|

|||||||||

|

FEATURESLITIGATION SUROUNDING NAKHI ANCIENT MUSIC Detail depicting Thunder God and Lightning Goddess in mural titled Sermon Preached by Mahamayuri, dated 1583, Dabaoji Palace, Lijiang, Yunnan

Detail depicting Thunder God and Lightning Goddess in mural titled Sermon Preached by Mahamayuri, dated 1583, Dabaoji Palace, Lijiang, Yunnan

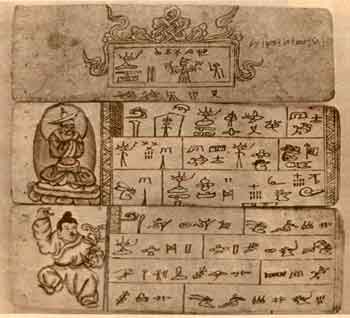

The idyllic setting inhabited by the Nakhi people has proved irresistible to Western adventurers ever since the eminent American explorer, botanist, anthropologist and photographer Dr Joseph Rock and the Russian-born Taoist doctor Dr Peter Goullart, a field officer for the Chinese Industrial Co-operatives or Gung-Ho movement, were drawn to Lijiang in Yunnan in the 1940s. Rock's two-volume study The Ancient NaKhi Kingdom of Southwest China(Cambridge, Mass.: 1948) is a monument to de-institutionalised anthropology, while Goullart's The Forgotten Kingdomis a coy travel account testifying to the possibilities extended by living in remote locations. Like Luang Prabang and Kathmandu several decades previously, Lijiang today (see illustration) is a safe haven for the jaded traveller in a world rapidly shrinking as a result of globalization. The Nakhi people, alternatively named in English the Naxi, Naqxi, Nashi, Moxiayi and Mosha, inhabit the foothills of the Himalayas in Sichuan and Yunnan provinces and have affinities with the Tibetan, Qiang and Mosuo (Moso) ethnic groups. They are best defined as speakers of the Nakhi language and today number approximately 300,000. The Nakhi hieroglyphic script in which the spiritual texts of the culture are relayed is aesthetically arresting, like the Women's Language (Nüshu) of Hunan, and its appeal and idiosyncratic quality similarly thwart scholars attracted to and challenged by its interpretation.(see illustration) The religious culture of the Nakhi scholar-shamans or dtomba (Chinese: Dongba) is described by scholars as an amalgam of Tibetan Bön and Tibetan Buddhism (see illustration), as well as elements of local shamanism, Taoism and Confucianism. Nakhi culture is a syncretic blend of Tibetan, Han Chinese and local indigenous elements, and the Nakhi have been absorbing elements of Han Chinese culture at a steady rate over the past several centuries. The Chinese language has, however, been effectively displacing Nakhi for the past half century. Lijiang has in fact long been a town where Han Chinese and Nakhi peoples have blended, and most inhabitants of Lijiang today are bilingual or speak only Chinese. Only a handful of scholars and some shamans can still understand the Nakhi hieroglyphic scriptures and other texts (see illustration), despite the proliferation of decorative uses of the script in Lijiang.  Garuda figure in Nakhi illustrated funeral scroll.

Garuda figure in Nakhi illustrated funeral scroll.

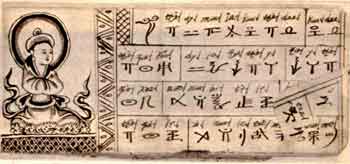

Nakhi culture is a living and changing culture, but its synthetic quality is not apparent from the hodgepodge designated as unique Nakhi culture and pedalled to tourists, appealing to a Shangri-la world of make-believe, something described in detail by the young Australian scholar Ben Hillman.[1] The novel The Lost Horizon (1933) by James Hilton, who also gave us Mr. Chips, and especially the script by Hilton (1937) on which Frank Capra's film was based, understandably had enormous appeal after the outbreak of the Second World War. However, it is strange that Shangri-La was subsequently imagined to be a real location intimately known to Hilton, although some knowledge of Yunnan may have been gleaned by Hilton from Joseph Rock's pieces for National Geographic. Various spurious etymologies of this invented Tibetan place name have been provided, and travellers have sought an authentic prototype for the fictional Shangri-la in such far-flung locations as Tibet, Nepal, Gilgit and Hunza, as well as various other Himalayan states – and Yunnan. In the 1990s, the government of Yunnan ended the search by officially renaming Zhongdian in Diqing Autonomous Tibetan Prefecture as Xiang'gelila. Lijiang lost out by a hair's- breadth but in 1997 Lijiang could feel compensated for losing out to a rival Yunnan town when it was inscribed by UNESCO as a world cultural heritage site. As Zhongdian is also inhabited by the Nakhi, Lijiang could also share in the reflected glory of Shangri-la. Nakhi ancient music, as promoted by Xuan Ke and performed for tourists in Lijiang by an ensemble of venerable old men with tortoise shell spectacles and pretty young girls with ruddy cheeks, is just one of the unique cultural properties of the Nakhi that can be sampled by visitors. Unfortunately, it was described by Wu Xueyuan, a musicologist from Yunnan, in the November 2003 issue of the journal Yishu pinglun (Art Criticism) as a cultural fraud. In an article, titled "Xuan Ke ji Naxi guyue: Naxi guyue daodi shi shenme dongxi?" (Xuan Ke and Nakhi Ancient Music: Just What Is This Thing Called Nakhi Ancient Music?), Wu questioned the characteristics used by Xuan Ke to define Nakhi Ancient Music:  Nakhi scripture celebrating the performance of the flower drum dance for a female deity.

Nakhi scripture celebrating the performance of the flower drum dance for a female deity.

[Nakhi Ancient Music] is in the first instance only a song and dance form, which it is inappropriate to designate as 'ancient music'. Secondly, the cultural origins of this song and dance form lie among the Han people, and it is inappropriate to classify it as belonging to the Nakhi people. Thirdly, among the Nakhi and extending all the way to the Yunnan borders there are many similar types of musical dance and it is inappropriate to single out this one example [as Nakhi Ancient Music]. Wu Xueyuan elaborated: To blend three quite different musical genres –remeica, Baisha "lyrical music" (xiyue) and Dongjing music – into a single entity and then give them the label "Nakhi Ancient Music" is a commercial exercise equivalent to advertising oneself as a halal butcher and purveying dog meat.  Detail from Nakhi Sutra of the Lighting of the Lamp.

Detail from Nakhi Sutra of the Lighting of the Lamp.

Xuan Ke sued the editor of the journal, Tian Qing, and the scholar Wu Xueyuan in the Lijiang People's Court for damaging his reputation by publishing and writing respectively an article questioning the authenticity of Nakhi ancient music and its credentials to qualify as a "living fossil of Chinese music" in the application made for its inclusion on the prestigious UNESCO list of intangible cultural heritage properties. The court in Lijiang awarded Xuan Ke, the Svengali of Nakhi Ancient Music, RMB 1.2 million yuan in damages to be paid by the journal's editor, as well as RMB100,000 to be paid by Wu Xueyuan. However, the court refused to accept as evidence the arguments in the article itself, ruling that these were scholarly matters for experts. This is similar to excluding DNA and other forensic evidence in a murder trial. In an interview with a reporter,[2] Xuan Ke, the promoter of Nakhi Ancient Music, defended himself against Wu Xueyuan's charges, although Wu points out that he is not concerned with Xuan Ke's creative and promotional activities, but with the fact that he was seeking a UNESCO listing for Nakhi Ancient Music as an intangible cultural heritage item. Xuan Ke vociferously argued: Nakhi Ancient Music is ancient music preserved by the Nakhi ethnic group, and its integrity and authenticity are undeniable.... Some scholars argue that Nakhi Ancient Music is a type of music that was introduced during the Hongwu reign period of the Ming dynasty [1368-98CE] to the Lijiang area from the Central Plains and, not being a pure heritage of the Nakhi nationality, it is not entitled to seek a listing by UNESCO as a part of world cultural heritage. Moreover, they charge that I wave the Nakhi flag to make money, but this is pure deceit based on ignorance. Our music comes from the Hongwu reign, giving it a 622 year history. Surely over this long span of time it has come to be synthesised and identified for its Nakhi musicality and style? Peking Opera was introduced to Beijing in the 55th year of the reign of the Qianlong Emperor [1736-95] by the Four Major Troupes from Anhui, giving it a history in the capital of only 212 years, yet Peking Opera has achieved recognition. I have been humiliated in print for insisting that Nakhi Ancient Music belongs to the Nakhi nationality. Moreover, that article was published in a journal run by an authoritative organisation which will surely have the most detrimental effect on Nakhi ancient music. The Lijiang People's Court only took into consideration the several sarcastic phrases from the article cited above ("this thing", "dog meat" etc.), and refused to admit any intellectual arguments in evidence, saying that these were technical matters for specialists. Therefore, the question remains unanswered: Does Nakhi Ancient Music fulfil the criteria for a UNESCO listing? Wu Xueyuan insists that Nakhi Ancient Music remains the commercial name for an evening's entertainment first used by Xuan Ke in 1995, and that the three distinct musical genres –remeica, Baisha "lyrical music" (xiyue) and Dongjing music – blended by Xuan Ke for performance as Nakhi Ancient Music are unrelated: Dongjing music was spread through more than 100 counties in Yunnan and was a genre of sacrificial and ritual music performed for the upper strata of the Han literati having no relationship to the original Nakhi lifestyle. Baisha xiyue was a form of ritual music performed in the administrative compound of the tusi [Aboriginal Administrators, i.e. local governors] that only permeated among the people in the Yongzheng period of the Qing dynasty [1723-35], when it was appropriated by Nakhi commoners for use as funeral music. Remeica is an ancient type of performance music of the Nakhi people, but it is mostly used to accompany singing and dancing during mourning activities in mountain areas inhabited by the Nakhi.  View showing water wheel beside the entrance to the ancient city of Lijiang.

View showing water wheel beside the entrance to the ancient city of Lijiang.

Wu Xueyuan points out that the UNESCO's intangible cultural heritage listings are for pure cultural forms. Nakhi Ancient Music, as named and performed by Xuan Ke's troupe after 1995, originally consisted of only Dongjing music. Only at the time of applying for UNESCO listing did Xuan Ke rush to include remeica and Baisha "lyrical music" (xiyue) in his "chop-suey" of Nakhi Ancient Music, according to Wu. In the short term, Xuan Ke may have succeeded in gaining economic redress, but his attempt to stifle genuine academic debate failed. On 15 January 2005, the "guilty" parties organised a colloquium at the Chinese Academy of the Arts at which the intellectual and legal issues related to Nakhi Ancient Music were enunciated, and the more general implications of the Lijiang court decision for objective debate on cultural heritage issues were spelled out. The colloquium was addressed by a veritable who's who of musical scholars, as well as legal experts and media figures.[3] At the colloquium, extensive excerpts from which can be read on line in Chinese,[4] the participants concurred with the view that not only was Nakhi Ancient Music a fraud that had nothing to do with the Nakhi people, but that the music itself was execrable. Zhao Shimin, a well-known music critic, quoted amusing excerpts from his article titled "Is Nakhi Ancient Music really the ancient music of the Nakhi?" published in Yinyue shenghuo (Musical life) in 1998: We went to enjoy Lijiang noodles, but were served up Lanzhou spaghetti. ... The compere introduced each item with a romantic explanation of what was to follow, but the force of the rhetoric could do nothing for the music. In other words, it was giant's talk for dwarf's music. ... When one of the items on the program was incorrectly introduced, [Xuan Ke] was not content to simply correct Zhao Zhongxiang [China Central Television/CCTV's most prominent concert host] but insisted on lecturing him on how to compere a musical evening: "When you announce that the program is over, there is no need to show how au fait you are with particular foreigners. When you're staging a show like this at the Concert Hall there's no need to make out that you're the only serious person in the place, and then sneer at popular music for not being serious". Because CCTV had not invited the Ancient Music troupe to participate in their Spring Festival Spectacular he attacked CCTV for having no discrimination: "If we're not invited next year, then you'll be hearing more of the same from us". There was no shred remaining of the purity and generosity we associate with frontier ethnic groups. ...After the concert, I asked Professor Wang Zhenya, editor-in-chief of Music Writing: "What did you think about that?" He replied: "Well, what's there to think about?!" Someone joined in: "But if there's nothing to think about, why have they been invited to perform in so many countries and at so many foreign universities? Could the aesthetic sensibilities of foreigners have dropped to such an all-time low?" Despite the light relief which Zhao Shimin lent to the colloquium, the basic issue being debated is of serious import: Does a scholar, or anyone for that matter, have the right to question another person's claims, spurious or not, on intellectual grounds? Given the plethora of spurious traditions being invoked in China for political and economic purposes at the present time, does anyone have the right to deflate any bogus cultural claims without being accused of defamation? Ms. Liu Suola, a musician and novelist from Beijing (famous in the 1980s for her early avant-garde short stories), spelled them out in a short, emotional speech: [When I read the materials related to this case] I get the feeling that Xuan Ke is representative of a lot of people in this day and age ... He likes to be photographed with officials, but if you attack him, he says that you are attacking the officials with him. He wants to use this ancient music to make a name for himself, comparing himself to [the late Peking Opera star] Mei Lanfang. But as soon as someone raises objections, he resorts to litigation, that being a path to fame, as it attracts the attention of the media and a large audience. But he has managed to make money through what he has cooked up, quite a lot of money in fact. For the moment the local government is on his side, and so he supports the local government and he works to their advantage. But the local government wants development, they want people who understand English and they want the attention of the West. Above all they want lots of foreign tourists to generate money. So it's not just a question of Xuan Ke making a name for himself overseas, they're also making a name for themselves. So you find yourself pitted against a strong camp, it's not just about Xuan Ke. Many academics are gathered here today who have many years of research behind them, and such enlightened scholars are national treasures. But when will the government truly take you seriously? This is an important question that warrants their attention. Only when the government takes scholarship seriously and regards it as something that represents the nation and this age, and regards this as something of value produced in this country and in these times, will the problems we face have any resolution. Otherwise we live in tragic times. . It is not clear whether Tian Qing and Wu Xueyuan have any further legal recourse, except through the High Court of Yunnan. On 11 March 2005 Xinhua News Agency carried a brief item, which may be the end of the story: Four musicologists attending the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference in Beijing argued that art criticism has the right to expose "spurious cultures". However, the CPPCC has little power and is not likely to create a precedent by upholding such a vague general notion as the freedom of academic enquiry and expression. However, it is almost certain that Nakhi Ancient Music will not get a UNESCO listing for many years to come, and the days of Xuan Ke's performances might be numbered. It is distinctly possible that Xuan Ke is himself a victim, and that he was enticed into the blind alley of Nakhi ancient music by reading a few particularly purple, and absurd, passages in Ch. XV (Music, Art and Leisure among the Nakhi) of Peter Goullart's The Forgotten Kingdom: The New Year celebrations provided the old gentlemen of Likiang with an opportunity to stage several concerts of sacred music in which they were adept. Madame Lee's husband was also a musician in his own right and heartily participated in these highbrow functions. The concerts were a unique institution and were so inspiring and interesting that I never failed to attend them. It was wonderful and extraordinary to hear the music which was played during the hey-dey [sic] of the glorious Han and Tang dynasties, and probably during the time of Confucius himself. This musical tradition was one of the most cherished among the Nakhi and was zealously transmitted from father to son. A well-to-do Nakhi in the city could only be accepted as a real gentleman if he knew this ancient music or was a fully fledged Chinese scholar. When I discovered this noble academic preoccupation of the Nakhi men, I felt a new respect for them. I forgave the Nakhi women for over-indulgence to their menfolk. They gave them leisure, and at least a part of it did not go to waste. Spoilt they were, these Nakhi men, and many smoked opium to excess, but passing years mellowed them and turned their hearts to the attainment of culture and of the understanding of beautiful things.... An image of an addled orchestra begins to emerge through the mists of opium smoke that obscure us from the 1940s, leaving us with the sense that the Nakhi might well have a tradition of telling a guest what he most wants to hear. Peter Goullart, the self-proclaimed Taoist, knows where this music is coming from: The present-day Chinese falsetto singing and the discordant and shallow music of Chinese theatres are no more representative of the ancient classical music of China than modern jazz is representative of classical Greek music. Some esoteric Taoist monasteries have preserved fragments of the classical music and they perform it in their ceremonies and dances, but the instruments and the score they use are far less genuine than those preserved by the Nakhi. Ultimately, the performance is everything, and Peter Goullart is transported by this music from a lost world forgotten by time: ... This gong show and golden shower charade raises important questions about musicology and musical traditions generally: What degree of innovation or invention is permissible in the preservation of a musical tradition? Is it possible to create or re-create a musical tradition that is not documented? How do "ancient" musical cultures achieve commercial sustainability? Is ethno-musicology simply obsolete? [BGD] NOTES:[1] Ben Hillman, "Paradise Under Construction: Minorities, Myths and Modernity in Northwest Yunnan", Asian Ethnicity, Volume 4, Number 2, June 2003. [2] China Radio International's interview drawn from Chengdu wanbao (Chengdu Evening News) can be read in Chinese at: http://gb.chinabroadcast.cn/3821/2004/10/27/501@341483.htm [3] The music scholars included: Tian Qing, researcher and PhD supervisor, editor-in-chief of Yishu pinglun; Tian Liantao, musical theorist and professor of the Central Academy of Music; Chen Mingdao, head of the department of music at the Chinese Music Academy; Li Xi'an, former head of the Chinese Music Academy; Feng Guangyu, former head of the Chinese Musicians Association; Dai Jiafang, head of the Institute of Music under the Central Academy of Music; He Shaojun, critic and editor-in-chief of Xiaoshuo xuankan (Selected Fiction); Zhang Zhentao, head of the Institute of Music of the Chinese Academy of the Arts; Guo Wenjing, professor of the Central Academy of Music; Wu Zuolai, deputy editor-in-chief of Wenyi lilun yu piping; Liu Suola, writer and musician; Jin Xiang, song writer and professor of the Chinese Music Academy; Yu Qingxin, deputy editor-in-chief of Renmin yinyue; Huang Dagang, editor of Yinyue yanjiu; Wan Li, lawyer from Yunnan; Wang Daren, lawyer from Yunnan; Huang Dongli, researcher at the International Legal Centre of CASS; Huang Qinnan, professor Zhongguo Zhengfa Daxue; Chen Zhiyin, deputy editor-in-chief of Yinyue zhoukan; Peng Li, chief editor of Beijing ribao; Xu Jiali, adjunct professor at the IPR Centre of CASS; Qiao Zhanxiang, lawyer; Wang Kun, singer and social activist; Fu Qin, art critic and professor of the Zhongguo Xiqu Xueyuan; etc. [4] See: http://arts.tom.com/1003/2005222-19793.html [5] The full original text can be read online at: http://www.pratyeka.org/books/forgotten_kingdom/ REFERENCES AND LINKS:CRI's interview drawn from Chengdu wanbao (Chengdu Evening News) can be read in Chinese at: http://gb.chinabroadcast.cn/3821/2004/10/27/501@341483.htm Peter Goullart, The Forgotten Kingdom, is available online: (http://www.pratyeka.org/books/forgotten_kingdom/). Harvard University is the holder of most of Joseph Rock's ethnological and botanical material. See: http://www.people.fas.harvard.edu/~chgis/data/chgis/downloads/v1/datasets/rock/ http://www.arboretum.harvard.edu/ Joseph Rock's images can also be viewed at: The Library of Congress holds a number of Nakhi documents and selections can be viewed at: |