<< Vale: David Hawkes, Liu Ts'un-yan, Alistair Morrison

In Memoriam: Emeritus Professor Liu Ts'un-yan, AO, (1917-2009)

Pierre Ryckmans

I had the privilege to know Professor Liu for nearly forty years: I admired the scholar and I loved the friend. It would be impossible to convey in a few words all what this has meant for me. In my younger days, the temptation would have been simply to abandon myself to my recollections—but now, in old age, I do not dare to do so, as I would run the risk either, of losing the thread of my talk, or forgetting when to stop. To avoid this double danger, I just wrote down a few personal remarks, as a contribution to this collective homage we are paying here to his memory.

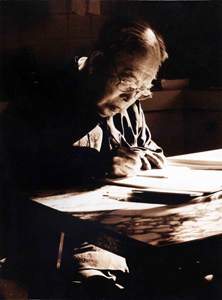

Professor Liu in his study, June 2004. Photo: Ingrid Fung, his grand-daughter.

Regarding Professor Liu, the scholar: one point should be emphasized, as it might sometimes have escaped the general perception. Chinese studies were formerly called "sinology" —a word that lately fell into relative disuse, as many students in our field now prefer to define themselves by their respective specialisations—and they would call themselves (let us say) historians, or linguists, literary historians, sociologists, political scientists—whatever. They rightly feel that, if they were to call themselves "sinologists", this would imply an almost absurd ambition – as if they could be conversant with the totality of four thousand years of Chinese culture. In Western terms this would be as if scholars of classical Greece, or of English literature, or of French history, would present themselves as "Europeanologists". It seems indeed as if a learning which would encompass all the main aspects of Chinese civilisation through the ages should be, by definition, beyond the grasp of any individual mind, as it would entail an intellectual storing capacity that is simply superhuman. And yet—this is precisely what was accomplished in China by a small elite of highly educated scholars. Professor Liu was one of the last representatives of what was truly a generation of intellectual giants. And it was truly the good fortune of Australia that he chose to spend here the second half of his long and fruitful career.

In front of Professor Liu, even senior scholars felt like humble students—we all acknowledged him as our master, and constantly sought his guidance. At all times he was most approachable and kind: he shared his learning with generosity, and always imparted his light with a sought of modest diffidence. When consulted on any question, if he felt only 98% sure of the correct answer, his reply would always be qualified with many "perhaps" and "maybe"; —and if he was 100% sure, he would still say "perhaps" and "maybe", simply to smoothen courteously the bruising impact of certainty. Intellectual arrogance was totally foreign to him, for arrogance is often the self-defence of an ignorant mind. Great learning, on the contrary, always generates tolerance, and prudence, and modesty—qualities that are encountered only at the highest level of intellectual eminence. "Que sais-je?" (What do I know?) was the motto which Michel de Montaigne, one of the most learned men of Europe in his time, had carved on the main beam of his study room. In his attitude, Professor Liu always seemed to keep a similar question before the eye of his mind.

Professor Liu spent all of his life in the company of books, ceaselessly reading, studying and writing. And yet he was the very opposite of a dessicated bookworm. Though his own scholarly works form a monumental collection, covering fields as diverse a philosophy, literature and history, it is worth noting that, in his early years, he also wrote theatrical plays—even movie scripts—and one big novel. The fact is: he looked at the outside world with inexhaustible curiosity, he enjoyed human contacts, was interested in other people (though he never indulged in any form of gossip), he loved travel (and with his open mind ever ready for new discoveries, he was a delightful travelling companion). At the university, as head of the Chinese department, he still took a full share of our common teaching load; and as Dean of the Asian Studies Faculty, even though administrative obligations must have been distasteful to him (he had so many better things to do!) he always discharged his responsibilities with scrupulous zeal—and with great success, for, under his administration, harmony and success always prevailed.

He obviously cultivated a rich inner life. Though we naturally had no direct access to this, we could measure its quality by its fruits: the serene equanimity of his mood, the constant kindness he extended to all. His spiritual philosophy was (I think) the product of a natural convergence: he fulfilled his social and professional duties according to Confucian ethics. He controlled his motions and maintained inner calm through the practice of meditation and Taoist discipline. All forms of religious experience interested him—and not only from a scholarly point of view. (I know for instance that he had read the Christian Gospels with attention and respect.) The spirit of Buddhist compassion constantly inspired his actions. He achieved a quality of integrity, detachment and serenity that should remain an example for all of us.

As I said at the beginning, we were most fortunate in having him among us for so long, as out teacher and our guide, But I must also add that, in one respect at least, he too was very fortunate; for all his adult life and well into his old age, he received the loving support of his wife—Mrs. Liu was indeed a remarkable personality: strong and devoted, wise, discrete and generous. Then, after her death, he was surrounded by the love of his children and grand-children. In particular his daughter Selena and son-in-law, Dr. Joseph Fung, looked after him in such a way, that he was able to maintain his old style of life unchanged: he could remain in his old house, with all his books at hand, and continued to read, to study, and to write as he had always enjoyed to do, nearly till his very last days. The principles and precepts of filial piety fill many Chinese treatises; but what Selena and Joseph showed us, simply and silently, is filial piety in action—and this is beautiful.

Canberra, 24 August 2009