|

||||||||

|

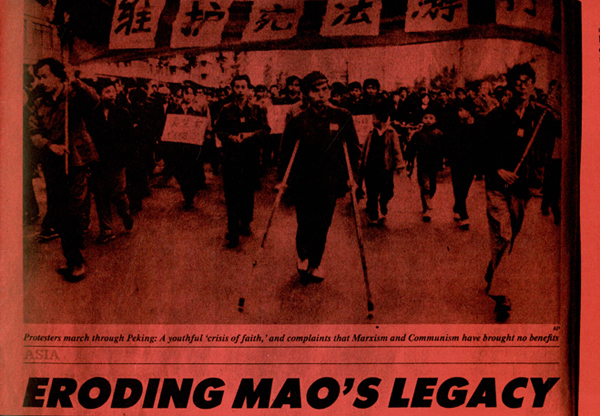

EDITORIALNo. 18, June 2009The Heritage of Commemoration, Part IIThis issue continues with a focus on commemoration. During 2009, in the media and within academic circles, both Chinese and international, there has already been widespread discussion of moments of historical significance in modern Chinese history. Much of the discussion has touched on the continuing reverberations of events and dates that have acquired an iconic significance. The remembrance of key moments in the past is important, as is the question of how these moments are variously turned into history, ossified and sculpted for practical and abstract exigencies. In this issue, our attention is on the living heritage of commemoration. That is, how the powerful historical periods, incidents and dates of the past live on in the present, in real lives and real situations. In particular we focus on 1919, 1949, 1959 and 1989. In this context, we are delighted that the intellectual historian Vera Schwarcz has written about her encounters in the Chinese capital during the May Fourth commemorations of 2009. We also feature a number of oral history interviews by Sang Ye related to 1949, 1959 and 1979 accompanied by visual and, in the case of 1959, audio-visual material. Qiang Zhai's translation of the Party elder Bo Yibo's account of how Mao Zedong responded to US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles strategy to encourage 'peaceful evolution' in the socialist bloc provides an important perspective on a policy stance that continues to have profound ramifications in China, and internationally, today. Excerpts from a hard-to-access documentary film forms the basis for the Feature '1969: April Fools' Day', while in considering the momentous events of twenty years ago and the long shadow they cast over the present we pick up on a discussion about 'totalitarian nostalgia' and the Chinese heritage of denunciation. We also carry the Long Bow Appeal that recalls the tragic events of 1989 and the persistent threats to free speech and independent academic inquiry, both outside and inside China. In Articles we introduce the work of the Beijing essayist Xu Zhiyuan and the young scholar Stephen McDowall, while in New Scholarship we report on the Wujing Project, offer an insightful review of a new biography of Confucius and, through translation, trace the remains of a number of China's great private libraries. I am grateful to Nora Chang of the Long Bow Group for providing crucial audio-visual material from the Long Bow Archive in Boston, to Oanh Collins for scanning visual materials, as well as to Janos Batten who proof-read much of text of the issue in draft form. I am as ever grateful to Jude Shanahan for her good humour and resilience when preparing this issue. Remaining errors and infelicities are my responsibility. Issue 19 of China Heritage Quarterly (September 2009) will take as its focus the heritage of 'T'ien-hsia', a term sometimes translated as 'All Under Heaven'. A number of further articles related to the commemorations of 2009 will also be carried in that issue. Living the HeritageGeremie R. BarméAs we reconsider the momentous events of the past that are being commemorated, or consciously repressed, during 2009, we are reminded of words from the Yi Jing 易經, the ancient text of divination: 'There is no going without a return' (wu wang er bu fu 無往而不復). In this issue we continue the theme of commemoration and its various heritages. The questions raised by this commemorative year are so numerous and complex that it seemed appropriate to devote further consideration to the legacies of years past as they resonate into the present and extend into the future. Herein we consider in particular the lived aspects of those commemorative years, that is the ways in which the past, for good and for ill, are experienced today. In our previous issue we spoke of the 'dark' and 'light' anniversaries of 2009. We observed of these contrasting moments that:

An Unresolved May FourthOur June issue featured Xu Jilin's considerations of some of the easily overlooked aspects of the original May Fourth era surrounding the momentous demonstration of 4 May 1919 (see Historical Memories of May Fourth). In this issue we offer a very personal reflection on this year's official commemorations of the May Fourth by Vera Schwarcz, a noted writer and intellectual historian who, through her work over some four decades, has travelled a personal journey back to and from China's May Fourth era, bringing it into closer conversation with the concerns of a broader humanity. In her essay, 'Re-conceiving and Un-learning May Fourth' (see the first piece in Features in this issue), Vera provides us with an overview of the more professional academic reconsiderations of May Fourth at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences on 3 May 2009, as well as an account of the state-orchestrated and po-faced celebration which she attended the following day. On the latter occasion the lacklustre and contested official line on the period was duly reiterated. As Vera observes, Mao's evaluation of May Fourth as given in 'On New Democracy' (January 1940) remains the regnant orthodoxy. Or, to quote the Chairman himself:

This political formulation served the Chinese Communist Party well as it claimed China's twentieth century history, and struggles, for itself. In recent decades, however, intellectual pluralism within China, and the continued scholarly efforts of international academics, have put the Maoist line into a historical perspective and challenged it. Vera Schwarcz's essay takes the reader into another realm, one both personal, but also powerfully relevant to an appreciation of serious non-academic considerations of May Fourth, its spirit and the contested legacies of twentieth-century Chinese intellectual and political history. In particular, she discusses her encounter with a young editor and writer for Life (Shenghuo 生活) magazine in Beijing, Zhang Quan 张泉. The broader, culturally and socially positive, possibilities of the commercial realm are often stifled by material avarice, but Vera's essay reminds us of the latitude that commercially active concerns like Life magazine provide for some writers. We are reminded also how, in China's marketplace of ideas, nuanced views, carefully modulated insights and perspicacity can confound the crude strictures of the Party-state to present the interested and engaged public (and not just the self-aggrandizing intelligenstia) with new perspectives on the heritage of their own lives.  Ten Years After the Stars. Book cover In this issue we offer an essay by another writer for Life, the Beijing-based author Xu Zhiyuan 许知远. Xu is an editor, writer and independent scholar whose fascination with Chinese thought is matched by his interest in the various trajectories of international academic work on Chinese history, and the various legacies of Sinology and Chinese Studies. Here, however, we offer a translation of a short essay collected in his book Chinese Affairs (see 'Trading on Heritage' in Articles in this issue). The Presence of the PastOn 4 May 2009, Xu published another essay, this time commemorating the May Fourth era. Entitled 'What's their Company Called?' (Tamen shi neijia gongside? 他们是哪家公司的?), the essay offers some personal reflections on that momentous period for modern Chinese intellectual, political and cultural history. He reminds readers of why the May Fourth era is still so vital; he observes that many of the issues articulated ninety years ago remain as pressingly relevant today as they were then. He indicates that the complex inheritance of China's twentieth century is not something bound to museum displays and dusty tomes, but rather it is part of a vivid and unsettling contemporary reality. In his 4 May essay, Xu wrote:

As Xu concludes, 'The thinking and actions of those individuals can inspire and uplift us. They can encourage us to continue their enterprise and to create a new heritage for future generations'. (For the original, see http://www.mindmeters.com/blogind.asp?id=16). If Xu's tone is lambent, although cautious, other writers like the historian Lin Xianzhi 林贤治 have offered a more strident cri de coeur when contemplating the fate of the May Fourth era (see Lin's 'The Death of May Fourth' Wusi zhi si 五四之死, written March-April 1999 and carried online on 30 April 2009). Then again, for the way May Fourth is seen by one lecturer at Xu Zhiyuan's alma mater today, see 'My PKU teacher's take on this May 4th'. U-turns Dramatic change and the promise of a new enlightenment featured in the sixtieth commemorative year of May Fourth in 1979. In the popular agitation that accompanied the Chinese Communist Party's new economic policies initiated in late 1978 a new cultural, intellectual and (stillborn) political efflorescence was evident in the nation's capital. In late September 1979, the Stars (Xingxing 星星), a group of dissenting avant-garde artists, held a gimcrack exhibition along the front perimeter of the China Art Gallery in central Beijing. Their works were overtly political and also emblematic of the 'Beijing Spring' that flourished for a short time in 1978-79. Their 'show' was shut down by the authorities and on the 1 October National Day the artists marched in protest against the repression of cultural self-expression. However, the spirit that informed non-official art would continue to enliven the Chinese cultural scene throughout the 1980s. Over time the Party-state evolved ever-new ways to engage with cultural difference and diversity. Although it remained ham-fisted in dealing with demands for broader social and political tolerance, non-official culture (art, film, poetry and fiction) came to enjoy previously unknown levels of tolerance, and in some cases support. Ten years after the Stars abortive exhibition and protests, in February 1989, the China Art Gallery hosted a retrospective exhibition of post-1978 art. Most of the work on display at a show simply titled 'Modern Chinese Art' was fairly staid, though there were a few more confronting pieces. At the time, aware of the efforts made during the Hu Yaobang-Zhao Ziyang era to coopt nonofficial cultural figures, I observed rather dyspeptically:

The Fujian artist Wu Shanzhuan 吴山专, formerly of Amoy Dada, summed up his feelings about the cultural bureaucracy, curators, agents, dealers and the cultural middlemen with an artistic his performance piece at the February 1989 exhibition. Entitled 'Big Business' he started selling prawns (then a luxury foodstuff) on the ground floor of the gallery. As it was reported in the main nonofficial artistic journal of the day, Fine Arts in China:

The trademark banner of the exhibition was a 'U-turns Prohibited' sign. Although Fine Arts in China was forced to cease publication as a result of the 1989 purge, from the early 1990s China's arts world would flourish in new and exciting ways, and by the new millennium the authorities, while maintaining control on political freedom, found more sophisticated ways to embrace the country's burgeoning, and highly profitable, 'creative cultural industries'. In this context, it is worth recalling the formal statement that Wu Shanzhuan released at the time that he was hawking his prawns in the China Art Gallery. It said in part:

Shooting dialogue, Xiao Lu, 5 February, 1989. Wu's act was a protest against the times, but it was also an unknowingly prescient comment on the future of Chinese art on the international bourse. Even more poignant was the installation 'Dialogue' (Duihua 对话) by Xiao Lu 肖鲁 and Tang Song 唐宋 and which featured two phone booths with people backs turned busy on the phone. On the morning of 5 February 1989, Xiao Lu shot two rounds into the work. Both artists were detained and the 'Modern Chinese Art' exhibition was shut down. In retrospect it was interpreted as being an incident foretelling the deaths of some of those who would demand an equitable dialogue with the government only a few months later. Mountain RedoubtsThe power, and problems, of commerce also feature in another commemorative moment that we mark in this issue. The July 1979 Huang Shan Talks (Huang Shan tanhua 黄山谈话) of Deng Xiaoping mark the transformation of China's tourist industry from being primarily a political enterprise into a business one. In Features we offer an oral history interview with Yang Zhiyuan 杨志远, a specialist in the history of the Chinese tourism. In his remarks, which are from a chapter in Sang Ye and Geremie R. Barmé's book The Rings of Beijing: Inside China's Olympic Aura, Yang offers insights into the history of Chinese tourism from 1949, through the establishment of the new China Travel Service and up to the time of Deng's crucial July 1979 speech at the mountain resort of Huang Shan 黄山 in Anhui 安徽. Another commemoration involves a different scenic mountain in China, Lu Shan 庐山 in Jiangxi 江西 province. It was here that an infamous gathering known as the Party's Lu Shan Conference (Lu Shan huiyi 庐山会议) took place in the summer months of 1959. The meeting was convened to discuss the progress of the Great Leap Forward policy. The early excesses of the Leap had alerted the leadership to the fact that utopian hopes and unrealistic policy settings had encouraged over-zealous local cadres to generate inflated statistics and to impose impossible demands on rural producers. The result was a catastrophic dislocation of the national economy, in particular the rural economy. At Lu Shan plans were being mooted to modulate these extreme policies, but events at the idyllic summer resort resulted in exactly the opposite. Peng Dehuai 彭德怀, the Minister of Defence, wrote a letter to Mao—what is usually referred to as a 'ten-thousand word petition to the throne' (wanyan shangshu 万言上书)—in which he reported on the unfolding disaster and called for a halt to the ruinous policies. Mao was affronted by Peng's petition and suspected that it disguised a widespread plot against him. As the memoirs of the Party elder Bo Yibo 薄一波 published in 1996 reveal (see Qian Zhai's translation in Features), Mao would link the US strategy of encouraging 'peaceful evolution' (translated in Chinese as heping yanbian 和平演变) in the socialist countries to Peng Dehuai's guileless plea on behalf of his suffering people. The results were immensely tragic (see '1959 & its Aftermath' in Features). The scale and significance of the man-made famine of the late 1950s and early 60s is still overlooked in mainstream Chinese accounts. Meanwhile, fear of 'peaceful evolution' continues to inform the political and social policies of the country's leaders. For his part, in 1989 Deng Xiaoping reaffirmed that China was in imminent danger of peacefully evolving into a 'bourgeois vassaldom' of the US and the Western trading nations. That was a decade after he made a historical trip to the United States at the dawn of the new era of China's Open Door and Reform policies. Time magazine even named him its Man of the Year for 1979. While he receive this accolade in China the first calls for political liberalisation were being suppressed, and on the country's southern borders a long and bloody conflict with a former ally, Vietnam, unfolded (see 'Three Decades After the Sino-Vietnamese War'). Deng Xiaoping's reputation as a reformer and a leader who, compared to many of his fellows had little blood on his hands, was seriously sullied by the violent end of the 1989 Protest Movement. Then, on the eve of the twentieth anniversary of that repression this year, the release of the ousted Party leader Zhao Ziyang's memoirs would change Deng's reputation forever. A New Anniversary and Another Coming OutThe mass Protest Movement of 1989 was an outpouring of popular discontent and frustration. From mid April to early June that year a lose coalition of demonstrators demanded various freedoms and rights, as well as the chance to express displeasure at the authorities for their unresponsive, corrupt and arrogant rule. As we all know, it ended in state-sanctioned mass murder. In 2009, while broader calls for civil rights were ignored by the authorities, a more colourful quest for diversity, recognition and equality proceeded. The 28 June 2009 marked the fortieth anniversary of the Stonewall riot in New York, a watershed event in what would become the GLBT movement. In China, from 7-13 June, Shanghai Pride marked the first mainstream gay event in China. A film festival was organised, as was a series of other cultural events. Official displeasure prevented a gay pride parade of the kind seen in cities around the world, and the usual policing and harassment dampened the cultural events. Despite this, one of the organisers, an American by the name of Tiffany Lemay remarked that '…last year, we saw the Beijing Olympics described as "China's coming out" party. Now China is really coming out—this time from the closet' (see Shanghai Pride). Sadly, the country's political 'coming out' is still some way off, a fact attested to by the formal arrest in June 2009 of the writer and thinker Liu Xiaobo for 'sedition'. The 'nines' will continued to be remembered in China be it with the reds of revolution and bloodshed, the white of mourning or the black of despair. From 2009, however, this palette will at least be added to by the colours of the rainbow.  Protesting members of the Stars group, 1 October, 1979. Source: Newsweek |