|

|||||||||

|

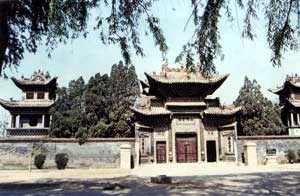

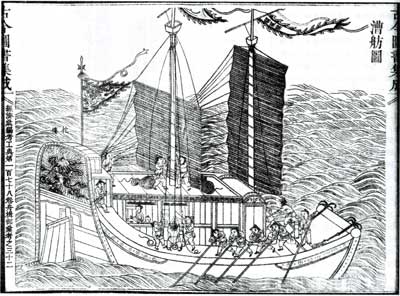

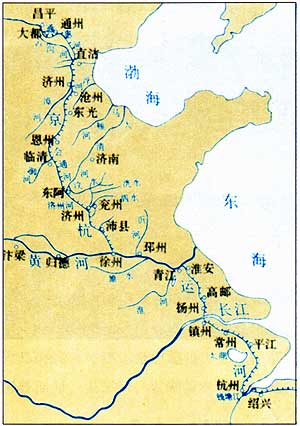

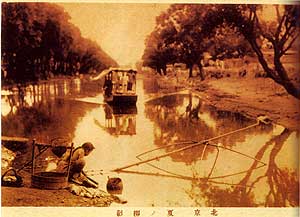

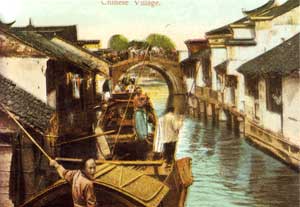

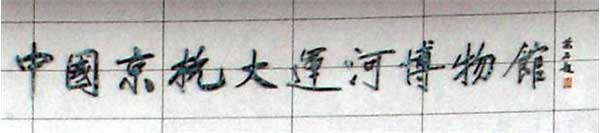

EDITORIALNo. 9, March 2007HERITAGE OF THE GRAND CANALIn March 2007, the Grand Canal became a focus of media attention in China as government advisors and legislators discussed whether it should be listed for world cultural heritage status. In this issue we focus on topics related to the history, heritage and conservation of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal (Jing-Hang yunhe). Today, long stretches of the 1,800 kilometre-long waterway are polluted or impassable, but many other parts of the canal are working waterways which annually shift three times more cargo than is moved by rail between Beijing and the Lower Yangtze region. The massive canal system was constructed to address the needs of administration, human transport, grain movement and flood control, yet it also altered the cultures of the areas it connected. Thus, like the Great Wall, the Grand Canal is a feat of ancient engineering that defines a vast and distinctive cultural landscape. Completed in the Sui dynasty (581-618), the Grand Canal laid the formation for the prosperity of the Tang and subsequent dynasties. In this issue, two feature articles, 'The Southern Expeditions of Emperors Kangxi and Qianlong' and 'Acquiring Gardens', address aspects of the political role and cultural significance of the Grand Canal during China's period of greatest prosperity, the 17th and 18th centuries. The latter article adding to our reflections on Yuanming Yuan (the Garden of Perfect Brightness), the focus of our December 2006 issue. We also review China: The Three Emperors, 1662-1795, which documents those two centuries in terms of their artistic achievements. Also presented in this issue is 'Chinese Myths of the Deluge,' an article discussing the revival of the cult of Da Yu, 'Great Yu', one of the earliest names in the history and mythology surrounding Chinese hydrology. The Challenge of Grand Canal Heritage Fig. 1 Plaque commemorating the initiation of the project to have the Grand Canal listed as a World Heritage site. Courtesy of the website: culture.people.com.cn. The conservation of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal was on the agenda of the most recent sessions (3-15 March 2007) in Beijing of China's top political advisory body, the CPPCC (Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference). For the second year running, a number of delegates lobbied to have the Grand Canal listed within five years as a World Heritage site (Fig.1), but conservation of the world's longest man-made waterway, stretching nearly 1,800 kilometres from China's north to south, poses a monumental challenge. One thousand km of the original Grand Canal remain fully operational as a transport route. Three times the amount of freight is moved along the Grand Canal annually than is transported by rail between Beijing and Shanghai, and the industrial output of the 18 major cities along the canal represents one fifth of China's industrial output. However, stretches of the canal, mostly in the north, have dried up, become impassable or been reduced to industrial cesspools. Yet the canal flows through some of China's most significant historical cities, and cultural monuments line its banks in many places. (Figs.2, 3&4)  Fig. 2 View of the Grand Canal on the outskirts of Changzhou Source: Fu Chonglan, Zhongguo yunhe zhuan (Story of the Grand Canal of China), Taiyuan: Shanxi, 2005. Persistent public calls for the conservation and protection of the Grand Canal were first heard in 2005, and a drive by CPPCC delegates to champion the cause began in earnest in 2006. However, the conservation limelight in 2006 was stolen by the government's announcement of China's first list of intangible cultural heritage properties and the accompanying performances and exhibitions, as well as by the proclamation of the second Saturday in June as Cultural Heritage Day, acts initiated by the State Administration of Cultural Heritage. However, in March 2006, a 40-member panel of political advisors and experts was formed to address the issue of Grand Canal conservation, after 58 CPPCC members had jointly proposed measures to immediately initiate protection work on the canal. In May 2006, the panel conducted an inspection tour of the entire canal, and their findings have both appeared in the press and been presented formally at this year's CPPCC session.  Fig. 3 Photograph of Precious Girdle Bridge straddling the Grand Canal in Suzhou. Source: Photograph among frontispiece illustrations in An Zuozhang, Zhongguo yunhe wenhua shi (History of the culture of the Grand Canal), Jinan: Shandong Jiaoyu Chubanshe, 2001, vol.1, n.p.  Fig. 4 Photograph of the Shaanxi Merchants Guild in Liaocheng (photograph in the collection of Liaocheng Municipal Museum). Source: An Zuozhang, n.p. Introduction to the Grand Canal Fig. 5 Photograph of the Grand Canal in Wuxi in 1995. Source: An Zuozhang, n.p. The Grand Canal was the major cultural and economic arterial system linking north and south China for nearly one and a half millennia. Like the Great Wall, it defines a major cultural landscape in which it is the central engineering monument. Unlike the Great Wall, it was designed to serve as a transport route that provided an economic and cultural conduit through the heartland of the nation. (Fig.5) China's civilisation was defined and sustained by its large-scale hydraulic enterprises, according to some scholars. Karl Wittfogel drew on Marx, Engels, and Weber to argue that the control of the water supply for irrigation was the basis of what he termed an 'Asiatic mode of production' and of a powerful and exploitative bureaucracy spawned by water control.[1] Wittfogel's notion of 'oriental despotism' has fallen by the wayside, but the reworking of his concepts of a 'hydraulic monopoly' and a 'hydraulic bureaucracy' continue to have application to Chinese history, even though historians today acknowledge the existence of much more flexible and subtle relationships between emperors, bureaucrats, merchants and the vast majority of the population. Any introduction to the geography of the Grand Canal is necessarily complex, because its construction, like that of the Great Wall, was carried out intermittently and over a long period of time. Today it represents an accretion of different canal systems which, for the sake of clarity, can be reduced to six major units extending from Beijing in the north to Hangzhou in the south. The Grand Canal, the precise length of which is generally accepted to be 1,794 km, comprises the following sections: (1) North Canal (Bei Yunhe) and Tonghui River (Tonghui He), running from Beijing to Tianjin; (2) The South Canal (Nan Yunhe), Tianjin to Linqing; (3) Shandong Canal (Lu Yunhe), Linqing to Weishan lake; (4) Central Canal (Zhong Yunhe), Weishan lake to Huai'an; (5) Inner Canal (Li Yunhe), Huai'an to Zhenjiang; and (6) The Canal South of the Yangtze (Jiangnan Yunhe), Zhenjiang to Hangzhou. The most accessible description of the major features of each of these sections is available on-line in Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Canal_of_China, while an excellent map of the entire canal is also available online by clicking on the link to the map on Encarta http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761572005/Grand_Canal_(China).html. Brief History of the Grand CanalThe history of the Grand Canal has served as a thermometer of the health of the dynasties that participated in its construction, unlike the Great Wall which was a better gauge of the pathology of its builders. Although Chinese mythology or proto-history casts Yu as the first man to have constructed channels to drain water-logged tracts of land (see 'Chinese Myths of the Deluge', in this issue of China Heritage Quarterly), historical records award the more specific distinction of initiating canal construction in China to Sun Shu'ao, prime minister of the state of Chu in the Spring and Autumn period. 1. Pre-Qin Period Fig. 6 Photograph of an ancient town on the Yellow River below Huai'an. This town is located at the point where the Hangou canal entered the Huai River, and once formed part of Beichen township (zhen). In 1415, the water from Guanjia Lake west of Huai'an was channelled into the Huai River through Yachenkou, and so the canal route was altered to run to the west of Huai'an. Hexia at the mouth of Guanjia Lake was located between the Grand Canal and the Yellow River and so it became a strategic point in the grain transport system. Because the aptly named town of Hexia (lit., 'under the river') was located below the level of the Yellow River, it became famous. At the beginning of the Ming dynasty, the Huaibei yanyun fensi shu (Branch Offices of the Northern Huai Salt Transportation Bureau) were moved from Lianshui to Hexia, and because Northern Huai salt was produced in Haizhou and the treatment plant was in Shanyang, Hexia became a place through which the Huaibei salt merchants had to pass, and so many constructed mansions, gardens and guild houses there. Source: Photograph by Li Dihua, published in Zhongguo wenhua yichan, 2006:1, p.40. Once irrigation was mastered, early canals were also built for the transport of troops and grain. In 613 BCE, Sun Shu'ao oversaw the excavation of a canal connecting the Jingjiang and Hanshui rivers, as well as another connecting Chaohu lake and the Feishui river. These were China's earliest canals, but it was Fuchai, King of Wu, who in 486 BCE supervised the excavation of Han Gou (Han Canal) (Fig.6), a protean part of the Grand Canal network. Han Canal was an extension of the moat constructed by King Fuchai around a walled city in what is now the north-western part of present-day Yangzhou (Fig.7), and it led in a north-westerly direction to Mokou at Huai'an where it opened into the Huai river. (Fig.8) This waterway, 185 km in length, was intended for transporting troops.  Fig. 7 Photograph of Wenfeng Pagoda on the banks of the Grand Canal in Yangzhou. Source: Photograph among frontispiece illustrations in An Zuozhang, n.p.  Fig. 8 View of the Grand Canal outside Huai'an city Source: Fu Chonglan, Zhongguo yunhe zhuan, n.p. 2. The Qin-Han EmpireDuring the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE), the remarkable Lingqu canal was constructed. This connected the Xiangjiang and Lijiang rivers, thereby joining the even larger Yangtze and Pearl River systems, aiding Emperor Qin Shihuang in his conquest of the Lingnan region, roughly equivalent to present day Guangdong province, and promoting cultural and ethnic interaction between north and south. The project is generally deemed to be a miracle of ancient engineering. In the Western Han dynasty (206 BCE–CE 23), a network of canals was also constructed in the vicinity of the capital, Chang'an; these led north and south of the Yellow River, guaranteeing the supply of grain and other necessities to the capital and developing relations between the Guanzhong plain and eastern China. These projects demonstrated the geopolitical role canals played in nation building, and inspired the later Sui dynasty emperors and their engineers. 3. Sui Dynasty Fig. 9 Song dynasty Grand Canal grain boat (caofang). Source: Gujin tushu jicheng, reproduced in Wang Guanzhuo ed., Zhongguo guchuan tupu (Illustrated ancient Chinese boats), Beijing: Sanlian Shudian, 2000, p.192. Following the long period of political disarray after the demise of the Han dynasty, the Sui dynasty (581-618) reunified China, ushering in a period of economic prosperity. Canal construction began under Emperor Wen (Yang Jian, r.518-604) who, in 584, commanded Yuwen Kai to construct a canal running from his newly constructed capital of Luoyang (Dongdu, Eastern Capital) eastwards to the confluence of the Wei and Yellow rivers. The canal, called Guangtong Qu, was designed to transport grain to the food-deficient areas around Luoyang and to overcome the silting that plagued the Wei and Yellow rivers. The new canal, just under 200 km in length, was completed in 589. The work proceeded quickly, as it followed the route of a canal built seven centuries earlier. Grain could now also be brought to the capital from Shanxi down the Fen and Yellow Rivers, and then along canals. (Fig.9)  Fig.10 Photograph published in 1987 of the Gongchen Bridge at the southern end of the Grand Canal in Hangzhou. Source: Photograph among frontispiece illustrations in An Zuozhang, Zhongguo yunhe wenhua shi (History of the culture of the Grand Canal), Jinan: Shandong Jiaoyu Chubanshe, 2001, vol.1, no page numbers. Emperor Wen's successor, Emperor Yang (Yang Guang, r.605-618), ordered further extensions of the canal system, on assuming the throne in 605. Work began on the Tongji Qu which linked Luoyang with Sizhou on the Huai river and connected with a very old canal running southwards from Huaiyin to the Yangtze river at Jiangdu. More than a million labourers were recruited to dredge the new canal and to lay royal roads and plant trees along its banks. In 608, work began on the Yongji Qu that ran to Zhuojun (today's Zhuozhou) in the vicinity of Beijing. In the year 610, Emperor Yangdi ordered the construction of another canal from the Yangtze River opposite Yangzhou to run southwards to Hangzhou (Fig.10), a distance of approximately 400 km. The canal network brought grain and taxes to the capital, but the project also had political and military objectives enabling troops to be fed and deployed over a wide area. The canal also played a role in Emperor Yangdi's unsuccessful attempt to conquer the Koguryo kingdom. The massive expenditure of labour on this gargantuan project weakened the dynasty, yet the canal system, which then totalled roughly 2,500 km in length, became one of the major underpinnings of the prosperity of the subsequent Tang dynasty (618-907). Although the Tang and the Song (960-1279) maintained the canal and engaged in limited further construction, the basis of the economic prosperity of these two dynasties had been laid in the Sui dynasty. 4. Yuan, Ming and Qing Dynasties Fig.11 Map showing the route of the Grand Canal during the Yuan dynasty. Source: Originally in Chinese Atlas of Natural Geography (2nd edition) published by Zhongguo Ditu Chubanshe as reproduced in Zhongguo wenhua yichan, 2006:1, p.20.  Fig.12 Diorama depicting the Jishuitan grain wharves in Yuan dynasty Dadu (Beijing), Capital Museum, Beijing. The Yuan dynasty (1271-1368) was another period of major canal construction. (Fig.11) Engineers streamlined stretches of the canal by eliminating many of the bends, and consolidated the Jizhou and Huitong river systems. They effectively reduced the distance to be traversed from the southern end of the canal to the capital Beijing by almost 700 km. The Yuan engineers also opened a canal leading from Tongzhou in south-eastern Beijing to Jishuitan (Fig.12) on Houhai, the 'Rear Lake' adjacent to Desheng Men gate in today's Beijing. The Ming dynasty (1368-1644) also committed large resources to canal maintenance and construction, keeping the canal clear so that ocean transport was not required for grain distribution. The Qing dynasty (1644-1911) synthesised the experience of previous dynasties and made canal maintenance a priority, thereby ensuring the prosperity and development of the cities along the canal and the success of the southern expeditions of the Kangxi and Qianlong emperors (see 'The Southern Expeditions of Emperors Kangxi and Qianlong', in the Features section of this issue of China Heritage Quarterly). However, by the 19th century, the Grand Canal, like the Qing dynasty, had fallen into utter decline. A fatal blow was dealt to the canal by a massive flood of 1855 which resulted in the Yellow River changing its course and entering the sea in Shandong province. Moreover, sedimentation had gradually raised the level of the Yellow River above the surrounding plain, and it was not possible for the canal to cross under the river. The northern and southern sections of the canal were effectively separated, and fell into decline. The development of a railway network over the subsequent century ensured that the canal fell into ever increasing neglect. 5. 1949-1984In 1949, the Communist victors in China's civil war inherited the Grand Canal at a time when large-scale engineering projects were regarded as testimonies to social advancement. Chinese engineers looked with enthusiasm to the day when the Grand Canal could be restored after a century of decay and neglect and rank among the world's great waterways–Panama and Suez, the St. Lawrence Seaway and Stalin's canal network that, with rivers, effectively linked the Baltic, White and Black seas. The new Chinese government set about clearing unexploded ordnance from the bridges, locks and dykes, a legacy of the civil war in which Chiang Kai-shek had no compunction in including flooding in his arsenal for warfare. There were many reports in the Chinese press of explosions occurring along the Grand Canal during 1949 and 1950, but by the end of 1950 most landmines and bombs had been cleared away.  Fig.13 Photograph of a modern lock at Suqian. Source: Zhongguo wenhua yichan, 2006:1, p.18.  Fig.14 Jiangsu (Xuzhou) stretch of the Grand Canal Source: Fu Chonglan, Zhongguo yunhe zhuan, n.p. In 1958, the Chinese government announced a major plan to dredge and revive the Grand Canal. Transportation and irrigation, as well as flood mitigation and prevention, were all targets within the sights of the project's engineers, and offices to coordinate the massive dredging and construction projects were set up in each province along its length. (Fig.13) Farmers, workers, clerks, students and soldiers were all dragooned into voluntary work between 1958 and 1961 to realise this grand plan, part of the Great Leap Forward, an enterprise which must have come at great human cost during this period now acknowledged to have ushered in famine and starvation. Nearly 160 million cubic metres of earth were excavated during these three years, but only 3.7 million cubic metres of this massive amount was shifted by machine. During this period seven major locks–at Xietai, Liushan, Siyang, Huaiyin, Huai'an, Shaobo and Shiqiao-were completed, and three major coal ports were constructed – at Wanzhai, Shuanglou and Pixian. A large railway bridge spanning the canal was constructed in Xuzhou, as were highway bridges across the canal at Xuzhou, Huaiyin and Yangzhou (Fig.14). In Shandong a large lock was constructed serving the four lakes collectively called Weishan lake. This afforded passage of the canal across the lake's 140 km from north to south. A large bridge also spanning the Grand Canal was constructed in Jining, Shandong province. Many of the achievements of the gargantuan efforts and labours of these years fell again into neglect with the Cultural Revolution and its aftermath. 6. Post-1984 Fig.15 Early photograph of the road alongside the canal in the Muslim village of Tianmucun near Tianjin (photograph in the collection of Dong Yongwei). Source: An Zuozhang, Zhongguo yunhe wenhua shi, 2001, v.1, n.p. A revival of the Grand Canal began in 1984, according to Fu Chonglan, who has been a passionate observer of the canal over the past two decades,[2] when state planners sought to revive the neglected and rundown canal with massive planning and investments, again targeting the various tasks the canal was intended to address, ranging from transportation to flood relief. In 1985, this work focused on the stretches of the canal south of the Yellow River from Jining to Yangzhou, and the sections of the canal south of the Yangtze from Zhejiang to Hangzhou. Much of the canal between Tianjin and Dezhou had ceased to flow, and sections of the canal had been cut between Beijing and Tianjin. (Fig.15) The Grand Canal is basically now only navigable without interruption from Jining southwards to Hangzhou. Unlike many conservators, Fu Chonglan argues that, if the Grand Canal is a central component in the massive project to bring water from southern China to the nation's dry north, best known as the South-North Water Transfer (SNWT) Project, its future is rosy. The Background to Grand Canal ConservationOnly in the 1990s did the heritage value of the ancient canal complex receive media attention, although Luo Zhewen, better known for his championing of the Great Wall of China as a world heritage site (see 'Dedicated to Great Wall conservation: A portrait of three Chinese scholars', China Heritage Quarterly, no.6, June 2006), was arguing for the conservation of the Grand Canal twenty years ago. In December 2005, Luo Zhewen, Zheng Xiaoxie and Zhu Bingren published an open letter addressed to the mayors of 18 historical cities and towns along the Grand Canal, proposing that work be accelerated on applying for a heritage listing, and at the 2006 meetings in Beijing of the CPPCC a petition of 58 representatives called for the lodging of an application for world heritage listing of the Grand Canal. On 12 May 2006, an investigative team of CPPCC members and specialists in the fields of water conservancy, historical geography and cultural heritage preservation travelled to Beijing, Tianjin and four provinces to agitate for the drafting of a bid for world heritage listing of the canal. The major dilemma facing those who advocate such a listing is that UNESCO is unlikely to inscribe a site where dramatic damage and rampant development continues to take place, while the advocates of cultural heritage preservation argue that a listing is first required to enlist public attention for the cause.  Fig.16 Scene of Tongzhou. Source: Mingxinpian: Qingmo Zhongguo (Late-Qing China in post cards), Beijing: Zhongguo Renmin Daxue Chubanshe, 2004, p.120.  Fig.17 Photograph of one of the last baiduchuan ferry boats plying the Grand Canal in Wuxi. There is no possibility that the Grand Canal could ever be returned to the pristine state that could only have ever existed in picture postcards. (Figs.16&17) Hydraulic engineers, however, envisage that if the Eastern Route of the South-North Water Transfer (SNWT) Project utilises 90% of the Grand Canal, then damage to the canal will be minimised and less farmland lost. The first phase of construction of the Eastern Route is underway, but because the Dezhou section of the Grand Canal in Shandong is basically a canal removing waste water from the petrochemical plants and paper mills of Dezhou, this water will now go downstream to pollute the section of the Grand Canal at Cangzhou. Pollution is a major obstacle besetting any plans to revive the Grand Canal as a continuous part of the SNWT Project. Because the section of the Grand Canal between Dezhou and Tianjin was cut in the 1960s, water conservancy experts estimate that 300-400 million cubic litres of water will be required annually to restore and maintain just this section of the canal. The SNWT Project planners envisage bringing water from the Yangtze River northwards, but the waters in the source area in Yangzhou are also intensely polluted and the purification of this water to supply Tianjin's needs will be immensely expensive. Because of the pollution of water from these sources, Beijing and Tianjin are proposing that the SNWT Project brings water to them from the Danjiangkou reservoir on the upper reaches of the Hanjiang river along a Central Route that avoids the Grand Canal. If this latter proposal goes ahead, the dream of restoring the stretch of the Grand Canal between Dezhou and Tianjin will never be realised. Apart from the problems posed by pollution, the prohibitive electricity costs incurred in raising water to higher levels in the stretch of the Grand Canal through Jiangsu province also threatens to derail plans to fully restore the Grand Canal along its entire route as part of the SNWT Project. There is little water in the canal north beyond Jining in Shandong and little traffic, so once again the question emerges: Who will foot the enormous electricity bill of simply ensuring that water flows once again for the entire length of the Grand Canal? Members of the CPPCC-led investigative team were dismayed by the problems posed by water pollution, and argued that a national body be established to monitor pollution along the Grand Canal and coordinate its elimination and the revitalisation of water supplies. Another major obstacle to nominating the Grand Canal for world heritage listing is the lack of any sense of common ownership and shared heritage among officials from the various urban centres through which the canal runs. To date, few collective nominations of cultural heritage properties have been successful in China, where regional competitiveness obstructs cooperation. Heritage Efforts to DateMany local governments feel that funding for issues related to the SNWT Project, including heritage issues, should be the financial responsibility of the central government. Although the state has a preservation plan for underground archaeological sites that lie in the way of floodwaters from the project (see 'South-to-North Water Diversion', China Heritage Newsletter, no. 1, March, 2005), the few remaining heritage landscapes along the canal are not yet within the sights of the State Administration of Cultural Heritage. Uniting six provincial-level governments and an army of local authorities to prepare a joint bid is no easy matter. This will also require cooperation between the central government ministries in charge of water resources, construction, transportation and cultural relics. One of the Chinese vice-chairmen of the International Council on Monuments and Sites, Guo Zhan, has suggested that a national-level committee be set up to handle the preparation of a bid. There has also been fierce competition between cities and towns regarding their Grand Canal heritage. As well as compiling lists of cultural relic sites, classificatory schema for moveable cultural relics, potential world cultural and natural heritage sites, and lists of tangible and intangible cultural heritage items, the State Administration of Cultural Heritage has also compiled preliminary lists of ancient cities and ancient capital cities. Provinces, cities and counties compete to be included on these lists with all the assiduity of French restaurants vying for a rating in the Michelin Guide. It is difficult to see how the towns and cities that line the Grand Canal can conform to UNESCO criteria that call for ancient sites to have authenticity and integrity. Some have attacked the notion of cultural heritage purveyed by the UNESCO as outmoded. Others ask who will foot the bill for preserving tiny enclaves of traditional, but sub-standard, housing along the shores of the Grand Canal. Only heritage landscapes that juxtapose modern industrial and ancient sites authentically truly capture the Grand Canal as a working transport hub, particularly if the Eastern Route of the SNWT Project goes ahead. The Grand Canal remains a transport system, above all, and the fact that it is a working system sets it apart from other Chinese heritage sites. Heritage and tourism remain ancillary to the need expressed by most planners to improve the canal as a transport route. The integration of the Grand Canal with the South-North Water projects has also marked out for the Grand Canal as a unique cultural heritage area facing heightened threats. Chinese heritage planners have been mindful of how a number of European countries, notably the UK and France, have handled and packaged their canal heritages. The British have been extremely successful in their developing tourism within the context of their heritage, one which documents the Industrial Revolution and the engineering powerhouse that was 19th century England. But the Chinese canal heritage has more in common with that of France where the major canals were constructed in the 18th century, when the movement of grain and other agricultural produce was a paramount concern. The barges of the Sun King and the Qianlong Emperor serve as links between the canal cultures of these two agricultural nations during their ages of rising imperial prosperity.  Fig.18 Photograph of scene in Wuzhen village, Tongxiang township, Zhejiang province. Wuzhen is one of six ancient canal towns on the western side of the Grand Canal. Source: Photograph by Li Dihua, published in Zhongguo wenhua yichan, 2006:1, p.41.  Fig.19 Scene of the Zhejiang canal town of Zhouzhuang. Source: Mingxinpian: Qingmo Zhongguo, 2004, p.59. When the CPPCC's investigative team visited Hangzhou in 2006, Hangzhou Daily called a press conference at which Luo Zhewen suggested that Hangzhou should take the lead in nominating the Grand Canal as a world heritage property, and in May, the team issued the Hangzhou Declaration Calling for the Protection and Listing of the Grand Canal. Yangzhou and Hangzhou are two Grand Canal cities that have put great effort into preserving and developing their Grand Canal sites, as have a number of other southern canal towns and cities which do not technically line the Grand Canal as such but certainly form part of the Grand Canal's extended 'cultural landscape' (wenhua jingguan). The latter include Zhouzhuang, Tongli, Wuzhen, Shaoxing and Huzhou. (Figs.18&19) Over the past two years, a number of advocates of cultural heritage have also invoked the success of Shaoxing in the conservation of an environment criss-crossed by canals, and some writers now, surprisingly, cite 'the Shaoxing model'. However, for the time being, conservation efforts along the Grand Canal have stressed the immediacy of conducting archaeological excavations preceding the construction of the SNWT Project, the preservation of key sites, the organisation of Grand Canal tourism festivals (Liaocheng and Tongzhou) and the construction of museums and tourist centres in some Grand Canal cities (Yangzhou, Hangzhou, Wuxi, Zaozhuang, Liaocheng and Tongzhou).  Fig.20 Aerial photograph of the Hangzhou Grand Canal Museum, opened in October 2006, courtesy of: www.hangzhou.gov.cn.  Fig.21 Central courtyard of the new Hangzhou Grand Canal Museum.  Fig.22 Plaque of the new Hangzhou Grand Canal Museum. Hangzhou's Grand Canal Museum (Figs.20, 21&22) was inaugurated in October 2006, and while the Grand Canal museums in Liaocheng, Shandong province, and in Tongzhou, Beijing, are complete they are not yet open to the public, although visits can be arranged by appointment. The design of the Grand Canal Museum in Liaocheng (Fig.23) is inspired by the keel of a grain barge, while the museum in Tongzhou is a recreation of an ancient fixed 'stone barge' (shifang). On 15-16 October 2006, Beijing's Tongzhou government and the Beijing Municipal Administration of Cultural Heritage organised the Grand Canal of China Cultural Festival to highlight the work being undertaken in preservation and applying for the listing of Grand Canal heritage.  Fig.23 Exterior of newly opened Grand Canal Culture Museum in Liaocheng, Shandong province. The 2007 Press ConferenceOn 11 March 2007, a press conference on the theme of Grand Canal conservation and the preparation of its world heritage bid was held in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing. Chairing the meeting were four CPPCC members—Shan Jixiang, Liu Feng, Shu Yi and Liu Qingzhu. Shan Jixiang and Liu Feng spoke first. The major problems confronting conservation advocates became clear as the press conference wore on. Shan Jixiang, director of the State Administration of Cultural Heritage, outlined the complexity of defining the nature and scope of the Grand Canal as a comprehensive cultural heritage property:

Throughout his address he urged caution in tackling the conservation issues surrounding the canal. Although the Grand Canal was only listed as a national key cultural relic in 2005, he was critical of much of the rushed conservation work carried out since then, often intended to turn towns along the canal into overnight tourist destinations. He was critical of cities that had damaged the ancient appearance of areas lining the banks of the Grand Canal with cement plazas and well-trimmed lawns. Shan drew attention to the many archaeological sites associated with the canal and called for a new systematic survey of these sites. He pointed out that most surface-sites of the Sui-Tang period had already disappeared by the end of the Ming dynasty, although many of these still lie below tens of metres of accumulated silt. Over recent years, archaeologists have excavated a number of Sui-Tang Grand Canal sites in Henan and Anhui. As well as archaeological sites of the ancient period, Shan Jixiang noted that preliminary surveys conducted more than a decade ago resulted in the compilation of a list of 654 heritage sites. 'Grand Canal cultural heritage sites', he explained, 'comprise, firstly, the engineering features of the canal itself—channels, retaining walls, wharves, locks, dykes and bridges. Secondly, there are sites related to the infrastructure of the canal, such as government offices, granaries, inns, hostels, guild halls, post stations and temples. Thirdly, there are the historical towns and markets that line the Grand Canal. Fourthly, there is the intangible cultural heritage, as it relates to the area generally and to the types of sites just named'. These exhaustive criteria will expand the inventory of heritage properties beyond the 654 listed cultural heritage sites, 109 of which are national-level listings. He also noted that nine cities along the canal have official state-level listings as 'famous historical and cultural cities' (lishi wenhua mingcheng). In reply to a question from journalists, Shu Yi, coincidentally also deputy-director of the China Museums' Association, clarified Shan's reference to 'early modern' (jindai) and 'modern' (xiandai) heritage sites, by pointing out that many factories built both before and after 1949 were also being considered for heritage listings. In his address, Liu Feng provided an encapsulation of conservation efforts and publicity conducted by CPPCC members over the previous year, and singled out Hangzhou for taking the lead in conservation work among Grand Canal cities. 'I have just come from Hangzhou', Liu told journalists, 'There, the first stage of work on the conservation of the Grand Canal within the city is completed, and it is already the city's second most popular scenic attraction after the West Lake. RMB 5.6 million yuan has now been earmarked for the second stage of conservation work'. The press conference revealed that the main area of contention regarding the future of Grand Canal conservation efforts concerned the use of the SNWT Project to revive the Grand Canal from Jining northwards. Many conservationists want to see the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal navigable again for its entire length, and believe that the SNWT project could serve to revive the canal. Shan Jixiang is opposed outright to this much discussed proposal. Shu Yi pointed out that only if all water pollution problems were resolved along the entire length of the canal would it be feasible to bring in water from the SNWT Project and restore the old canal route. He noted that it is also hard to argue the merits of restoring a non-working canal; grain was transported originally along the canal from Jining to Beijing, but this is no longer required. However, Liu Qingzhu, head of the Academic Committee of the Institute of Archaeology under the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, pointed out that the use of the Grand Canal as an eastern distribution channel for the SNWT project would serve as a flood mitigation measure. Moreover, a revived northern canal would undoubtedly also attract massive tourist development. Aside from engineering problems associated with the SNWT Project, the main obstacles faced by advocates of Grand Canal conservation are legal and financial. Shan announced that a national body would be set up later this year to better protect the canal and prepare for its candidature as a world heritage site, but Shan and Liu both explained that one of the major delays in drafting legislation is conducting a comprehensive survey of the area to be protected and determining ownership issues. The budgets for cultural heritage work are expanding in China, but they cannot keep up with the demand. Understandably, Shan Jixiang was unable to put a figure on the cost of conserving the Grand Canal. He told journalists that when he assumed the directorship of SACH four years ago, 'the state gave us RMB 250 million annually, but this year the figure will reach RMB 1,250 million'. He estimated that municipal authorities in cities along the Grand Canal had spent a sum well in excess of that amount on conservation-related work in 2006. 'Preparing the application for a world heritage listing will be a long haul', Liu Feng said, 'and there will be many more problems than we can even envisage along the way'. [BGD/ © Bruce Gordon Doar] Notes:[1] Karl Wittfogel, Oriental Despotism: A Comparative Study of Total Power, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1957. [2] Fu Chonglan, The Story of the Grand Canal of China (Zhongguo yunhe zhuan), Taiyuan: Shanxi Renmin Chubanshe, 2005. |