|

||||||||

|

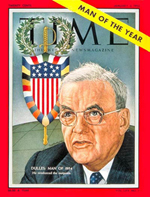

FEATURES1959: Preventing Peaceful EvolutionQiang ZhaiMao Zedong's policy response to John Foster Dulles's Peaceful Evolution strategy was originally articulated in Hangzhou in November 1959. As the scholar of Chinese international relations Qiang Zhai points out in his introduction to a translation of material from Bo Yibo's memoirs, it also had a profound impact on China's internal politics and the Sino-Soviet split of the 1960s.  John Foster Dulles (1888-1959) Since the initiation of the Reform era some three decades ago, the Party's policy on Peaceful Evolution has effectively been evacuated of its earlier pro-socialist ideological content. What remains is a theoretical justification sanctioned by both Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping for a nationalism (or 'Chinese particularism') wedded to authoritarian one-party politics. Deng and his colleagues were quick to blame the United States and other countries for politically manipulating the 1989 Protest Movement and attempting to use civil unrest in China to turn the country into a 'bourgeois vassaldom' of the West. This 'plot' aimed at encouraging China to peacefully evolve into a democracy dependent on international capital was supposedly the continuation of a struggle in which China's Communist Party had been engaged since the late 1950s. Ironically, Deng's internal Party opponents subsequently used the theory of Peaceful Evolution to oppose the next, bolder economic reforms that were initiated in 1992. We should note that the Party's anxiety over Peaceful Evolution still informs many of its political, social, cultural and media policies. This topic will be taken up again in the September 2009 issue of China Heritage Quarterly. The following material is printed with the kind permission both of the author and of the publisher. It originally appeared in the Bulletin of the Cold War International History Project (6/7—Winter 1995): 227-30, which was devoted to a discussion of the Cold War in Asia. The Cold War International History Project (www.cwihp.org) works under the aegis of The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington (see: WWICSW). While the original formatting has generally been retained, Chinese characters have been added where deemed necessary. Bo Yibo, one of the Communist Party's powerful 'Eight Immortals', went to 'meet Marx', as the saying has it, on 17 January 2007 at the age of 99. After his demise a series of comments on the Party and its predicament attributed to him as his 'last words', were circulated on the internet. See 'Final advice from Bo Yibo?', at: Bo's Last Words—The Editor. Mao Zedong and Dulles's 'Peaceful Evolution' Strategy: Revelations from Bo Yibo's MemoirsIntroduction, translation and annotation by Qiang ZhaiBorn in 1905, Bo Yibo joined the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1925. During the Anti-Japanese War, he was a leading member of the CCP-led resistance force in Shanxi Province. In 1945, he was elected a member of the CCP Central Committee at the Party's Seventh Congress. During the Chinese Civil War in 1946-1949, he was First Secretary of the CCP North China Bureau and Vice Chairman of the CCP-led North China People's Government. After the establishment of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in October 1949, he became Finance Minister…. Between 1991 and 1993, Bo published two volumes of his memoirs, Ruogan zhongda juece yu shijian de huigu 若干中大决策与事件的回顾 [Recollections of Certain Major Decisions and Events], Beijing: Zhonggong zhongyang dangxiao chubanshe, 1991, 1993. The first volume covers the period 1949-1956 and the second volume 1957-1966. In the preface and postscript of his volumes, Bo notes that in preparing his memoirs he has consulted documents in the CCP Central Archives and received the cooperation of Party history researchers. Bo's reminiscences represent the most important memoirs of a high-ranking CCP leader for the 1949-1966 period. As a still active senior leader, Bo is not a disinterested writer. His arguments and conclusions are completely in line with the 1981 Resolution on Party History.[1] Memoirs in China usually have a didactic purpose that encourages the creation of edifying stereotypes. Bo's memoirs conform to a tradition in the writing of memoirs in the PRC: didacticism. Arranged topically, Bo's memoirs are dry and wooden. There is little description of the character and personalities of his colleagues. In this respect, Bo's volumes follow another memoirs-writing tradition in the PRC, which tends to emphasize the role of groups and societal forces at the expense of individuals. Despite these drawbacks, Bo's memoirs contain many valuable new facts, anecdotes, and insights. Especially notable are Bo's references to Mao's statements unavailable elsewhere. Since Bo played a major role in Chinese economic decision-making during the period, his memoirs are especially strong on this topic. He sheds new light on such domestic events as the Three-Anti and Five-Anti Campaigns, the Gao Gang-Rao Shushi Affair, the Anti-Rightist Campaign, the Criticism of Opposition to Rush Advance, the Great Leap Forward, the Lushan Conference of 1959, economic rectification in 1961-1962, and the Socialist Education Campaign. Although international relations in general does not receive much attention, the volumes do include illuminating chapters on some key foreign policy decisions.[2] The translation below is taken from Chapter 39 of the second volume (pp.1138-1146). This section is very revealing about Mao's perception of and reaction to John Foster Dulles's policy toward China in 1958-1959. The CCP leader took seriously statements by the U.S. Secretary of State about encouraging a peaceful change of the Communist system. In November 1959, according to Bo, Lin Ke, Mao's secretary, prepared for Mao translations of three speeches by Dulles concerning the promotion of peaceful evolution within the Communist world. After reading the documents, Mao commented on them before having them circulated among a small group of Party leaders for discussion. Thus Bo's memoirs not only provide fresh texts of what Mao said, but also an important window into what he read. As a result, the interactive nature of Mao's activities—with his top colleagues and his secretary—is open to examination. A sense of the policy-making process, as well as Mao's opinions, emerges from Bo's memoirs. The years 1958-1959 were a crucial period in Mao's psychological evolution. He began to show increasing concern with the problem of succession and worried about his impending death. He feared that the political system that he had spent his life creating would betray his beliefs and values and slip out of his control. His apprehension about the future development of China was closely related to his analysis of the degeneration of the Soviet system. Mao believed that Dulles's idea of inducing peaceful evolution within the socialist world was already taking effect in the Soviet Union, given Khrushchev's fascination with peaceful co-existence with the capitalist West. Mao wanted to prevent that from happening in China. Here lie the roots of China's subsequent exchange of polemics with the Soviet Union and Mao's decision to restructure the Chinese state and society in order to prevent a revisionist 'change of color' of China, culminating in the launching of the Cultural Revolution in 1966. Mao's frantic response to Dulles's speeches constitutes a clear case of how international events contributed to China's domestic developments. It also demonstrates the effects of Dulles's strategy of driving a wedge between China and the Soviet Union. To Prevent 'Peaceful Evolution' and Train Successors to the Revolutionary CauseBo Yibo 薄一波 Bo Yibo (1908-2007) According to the general law of socialist revolution, only through the leadership of a proletarian political party directed by Marxism, reliance on the working class and other laboring masses, and waging of an armed struggle in this or that form can a revolution obtain state power. International hostile forces to the newly born people's government would always attempt to strangle it in the cradle through armed aggression, intervention, and economic blockade. After the victory of the October Revolution, the Soviet Union experienced an armed intervention by fourteen countries. In the wake of World War II, imperialism launched a protracted 'Cold War' and economic containment of socialist countries. Immediately after the triumph of the revolution in China and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, U.S. imperialists invaded Korea, blockaded the Taiwan Strait, and implemented an all-out embargo against China. All of this shows that it will take a sharp struggle with external hostile forces through an armed conflict or other forms of contest before a newly born socialist country can consolidate its power. History suggests that although the armed aggression, intervention, and economic blockade launched by Western imperialists against socialist countries can create enormous problems for socialist countries, they have great difficulty in realizing their goal of overthrowing socialist states. Therefore, imperialist countries are inclined to adopt a 'soft' method in addition to employing 'hard' policies. In January 1953, U.S. Secretary of States Dulles emphasized the strategy of 'peaceful evolution'. He pointed out that 'the enslaved people' of socialist countries should be 'liberated', and become 'free people', and that 'liberation can be achieved through means other than war', and 'the means ought to be and can be peaceful'. He displayed satisfaction with the 'liberalization-demanding forces' which had emerged in some socialist countries and placed his hope on the third and fourth generations within socialist countries, contending that if the leader of a socialist regime 'continues wanting to have children and these children will produce their children, then the leader's offspring will obtain freedom.' He also claimed that 'Chinese communism is in fatal danger', and 'represents a fading phenomena', and that the obligation of the United States and its allies was 'to make every effort to facilitate the disappearance of that phenomena', and 'to bring about freedom in all of China by all peaceful means.'[3] Chairman Mao paid full attention to these statements by Dulles and watched carefully the changes in strategies and tactics used by imperialists against socialist countries. That was the time when the War to Aid Korea and Resist America had just achieved victory, when the United States was continuing its blockade of the Taiwan Straits and its embargo, and when our domestic situation was stable, 'the First Five-Year Plan' was fully under way, economic construction was developing rapidly, and everywhere was the picture of prosperity and vitality. At that moment, Chairman Mao did not immediately bring up the issue of preventing a 'peaceful evolution'. The reason for his later raising the question has to do with developments in international and domestic situations. In 1956, at the 20th Congress of the Soviet Communist Party, Khrushchev attacked Stalin, causing an anti-Communist and anti-Socialist wave in the world and triggering incidents in Poland and Hungary. In 1957, a tiny minority of bourgeois Rightists seized the opportunity of Party reform to attack the Party. In 1958, Khrushchev proposed to create a long-wave radio station and a joint fleet with China in order to control China militarily; he also openly opposed our Party's 'Three Red Flags'[4] and objected to our just action of 'shelling Jinmen'.[5] (Chairman Mao once said that whether we bombarded Jinmen or suspended our bombardment, our main purpose was to support the Taiwan people and the Taiwan regime to keep Taiwan [from being] invaded and annexed by foreign countries.—Bo's note). The above events alerted Chairman Mao. In the meantime, the United States actively practiced its strategy of promoting a 'peaceful evolution' of socialist countries. In 1957, the Eisenhower administration introduced the 'strategy of peaceful conquest', aiming to facilitate 'changes inside the Soviet world', through a 'peaceful evolution'. On October 24, 1958, in an interview with a BBC correspondent, Dulles asserted that communism 'will gradually give way to a system that pays more attention to the welfare of the state and people', and that at the moment, 'Russian and Chinese Communists are not working for the welfare of their people', and 'this kind of communism will change'. Considering the situation in both the Soviet Union and at home, Chairman Mao took very seriously Dulles's remarks. In a speech to the directors of the cooperation regions[6] on November 30, 1958, Chairman Mao noted that Dulles was a man of schemes and that he controlled the helm in the United States. Dulles was very thoughtful. One had to read his speeches word by word with the help of an English dictionary. Dulles was really taking the helm. Provincial Party Committees should assign special cadres to read Cankao ziliao 参考资料.[7] Chairman Mao has always insisted that Party leaders at all levels, especially high-ranking cadres, should closely follow international events and the development of social contradictions on the world scene in order to be well informed and prepared for sudden incidents. It is very necessary for Mao to make that demand. Chairman Mao read Cankao ziliao every day. For us leading cadres, we should consider not only the whole picture of domestic politics but also the whole situation of international politics. Thus we can keep clear-headed, deal with any challenges confidently, and 'sit tight in the fishing boat despite the rising winds and waves.' This is a very important political lesson and a leadership style. In 1959, Sino-Soviet relations were even more strained and Sino-Soviet differences even greater. In January, the Soviet Union officially notified China that it would scrap unilaterally the agreement to help China build nuclear industry and produce nuclear bombs. In September when the Sino-Indian Border Incident occurred, the Soviet Union announced neutrality, but in actuality it supported India. It openly criticized China after the incident. At the Soviet-American Camp David Talks during the same month, Khrushchev sought to improve relations with the United States on the one hand and vehemently attacked China's domestic and foreign policies on the other.[8] All these events convinced Chairman Mao that the Soviet leadership had degenerated and that Khrushchev had betrayed Marxism and the proletarian revolutionary cause and had turned revisionist. At the Lushan Conference held during July-August that year, when Peng Dehuai[9] criticized the 'Three Red Flags,' Chairman Mao erroneously believed that this reflected the combined attack on the Party by internal and external enemies. Facing such a complex situation, Chairman Mao felt deeply the danger of a 'peaceful evolution.' Accordingly, he unequivocally raised the issue at the end of that year. In November 1959, Chairman Mao convened a small-scale meeting in Hangzhou attended by Premier Zhou [Enlai], Peng Zhen,[10] Wang Jiaxiang,[11] Hu Qiaomu,[12] among others, to discuss and examine the international situation at the time. Before the opening of the meeting, Chairman Mao asked his secretary, Lin Ke 林克, to find Dulles's speeches concerning 'peaceful evolution' for him to read. Comrade Lin Ke selected three such speeches: Dulles's address titled 'Policy for the Far East' delivered before the California Chamber of Commerce on December 4, 1958, Dulles's testimony made before the House Foreign Affairs Committee on January 28, 1959, and Dulles's speech titled 'The Role of Law in Peace' made before the New York State Bar Association on January 31, 1959. Chairman Mao had read these three speeches before. After rereading them, he told Comrade Lin Ke of his opinions about them and asked him to write commentaries based on his views and insert them at the beginning of each of Dulles's statements. After Comrade Lin Ke had completed the commentaries, Mao instructed him to distribute Dulles's speeches, along with the commentaries, to the members attending the meeting. The three speeches by Dulles all contained the theme of promoting a 'peaceful evolution' inside socialist countries. The three commentaries based on Chairman Mao's talks highlighted the key points in Dulles's remarks and warned of the danger of the American 'peaceful evolution' strategy. The first commentary pointed out: 'The United States not only has no intention to give up its policy of force, but also wants, as an addition to its policy of force, to pursue a 'peaceful conquest strategy' of infiltration and subversion in order to avoid the prospect of its 'being surrounded'. The U.S. desires to achieve the ambition of preserving itself (capitalism) and gradually defeating the enemy (socialism).' After noting the main theme of Dulles's testimony, the second commentary contended: Dulles's words 'demonstrate that U.S. imperialists are attempting to restore capitalism in the Soviet Union by the method of corrupting it so as to realize their aggressive goal, which they have failed to achieve through war.' The third commentary first took note of Dulles's insistence on 'the substitution of justice and law for force' and his contention that the abandonment of force did not mean the 'maintenance of the status quo', but meant a peaceful 'change'. Then it went on to argue that 'Dulles's words showed that because of the growing strength of the socialist force throughout the world and because of the increasing isolation and difficulties of the international imperialist force, the United States does not dare to start a world war at the moment. Therefore, the United States has adopted a more deceptive tactic to pursue its aggression and expansion. While advocating peace, the United States is at the same time speeding up the implementation of its plots of infiltration, corruption, and subversion in order to re- verse the decline of imperialism and to fulfill its objective of aggression.' At the meeting on November 12, Chairman Mao further analyzed and elaborated on Dulles's speeches and the commentaries. He said: Comrade Lin Ke has prepared for me three documents—three speeches by Dulles during 1958-1959. All three documents have to do with Dulles's talks about encouraging a 'peaceful evolution' inside socialist countries. For example, at his testimony before the House Foreign Affairs Committee on January 28 Dulles remarked that basically the U.S. hoped to encourage changes within the Soviet world. By the Soviet world, Dulles did not mean just the Soviet Union. He was referring to the whole socialist camp. He was hoping to see changes in our camp so that the Soviet world would no longer be a threat to freedom on the globe and would mind its own business instead of thinking about realizing the goal and ambition of communizing the world.... In commenting on Dulles's statement of January 31, 1959, Chairman Mao asserted: Dulles said that justice and law should replace violence and that war should be abandoned, and law and justice should be emphasized. Dulles also argued that the abandonment of force under the circumstances did not mean the 'maintenance of the status quo', but meant a peaceful 'change'. (laughter) Change whom peacefully? Dulles wants to change countries like ours. He wants to subvert and change us to follow his ideas.... Therefore, the United States is attempting to carry out its aggression and expansion with a much more deceptive tactic.... In other words, it wants to keep its order and change our system. It wants to corrupt us by a peaceful evolution. Chairman Mao believed that Khrushchev's speeches reflected the 'peaceful evolution' advocated by Dulles and that our principle should be: Under the existing complex international conditions, our policy is to resist the pressures head-on—pressures from two directions, Khrushchev and Eisenhower. We will resist for five to ten years. Toward the United States, we should do our best to expose it with facts and we should do so persuasively. We will not criticize Khrushchev, nor will we attack him through implication. We will only expose the American deception and lay bare the nature of the so-called 'peace' by the United States. This is the first time that Chairman Mao clearly raised and insightfully elaborated on the issue of preventing a 'peaceful evolution'. From that time on, he would pay more and more attention to the matter. In a series of meetings that followed, he would repeatedly alert the whole party on the issue and gradually unfold the struggle against the so-called revisionism both at home and abroad. From 1960 forward, differences between the Chinese and Soviet Parties increased. On April 22, an editorial titled 'Long Live Leninism' published by the journal Hongqi 红旗[13] denounced Comrade Tito of Yugoslavia by name and criticized Khrushchev of the Soviet Union without mentioning his name. On internal occasions, we unequivocally pointed out that the Soviet Union had become revisionist and that we should learn the Soviet lesson. We also felt that 'revisionists' already existed in China and that Peng Dehuai and some other comrades were examples. We warned against the emergence of revisionism in order to prevent a 'peaceful evolution'. In his meeting with Jespersen,[14] Chairman of the Danish Communist Party, on May 28, 1960, Chairman Mao said: 'There are also revisionists in our country. Led by Peng Dehuai, a Politburo member, they launched an attack on the Party last summer. We condemned and defeated him. Seven full and alternate members of our Central Committee followed Peng. Including Peng, there are eight revisionists. The total number of full and alternate members in our Central Committee is 192. Eight people are merely a minority.' At the 'Seven Thousand Cadres Conference'[15] held in January 1962, Comrade [Liu] Shaoqi delivered a 'written report' on behalf of the Party Central Committee. He made a special reference to the question of opposing contemporary revisionism. In his remarks concerning the issue of practicing democratic centralism, Chairman Mao stated: 'Without a highly developed democracy, there cannot be a high level of centralism. Without a high level of centralism, we cannot establish a socialist economy. What will happen then to our country if we cannot create a socialist economy? China will become a revisionist country, a bourgeois country in fact. The proletarian dictatorship will become not only a bourgeois dictatorship but also a reactionary and fascist dictatorship. This is an issue that deserves full attention. I hope our comrades will consider it carefully.' (Selected Readings of Chairman Mao's Works, vol.II, pp.822-823.) Here Chairman Mao officially sounded an alarm bell for the whole party. In his meeting with Kapo[16] and Balluku[17] of Albania on February 3, 1967, Mao contended: At the 'Seven Thousand Cadres Conference' in 1962, 'I made a speech. I said that revisionism wanted to overthrow us. If we paid no attention and conducted no struggle, China would become a fascist dictatorship in either a few or a dozen years at the earliest or in several decades at the latest. This address was not published openly. It was circulated internally. We wanted to watch subsequent developments to see whether any words in the speech required revision. But at that time we already detected the problem.' At the Beidaihe Meeting and the Tenth Plenum of the Eighth Central Committee during August and September, 1962, Chairman Mao reemphasized class struggle in order to prevent the emergence of revisionism. On August 9, he clearly pointed out the necessity of educating cadres and training them in rotation. Otherwise, he feared that he had devoted his whole life to revolution, only to produce capitalism and revisionism. On September 24, he again urged the party to heighten vigilance to prevent the country from going 'the opposite direction.' The communiqué of the Tenth Plenum published on September 27 reiterated the gist of Chairman Mao's remarks and stressed that 'whether at present or in the future, our Party must always heighten its vigilance and correctly carry out the struggle on two fronts: against both revisionism and dogmatism.' From the end of 1962 to the spring of 1963, our Party published seven articles in succession, condemning such so-called 'contemporary revisionists' as Togliatti of Italy,[18] Thorez of France,[19] and the American Communist Party. On June 14, 1963, the CCP Central Committee issued 'A Proposal for a General Line of the International Communist Movement.' On July 14, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) published 'An Open Letter to Party Units at All Levels and to All Members of the CPSU', bringing the Sino-Soviet dispute to the open. From September last to July 1964, our Party used the name of the editorial boards of the Renmin ribao and Hongqi to issue nine articles, refuting the Soviet open letter and condemning 'Khrushchev Revisionism' by name. Thus the Sino-Soviet polemics reached a high point. In the meantime, the struggle to oppose 'revisionism' and to prevent a 'peaceful evolution' was accelerated at home.

Editor's Note:Qiang Zhai is a professor of history at Auburn University at Montgomery (Alabama). His books include The Dragon, the Lion, and the Eagle: Chinese-British-American Relations, 1949-1958, Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1994; and, China and the Vietnam Wars, 1950-1975, University of North Carolina Press, 2000. Notes:[1] The Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party since the Founding of the People's Republic of China was adopted by the Sixth Plenum of the Eleventh Central Committee in June 1981. While affirming the historical role of Mao Zedong, the resolution also blames him for the Cultural Revolution. After an analysis of all the crimes and errors in the Cultural Revolution the resolution describes it as, after all, 'the error of a proletarian revolutionary'. It concludes that although Mao has made 'gross mistakes' during the Cultural Revolution, 'if we judge his activities as a whole, his contribution to the Chinese revolution far outweighs his mistakes.' For the text of the resolution, see Resolution on CPC History (1949-1981), Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1981. [2] I have previously translated the chapter in the first volume concerning Mao's decision to make an alliance with the Soviet Union in 1949-1950. It was first published in Chinese Historians 5 (Spring 1992), 57-62, and later in Thomas G. Paterson and Dennis Merrill, eds., Major Problems in American Foreign Relations: Volume II: Since 1914, 4th ed., Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath, 1995, pp.332-34. [3] Bo does not mention precisely when and where Dulles made those remarks about Chinese communism. I have not been able to identify Dulles's speech to which Bo is referring. [4] The 'Three Red Flags' refer to the General Line of Socialism, the Great Leap Forward, and the People's Commune. [5] Jinmen (Quemoy). [6] These refer to the economic cooperation regions established during the Great Leap Forward. China was divided into seven such regions. [7] Cankao ziliao (Reference Material) is an internally circulated reading material, which provided Party leaders with translations and summaries of international news from foreign news agencies and press. [8] According to the U.S records of the Camp David talks, in his discussions with President Eisenhower, Khrushchev actually defended China's position on Taiwan. See memorandum of conversation between Eisenhower and Khrushchev, 26 and 27 September 1959, in Foreign Relations of the United States, 1958-1960, Vol. X, Part I: Eastern Europe Region; Soviet Union; Cyprus, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1993, pp.477-482. [9] Peng Dehuai, Defense Minister and a Politburo member. [10] Peng Zhen, Party Secretary of Beijing and a Politburo member. [11] Wang Jiaxiang, Director of the CCP International Liaison Department and a Secretary of the CCP Central Committee Secretariat. [12] Hu Qiaomu, Mao's political secretary and an Alternate Secretary of the CCP Central Committee Secretariat. [13] Hongqi (Red Flag) is the official journal of the CCP Central Committee. [14] Knud Jespersen, leader of the Danish Communist Party. [15] The conference was held between January and February, 1962 to review methods of Party leadership and examine problems caused by the Great Leap Forward. [16] Hysni Kapo, a leader of the Albanian Labor (Communist) Party.

[17] Bequir Balluku, Defense Minister and a Politburo member of the Albanian Communist Party. [18] Palmiro Togliatti, leader of the Italian Communist Party. [19] Maurice Thorez, leader of the French Communist Party. |