|

||||||||

|

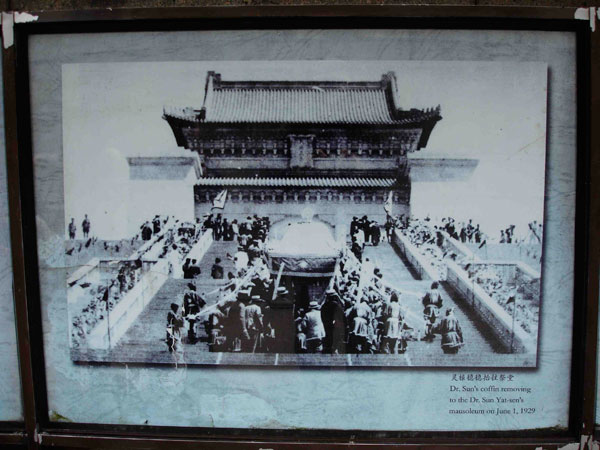

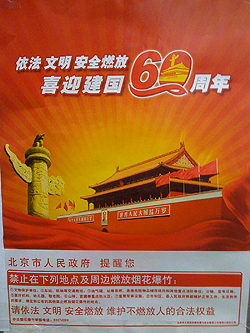

EDITORIALNo. 17, March 2009The Heritage of CommemorationHistory may not repeat itself, but it does rhyme a lot Remembering involves acts of forgetting, conscious and unconscious decisions to keep in the past things that were once in the present. It is said that in Hades the pool of Mnemosyne (rememberance), overseen by the goddess of the same name, was not far from the river Lethe, whose waters obliterated all memory. Acts of commemoration also involve a selective process whereby the individual, group or nation-state may banish from the mind's eye those events and people that once confronted it. Still, the lingering presence of memories thus elided, edited out or simply forgotten, can continue to haunt and disturb. The complex of edited memories, be they individual, collective or national, allow nonetheless for coherent narratives that make sense of lives, countries and whole eras. They can also constitute an arrant distortion that, while making the present easier to cope with, forestall other possibilities. The distillation and retelling of events past offer a mythology for those who live today and would persist blithely into the future. During the 'history wars' in Australia that stretched out for a decade from the mid 1990s, historians who brought to light through their research unpalatable truths about the ugly colonisation of the country and the devastation of its indigenous population were condemned by government leaders, right-wing media comentators and some others who claimed objectivity. These concerned historians were derided for promoting a 'black armband' view of the past. Their historical perspective, one which by its very nature encouraged a mournful recognition of a complex history of settlement and thoughtful reflection on its impact on the present, was seen as being a threat to national cohesion and uplifting narratives of progress and modernity. The powerholders and their media supporters were in turn chided for championing a 'white blindfold' view of the national story. In China, the blindfold is of a crimson hue. The year 2009 is one replete with commemorative moments for China. Some of the dates or eras remembered this year enjoy a near-universal currency. They resonate both in the People's Republic and internationally. Then there are episodes that invite sombre reflection; others still incite contentious debate and, even now, outspoken protest. This issue of China Heritage Quarterly offers, in a modest way, a consideration of some of the events and issues that are not included in the limited peripheral vision of the official retrospective. The most clamorous celebrations in 2009 will revolve around the ninetieth anniversary of the May Fourth demonstration at Tiananmen Gate in 1919, and the founding of the People's Republic of China at a ceremony officiated over by Mao Zedong from the podium atop Tiananmen itself thirty years later on 1 October 1949. In Features, Xu Jilin, a prominent intellectual historian based in Shanghai, reflects on May Fourth and comments on the changing patterns of marking this important anniversary. We also offer a retrospective on the ways in which China's 1 October National Day has been celebrated since 1949. 'Dark anniversaries' that are not so easily faced up to in the official calendar are also considered in this section, and we offer the reprint of an article entitled 'Confession, Redemption and Death'. In Articles, Jeremy Taylor presents his views on how Taiwan's Nationalist (KMT) heritage is considered and how the political present reconnects to that unsettling past. In New Scholarship, we are delighted to present work by two ANU colleagues. One relates to a project being undertaken by Duncan Campbell on the literary resonances of the Orchid Pavilion (Lanting 蘭亭), the other by John Minford to Bannerman (qiren 旗人) culture in the mid-Qing era (1790s-1840s). We also offer a report on a March 2009 conference held at the Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore on the Qing-dynasty emperor Kangxi. Articles on 'New Sinology' published in previous issue can now be read via a link on the homepage of the China Heritage Project. See http://rspas.anu.edu.au/pah/chinaheritageproject/newsinology/. This issue of China Heritage Quarterly is produced under the aegis of Geremie R. Barmé’s Australian Research Council-funded Federation Fellowship, the theme of which is ‘Beijing Spectacle’. The editor would like to thank Jude Shanahan and Karina Pelling for working to redesign the appearance of the e-journal, and for Jude's tireless work in laying out the Quarterly. I am also grateful to Dane Alston and Oanh Collins for scanning images and texts and Darren Boyd for editing and converting the film clips. Nora Chang of the Long Bow Archive in Boston has provided some of the the moving and still images that enliven these virtual pages. Lois Conner has kindly given us permission to use (and tint) her photograph of the Hua Biao at the eastern entrance of Peking University made in the winter of 1998 with the editor. The columns were removed to their present location from the ruins of the Ancestral Hall (Hongci Yonghu 鴻慈永祜) at the nearby Garden of Perfect Brightness in the 1920s. Anniversaries in the light, and in the darkGeremie R. BarméCommentators both in and outside of China have observed that 2009, as the sixtieth anniversary of New China, sees the completion of one cycle of the traditional Chinese calendar. The sexagenary cycle is known by the shorthand expression jiazi after the first year in the sequence. The jiazi is often connoted to mean a full lifespan or a revolution in time. Some argue that the year 2009 will thus prove to be a watershed year for the People’s Republic of China, both an end and, in some senses, a new beginning. The Chinese calendar offers other ways of marking significant moments of commemoration, or calamity, that are similarly at variance with Western custom. The years Bingwu and Dingwei, or Bing-Ding for short, also part of the sixty-year cycle, belong to the element of fire. It is said that disaster always ensues when these two years occur. In The Portents of Bing and Ding (Bingding guijian 丙丁龟鉴) by the twelfth-century writer Chai Wang 柴望, it is recorded that either natural or man-made disasters had occurred twenty-one times during the years Bingwu and Dingwei. The translator and essayist Yang Jiang noted that the last Bing-Ding years were 1966-68, when China was overwhelmed by the man-made ruction of the Cultural Revolution. It is for this reason that she named part of her Cultural Revolution memoir A Record of Bing-Ding (Bingding jishi, see my translation in Lost in the Crowd, Melbourne: McPhee Gribble, 1989, pp.11-52). The next Bing-Ding years come around in 2026-28. Regardless of the calendar one observes, for China the year 2009 is, nontheless, one of weighty remembrance. The major party-state anniversary of 1 October marks the sixtieth year since the founding of the People's Republic of China. On the 1 October 2009 National Day will be celebrated with a mass parade through Tiananmen Square and a lavish pyrotechnical display at night (see 'Thirteen National Days, a retrospective' in the Features section of this issue).  Fig. 1 The Monument to the People's Heroes, Tiananmen Square, 1989. [Photo: Luke Slattery. From New Ghosts, Old Dreams, p.329] The style and scale of such 'spectacles of Beijing', that is the major celebrations—or daqing 大庆 that have been a feature of China's National Day in 1959, 1969, 1984 and 1999—have reflected the changing priorities and political narrative of the Party-state. This year will be no different. There have, however, been two exceptions. The celebrations of 1979, the thirtieth since the founding of New China, were a muted affair. After all, they came shortly after the formal end of the Cultural Revolution (which is dated variously from the demise of Mao Zedong and the arrest of the 'Gang of Four' in 1976, or the Third Plenum of the Eighth Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party in late 1978). No grand parade of military and mass might was organised for Tiananmen that year. Instead, celebrations were held over until 1984, the thirty-fifth anniversary of the People's Republic. Fortuitously, although by no means accidentally, it was also the eightieth birthday of Deng Xiaoping, the man lauded as the 'grand architect' of China's opening up and reform process. The thirtieth anniversary of that transformative policy shift was duly celebrated during 2008, just as the Global Financial Crisis swept the world, including the People's Republic. Similarly, the fateful year of 1989 saw the 1 October National Day pass by with relatively little fanfare, in no small part due to the fact that much of the capital was still under martial law following the forceable occupation of the city by the People's Liberation Army in June. The year 2009 also marks other significant anniversaries. Some of these will be commemorated with due pomp and circumstance in the official media and dissected at length by learned gatherings. Others—those events best thought of as 'dark anniversaries'—will pass by in an atmosphere of heightened alertness, security crackdowns and official anxiety. These dark anniversaries are the silent markers of quelled protests, social unrest and state violence: events like those of 1959 in Lhasa, the closing down of the Xidan Democracy Wall in 1979, the tragedy of 1989 and the religious repression of 1999. They all offer other stories, and a contentious heritage, that play their own role in the unsteady growth of the strong unitary modern state. (See, for example, 'Confession, Redemption and Death' in the Features section of this issue). These years and the days within them offer a penumbra of history; they stand in shaded contrast to the vaunted moments of commemoration, those anniversaries which bask in the merciless glare of publicity and enjoy official largesse. Although formally ignored, or recalled only in verso, dark anniversaries cast a gloomy shadow over the orchestrated son et lumière of state occasions. The Doppelgängers of these dead anniversaries haunt the living.  Fig. 2 'It's been seventy years!' A slogan carried during the May 1989 demonstrations in Tiananmen Square. [Photo: Dajun, from New Ghosts, Old Dreams, p.347] Ninety years ago, and three decades before the founding of the People's Republic of China, on 4 May 1919, the space in front of Tiananmen Gate in Beijing was a rallying point for another purpose. On that day, students from Peking University gathered to protest, both against foreign aggression but also in favour of what student leaders at the time called Chinese 'cosmopolitanism'. The May Fourth Movement, as this moment—and the epoch-marking era of engaged protest and agitation for social and political change—would be known, is now hailed as a turning-point in modern Chinese history, one that signifies the awakening of the masses and their political radicalisation. Thoughtful scholars in China who have studied the historical record carefully, however, offer a more complex account. They identify in the May Fourth a strain of thought and activism that is centred on China becoming an optimistic and constructive actor in the world community, a community only recently devastated by the horrors and violence of the Great War in Europe. Although China itself would fall victim to the carve up of territories and rights ordained by the Versailles Peace Treaty in 1919, Chinese activists were then looking beyond the narrow self-interest of the Western imperial powers and the aggressive expansionism of the Empire of Japan (itself a newly assertive imperial power) to a more hopeful, and inclusive, future. These young intellectuals appealed to their comrades and encouraged their fellow citizens. They hoped that a modern, newly democratic, although faltering China could pursue its compact with the nascent international community. In the intellectual tradition of such thinkers as Liang Qichao and Yang Du, they were agitating in favour of China being a 'nation committed to cosmopolitanism', and not just a narrowly self-concerned 'nation-state' that in a Darwinian world concerned solely with the survival of the fittest would find itself in constant avaricious competition with other nations. They looked beyond the limits of the nation-state, the pitfalls of which had led Europe into such devastating self-cannibalisation. As China itself pursued a course towards modernity, one in which social justice and equality would feature, and not just material acquisition and trade competition, they appealed to their countrymen and women to aspire to higher goals. The late-Qing thinker Yang Du in particular argued that China as a polity, and as a community of thinking people, had to slough off the traditional worldview expressed in the ancient Confucian term 'tianxia' or All-Under-Heaven in favour of becoming a 'cosmopolitan nation'. That was, China should be a modernising nation that did not try to conceptualise its place in the world according to a re-jigged traditional mindset that still placed itself at the centre of a hierarchic ordering of society and 'All-Under-Heaven'. For, to do so might appeal to an underlying cultural assertiveness common in the Chinese popular and political imagination, but equally it could too readily evoke a kind of populist authoritarianism that threatened dire consequences for the country's future. That is not to say that Yang Du was not in favour of a strong state. As the promoter of 'Gold-and-Iron-ism' (jintiezhuyi) Yang famously argued that it was primarily on the basis of material wealth and the strength of arms that China could assert itself as a modern nation. Patriotism and protectionism evolved in China from the late-nineteenth century in tandem with that nation's transformation from imperial dynasty into modern nation-state. As was the fate of other nation-states under the influence of various strains of political thought and social Darwinism, that of China would be one in which the strains of national identity, the sense of embattlement, and the requirements of political radicalisation—all brought into focus and exacerbated by heedless trade and imperial aggression from the outside world—would serve to distort a more benign patriotism into a form of rabid nationalism. The late-Qing thinker and activist Kang Youwei was famous for re-defining another ancient Confucian term to describe the future of humankind. He favoured social and national progress that would see the realization of a 'Great Harmony' (datong), one in which social divisions, material inequalities and national differences would give way to a Utopia. Kang's fellow political activist and reformer Liang Qichao despaired of the role that Europe could play in advancing the interests of humankind after the atavism of the Great War. He travelled through Europe and witnessed for himself the devastating consequences of narrow nationalism and imperial competition. Writing ninety years ago, Liang said that even in the ruins of the post-War world there could, and should, be a reconciliation between the ideal of a 'cosmopolitan nation' and the 'nation-state': Our nationalism is one in which there is both the country and the individual; one in which there is both the country and the world. While we place ourselves under the protection of a specific nation, we should hope that the natural-given talents of every individual in the nation can achieve the greatest realisation so that the greatest possible contribution can be made to the betterment of global civilisation. The resources of a broad humanity, and expressions of interest in, empathy for and a model of action to engage with the shared human situation can be found in other Chinese articulations. When writing about the seventieth anniversary of the May Fourth Movement (see 'The May Fourth Spirit, Now and Then' in the Features section of this issue) two decades ago, the Shanghai-based intellectual historian Xu Jilin noted the changing rhetorical landscape of the May Fourth from 1929 to 1989. In early 2009, Xu composed another essay to mark May Fourth. To appear in the leading Beijing journal Reading (Dushu) on the eve of 4 May 2009, Xu's essay 'Historical Memories of the May Fourth', translated here by Duncan Campbell, appears in the Features section of this issue of China Heritage Quarterly as a 'pre-publication' of the Chinese original.  Fig. 3 'Rebirth' [From New Ghosts, Old Dreams] As an historian of modern China and as an engaged member of the lively, and often rancorous, intellectual community of thinkers and writers living in the People's Republic, Xu Jilin is acutely aware of the clashing histories and legacies of the May Fourth Movement. In his new essay Xu powerfully contrasts the contending traditions of patriotism within China and, in effect, speaks to the new tide of globalised Chinese nationalism that reached a crescendo during the March-April 2008 worldwide protests during the Olympic Torch Relay. In 2008, some writers who have carved out an intellectual and market niche for themselves as inheritors of the virulent strain of nationalism that had such baleful effects in China's twentieth century, propounded what they dubbed a 'new worldism' (xin shijiezhuyi). Quite unlike the 'cosmopolitanism' of the 1910s of which Xu Jilin writes, this 'new worldism' is celebrated by polemicists like Gan Yang (a man self-described as an 'independent leftist'). He declared that the 19 April 2008 demonstrations of Chinese patriots against pro-Tibet and pro-human rights demonstrators surpassed the May Fourth as a mass patriotic movement played out on a vast international stage. Intellectual jingoists like Gan Yang celebrated such global agitation as marking new age of national awakening, one that foreshadows the rise of a confident China. They argue that through a principled and steadfast engagement with the world community China can evince economic, military and cultural strength of a kind that can help it face down its opponents, as well as the distorting 'Western media'.[1] Given the oratorical landscape of Sinophone writings, one in which rhetorical violence, feverish overstatement and the soapbox forge an alluring troika, such blithe braggadocio comes all too easily. For thinkers like Xu Jilin the other tradition of May Fourth has a more pressing relevance, and allure. He reminds his readers that that earlier tide of nationalism eventually inundated the country and drowned out for many decades the measured voices of reason and humanity. The cosmopolitanism of the May Fourth patriotism is as vital today as it was in those early post-War years. Ninety years ago socially aware and political active individuals saw the possible dawning of a 'new century' and a 'new age'. As Xu Jilin points out, the Peking University Student Weekly established in 1920 stated in its editorial announcement that, 'China is but a unit within the world.... Thus we should declare, "We reject those things that benefit but one nation and not the world"'. Such sentiments reflected, and continue to reflect, an idealism all too easily forgotten in the competitive environment of nation states, the marketplace of ideas and the careerism of intellectual-nationalists. In recent years, what has been called a revived Tianxia System (Tianxia tixi) has enjoyed a particular purchase on Chinese discussions of international relations. This 'system' has been promoted by Zhao Tingyang, whose writings on the subject have enjoyed considerable popularity, and some influence, among the 'China School' of thinkers who debate China's rise on the international intellectual stage.[2] But as with many developments in other areas of academic work—among 'new left thinkers' and academic 'China-essence patriots'—issues of cultural sovereignty are confounded with academic discussion, and the inertia of exceptionalism mitigates against the very engagement that can bring the best of China's complex intellectual and cultural traditions into the mainstream. However, as William Callahan has observed, 'Zhao is interested in transcending this chaotic (and nationalist) intellectual scene by unifying the world of thought under the banner of the Tianxia system.'[3]  Fig. 4 The arrival of Sun Yat-sen's catafalque at the Zhongshan Ling presidential tomb outside Nanjing in June 1929. [From Zhongshan Ling photographic display, March 2009. Photo: GRB] Not all uses of tianxia (All-Under-Heaven) reflect such an unsettling pedigree. At times it has been used to give voice to broader concerns about the common weal. One thinks, for example of the eleventh-century Song-dynasty writer Fan Zhongyan who gave voice to one of the most elegant expressions of concern for the stability of his time and the benefit of the people he served. Writing in his famous Record on the Yueyang Pavilion (Yueyang Lou ji) he declared his desire 'to take the cares of the world ahead of all else, to rest only when others experience happiness' (xian tianxia zhi you er you, hou tianxia zhi le er le 先天下之憂而憂,後天下之樂而樂). Similar sentiments were expressed by the Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao who quoted Fan Zhongyan during his April 2006 state visit to Wellington in New Zealand.[4]  Chinese Spring Festival poster, Beijing, February 2009 [Photo: GRB] In modern terms such sentiments are used to express a shared human concern, one that in this age of global integration and interdependence reaches beyond the borders of specific nation-states, and hoary cultural traditions. There is increasing discussion in China not only of how re-formulated traditional tropes can serve the needs of the Party-state, but how 'universal values'—pushi jiazhi—their articulation, pursuit and preservation, can also help further China on its path to achieve a sustainable and mature modernity. Perhaps we can detect such a spirit enlivening Wen Jiabao's consideration of the challenges facing his government. (In this context, see 'Worrying China & New Sinology' in Issue 14, June 2008, of China Heritage Quarterly.) In April 2008, when answering a journalist's questions, Wen Jiabao quoted from the Biography of Wang Anshi in the Song History written by the Mongolian writer Mieliqi Tuotuo to the effect that, 'There is no need to fear changes in the heavenly way, no need to emulate the way of the ancestors, no need to seek the approval of others' (tian bian bu zu wei, zuzong bu zu fa, ren yan bu zu xu 天變不足畏,祖宗不足法,人言不足恤). Is there not some possibility that instead of China's 'peaceful evolution' it can participate in an 'harmonious evolution' into the international order to take a leading role in global affairs not underpinned by outbursts of aggrieved nationalism or slighted dignity, but on the bases of a greater assuredness? Some would argue that the dark anniversaries that linger in the shadows whenever the clamour celebrating state-ordained triumphs offer a guilty reminder of what has been suppressed, forgotten by fiat and negated. They also remind us of the other stories that are part of the complex of narratives informing the history of modern China. Perhaps at some far remove they will again fire the imagination of that country. Notes:[1] See Robert Ayson and Brendan Taylor, 'Carrying China's Torch', Survival, 50:4 (2008), pp.5-10; and my 'China's Flat Earth: History and 8 August 2008', The China Quarterly, 197, March 2009, pp.5-6.

[2] See, for example, Zhao Tingyang, Tianxia Tixi: Shijie zhidu zhexue daolun [The Tianxia system: A Philosophy for a World System], Nanjing: Jiangsu Jiaoyu Chubanshe, 2005. [3] William Callahan, 'Chinese Visions of World Order: Post-hegemonic or a New Hegemony?', International Studies Review, (2008) 10, pp.749–761, at p.758. [4] Wang Chunyong, Wen Jiabao zongli jingdian yinju jieshuo [Introduction to quotations from the classics employed by Premier Wen Jiabao], Hong Kong: Zhonghua Shuju, 2008, pp.18-20. |