|

FEATURES

New Words of Warning to a Prosperous Age | China Heritage Quarterly

The Children of Yan'an:

New Words of Warning to a Prosperous Age

盛世新危言

Geremie R. Barmé*

[S]aying something well is almost as good as doing something…. If somebody did something they had a right to be somebody, but merely being somebody means nothing if being somebody was the only thing that somebody did.

—Clive James on Celebrity[1]

A Cyclical History

On 4 July 1945, Mao Zedong asked the educator and progressive political activist Huang Yanpei 黄炎培 (1878-1965) what he had made of his visit to the wartime Communist base at Yan'an 延安 in Shaanxi province. In response Huang lauded the collective, hard-working spirit evident among the Communists and their supporters but wondered whether this wartime solidarity could last. He said that the revolutionary ardour of the Communists might wane if they ended up in control of China and pondered whether the political limitations and blemishes of earlier regimes might surface once again, even among the most committed of idealists. Huang said he could see no way out of the 'vicious cycle' of dynastic rise and collapse but expressed the hope that Mao and his followers would be able to break free of history.[2]

Mao declared unequivocally:

We have found a new path; we can break free of the cycle. The path is called democracy. As long as the people have oversight of the government then government will not slacken in its efforts. When everyone takes responsibility there will be no danger that things will return to how they were even if the leader has gone. 我們已經找到了新路,我們能跳出這週期率。這條新路,就是民主。只有讓人民來監督政府,政府才不敢松懈;只有人人起來負責,才不會人亡政息.

Following the 4 June 1989 suppression of a protest movement that had been characterized by inchoate demands for democracy and greater freedoms, Mao's remarks on breaking free of the vicious cycle of the past were dutifully recalled by pro-party mass media historians. As recently as June 2011, the Mao-Huang dialogue featured once more, this time during discussions of China's contemporary politics and its unresolved historical issues.[3]

Fig.1 'Going Among the Masses; Eschewing Empty Talk' ( Shenru qunzhong, bushang kongtan 深入群众,不尚空谈) in Mao Zedong's hand. A modern-day sculpture at the original headquarters of the New China News Agency and Liberation Daily, Qingliang Shan, Yan'an, Shaanxi province

陕西延安清凉山新华社、解放日报社旧址. (Photograph: GRB)

Three months earlier, in February 2011, Mao's declaration that the Communists would lead China away from the tradition of autocracy and the cyclical history of the past was recalled by a group calling itself the Fellowship of the Children of Yan'an when it met in Beijing to celebrate the Lunar New Year. At what has become an annual gathering, the Fellowship canvassed a document in which they called for the implementation of substantive democratic reform within the Communist Party as well as several other major structural changes. They warned that the party-state faced a momentous task, that of realizing the promise of Yan'an.

The Children of Yan'an believed that they were well within their rights to offer their policy advice to the Communist Party, an organization which many of their parents had contributed to building both before and after 1949. For others the outspokenness of the Children of Yan'an was symptomatic of something far more profound: that China had in recent years entered another era of ideological uncertainty, social anomie and open political contestation. It was now common to hear people use a hoary expression when describing the disparate and competing voices of protest: 'it's the end of days; all manner of bizarre characters have been thrown up' (moshi zhengzhao yaonie siqi 末世征兆妖孽四起).

In the context of our discussion of China's Prosperous Age, the advice of the Children of Yan'an, and the views proffered by many other individuals and groups which have spoken up since 2009, recalls a famous book, Words of Warning to a Prosperous Age (Shengshi Weiyan 盛世危言) written by the businessman Zheng Guanying 鄭觀應 (1842-1921) in the dying days of the Qing dynasty over a century ago (for more on Zheng and his work, see Gloria Davies' essay 'Fragile Prosperity' also in the Features section of this issue).

The Children of Yan'an

In April 1984, a group of students who had graduated from elite Beijing middle schools created an informal association to celebrate their camaraderie and their origins. They called themselves the Fellowship of the Children of New China (Xinhua Ernü Lianyihui 新华儿女联谊会).[4] At the time of the centenary of Mao Zedong's birth in 1993, the group renamed itself the Beijing Children of Yan'an Classmates Fellowship (Beijing Yan'an Ernü Xiaoyou Lianyihui 北京延安儿女校友联谊会). Its members were the descendants of men and women who had lived and worked in the Yan'an Communist Base in Shaanxi province from the 1930s to the 1940s, as well as the progeny of the party who were born and educated in Yan'an. From 1998, the group held annual gatherings to coincide with Spring Festival (Chinese New Year), as well as a range of other events organized around choral and dancing groups, Taijiquan classes, and painting and calligraphy activities. In 2001, they shortened their name to the Beijing Children of Yan'an Fellowship.

Since 2002, the group has been led by Hu Muying 胡木英, daughter of Hu Qiaomu 胡乔木, a party wordsmith par excellence and Mao Zedong's one-time secretary (Deng Xiaoping called him 'The First Pen of the Communist Party' Qiaomu shi women dangnei de diyi zhi bi 乔木是我们党内的第一支笔杆).[5] In 2008, the fellowship expanded its membership to include those without any specific link to the old Communist base and its revolutionary éclat. Henceforth, the Children of Yan'an would include any individual who wanted to work under the banner of the organization, collaborate with it and support its vision which was stated as being 'to inherit the revolutionary tradition, glorify the Yan'an spirit, build camaraderie with the children of the revolution, sing the praises of the national ethos and to work in various capacities for the old revolutionary areas, ethnic regions, the nation's frontiers and impoverished areas.'[6]

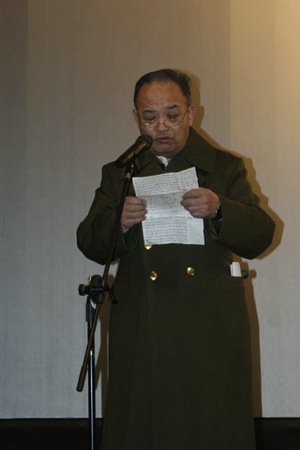

Fig.2 Hu Muying 胡木英, 13 February 2011: 胡木英会长2月13日在延安儿女联谊会团拜大会上致词

Spring Festival 2011

With a core membership of some one hundred people, the Children of Yan'an Fellowship not only boasted the leadership of Hu Muying, but also the key participation of Li Min 李敏 (Mao Zedong's older daughter), Zhou Bingde 周秉德 (Zhou Enlai's niece), Ren Yuanfang 任远芳 (party elder Ren Bishi's 任弼时 daughter), Lu Jianjian 陆健健 (former party propaganda chief Lu Dingyi's 陆定一 son) and Chen Haosu 陈昊苏 (son of Chen Yi 陈毅, the pre-Cultural Revolution party-state Mayor of Shanghai and later Minister of Foreign Affairs). On 13 February 2011, the group held their annual Chinese New Year gathering in the auditorium of the 1 August Film Studio, an organization under the direct aegis of the People's Liberation Army.

On that occasion, apart from the Children of Yan'an, a range of other interested groups, or what were dubbed 'revolutionary mass organisations' (geming qunzhong tuanti 革命群众团体) were also present.[7] During the speech-ifying that day these various attendees were collectively represented by Chen Haosu, himself a former film and TV bureaucrat with a noble party lineage that we have noted above. The Children of Yan'an Fellowship itself was represented by Hu Muying and her deputy, Zhang Ya'nan 张亚南, formerly the Political Commissar of the PLA Logistics Department and previously secretary to Wei Guoqing 韦国清, a Cultural Revolution-era Vice-chairman of the National People's Congress.

Following a series of platitudinous remarks and a brief recounting of the long years of struggle that their revolutionary forebears had gone through to found New China (an account that, not surprisingly, glossed over the bloody horrors of the first three decades of party rule from 1949 to 1978), Hu Muying said:

The new explorations made possible by Reform and the Open Door policies have, over the past three decades, resulted in remarkable economic results. At the same time, ideological confusion has reigned and the country has been awash in intellectual currents that negate Mao Zedong Thought and Socialism. Corruption and the disparity between the wealthy and the poor are of increasingly serious concern; latent social contradictions are becoming more extreme.

We are absolutely not 'Princelings' (Taizi Dang 太子党), nor are we 'Second-generation Bureaucrats' (Guan Erdai 官二代). We are the Red Successors, the Revolutionary Progeny, and as such we cannot but be concerned about the fate of our Party, our Nation and our People. We can no longer ignore the present crisis of the Party.[8]

Hu went on to say that through the activities of study groups, lecture series and symposia the Children of Yan'an had formulated a document that, following broad-based consultation, would be presented to Party Central. The document is entitled 'Our Suggestions for the Eighteenth Party Congress' (Women dui Shiba Dade jianyi 我们对十八大的建议).[9] 'We cannot', Hu continued:

…be satisfied merely with reminiscences nor can we wallow in nostalgia for the glories of the sufferings of our parent's generation. We must carry on in their heroic spirit, contemplate and forge ahead by asking ever-new questions that respond to the new situations with which we are confronted. We must attempt to address these questions and contribute to the healthy growth of our Party and help prevent our People once more from eating the bitterness of the capitalist past.

The speech concluded with assurances that the group was working with similar organizations to mark the 1 July 2011 ninetieth anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party with various activities ranging from discussions and symposia to arts performances and exhibitions. She assured her audience that they would pursue their agenda into the future.

Fig.2 Zhang Ya'nan 张亚南, 13 February 2011: 张亚南副会长2月13日在延安儿女联谊会春节团拜会致词

For his part, Zhang Ya'nan declared that China's Communist Party, the Communist cause and Marxism-Leninism itself were being directly challenged and indeed disparaged by the enemies of the revolutionary founding fathers. In particular, he despaired at the de-Maoification that continued to unfold in China. He reminded his audience that 'Chairman Mao bequeathed us four things: one piece of software and three pieces of hardware. The hardware is the Chinese Communist Party, the Chinese People's Liberation Army and the People's Republic of China. The software is Mao Zedong Thought.' Zhang went on to praise the Red Culture campaign launched by Bo Xilai 薄熙来 in Chongqing in 2008, the work of Luo Yuan 罗援 and the writings of Zhang Tieshan 张铁山. He then commended to his audience the document formulated for the party's upcoming Eighteenth Congress. He declared that it was a manifesto that gave voice to their wish 'to love the party, protect the flag and to revitalize the as-yet-unfinished enterprise of the revolutionary fathers' (aidang hu qi zhenxing laoyibei gemingjia weijing shiye 爱党护旗振兴老一辈革命家未竟事业). He also suggested that the Children of Yan'an should invite activists who were involved in the Mao Zedong Banner website (毛泽东旗帜网) and the Workers' Website (工人网) to their next Spring Festival gathering in January 2012.[10]

Advising the Eighteenth Party Congress

The document drafted by the Children of Yan'an for consideration by the party in the lead up to the 2012 Eighteenth Party Congress, and the changeover of leaders expected at the time, calls for:

1. Direct elections of twenty percent of party representatives, including the membership of the party's Central Committee and the Central Disciplinary Commission;

2. Representation in the Politburo;

3. An increase in the authority of the Central Disciplinary Commission so that it becomes as powerful as Party Central itself;

4. Reform of the Central Disciplinary Commission;

5. Establishment of a new Central Policy Committee (Zhongyang Zhengce Weiyuanhui 中央政策委员会) of equivalent stature and authority as the party's Central Committee and its Central Disciplinary Commission. The role of the new committee would be to 'safeguard continuity in party building and in overseeing the management of a peaceful nation'. It would ensure that the party's policies were truly reflective of the popular will (minyi 民意) and it would better enable the party to correct its deviations and errors (piancha he shiwu 偏差和失误). Its membership would be drawn democratically from all levels of the party structure; and,

6. Open elections to the National People's Congress and the National People's Consultative Congress to the popular vote.[11]

The document then details how these various recommendations could best be implemented. The text is remarkable in a number of ways. Being framed at a juncture between two recent triumphs (the 2008 Beijing Olympic Year and the 2010 Shanghai World Expo) and the imminent and politically momentous 2012 Party Congress, it states a clear intention to revive the legacy of the revolutionary past: in effect its authors were calling for the recognition of a left-wing faction within the Communist Party itself (more on this below). Fascinating too is that, while the party has expended considerable energy on silencing or sidelining liberal thought in contemporary China, as well as containing demands from dissenting thinkers who favour western-style democratic reform, those inside the party who still claim some remnant leftist heritage are actively agitating for practicable party reform and for a kind of internal Communist Party 'democratization'. One might venture that few observers would find this particular version of populist democracy within an autocratic one-party schemata to be particularly attractive.

Also noteworthy, if not unsettling, is the fact that among the key speeches and documents produced by the Children of Yan'an there appears to be little cognizance of China's burgeoning global influence, its enmeshment with the international economic order or awareness of regional concerns about the country's rapid military build-up and the impact of its intermittent bellicosity. Meanwhile, with their gaze fixed more on the past than the present, the drafters of 'Our Suggestions for the Eighteenth Party Congress' reaffirmed the primacy of what is known as the 'mass line' (qunzhong luxian 群众路线). First articulated as early as 1929, the mass line is regarded as one of the foundations of Mao Zedong Thought. It calls for the party to rely unwaveringly on the masses (a vague and ill-defined group at the best of times), to put faith in them, arouse them, go among them, honestly learn from them and serve them.

Fig.3 Chen Haosu 陈昊苏, 13 February 2011

The Children of Yan'an declared that their reform proposals were a practical realization of the long-standing principle of the mass line, one that was enshrined in the party's Constitution and which had in the past ensured the party's successes (sic). Moreover, they declared that party leaders cannot afford any longer to use social and political stability as an excuse for further delaying substantive reforms to China's political system. The Children of Yan'an declare that new political talent could be found among the masses, in particular among the enthusiastic party faithful. They claimed, for instance, that the Red Song Movement (chang hongge 唱红歌) that originated in Chongqing and which later spread nationwide, had seen the appearance of just the kind of enthusiastic younger party stalwarts who would help ensure the continuation of the Communist enterprise long into the future. In the 1960s, Mao Zedong had warned that after his demise people would inevitably 'use the red flag to oppose the red flag' (da hongqi fan hongqi 打红旗反红旗). Now it would appear that the Children of Yan'an were using their very ownred flag to oppose the red flag of economic reform that, since 1978, had been employed to oppose the red flag of Maoism.

The revival of a faux-Maoist 'Red Culture' in Chongqing under Bo Xilai, as well as in Xi'an (Shaanxi province) would soon be affirmed (or was it really to be co-opted and marginalized?) by party leaders, in particular by Politburo Standing Committee member and head of the party-state legal establishment Zhou Yongkang 周永康. Around the time that Bo Xilai led a delegation of 'red songsters' to Beijing in mid June 2011, Zhou called for the 'forging of three million idealistic and disciplined souls who are ready to face all dangers with an unwavering faith' (yingjie fengxian, jianding xinnian, zhuzao sanbaiwan you lixiang jiang jilüde linghun 迎接风险,坚定信念,铸造三百万有理想讲纪律的灵魂). Of importance in the crucible of the engineers of human souls (linghunde gongchengshi 灵魂的工程师) was what would now be called the 'Five Reds', that is, 'Reading red books, studying red history, singing red songs, watching red movies and taking the red path' (du hongshu, kan hong shi, chang hongge, kan hong pian, zou honglu 读红书、看红史、唱红歌、看红片、走红路). The feints between Party Central and Chongqing continued and, on 30 June, when Bo Xilai officiated over a 100,000-person strong 'Red Song Rally' in Chongqing to celebrate the 1 July ninetieth anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party, it was announced that a formal letter of congratulation and support dated 22 June had been sent to the organisers of the rally by Li Changchun 李长春, the Politburo member with oversight of ideology and culture.[12]

The Children of Yan'an concluded their February 2011 plea for party reform by referring back to Mao Zedong's July 1945 exchange with Huang Yanpei in Yan'an. They reminded their readers of Mao's belief that the party had identified the final solution to China's historical trap:

We have found a new path; we can break free of the cycle. The path is called democracy. As long as the people have oversight of the government then government will not slacken in its efforts.

In no uncertain terms the Children of Yan'an now declared:

We are calling on the whole party to take a substantive step in this direction (huyu quandang shishi zaizai maichu zhe yi bu 呼吁全党实实在在迈出这一步).[13]

Not only had the Children of Yan'an formulated a manifesto and begun agitating for political reform before the looming change of party leadership. It was said that in their pursuit of a Maoist-style 'mass line' they had engendered tentative contacts with grass-roots organizations and petitioner groups in and outside Beijing. For left-leaning figures in contemporary China to engage in such practical, and non-hierarchical, politics was highly significant, especially when considered against the rise of China's 'New Left' (Xin zuopai 新左派) in the 1990s and 2000s as an academic and literary coterie well-versed in Euro-American styles of theorizing.

The 'New Left' intellectuals are variously celebrated and derided for talking up a storm (both in China and at the various international academic fora to which they are frequently invited) about 'recuperating' radical socio-political agendas, the post-capitalist turn in China and how best to utilize the 'resources' of Marxism-Maoism in the context of the reform-era. They had, quite literally, become 'paper generals' (zhishang tan bing 紙上談兵) whose rhetorical enemy were liberal thinkers and ideas. To their critics, what such 'leftists' seemed to 'recuperate' most deftly was the late-Qing tradition of idle speculation, or 'clear talk' (qingyi 清議). Few had demonstrated any practicable awareness of or desire to deal with the deprived, marginalized, dispossessed or repressed individuals in the society as a whole. While elite members of this leftist claque formed meaty alliances with their global intellectual coevals, on the ground in China protest, resistance and opposition to the oppressive practices of party-capitalism has remained the province of lone activists, NGO groups, liberal intellectuals, lawyers and the woefully 'under-theorised'.

The reticence of the 'New Left' is, however, understandable. Apart from the usual intellectual qualms about direct social engagement among those who are more comfortable dealing with academic jousting and refereed publications in prestigious journals, in China principled activism exacts a high price. After all, the engaged intellectual soon confronts a policed authoritarian environment that is infamously punitive. Moreover, the fate of such prominent nay-sayers as Liu Xiaobo and Ai Weiwei would deter all but the most foolhardy. More disturbing yet is the cruel abuse of numerous (and often nameless) men and women of conscience who have been harried, detained and persecuted by local power-holders and business interests for often the most spurious reasons.

Other Words of Warning

Since the last major public power struggle within the Chinese Communist Party over two decades ago, it has become an accepted view of China's particular brand of one-party consensual authoritarianism that prior to any leadership change jostling for position within the hierarchy takes a number of forms. While it is all but impossible to track effectively the backroom dealings, the power plays and the political feints involved in this byzantine process, the media still provides some indication of the nature of inner party tussles. Zhongnanhai-ology, however, remains at best an imaginative art.

Nonetheless, given the volubility of various critics since 2009, not to mention the unseemly activities of the Children of Yan'an, as well as the pointed remarks about contemporary Chinese politics by figures such as Liu Yuan 刘源 (the former president of the People's Republic Liu Shaoqi's 刘少奇 son),[14] by early 2011 observers were wondering what had happened to the usually outspoken organs of Party Central.

In late May 2011, the party did indeed make itself heard over the din of fraught contestation. In an opinion piece published by the Central Disciplinary Commission on 25 May, party members were warned to obey 'political discipline' and to cease henceforth from offering unsolicited and wayward views on China's political future. It declared that shutting down idle speculation was part of a 'profound political struggle' (yichang yansude zhengzhi douzheng 一场严肃的政治斗争) that confronted the party. The article went on to re-iterate Party General Secretary Hu Jintao's 'Six Absolutely Verbotens' (liuge jue bu yunxu 六个决不允许) for party members—basically, follow the party line and do not engage in public discussions or offer personal opinions; do not fabricate or spread political gossip; and, do not leak state secrets or participate in illegal organisations.[15]

The document noted that there were those who were 'pursuing their own agendas in regard to party policy and requirements, all the while making a show of being in step with the party; others have been taken in by various stories they pick up, indulge in idle speculation and generate "political rumours".' Furthermore, it warned that dissenting party voices were leading to (disruptive) non-party and international speculation about the Communist Party's leadership and its future. In other words, it could damage the national economy.

Fellowships and Factions

In 1044CE, the Song-dynasty political figure and writer Ouyang Xiu 歐陽修 submitted a memorial to the throne entitled 'On Factions' (Pengdang lun 朋黨論). In it he argued against the long-standing taboo on coalitions in government. He suggested to the throne that political groupings of like-minded men working for the benefit of the court and its dynastic subjects were in fact a constructive development. Regarded as the most famous argument in favour of political alliances in Chinese history, 'On Factions' has resonated through the ages.

In his memorial Ouyang said:

Thus, Your servant claims that petty men are without factions and that only superior men have them. Why is this so? Official salaries and gain are what petty men enjoy; wealth and goods are what petty men covet. When they seek mutual gain, they will temporarily form an affiliation (dang), but it is erroneous to consider them to be a faction (peng). When they glimpse gain and contend to be first [to take it], or when the gains have been exhausted, and they squabble over what remains, then they will cruelly injure each other. Even if they are brothers or kinsmen, they will not be able to protect each other.

然臣謂小人無朋,惟君子有之。其故何哉?小人所好者利祿也,所貪者財貨也;當其同利時,暫相黨引以為朋者,偽也。及其見利而爭先,或利盡而交疏,則反相賊害,雖其兄弟親戚,不能相保。故臣謂小人無朋,其暫為朋者,偽也。

…this is not so for superior men. The Way and righteousness are what they defend; loyalty and sincerity are what they practice; and reputation and integrity are what they value. Since they have cultivated themselves, their common Way (tongdao) is of mutual benefit. Since they serve the polity, their common hearts help each other, and they are always as one. Such are the affiliations of superior men.

君子則不然。所守者道義,所形者忠義,所惜者名節;以之修身,則同道而相益,以之事國,則同心而共濟,終始如一。此君子之朋也。[16]

Mao Zedong was notorious for construing those with political differences as being members of dangerous factions and alliances. He frequently warned against the dangers of 'cliques' (zongpai 宗派); he demonized his perceived rivals as pursuing a political line invidious to the Chinese revolution and he was merciless first in toying with those whom he suspected of having formed alliances in opposition to him and then in obliterating them. Differences in policy, strategy and even personality were depicted as 'line struggles' (luxian douzheng 路线斗争) and, for decades, the history of modern China as accounted by the Communist Party was a record of such struggles.

When discussing political differences Mao Zedong did, in his lighter moments, quote a famous 1927 poem by the early party leader Chen Duxiu 陳獨秀. Known as the 'Four-character Classic on the Nationalist Party' (Guomindang sizijing 国民党四字经), the poem was written following the KMT-Communist split. In light of China's contemporary political ructions in this the Xinhai centenary year, it is instructive (even if intelligible only to those familiar with the fraught and ultimately doomed 'united front' politics of the 1920s):

黨外無黨,帝王思想; 黨內無派,千奇百怪。

以黨治國,放屁胡說; 黨化教育,專制余毒。

三民主義,胡說道地; 五權憲法,夾七夾八。

建國大綱,官樣文章; 清黨反共,革命送終。

軍政時期,軍閥得意; 訓政時期,官僚運氣;

憲政時期,遙遙無期。 忠誠黨員,只要洋錢;

恭讀遺囑,阿彌陀佛。

The lines '訓政時期,官僚運氣;憲政時期,遙遙無期' (Under the party's political tutelage, the bureaucrats strike it rich;/Constitutional government, that's for a far distant future) appear as grimly humorous today as they were over eighty years ago.

In the landscape of authoritarian Chinese politics there has occasionally been an attempt to recognize, if not formalize, the role of a 'loyal opposition' in government. In the history of the Chinese Communist Party, which celebrates the ninetieth anniversary of its founding on 1 July 2011, inner party factions were outlawed, often in the most violent manner. Although the Chinese Communist Party may well maintain that China in the twenty-first century is led by one party in coalition with other 'democratic parties' (minzhu dangpai 民主党派) that contribute to the political process, the reality is that no quarter is given to formal oppositionist politics.

The historian F.W. Mote offered the following observation on Ouyang Xiu's Song-dynasty memorial and the problems that it highlighted for future generations. Mote's comment is relevant to a discussion of political contestation under the one-party state in China even today:

The failure of Neo-Confucian thinkers and political activists to break through this formal barrier against concerted political action by groups of like-minded men, by disallowing any distinction between good and bad factions, severely limited Chinese political behavior thereafter, up to the end of the imperial era in the early twentieth century… The attempt to redefine 'factions' would arise again and again, up to the eighteenth century, but the state's definition always prevailed. Legitimate political parties could not take form, and any who expressed political disagreements were, by definition, morally defective, hence insidious. 'Loyal opposition' could not be acknowledged within a system of politics defined by ethical and personal rather than by operational and institutional norms. China still struggles with the heritage of this eleventh-century political failure.[17]

For those alert to the echoes of China's past in its still-autocratic present, Ouyang Xiu's 1000-year-old memorial has an eerie resonance. 'On Factions' remains widely read and referred to. Perhaps not as frequently read is the Chinese Communist Party's own interdictions on factional activities. In somewhat less sonorous language than that of Ouyang Xiu, Chapter 1 of the Party Constitution, Article 3, Points 4 & 5 stipulate that party members are required:

To conscientiously observe party discipline, abide by the laws and regulations of the state in an exemplary way, rigorously guard secrets of the party and state, execute the party's decisions, and accept any job and actively fulfill any task assigned them by the party.

To uphold the party's solidarity and unity, be loyal to and honest with the party, match words with deeds, firmly oppose all factions and small-clique activities and oppose double-dealing and scheming of any kind.

党员义务:党员要'自觉遵守党的纪律,模范遵守国家的法律法规,严格保守党和国家的秘密,执行党的决定,服从组织分配,积极完成党的任务'.

党员有义务'维护党的团结和统一,对党忠诚老实,言行一致,坚决反对一切派别组织和小集团活动,反对阳奉阴违的两面派行为和一切阴谋诡计'.[18]

The Yan'an Way

'Political tutelage' (xun zheng 訓政) as referred to in Chen Duxiu's poem is an expression that dates from the early Chinese Republic. In the 1920s, the Nationalist Party leader Sun Yat-sen had argued that a period of military rule could help ensure the creation of a united modern China. Thereafter, he believed, a period of political tutelage would be necessary to maintain stability until constitutional rule and democracy could eventually be realized (this paradigm is summed up in Chinese as jun zheng, xun zheng, xian zheng 軍政>訓政>憲政).

In the discussion of China's Harmonious Prosperous Age in this issue of China Heritage Quarterly, it has been relevant to introduce and discuss the contested legacy of the country's revolutionary tradition. We have also argued that earlier periods in Chinese history provide a vital backdrop to contemporary discussions of the country's future.

Fig.4 'Beginning of the Great Revival' ( Jiandang weiye 建党伟业), a film released in the build up to the party-state's 24/7 celebration of its ninetieth birthday on 1 July 2011

From as early as the late-Kangxi period of the High Qing—the last decades of the seventeenth century—the throne expressed anxiety about the decline of the martial virtues of the ruler caste, the Manchu bannermen, the 'people of the banners' (Man. gûsai niyalma; Chi. qiren 旗人). The 'old ways' (fe doro in Manchu) that had brought the Manchus and in particular the Aisin Gioro clan to power seemed even then to be slipping away; the formerly stalwart warriors succumbing bit by bit to the easy life and manners of Beijing and its corrupting 'Chinese lifestyle' (Nikan-i doro). As time passed, and what had been a virile rule normalized into institutional and domestic comfort, the canker spread. As Mark Elliott has noted in his magisterial work on the Qing:

…appeals for the revitalization of the Manchu Way, like any typical call to preserve the (frequently imaginary) ideals of a past golden age, went largely unheeded for the simple reason that the cultural practices it encouraged and glorified were becoming less meaningful to more people. Yet they would never lose their significance altogether, remaining as memories: the brave grandfather who died in battle, the bow on the wall, and the Manchu books there on the shelf, no longer read.[19]

The political nostalgia of today's Children of Yan'an may well be regarded in a similar light: the descendants of a military caste that vaunted its 'hardy and frugal' (jianku pusu 艰苦朴素) workstyle have, despite their righteous protestations, long since succumbed to the ease and comforts afforded by entitlement and prosperity. It may seem easy to dismiss the Yan'an revanchists but we must not forget that the world of ideas, the language and some of the practices that they evoke still occupy a crucial part of China's political mainstream. It is a world that should not be ignored, and it is one that it would be unwise to deny. In terms of practical politics and the volatile social environment of the People's Republic it is hard to tell whether the revivalist Red Culture or what is still derisively dubbed 'red fundamentalism' (hong yuan jiaozhizhuyi 红原教旨主义) occupy anything more than a quaint market niche in the ideological landscape.[20]

In his day Mao Zedong was famously (or was it 'neurotically') concerned with backsliding, revisionism and the slackening of revolutionary ardour. Through mass movements and purges he hoped to create a mechanism whereby China could maintain its transformative zeal into the future. But he knew the lessons of history too well. In 1945, before gaining national power, Mao had told Huang Yanpei that through democracy the Communists would be able to break free forever from the vicious cycle of dynastic rise and fall. Although Huang died before the Cultural Revolution broke out, he lived long enough into the People's Republic to see the lie behind Mao's claims. For his part, the later Mao had little confidence in the Communist Party maintaining its revolutionary raison d'être. In his autumn years he would quote a famous line from the pre-Qin philosopher Mencius 孟子 that summed up what even then seemed like an inescapable denouement: 'The influence of a sovereign sage terminates in the fifth generation' (junzi zhi ze wu shi er zhan 君子之澤五世而斬).[21]

In 2012, the fifth generation of party leaders will be inaugurated at the Eighteenth Congress of the Chinese Communist Party. The man set up to succeed Hu Jintao as Party General Secretary is Xi Jinping 习近平, the son of General Xi Zhongxun 习仲勋 and a bona fide child of Yan'an.

Related material from China Heritage Quarterly:

Notes:

* My thanks to Gloria Davies for her suggested last-minute refinements of this text.

[1] Clive James, 'Save Us From Celebrity' (2004), collected in his The Meaning of Recognition, New Essays 2001-2005, London: Picador, 2005, p.350.

[2] Huang's remarks are recorded as follows:

我生六十多年,耳聞的不說,所親眼看到的,真所謂'其興也勃焉,其亡也忽焉'。一人、一家、一團體、一地方乃至一國,不少單位都沒能跳出這週期率的支配力。大凡初時聚精會神,沒有一事不用心,沒有一人不賣力,也許那時艱難困苦,只有從萬死中覓取一生。繼而環境漸漸好轉了,精神也漸漸放下了。有的因為歷時長久,自然地惰性發作,由少數演為多數,到風氣養成,雖有大力,無法扭轉,並且無法補救。也有因為區域一步步擴大了,它的擴大,有的出於自然發展;有的為功業欲所驅使,強求發展,到幹部人才漸漸竭蹶,艱於應付的時候,有環境倒越加複雜起來了,控制力不免薄弱了。一部歷史,'政怠宦成'的也有,'人亡政息'的也有,'求榮取辱'的也有。總之,沒有能跳出這個週期率。中共諸君從過去到現在,我略略瞭解的,就是希望找出一條新路,來跳出這個週期率的支配。

[3] For details, see the Chinese transcript of the 6 June 2011 symposium 'China Needs a New Political Culture' (Zhongguo xuyao xinde zhengzhi wenming 中国需要新的政治文明), online at: http://zyzg.us/thread-223235-1-1.html.

[4] This overview is based on the Children of Yan'an website. See: http://www.yananernv.cn/geren.html.

[5] See: http://roll.sohu.com/20110602/n309175600.shtml. In May 2011, there were both official and unofficial denials that Hu Qiaomu co-authored, or even wrote, some of the key works in the Maoist canon (including the 'Three Old Pieces' Lao San Pian 老三篇: Serve the People, On Contradiction and On Practice, as well as Mao's most famous poem, 'Snow—to the tune of Qinyuan Chun (Xue, Qinyuan Chun 雪,沁園春). For details, see: http://www.sdenews.com/html/2011/5/110415.htm, and; http://www.wyzxsx.com/Article/Class14/201105/237163.html. Nonetheless, the rumours persist. I recall well in the early 1990s hearing talk from well-placed sources in Beijing that Hu had claimed copyright (and royalties) for certain contributions to the corpus of Mao's writings when he was visited by Politburo members during his final illness. But then again, Mao Thought has long been redefined as the 'crystallisation of the collective genius of the Party'. Presumably everyone, therefore, can claim a stake in the oeuvre.

[6] 延安儿女愿意在这个旗帜下一起联谊、合作。我们的宗旨是:'继承革命传统,弘扬延安精神,联谊革命后代的情谊,讴歌民族正气,为老少边穷地区做些力所能及的工作。'

[7] These groups included: 新四军研究会、井冈儿女联谊会、十一同学会、红岩儿女联谊会、西花厅联谊会、北京八路军山东抗日根据地研究会、太岳精神传承会、抗联儿女联谊会、冀中研究会、西路军儿女联谊会筹备组、开国元勋合唱团、北京十一同学会、101中同学会、育才同学会、八一同学会、华北小学同学会、育英学校同学会. All of these groups boast complex backgrounds, affiliations and party-state-army connections.

[8] For Hu's speech, see: '胡木英会长2月13日在延安儿女联谊会团拜大会上的致词', online at: http://www.yananernv.cn/news_2425.html.

[9] For details, see: http://www.yananernv.cn/news_2427.html.

[10] For Zhang Ya'nan's speech, see '春节团拜会主持词(摘录)', online at: http://www.yananernv.cn/news_2428.html. The 'de-Maoification' referred to by Zhang was actually a formal process launched by the Chinese Communist Party in the late 1970s. In recent years, however, more detailed critiques of Mao and his period of rule have been published by those with less sympathy for the Communist cause. The most recent of these appeared in April 2011, some two months after Zhang Ya'nan's handwringing. It was written by the academic Mao Yushi 茅于轼: 'Return Mao Zedong to Humanity—on reading The Sun Also Falls' (Ba Mao Zedong huanyuan cheng ren—du Hongtaiyangde yunluo 把毛泽东还原成人——读〈红太阳的陨落〉), online at: http://china.dwnews.com/news/2011-04-26/57658778.html.

[11] This is only a crude summary of the proposals contained in the document. For the original, see: '我们对十八大的建议(8稿)——延安儿女联谊会学习中心座谈会发言材料之一 ', online at: http://www.yananernv.cn/news_2423.html.

[12] For the Chongqing Daily online report, see '(重庆) 中华红歌会隆重开幕' at:

http://news.online.cq.cn/chongqing/2011/06/30/3350893.html. For those interested in another form of Real Politik it is perhaps also noteworthy that the 'old friend of China', Henry Kissinger, attended the rally.

[13] '我们对十八大的建议(8稿)——延安儿女联谊会学习中心座谈会发言材料之一 ', online at: http://www.yananernv.cn/news_2423.html.

[14] On Liu, see http://www.smh.com.au/business/chinas-party-princelings-fight-for-a-chance-to-go-back-to-the-future-20110523-1f0pu.html#ixzz1NBu6Brqn. For Liu Yuan's rambling discussion of the need for a new (even more bellicose) historical perspective in China, see his 'Why Should We Transform Our Culturo-historical Weltanschauung?—on reading Zhang Musheng' (Wei shenme yao gaizai womende wenhua lishi guan?—du Zhang Musheng 为什么要改造我们的文化历史观——读张木生, 3 August 2010), online at: http://theory.people.com.cn/GB/12328780.html.

[15] See 中纪闻:坚决维护党的政治纪律 Online at: http://opinion.people.com.cn/GB/14727703.html ; and the independent commentary at: http://www.chinese.rfi.fr/中国/20110525-中纪委警告中共党员莫对重大政治问题"说三道四". Among other things, the notification warned that:

极少数党员、干部在一些涉及党的基本理论、基本路线、基本纲领、基本经验的重大政治问题上说三道四、我行我素;有的对中央的决策和要求阳奉阴违、另搞一套;还有的不负责任地道听途说,甚至捕风捉影,编造传播政治谣言,丑化党和国家形象,在干部、群众中造成恶劣影响。这些都是党的政治纪律所不容许的。

[16] From Ari Daniel Levine, Divided by a Common Language: Factional Conflict in Late Northern Song China, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2008, pp.49-50. My thanks to Gloria Davies for bringing this recent translation to my attention. For a somewhat different version of Ouyang's essay, and a lengthy discussion, see also James T.C. Liu, Ou-yang Hsiu: An Eleventh-Century Neo-Confucianist, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1967, pp.53ff. The full text of Ouyang Xiu's 'On Factions' is as follows:

臣聞朋黨之說,自古有之,惟幸人君辨其君子小人而已。大凡君子與君子,以同道為朋 ;小人與小人,以同利為朋;此自然之理也。

然臣謂小人無朋,惟君子有之。其故何哉?小人所好者利祿也,所貪者財貨也;當其同利時,暫相黨引以為朋者,偽也。及其見利而爭先,或利盡而交疏,則反相賊害,雖其兄弟親戚,不能相保。故臣謂小人無朋,其暫為朋者,偽也。君子則不然。所守者道義,所形者忠義,所惜者名節;以之修身,則同道而相益,以之事國,則同心而共濟,終始如一。此君子之朋也。故為人君者,但當退小人之偽朋,用君子之真朋,則天下治矣。 堯之時,小人共工、驩兜等四人為一朋, 君子八元、八愷十六人為一朋。舜佐堯,退四 凶小人之朋,而進元、愷君子之朋,堯之天下大治。及舜自為天子,而皋、夔、稷、契等二 十二人,並立於朝,更相稱美,更相推讓,凡二十二人為一朋;而舜皆用之,天下亦大治。《書》曰:「紂有臣億萬,惟億萬心;周有臣三千,惟一心。 」紂之時,億萬人各異心,可謂不為朋矣,然紂以亡國。周武王之臣三千人為一大朋,而周用以興。 後漢獻帝時,盡取天下名士囚禁之,目為黨人;及黃巾賊起,漢室大亂,後方悔悟,盡解黨人而釋之,然已無救矣。唐之晚年, 漸起朋黨之論。及昭宗時,盡殺朝之名士,咸投之黃河,曰:「此輩清流, 可投濁流。」而唐遂亡矣。

夫前世之主,能使人人異心不為朋,莫如紂;能禁絕善人為朋,莫如漢獻帝;能誅戮清流之朋,莫如唐昭宗後世;然皆亂亡其國。更相稱美、推讓而不自疑, 莫如舜之二十二臣;舜亦不疑而皆用之。然而後世不誚舜為二十二朋黨所欺,而稱舜為聰明之聖者,以能辨君子與小人也。周武之世, 舉其國之臣三千人共為一朋。自古為朋之多且大莫如周,然周用此以 興者,善人雖多而不厭也。 嗟乎!治亂興亡之跡,為人君者可以鑒矣。

[17] F.W. Mote, Imperial China 900-1800, Cambridge, Ma.: Harvard University Press, 1999, p.137.

[18] From 'The Constitution of the Communist Party of China', online at: http://www.china.org.cn/english/congress/229722.htm.

[19] Mark C. Elliott, The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001, p.304.

[20] Some scholars have identified even in the Reform-era practices of the Communist Party powerful links to Mao-era practices. See Sebastian Heilmann, Elizabeth Perry, eds, Mao's Invisible Hand: The Political Foundations of Adaptive Government in China, Cambridge, Ma.: Harvard University Asia Center, 2011.

[21] From 孟子·離婁章句下. The English translation is by James Legge. Following a recent, rather candid, speech to the faithful, the Communist Party Secretary of Shanghai, Yu Zhensheng 俞正声, was asked what he thought the future held for the party. He responded:

It depends on the party itself, not only any single individual. If our party can remain committed and overcome its own faults it will have a bright future. If, however, the party proves to be weak and ineffectual, there will be no hope for it.

党的未来取决于党本身,而不是取决于他人。我们党本身如果能够坚强,能够克服自身的弊端,未来是光明的;如果党本身软弱无力,这个党就是没有希望的。

|