traditional cultures, although no sense of the plural, plurality or multicultural nature of the latter noun is evident in either the Chinese term Zhongguo wenhua or for that matter Zhonghua minzu (correctly translated 'Chinese nationalities' or 'peoples' if China is held to be a 'multi-ethnic' nation), are now reconstituted as a neutral smorgasbord for a new generation of diners. The necessary first step in all of this has been selecting the dishes for the banquet. UNESCO's guidelines on what constitutes 'intangible cultural heritage' are suitably vague: language, performing arts, social practices, rituals and festive events, culinary traditions, knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe, as well as know-how linked to traditional arts. While sacred sites, cultural landscapes, and cultural spaces are also aspects of UNESCO's criteria, Chinese conservationists have felt less comfortable with these categories and so have dropped them from their own selection criteria.

Fig. 3 View of the foyer of the exhibition 'Successes in Conserving China's Intangible Cultural Heritage' in the National Museum of China, staged by the Ministry of Culture, Zhongguo Yishu Yanjiuyuan (China Arts Academy) and a number of other central government ministries, 12 February-16 March 2006.

On 31 December 2005, the State Administration of Cultural Heritage (SACH), under the auspices of the Chinese Ministry of Culture, released to the general public its first list of intangible cultural heritage items. This preliminary list was an inventory of 501 items, said to have been selected from 1,315 nominations. An exhibition titled 'Successes in Conserving China's Intangible Cultural Heritage' in the National Museum of China (NMC) was staged by the Ministry of Culture and a number of other central government ministries to publicise the list. Curated by SACH and by Zhongguo Yishu Yanjiuyuan (variously translated in the Chinese media as either the China Arts Academy or China Art Institute), the exhibition ran from 12 February to 16 March 2006. (Fig. 3) The exhibition was prepared in a rush; labelling was slapdash, no catalogue was prepared and most displays comprised only notice-boards, photographs and monumental compendia of Chinese medical and dramatic anthologies published in the 1980s and 1990s. One prestigious multi-volume encyclopaedia was arranged as a pyramid occupying valuable gallery floor-space.

Pride of place was given to photographs documenting public appearances by China's top leaders at heritage-related events. Like a big-character poster display from earlier times, the Preliminary List itself was a central feature of the exhibition. The Communist Party's commitment to prioritising cultural heritage awareness in the cause of Chinese national unity was highlighted by the well publicised visit on 13 February to the exhibition by Politburo member Li Changchun, effectively China's propaganda chief. He was quoted by Xinhua News Agency as stating during his visit that, 'The protection of intangible cultural heritage and maintaining continuity of the national culture constitute an essential cultural base for enhancing cohesion of the nation, boosting national unity, invigorating the national spirit and safeguarding national unification'. His statement is the latest twist to the CPC's long-standing policy of 'using the past to serve the present', even though it represents a 180 degree turnabout from the Maoist commitment to the elimination of remnants of China's feudal culture. The rush to put together the exhibition was dictated by the need to attract the attention of China's CPC and non-Party leaders attending the annual political meetings in the Great Hall of the People across Tiananmen Square from the NMC. Perhaps this could be described as the first hijacking of the NPC and CPPCC meetings by conservationists!

Fig. 4 Tibetan thangka in the Repkong style depicting White Tara. Repkong, known in Chinese as Huangnan, is a major centre of thangka painting in Qinghai and local monks receive commissions to create paintings from as far afield as Lhasa and even the USA. Although Tibetan thangkas are inscribed as intangible cultural heritage property no. 313 (VII-14), only styles from Tibet and Sichuan are nominated. Photo source: Zhongguo feiwuzhi wenhua yichan, 2006:1, p.108.

Despite the profusion of signage in the exhibition, there were modest but impressive displays of ancient or ethnic musical instruments, items of ethnic dress, a large ancient loom from Nanjing once used to produce elaborate silk brocade, and vivid Yangliuqing New Year prints from Tianjin, to single out only the more eye-catching pieces. The exhibition was also enlivened by live performances: Shaolin Temple kungfu martial arts displays, demonstrations of weaving, performances on the guqin (sometimes, but erroneously, called the Chinese lute) by Professor Li Xiangting of the Central Conservatory of Music, Hokkien puppet shows and demonstrations of Tibetan thangka painting from Repkong (Huangnan) in Qinghai province. (Fig. 4) The exhibition is said to have been visited by 350,000 people. Of course, many visitors were 'press-ganged' into attending by their schools and work units. Nevertheless, the attendance figures are impressive.

In June 2006, SACH issued a second list of intangible cultural heritage items, totalling 518 items. Following the release of the second list, a travelling exhibition was organised to publicise it. On 1 September, the exhibition opened at the reconstructed Yongdingmen Gate in Beijing, and from the capital the exhibition will travel to Shanghai, Kunming, Chengdu, Chongqing, Jinan and Xi'an.

Like the first list, the second was divided into ten major categories: folk literature; folk music; folk dance; traditional drama; quyi; acrobatics and contests of skill; folk arts; handicraft skills; traditional medicine; and, folk customs. At first glance, the two lists seem largely identical, with only a discrepancy of 17 items separating the two. According to representatives of the State Intangible Cultural Heritage Protection Research Centre, the second list, totalling 518 items, is a little broader in scope and more finely calibrated than the preliminary list of 501 items.

Conclusion

However, a closer comparison of the two lists and a careful examination of the second list, which we undertake in our Features section (see: 'A Tale of Two Lists' and 'Heritage and Commercialisation'), reveals that the new enthusiasm for nominating and listing items of intangible cultural heritage might not necessarily always serve the cause of preservation. By neutralising the power and force of tradition, items of 'intangible heritage' can be the more easily commodified, exploited and commercialised. [BGD]

|