|

FEATURES

Tribute to Emeritus Professor Liu Ts'un-yan (1917-2009) | China Heritage Quarterly

<< Vale: Liu Ts'un-yan | << Vale: David Hawkes, Liu Ts'un-yan, Alistair Morrison

Tribute to Emeritus Professor Liu Ts'un-yan (1917-2009)

John Minford

John Minford is Professor of Chinese and Head of the China Centre at The Australian National University. He was a student of Liu Ts'un-yan's from 1977 to 1980.

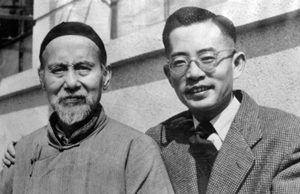

Professor Liu Ts’un-yan 柳存仁 with his father, Liu Tsung-ch'uan 柳宗權, in Hong Kong, 1953. Liu Tsung-ch’uan was one of the last to obtain the xiucai degree in the imperial exams. It is a great honour to have been asked by Selina, Professor Liu Ts'un-yan's daughter, to speak today in memory of her father, a man who was both my revered teacher, and my dear friend, over more than thirty years. I have accepted this honour humbly, on behalf of all of my colleagues, friends and fellow students, and on behalf of the university. I wish first to express our deepest condolence to her and to the other members of his family. I also wish to try to express our shared sense of gratitude to her father, for what he achieved in his lifetime and for what he has left for us. I do this in the knowledge that my words will inevitably fall far short of what would be worthy of him and his extraordinary achievement.

For those of us engaged in the study of China, Liu Ts'un-yan was quite simply one of the very last and most significant native exponents of his country's grand cultural tradition. He was a great master, in the real sense of that term. His passing truly marks the end of an era. The range and depth of his knowledge and understanding of Chinese culture, and his effortless ability to interpret and integrate all of its branches, were simply breathtaking.

Let me give one very small example. In 1952, Liu Ts'un-yan wrote a couple of short essays, zawen, reminiscences of Cheng Yanqiu, the famous Opera actor he had known when he was a teenager in Peking, in the late 1920s. These essays were originally written for the Hong Kong daily press, and were reprinted in 2001 by Shanghai Guji Press, under the title Waiguode yueliang, A Foreign Moon. In the second essay, Liu Ts'un-yan remarks in passing that the foundation of this great performing artist's success lay in his lifelong pursuit of neigong, of Taoist self-cultivation, including the practice of taiji quan, and of breathing techniques. This, done steadily and consistently over the years, was what maintained the high standard of his singing. A profound observation, lightly made. So much truth is contained in that effortless remark. Such insights as these were part and parcel of Professor Liu's everyday thinking, they informed his conversation.

More than once Liu Ts'un-yan explained to me that his lifelong involvement with Taoist philosophy and religion, a subject on which he became one of the world's unrivalled authorities, had arisen out directly of a personal experience during his childhood in Peking. He was a sickly child, and no physician, Chinese or Western, could be found to help him mend his health. He was finally taken to a Taoist monastery and there he was taken in hand by one of the monks. That was when he started learning some of the basic qigong practices that helped him in a very practical way throughout his long life. In the closing sentences of wide-ranging historical survey of Taoist religion, an essay published in the pages of Hong Kong's Ming Pao Monthly in 1980, he returns to this practical theme. Whatever else one might say about Taoism, he argues, it has done so much good for the men and women in our society.

It is hard to know where to begin. Liu Ts'un-yan was so many things at one and the same time. He was a Chinese scholar-gentleman at home in many branches of Chinese literature, classical and vernacular, and in many varieties of the Chinese language—Mandarin, Cantonese, Shanghai dialect. He once surprised me at a restaurant by lapsing into Shandong dialect, and went on to remind me that Shandong was his family's ancestral home. And yet for centuries his family had been Hanjun, Chinese Bannermen, honorary Manchus, inheritors of that proud tradition within a tradition.

He was the most meticulous scholar and teacher, able to rise to the demands of the most exacting textual scholarship, at home in the most arcane byways of the Confucian, Taoist and Buddhist classics. His scholarship was founded not on ideology or theory, but on close, indefatigable reading of central texts. He was a painstaking bibliographer, making copious notes wherever he went, at libraries all over the world. And yet behind this scholarly (and sometimes daunting) persona, was a man of great humanity and warmth, a playful man of letters, a witty essayist (again in both classical and colloquial Chinese), a fluent novelist and playwright.

Liu could be a devastating critic, wherever he discerned incompetence and pretentious, phony scholarship. I can recall seminars at which he decided that enough was enough, and proceeded to offer the speaker a few 'minor emendations'. And yet he was a prodigiously kind and generous mentor if he sensed the presence of a receptive mind.

Liu Ts'un-yan was both deeply conservative and irrepressibly mischievous. This was what made visiting him a constant delight, the prospect of being both instructed and entertained! Let me give a small example of his sense of humour and mischief, undiminished by old age. A couple of months before he died, he hosted a most convivial dinner for a visiting scholar from Chicago, Professor Anthony Yu, Yu Guofan, translator and interpreter of the great novel Journey to the West, or Monkey—Xiyou ji. This novel, and its problems of authorship, is one of the many subjects on which Professor Liu was himself a world-renowned authority and had published extensively. He was in great spirits that evening, and on the way to collect Professor Anthony Yu and his wife, he quipped from the passenger seat of our car: 'Wouldn't it have been fun on this occasion to treat our guests to the famous Cantonese delicacy, Monkey's Brains!'

It was Australia's extraordinary good fortune that in the early 1960s Liu Ts'un-yan chose to leave Hong Kong, where he had lived and worked since the end of the war, travel across the seas and join the ANU. He made Canberra his home for the last half of his life. He so nearly went instead to London University, where Walter Simon had offered him a short-term appointment. But he came here, and Britain's loss was Australia's gain. Over the subsequent decades did more than anyone to put the ANU on the world map of Chinese Studies. This has been officially recognised and honoured in various ways. But it is right today, in this hall, on this campus of which he was so fond, that we should pause to pay a special tribute to this dimension of his achievement, his work as an educator.

His deeply humanistic vision of Chinese Studies, as it should be in a fine university such as the ANU, was spelled out most eloquently in his own inaugural lecture, delivered on 5 October 1966: I quote:

As a product of Western civilisation the modern university had its origin in medieval European ecclesiastic education. Its objective was to produce an all-round man rather than to give technical and professional training... In the Humanities we still respect this great tradition. This is precisely what is meant by the Chinese classical saying: 'The accomplished scholar is not an utensil' junzi buqi 君子不噐 (Analects of Confucius, Book II, Chapter 12). That is to say, a scholar of moral integrity does not regard himself merely as an instrument.

What students of Chinese are learning appears to be an instrument. But it is an instrument only in the sense that it is a medium through which advanced studies in much broader fields may be made. A mere knowledge of the language does not in fact constitute the real understanding of that language. In order to understand the feelings expressed in the Chinese language one must be acquainted with at least some of the many rich works of literature which have been written in Chinese... We are concerned not only with a language and a literature but, through the learning of that language and literature, with something more lasting, a deeper, and hence more intimate and even sympathetic, understanding of the people whose language and literature we are studying.—from Liu Ts'un-yan, 'Chinese Scholarship in Australia', an inaugural lecture delivered at Canberra on 5 October 1966, pp.3-4.

I know how happy and proud Professor Liu was during the past three years to see for himself that this humanistic legacy of his was being taken seriously once more, that traditional Chinese studies were being revived, and that the ANU was once more taking the lead and standing up for these enduring values in Chinese Studies. He still wanted to be engaged. A few months ago he attended a seminar in our faculty on the subject of the 'New Sinology', at which this 'return to roots' in Chinese studies at the ANU was described quite plainly and forcefully. Liu Ts'un-yan read the paper carefully, and remarked to me quietly afterwards how much he agreed with what we were doing, adding with a smile: 'Of course there's actually nothing new about it!' For him this was so true, because all his life he had, in his own writings, in his own teaching, in his own person, embodied the very things we were striving to put back at the centre of our curriculum: a sense of cultural continuity and actuality, of the past in the present, and of the present in the past; a sense of the interconnectedness of literature, history and philosophy, of the lively links between scholarship and life. Professor Liu was right. It is not so much New Sinology we are after, it is just good Sinology. During his own lifetime, Liu Ts'un-yan and his colleagues made this university a place where good Sinology happened. Many of us here today studied here in that time, and owe our formation to his careful instruction. It is for that reason that we will miss Professor Liu all the more.

Liu Ts'un-yan was bearer of a great tradition. As a student at Peking University from 1935, he studied under Qian Mu, Hu Shi, Sun Kaidi, Chen Yinke, Guo Shaoyu, and many others. As his own stature grew, he himself went on to become one of the key members of a worldwide circle of great scholars and critics, many of whom were his personal friends, and most of whom have by now sadly passed away: Paul Demieville, Arthur Waley, A C. Scott, Stephen Soong, Yang Tsung-han, Wu Shichang, Qian Zhongshu (he had known his father Qian Jibo while still at high school), David Hawkes, C.T. Hsia, Jao Tsung Yi,to mention only a few. He considered these relationships in a very special light. Of Hawkes, he wrote in 2002: 'This relationship of ours is rather a complex one. In fact, there seems to me almost to be some inexplicable element of karma involved, some form of predestination at work.' He saw such friendships as pools of light in the darkening times around him. He wrote, again in 2002: 'In these troubled times, when all the talk is of the turmoil and chaos of war, to have had a friendship like this, that has lasted half a century, is indeed something to be treasured.' The very idea of friendship, friendship of kindred spirits, of like-minded scholars and men of letters working together across the boundaries of geography and language, indeed of time itself (for his wonderful library held many good friends), the notion that all of this was a force for good lay at the heart of everything he did. In a short casual essay republished in China in 2001, he ascribed to the perennial philosophy of China a crucial role as mediator in a chaotic, and materialistic age. But when he said this, he was referring to hard-won truths, to genuine wisdom, not to the facile pressing into service of Taoism for political ends, of which he took a very dim view.

More and more with the passing of the years he spoke with utter simplicity of the need to distinguish between what was genuine, zhen, and what was false, jia. In the end, he insisted many times, this was all that really mattered. Such distinctions came easily, were indeed self-evident, to a man who had practised his own philosophy unpretentiously but consistently over the years, and who seemed in his last years to have become almost luminously transparent. What he said to me a long time ago about the Hawaii-based philosopher Chang Chungyuan, was eminently true of Liu Ts'un-yan himself: the Tao was in his face.

If I may be permitted to end on a personal note, my most enduring memory of Professor Liu will be of the three and a half years, from April 1977 to August 1980, when I was his PhD student. Every Wednesday afternoon, he would sit down with me, share an apple, and generously guide me down ever more fascinating paths in the literature that he knew so well. For several months we read together a selection of ci-poems, exploring the sensibility of that strange lyric world. He recited the poems, and often as he did so, his voice would catch with emotion. To use the words of that other great scholar and man of letters, Wang Guowei, whom Professor Liu resembled in so many ways, the world of the lyric was for him a complete inner realm, a realm in which he lived and breathed: he knew its moods, its language, its turns, its hidden emotions and understatements. It accorded closely with a side of his own personality, slightly, lightly melancholic, subtly lyrical, concerned with the evanescence of human life, with seeing through the Red Dust, and yet paradoxically in love with the very beauty of that dust. He shared this sensibility so generously, teaching me that the same mood pervades the great novel Hongloumeng, The Story of the Stone, another work on which he was an acknowledged authority.

Liu Ts'un-yan's passing leaves us bereft of an irreplaceable voice, a voice speaking quietly but eloquently for China in all of its power and glory, in all of its triumphs and failings, at a time when the importance of such a true understanding of China is greater than ever. He leaves us acutely aware of our own inadequacy, acutely aware of how for so long we have been as dwarfs standing on his shoulders, seeing with his eyes, hearing with his ears, relying on his endless hard work, and his faultless instinct for the truth. He leaves us painfully conscious of the void none of us is qualified to fill. Without that infallible guide, how can we proceed? We can only try to take heart from his example, from his rich wealth of published scholarship, and do our utmost to keep his legacy alive.

|