|

||||||||||

|

FEATURESFragile ProsperityGloria Davies* Monash University

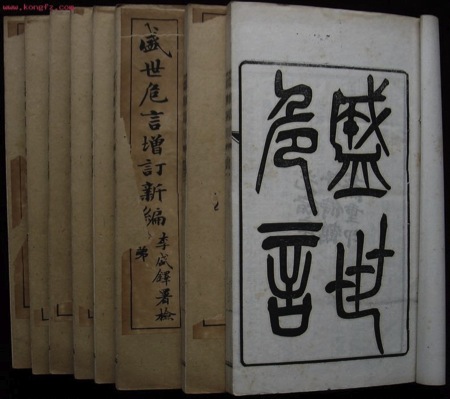

This essay is based on the author's presentation at the 'Shengshi Zhongguo 盛世中国 Flourishing China, myths and realities' roundtable at The Association for Asian Studies annual conference, 31 March 2011. Since the article substantively engages with pre-contemporary China, traditional characters have been used in the body of the text.—The Editor In 1893, when Zheng Guanying 鄭觀應 (1842-1922) published Words of Warning to a Prosperous Age (Shengshi weiyan 盛世危言, hereafter Words of Warning), he was a successful Shanghai-based comprador who also held the official title of Circuit Intendant (daotai 道臺). Like many wealthy merchants of his day, Zheng's aspirations to officialdom were realized through the purchase of official titles. He bought his earlier titles but later ones (including that of daotai) were awarded in recognition of his contributions to disaster relief work and to various public causes. He was first promoted to expectant daotai in 1879 and later rose to higher positions within this rank. In 1893, he was described as holding an 'alternate fourth rank' in the imperial nine-rank hierarchy (or jiu pin 九品).[1] Even though Zheng's titles were only ever nominal (hence his alternate rank), they nonetheless enhanced his social stature. Within the statist Confucian social order despite their wealth merchants were traditionally disdained by the ruling elite for being profit-driven people of low moral caliber. Official recognition was thus vitally important to a merchant who had a clear passion for writing on contemporary issues, and for a man who saw himself as a visionary and reformer. Zheng's career as a political publicist began with a series of essays in the early 1870s. By the time Words of Warning appeared in 1893, his ideas on political and social reform and his advocacy of market competition (what he called shang zhan 商戰, literally 'commercial warfare') were already familiar to an urban readership that included officials, merchants and other lettered Chinese. The more progressive among them liked what Zheng wrote. Indeed, much of what appeared in Words of Warning in 1893 would have been known to Zheng's readers for the book was an expanded edition of an earlier work, On Change (Yiyan 易言), a compilation of thirty-six essays that had appeared in 1880 (with an abridged version issued in 1882). Zheng hoped to reach decision-makers at the highest level of government, namely the Qing court and its senior bureaucrats, and by changing the title from On Change to Words of Warning in 1893 he sounded a new urgency of tone and intent.[2] Zheng's desire to counsel the state was greatly aided by Deng Huaxi 鄧華熙 (1826-1917), the progressive governor of Jiangsu, who ensured that Words of Warning reached the highest authority, the Guangxu emperor 光緒 (1871-1908) himself. The emperor read the work in 1895 upon Deng's recommendation. In his 2010 biography of Zheng Guanying, Guo Wu observes that Deng Huaxi's memorial to the emperor of 26 March 1895 included effusive praise for the propositions presented in Words of Warning. Deng even urged the throne to consider a promotion for its author. Meanwhile, the ever-industrious Zheng continued from his base in Shanghai to adapt and finesse his magnum opus for different audiences. Between 1893 and 1900, he produced three subsequent editions of the book with a five-juan (chapter) version appearing in 1894; a fourteen-juan one in 1895 and a revised eight-juan version in 1900.[3]  Fig.1 Zheng Guanying 鄭觀應,< i>Words of Warning to a Prosperous Age (Shengshi weiyan 盛世危言) The work itself makes clear that Zheng's reference to the 'prosperous age' (shengshi 盛世) was heavy in irony, or tinged with ironic hope; the empire was far from prosperous in the 1890s. China's defeat in the 1894 Sino-Japanese War and the signing of the humiliating Treaty of Shimonoseki (Maguan tiaoyue 馬關條約) that followed in 1895 alarmed the concerned public, rousing many to petition and protest against the Qing empire's treatment at the hands of the newly arisen imperialists to the East. Indeed, the prospect of a 'prosperous age' was diming rapidly. By late 1898, following the abortive Hundred Day Reform Movement (Wuxu bianfa 戊戌變法) that led to the Guangxu emperor being held virtually a prisoner to the end of his days, reform-minded writers spoke mostly of the looming dangers of 'China vanishing' (wang guo 亡國). This historical situation stands in stark contrast to present-day uses of the expression 'prosperous age' in Chinese public culture. The fact that Zheng Guanying's book remains a well-known modern classic suggests that in current uses of the term shengshi there is often a tacit acknowledgment of Words of Warning and, in the more considered application of shengshi there is an implicit response to Zheng's forecast. With notable exceptions, however, the publicly acknowledged term shengshi is now mostly bereft of irony and is typically employed to celebrate China's economic wealth and widening global influence [for exceptions see the CIW-Danwei Online Archive: shengshi material in Features]. This semantic loss offers perhaps a cautionary tale of its own. In mainland Chinese discourse today, shengshi has become part of the determinedly cheerful fable of national prosperity under unelected one-party rule. This official narrative effectively reduces China to a single temporality—the 'now' of the Chinese party-state—presented as the crowning moment to which the entire Chinese past had been leading and from which vantage point an always glorious future now beckoned. Hence, it is no accident that writers and wordsmiths keen to publicize their alignment with this self-congratulatory script characteristically complement their use of shengshi with staple phrases in the official discourse such as 'national construction' (jian guo 建國), 'strong nation' (qiangguo 強國), 'reform and opening up' (gaige kaifang 改革開放) and 'social harmony' (shehui hexie 社會和諧).[4] Often, China's flourishing is proclaimed in the titles of such publications. For instance, a lengthy 2008 commemorative article on the thirtieth anniversary of Deng Xiaoping's market reforms bore the title 'Set Your Sights on China's Rise to a Prosperous Age' (Jujiao jueqide shengshi Zhongguo 聚焦崛起的盛世中國).[5] The hyperbole of this article, published in the business magazine China Enterprise is of a piece with official presentations of the nation as a perfect union of the ruler and the ruled. With unintended burlesque, the author explains that it is the interdependence and unity of purpose between the government and the people that has enabled China 'not only to achieve miraculous economic growth and display an arresting splendor but to also become endowed with an unrivalled sense of conviction, heroism and confidence in its own prowess!' While this asserted union has long been a rhetorical staple in the Communist Party's lexicon, the sharpened insistence on economic success is relatively new. Such accolades in effect affirm the legitimacy of one-party rule less in terms of political conviction and leadership and more as good social and economic management. But benign as the idea of 'management' might sound, one-party rule means that repressive force continues to be exercised in ways that show it is fundamental to party primacy. In this regard, crackdowns on dissent have been particularly harsh in 2011. Notwithstanding its steady recourse to coercion and threat, the government has proven unable to silence the real and voluble public outrage that a myriad injustices and inequalities arouse. This outrage is plainly visible on the Internet and in the 'mass incidents' (the official term for street protests and riots) that have occurred in the new century. In this regard, aggrieved Chinese citizens evidently reject the 'harmonious society' that has been the official watchword since the mid-2000s. Despite the government's considerable investment in an Internet police force to control and restrict the flow of information, dissent has flourished in the digital age. (In 2005, China's Internet police was widely reported in the international media as 30,000-strong but its true size today remains a calculated guess). Complaints and criticisms about the present situation come from many different quarters, not least from Communist Party veterans and the offspring of former party leaders and high-ranking cadres. The political pedigree of these dissenting voices has given them privileged media attention both in and outside China, much to the embarrassment of the present leadership in Beijing.[6] It is against this unsettling context of public censure and ridicule of its coercive managerialism that the Chinese government has shown a growing appetite for lavish displays of national grandeur. The 1 October 2009 National Day Parade marking the sixtieth anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic was widely praised in the mainland state-guided media as 'the triumphant ceremony of a prosperous age' (shengshi shengdian 盛世盛典). The message of this spectacle, evocative of parades past but with a focus on the deep pockets of the present administration under Hu Jintao, is that without one-party rule to steer the course of events, prosperity would not have been possible. [See 'Thirteen National Days, a retrospective', China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 17 (March 2009)—The Editor] In intellectual circles, this endorsement of state power as vital for the nation's continued economic success has resulted in a vogue over recent years for what is called 'statism' (guojiazhuyi 國家主義). The theoretical underpinnings of this statist discourse are diverse and cosmopolitan. At one end, they include revisiting the state-Confucianism of the imperial past and the state centralism of the Republican and Maoist eras. At the other end, the ideas of Carl Schmitt and Leo Strauss are valorized for the importance they place on safeguarding national unity.[7] In his robust critique of statism, the eminent historian and public intellectual Xu Jilin 許紀霖 has argued that because it privileges an ideal scenario of responsible governance, statism is constitutively skewed toward legitimizing authoritarian rule. As a consequence, he notes, little consideration is given to protecting individual rights and freedom of speech and association as guaranteed in the Chinese constitution.[8]  Fig.2 Lu Xun The appeal of, and to, an enlightened state in present-day statism takes us back to the 'path of words' (yan lu 言路) that Zheng Guanying offered to the Guangxu emperor in the form of Words of Warning to a Prosperous Age. Zheng lived in a time when powerful bureaucrats played a crucial role in facilitating the passage of reform proposals to the throne. The process, conceived of as the laying down of a 'path of words', was guided by strict protocols that required the loyal subject to present his views as an appeal to the emperor's enlightened sagacity. The situation today is much more complex, with a labyrinth of discursive paths that lead out of university departments, think-tanks and various official and semi-official instrumentalities to the Communist Party's Politburo, enabling academics and officials to collaborate in producing a polished unified view to an increasingly discerning reading public. Zheng Guanying, however, did not envisage the Qing court as being his sole readership. He also actively publicized his views to a rapidly growing urban readership. The numerous editions of Words of Warning that he produced in the 1890s reflects something of his determination to shape public opinion. It is this latter aspect of Zheng's career—his pioneering status as a political publicist—that present-day critics of the status quo recall when commemorating his legacy. Hence, their use of the phrase 'a prosperous age' is distinctly ironic and intended to signal that the appearance of plenty is merely a mirage. Among these critics, the Beijing-based academic Tao Dongfeng 陶東風 issued his 'My Words of Warning for a "Prosperous Age"' (Wode 'shengshi' weiyan 我的'盛世'危言) on the eve of the Lunar New Year in 2009. Tao's essay was of the xiaopin 小品 genre, a reflective personal essay about his mother's recent passing after a prolonged battle with lung cancer. Tao explained that his mother's illness led him to visit his hometown in Zhejiang after an absence of some dozen years. Having placed 'a prosperous age' in scare quotes in the title of his piece, he proceeded to describe with disaffection the spanking new buildings that lined the streets, the disappearance of farming land, rivers and ponds and the foul-smelling air, noting pointedly that there had been a dramatic increase in the local incidence of cancer, and of lung cancer in particular. Of the aberrations he had observed in his hometown, Tao concluded: 'This world that we're living in is speeding toward a terminal destruction.' This gloomy insight is reprised several paragraphs later with the somewhat melodramatic statement: 'These are my words of warning to this prosperous age. The world is being destroyed and humankind is committing suicide.'[9] Here, we should note that Tao addresses 'the world' and 'humankind' even though his warnings are clearly directed at a mainland readership, in particular readers who live in places like his hometown. Like most writers in China today, he chose his words carefully so as to skirt the censors. In Tao's use of the title of Zheng Guanying's book to indict contemporary effusions about a flourishing China we are presented with a rhetorical disposition that is integral to the modern discourse of sixiang 思想. Sixiang is commonly translated as 'Chinese thought' but this transposition fails to convey the idea of 'a concerned mind actively contemplating a problem' that gives the word its dynamism in Chinese. Sixiang comes in many varieties of idiom and vocabulary and is best understood as a discourse that prizes critical independence but does so, in seeming paradox, for the purpose of national improvement. These competing aims of sixiang can be discerned in the frequency of emotional tropes and affective formulations that are intended, ultimately, to convey a heartfelt concern for the common good. The desire to caution and instruct that motivates the production of sixiang is a desire for textual permanence, insofar as sixiang entrusts to itself the mission of evoking the past, guiding the living and providing a beneficial legacy for posterity. Hence, Zheng Guanying intended his use of 'prosperous age' as a vehicle of hope: he appealed to a future age of peace and flourishing, one that he believed that his warnings could help to secure. Here we must note that although Zheng was clearly among the pioneers of modern sixiang, his stature was minor in comparison to such influential luminaries as Tan Sitong 譚嗣同, Yan Fu 嚴復, Kang Youwei 康有為 and Liang Qichao 梁啓超, men who dominated Chinese intellectual discourse in the 1890s and 1900s. In 1925, two decades after Zheng Guanying's Words of Warning was first published, China's best known modern writer, Lu Xun 鲁迅 (1881-1936), wrote acerbically of the many stock phrases in Chinese for extolling prosperity. Producing a different form of sixiang to Zheng Guanying's positive proposals for reform, Lu Xun urged his readers to see that formulations such as 'universal peace' (tianxia taiping 天下太平) and 'the rejoicing multitudes' (wanxing luhuan 萬姓臚歡) were the exact opposite of what they purport. He called them signs of an enduring oppression that confirmed the success of a despotic regime in creating rules for every aspect of life: from 'forced labor and payment of tax grain to ways of kowtowing and praising the sagely ruler'. He wrote that the circumlocutions of scholars disposed to ostentation could be stripped down to reveal two types of longing for: 'the times when we longed to be slaves but couldn't' and 'the times when we succeeded in becoming slaves'. He noted that these desires alternated in accord with the so-called 'cycles of chaos and order' (yizhi yiluan 一治一亂) observed by the early Confucians. In this context, Lu Xun lamented the failure of his intellectual peers to bear witness to the violence of the age. He wrote that they preferred to 'return to the past', to take spiritual refuge in 'the age of peace and prosperity' (taiping shengshi 太平盛世) of some three centuries earlier (that is, at the start of the Manchu-Qing dynasty): 'an age in which [the Chinese] did become securely enslaved for a time.'[10] Lu Xun's profound ambivalence about the mission-driven nature of sixiang led him to cast the work of writing for posterity in negative relief. In 1927, he drew attention to the fact that because he had grown up in the late-nineteenth century amid 'the chaos of the twilight years of the Qing', he was a complete stranger to an 'age of peace and prosperity'. He wrote that the violence he saw around him instilled in him an awareness of the need to exercise 'a good measure of self-restraint' but remarked that this fear of violence proved insufficient to prevent him from 'speaking out every now and then'. He then congratulated himself for 'not knowing my place' and hence encouraged his readers to do likewise, to bear witness to the ills of their time.[11] Instead of the grandeur implicit in shengshi and taiping shengshi, phrases that he disliked and used sardonically, Lu Xun preferred the simple idea of a 'great epoch' (da shidai 大時代). He used this phrase in 1927 to pay homage to the young self-styled revolutionaries of his time who, as he wrote, 'had given their lives for love.' Describing China as fast entering a great epoch, he noted that greatness should be defined not only as a boon to life but death as well. He explained that this was because a great epoch brought things to a head, making the line between life and death unequivocal.[12]  Fig.3 'What is a way? A path that appears where people walk.'—Lu Xun Lu Xun's notion of the 'great epoch' has been reverently recalled in numerous essays of the 2000s to point to the inequities of the status quo. But perhaps the most evocative commemoration of Lu Xun's idea of bearing witness comes not from a mainland intellectual but a latter-day compradore, the Beijing-based Hong Kong writer, publisher and film producer, John Chan Koon-chung (Chen Guanzhong 陳冠中), whose novel, A Prosperous Age: China 2013 盛世, 中国: 2013, attracted immediate attention and critical acclaim upon its publication in late 2009. The book was promptly banned by the mainland authorities. In Linda Jaivin's insightful review of this work commissioned by China Heritage Quarterly, she traces the guiding motif of Chen's novel to a prose poem by Lu Xun 'A Good Hell Lost' quoted midway through the book. The protagonist, Lao Chen, in discussing Lu Xun's poem, is led to ask: 'Given the choice between a good hell and a counterfeit paradise, what will people choose?' Lao Chen answers himself by explaining why most people would choose the latter. As he puts it: Whatever you say, many people will believe that a counterfeit paradise has got to be better than a good hell. Though at first they recognise that the paradise is bogus, they either don't dare or wish to expose it as such. As time passes, they forget that it's not real and actually begin to defend it, insisting that it's the only paradise in existence.[13] In sounding this warning about forgetfulness, Lao Chen's remarks point to the importance of seeing and indicting a counterfeit paradise. These lines, and many others throughout the novel, afforded the author a means to highlight the social ills he perceived, despite the triumphant rhetoric filling the airwaves in China from the mid to late 2000s (when Chan was writing the novel in Beijing). But in Lao Chen's dismissive remarks about the rhetoric of shengshi as signifying nothing more than a bogus paradise, little is said about the type of 'good hell' that Lu Xun depicted. Here we must note that, in Lu Xun's poem, the good hell was a tyranny in which wretched souls were nonetheless allowed to retain a few heart-wrenching memories of their erstwhile humanness. The symbolism of this depiction of a 'good hell' is rich and complex, and ultimately bound up with Lu Xun's view of pre-modern literary Chinese (wenyanwen 文言文) as a vehicle of dynastic tyranny. Lu Xun, a master of wenyanwen, renounced a language he loved in the mid-1910s to promote instead a crudely fashioned modern vernacular (baihuawen 白話文). He championed this modern vernacular as a nation-building tool, but by the 1920s had grown apprehensive of the abundance of revolutionary slogans that baihuawen had accumulated (and enabled). It was during this time that he wrote 'A Good Hell Lost'. In essence Lu Xun depicted the 'good hell' of his poem as a chaotic and oppressive environment in which a sense of human belonging nonetheless continued to flourish. The loss of this 'good hell', he wrote, marked the arrival of a new kind of highly disciplined power—a power that presented itself as human but was hell-bent on achieving its aims and intolerant of anything that stood in its path. As Lu Xun's poem suggests, this was a zeal that could only produce a man-made hell, one so dehumanized that even the devil would be repelled.[14]  Fig.4 Empty Prosperity: 'The New South China Mall is located in Dongguan in China and has been standing empty since 2005. It is 99% vacant because just a very few merchants signed up. The only occupied areas of the mall are near the entrance where several Western fast food chains are located. 'But why is it empty? There are many flaws to the location and the most important is that it's located in the suburbs of Dongguan, where it is practically accessible only by car or bus, so most people don't ever go there. So there you go; No people equals no shopping.' (Source: http://blognator.com/worlds-largest-mall-is-empty/)

Has a 'good hell' been lost in China's present-day rise to prosperity? There is no denying the enormous material benefits that hundreds of millions of Chinese now enjoy as a result of the party-state's zealous pursuit of market reforms since 1978. But against these remarkable achievements, we should also consider the ruthless pace of the post-Maoist modernizing enterprise and the dehumanizing tendencies it has encouraged, particularly in the treatment of the poor and powerless by the rich and powerful. The gargantuan shopping malls and condominium complexes that have now become fixtures in the Chinese landscape offer a salutary example in this regard. Appearing at first glance as concrete proof of China's economic flourishing, these gleaming edifices also bear testament to endemic corruption and collusion between state officers and business investors that have resulted in illegal land seizures, the razing of people's homes, the disruption of lives through forced relocations as well as the loss of life among those who resisted relocation. The fact that many of these buildings remain under-utilized or empty is evocative of the eerie unease that Chan's novel imparts to the idea of China's present 'prosperous age'. What is clear is that despite its currency in mainland public discourse today, shengshi is a fragile idea. It is part of the official lexicon and an assertion of prosperity that remains inaccessible (or formally resistant) to robust debate. Hence, as a term, it remains unexamined, untested and offers little beyond a suggestive symbolism. Indeed, what the rhetorical flourishing of shengshi reveals, more than anything else, is the nervousness of a government that, in failing to make public opinion bend fully to its will has resorted instead to deafening self-congratulation. Related material in this issue of China Heritage Quarterly:

Notes:*My thanks to the Editor of China Heritage Quarterly for his comments on this essay. [1] Zheng Guanying, like many merchants of his day, sought prestige through the acquisition of official titles. Guo Wu notes in his biographical study of Zheng that Zheng purchased his first title in 1869 in the form of a donation: that of a yuanmeilang or second-secretary, the equivalent of an associate fifth rank. He graduated to the langzhong or a full fifth rank the following year. See Guo Wu, Zheng Guanying: Merchant Reformer of late Qing China, Cambria Press, 2010, pp.64-5. [2] Ibid, pp.134-5. [3] Ibid, pp.134-7. [4] The Chinese Internet abounds with such declarations as 'China today is politically progressive, economically prosperous, shows dynamism in foreign policy and enjoys social harmony. This is a flourishing age' (当今中国政治开明,经济繁荣,外交活跃,社会和谐,是一个盛世时代) at Renmin wang qiangguo shequ 人民网强国社区, 8 August 2008, at: http://bbs1.people.com.cn/postDetail.do?view=2&pageNo=1&treeView=1&id=87723503&boardId=1. [5] Cui Caiyuan, 'Jujiao jueqide shengshi Zhongguo', Zhongguo Qiye 中国企业, no.6 (2008), available online, at: http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_61497fbe0100f3zf.html. [6] For instance, see the 11 October 2010 petition signed by twenty-three party veterans including Chairman Mao's former secretary Li Rui and former editor-in-chief of People's Daily, Hu Jiwei, available in English translation at China Media Project, at: http://cmp.hku.hk/2010/10/13/8035/. [7] For a useful summary of the controversy surrounding the advocacy of statism in early 2011, see David Kelly, 'Chinese political transition: a split in the Princeling camp?', East Asia Forum, 21 March 2011, at: http://www.eastasiaforum.org/2011/03/21/chinese-political-transition-split-in-the-princeling-camp/. [8] Xu Jilin, 'Universal civilization or Chinese values? The historicist trend in China of the last decade' (Pushi wenming haishi Zhongguo jiazhi? Jin shinian Zhongguo de lishizhuyi sichao 普世文明还是中国价值?近十年中国的历史主义思潮), Kaifang Shidai 开放时代, no.5 (2010), available online, at: http://www.usc.cuhk.edu.hk/PaperCollection/Details.aspx?id=7909. [9] Tao Dongfeng, 'My words of warning to a "prosperous age", written on the eve of the Lunar New Year' (Danian sanshi: wode 'shengshi' weiyan 大年三十,我的'盛世'危言), 25 January 2009 at: http://blog.ifeng.com/article/2097092.html. [10] Lu Xun, The Collected Works of Lu Xun (Lu Xun Quanji 鲁迅全集, hereafter cited as LXQJ), Beijing: Renmin Wenxue Chubanshe, 1991, vol.1, p.13. [11] LXQJ, 3:81. [12] LXQJ, 3:547. [13] Linda Jaivin, 'Yawning Heights: Chan Koon-chung's Harmonious China', China Heritage Quarterly, No.22 (June 2010) at http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/articles.php?searchterm=022_golden.inc&issue=022. [14] LXQJ, 2:199-201. |