|

|||||||||

|

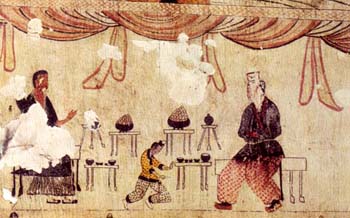

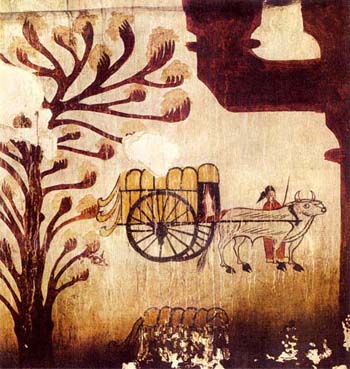

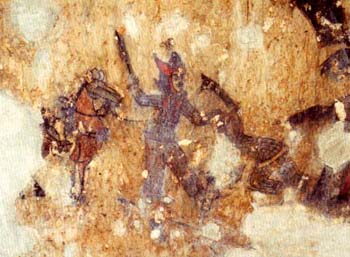

FEATURESShared Heritage Sites: The Mural Tombs of Gaogouli-KoguryoThe twenty-eighth session of UNESCO's World Heritage Committee, meeting in Suzhou in July 2004, inscribed the Gaogouli-Koguryo city and tomb sites of China, in what is today Ji'an city, Jilin province, as well as those in neighbouring Huanren county of Liaoning province, on the World Heritage list, and at the same time it also inscribed on that list 63 Koguryo heritage sites in the DPRK (North Korea). The tombs of this culture developed from earth or stone covered tumuli to attain the classic proportions of the largest Gaogouli-Koguryo (hereafter GK) tombs of the late period that resemble stone pyramids. One of the best preserved examples of the latter in China is the tomb in Ji'an known today as the General's Tomb (Jiangjun Fen).  Fig.1 Aerial view of the General's Tomb (Jiangjun Fen) located in the Yushan tomb district of Ji'an city, Jilin province. Many of the listed heritage tombs do, however, contain the vivid murals that document the unique culture of the GK people and their society. Despite the renown of these murals, very few GK tombs do in fact contain them. Gina Barnes writes that the fame of these mural tombs overshadows the fact that they account for less than 1 per cent of the known Koguryo tombs (66 out of approximately 10,000).[1] Since Gina Barnes made this estimate, the number of mural tombs has grown to around ninety today. The wall paintings were found only in the tombs of aristocrats and rulers, although some very large tombs, such as the General's Tomb, did not contain murals. Few of the tombs with murals can be classified as pyramid tombs and most were tumulus tombs. Most of the tomb mural sequences contain a portrait of the tomb occupant and genre illustrations depicting scenes from the life of the deceased. These include hunting scenes, processions, lavish entertainments and banqueting scenes, or more discrete figural scenes of the tomb owner and his wife being served food. Some of the best early portraits of the tomb occupant and his wife being served from the kitchen were found in the tomb known as the Dancers Tomb (Chinese: Wuyong, Korean: Muyong) located three kilometres north-east of Ji'an, in the Donggou cemetery on the southern side of the Juedi mural tomb. The tomb was described by Japanese archaeologists in 1937. It comprises a main chamber and two side chambers. In 1966, when the tombs in the Donggou cemetery in Ji'an were being catalogued and surveyed, this tomb was designated JYM458. It is dated to the mid-4th century. The serving scene shows the master and mistress seated on backless raised chairs and the food is being set on the master's side table by a male servant. Incense burners or braziers can be seen on other small tables.  Fig.2 View of the seated tomb owner and his wife seated facing each other in mural from the Wuyong Tomb in the Yushan tomb district of Ji'an city, Jilin province. In the Dancers Tomb, not surprisingly, there is a mural on the eastern wall of the tomb chamber depicting a group of male and female dancers.  Fig.3 Detail showing a row of dancers from the mural on the eastern wall of the Wuyong Tomb in the Yushan tomb district of Ji'an city, Jilin province. Particularly noteworthy is a scene of hunting on the western wall of the same tomb.  Fig.4 Scene of hunting from the western wall of Wuyong (Korean: Muyong) Tomb in the Yushan tomb district of Ji'an city, Jilin province.  Fig.5 Detail showing a parked ox cart from the hunting scene on the western wall of the Wuyong (Korean: Muyong) Tomb in the Yushan tomb district of Ji'an city, Jilin province. The murals in the Wuyong tomb are cleverly framed by painted representations of wooden columns supporting massive beams framing each wall of the tomb chamber, and these give the visitor the impression of being inside a structure with the walls opened up to reveal a world rendered more unearthly by the elaborate depiction of constellations and religious iconography that seem to fill the canopy of the ceiling and resemble the heavens. The depiction of warfare rarely appears in GK murals, but the Macao (Horse Trough) Tomb murals contain a scene interpreted to illustrate a soldier decapitating a prisoner of war.  Fig.6 Mural depicting a soldier decapitating a prisoner of war in the Macao Tomb near Ji'an. The GK murals were painted directly onto the surface of the stone which had been treated with a mixture of slaked lime (calcium hydroxide) and seaweed extract. Before all the moisture evaporated from the treated surface, charcoal was burned to produce carbon monoxide which prepared the surface for painting. The painters of the murals were required to work quickly and for the outlines they used black pigment that was oil-soot carbon produced by burning oil with ox hide or fish emulsion which has a low viscosity. An alternative method used by the painters was to draw the outlines with soot carbon. Hematite was used as a basic pigment to colour the outlines, pillars and tree branches. The colours used to produce the GK murals were not organic pigments, which is why the colours have remained vibrant for such a long time without oxidizing or changing. The use of pigments that would adhere permanently to the wall surface was assisted by ensuring that a section of an overlaid colour was always applied directly to the surface of the stone. This technique of adherence enabled some sections of the paint to be applied thickly, and the techniques developed by the GK tomb mural painters were later incorporated into Buddhist painting in Korea. Religious and cosmological iconography was a major feature of the GK tomb murals. Although the sources of the iconography were often drawn from Daoism, Buddhism or Chinese mythology, the figures were distinctly dressed in GK clothing that prefigured Korean dress of later periods. Two figures in a mural on the ceiling of Wukui (Korean: Ohoe) Tomb no. 5 in Ji'an have been interpreted to represent the deities of the moon and the sun (Korean: Ilwol-sin).  Fig.7 Figure of the moon deity (Nüwa) from a mural in Wukui Tomb no. 5, Ji'an city, Jilin province.  Fig.8 Figure of the sun deity (Fuxi) from a mural in Wukui Tomb no. 5, Ji'an city, Jilin province. The deities of the sun and moon are male and female, respectively. The female deity holds a disc representing the moon above her head while the male deity holds a sun disc containing a crow above his head. These murals are unusual because they feature raised black outlines which were later filled with colour. The scrolling floral motifs recall the baoxianghua ('honeysuckle') patterns taken from Buddhist pictorial art. Other less ethereal versions of the deities of the sun and moon appear in Wukei (Ohoe) Tomb no. 4.  Fig.9 Figure of the moon and sun deities (Nüwa and Fuxi) from a mural in Wukui Tomb no. 4, Ji'an city, Jilin province. In view of the reassessment of much ancient religious iconography in China in recent years, many of the deities and spirits in GK art, particularly those of the winged variety, have resonances with deities seen in the art of Dunhuang and beyond. It is less possible to discuss with confidence the iconography we encounter in ancient Chinese art today than it was twenty years ago. It is to be hoped that Korean and Chinese scholars can now assess the significance of the many masterpieces of GK art that is now part of shared heritage of humanity and interpret it in a new context that clearly extends far beyond either China or Korea.

Notes:[1] Gina Barnes, China, Korea and Japan: The Rise of Civilization in East Asia, London: Thames and Hudson, 1993, p.226. |